Code of Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is There a Role for Proof of Character, Propensity, Or Prior Bad Conduct in Medical Negligence Litigation?, 63 S.C

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2011 Good Medicine/Bad Medicine And The Law Of Evidence: Is There A Role For Proof Of Character, Propensity, Or Prior Bad Conduct In Medical Negligence Litigation?, 63 S.C. L. Rev. 367 (2011) Marc Ginsberg The John Marshall Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Evidence Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, Litigation Commons, Medical Jurisprudence Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Marc Ginsberg, Good Medicine/Bad Medicine And The Law Of Evidence: Is There A Role For Proof Of Character, Propensity, Or Prior Bad Conduct In Medical Negligence Litigation?, 63 S.C. L. Rev. 367 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/352 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOOD MEDICINE/BAD MEDICINE AND THE LAW OF EVIDENCE: Is THERE A ROLE FOR PROOF OF CHARACTER, PROPENSITY, OR PRIOR BAD CONDUCT IN MEDICAL NEGLIGENCE LITIGATION? Marc D. Ginsberg* I. IN TRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 368 II. RULES OF EVIDENCE INVOLVED .................................................................. 370 111. PHYSICIAN REPUTATION ............................................................................. 373 IV. PRIOR LAWSUITS AGAINST THE PHYSICIAN DEFENDANT ........................... 378 V. EVIDENCE OF PHYSICIAN TREATMENT OF OTHER PATIENTS- IN AD M ISSIB LE ............................................................................................. 380 VI. EVIDENCE OF PHYSICIAN TREATMENT OF OTHER PATIENTS- A D M ISSIB LE ............................................................................................... -

The Applicability of the Character Evidence Rule to Corporations

KIM.DOC 12/20/00 2:32 PM CHARACTERISTICS OF SOULLESS PERSONS: THE APPLICABILITY OF THE CHARACTER EVIDENCE RULE TO CORPORATIONS ∗ Susanna M. Kim Under Federal Rule of Evidence 404, the character evidence rule, it is well established that evidence of character generally is not admissible to show that a person acted in conformity with that char- acter on a particular occasion. No consensus exists, however, as to whether the character evidence rule should also apply to corpora- tions. In this article, Professor Kim argues that the ban on character evidence should not be extended to corporations. Professor Kim be- gins with a discussion of various rationales offered to support the character evidence rule, emphasizing Kantian conceptions of human autonomy. She then examines varying definitions of “character” and concludes that character may best be regarded as a reflection of the internal operating system of the human organism. Next, Professor Kim turns to an analysis of the personhood of corporations and de- termines that corporations are persons and moral actors with the ca- pacity to possess character. This corporate character is separate and apart from the character of the corporation’s individual members and reflects the internal operating system of the corporate organization. Finally, Professor Kim suggests that the human autonomy ra- tionale for the character evidence rule does not apply with equal force to corporations. She then concludes with an examination of the prac- tical implications of excluding corporations from the protections af- forded individuals under Rule 404. To a seemingly ever-increasing extent the members of society, individual and corporate alike, are awash in an existential sea, out ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Chapman University School of Law. -

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the Means, Sanctioned by These

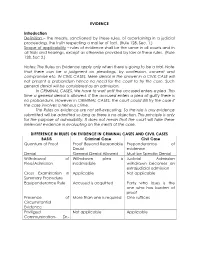

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the means, sanctioned by these rules, of ascertaining in a judicial proceeding, the truth respecting a matter of fact. (Rule 128, Sec. 1.) Scope of applicability – rules of evidence shall be the same in all courts and in all trials and hearings, except as otherwise provided by law or these rules. (Rule 128, Sec 2.) Notes: The Rules on Evidence apply only when there is going to be a trial. Note that there can be a judgment on pleadings, by confession, consent and compromise etc. IN CIVIL CASES. Mere denial in the answer in a CIVIL CASE will not present a probandum hence no need for the court to try the case. Such general denial will be considered as an admission. In CRIMINAL CASES, We have to wait until the accused enters a plea. This time a general denial is allowed. If the accused enters a plea of guilty there is no probandum. However in CRIMINAL CASES, the court could still try the case if the case involves a heinous crime. The Rules on evidence are not self-executing. So the rule is any evidence submitted will be admitted so long as there is no objection. This principle is only for the purpose of admissibility. It does not mean that the court will take these irrelevant evidence in evaluating on the merits of the case. DIFFERENCE IN RULES ON EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL CASES AND CIVIL CASES BASIS Criminal Case Civil Case Quantum of Proof Proof Beyond Reasonable Preponderance of Doubt evidence Denial General Denial Allowed Must be Specific Denial Withdrawal of Withdrawn plea is Judicial Admission Plea/Admission -

An Introduction to the Rules of Evidence Applicable to Collection Cases in Maryland Trial Courts Lynn Mclain University of Baltimore, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 7-30-2002 An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts Lynn McLain University of Baltimore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Evidence Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Lynn McLain, An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts, (2002). Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/916 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RULES OF EVIDENCE ApPLICABLE TO COLLECTION CASES IN MARYLAND TRIAL COURTS Prof. Lynn McLain University of Baltimore School of Law July 30, 2002 ~ PROFESSOR LYNN McLAIN ~ University of Baltimore School of Law John and Frances Angelos Law Center 1420 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21201-5779 Professor McLain (J.D., 1974, with distinction, Duke University School of Law), was an associate at Piper & Marbury, a graduate fellow at Duke, and then in 1977 joined the faculty at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where she is the Dean Joseph Curtis Faculty Fellow and teaches courses in evidence and copyright law. Prof. McLain is admitted to the bars of the Maryland Court of Appeals (December 1974), the United States District Court for the District of Maryland (March 1975), and the United States Supreme Court (March 1990). -

"Ancient Documents" As Evidence

The Archivist and "Ancient Documents" as Evidence Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/26/4/487/2744520/aarc_26_4_148255750366p7l6.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 By CYRUS B. KING* D. H. Hill Library N. C. State of the University of North Carolina at Raleigh GENERATION or more after the occurrence of a certain event, when all of the witnesses have passed from the scene, A litigation stemming from that event normally must proceed on the basis of documents created contemporaneously with the event. As the custodian of needed documents, an archivist may very well find himself embroiled in litigation that requires the use of evidentiary documents in his care. The archivist's involve- ment ordinarily results from the question of custody, one of the several conditions affecting the admissibility of a document as evidence in a court of law under the common-law ancient documents rule. For some three centuries judges have accepted the validity of the common-law rule that an ancient document, under certain con- ditions, may be taken as sufficiently genuine to be submitted to a jury as evidence without further authentication of its genuineness.1 The reason for such a rule, of course, is the impossibility of ob- taining living testimony to prove that the document is indeed gen- uine. Until a certain lapse of time, after which all of the living witnesses are gone, there is no necessity for the application of the rule. From such necessity evolved the common-law ancient documents rule. At first the requirement -

Evidence: Admissibility of Newspapers Under the Hearsay Rule

EVIDENCE: ADMISSIBILITY OF NEWSPAPERS UNDER THE HEARSAY RULE NEWSPAPERS OFFERED in evidence as proof of the facts recited therein are out-of-court declarations generally held to be inadmissible under the hearsay rule.' However, in a recent decision, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that an exception to this exclusionary rule will be made where the evidence in question is necessary and the circumstances under which the declaration was made provide guarantees of trust- worthiness. In Dallas County v. Commercial Union Assur. Co.,2 a county in Alabama, following the collapse of its courthouse on July 7, 1957, sought to recover on a lightning insurance policy, contending that the collapse was caused by lightning which had struck the courthouse on July 2. The plaintiff attributed char in the debris to lightning. Deny- ing liability, the defendant caimed that lightning had not struck the courthouse and that the collapse was caused by structural weaknesses.8 To explain the presence of char, the defendant introduced expert testi- mony indicating a fire at some earlier date and offered in evidence a June 9, 19O1, copy of the local newspaper, which contained an anony- mous article reporting a fire in the then unfinished tower.4 The federal district judge admitted the document as "part of the records"5 of the newspaper company over the plaintiff's objection that this was hearsay evidence. On appeal from judgment on a jury verdict for the defendant, the plaintiff assigned as error the admission of the newspaper into evidence. 'Watford v. Evening Star Newspaper Co., zxi F.zd 31 (D.C. -

2016-05-07 Evidence Rules Report to the Standing Committee

COMMITTEE ON RULES OF PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE OF THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON, D.C. 20544 JEFFREY S. SUTTON CHAIRS OF ADVISORY COMMITTEES CHAIR STEVEN M. COLLOTON REBECCA A. WOMELDORF APPELLATE RULES SECRETARY SANDRA SEGAL IKUTA BANKRUPTCY RULES JOHN D. BATES CIVIL RULES DONALD W. MOLLOY CRIMINAL RULES WILLIAM K. SESSIONS III EVIDENCE RULES MEMORANDUM TO: Hon. Jeffrey S. Sutton, Chair Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure FROM: Hon. William K. Sessions, III, Chair Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules RE: Report of the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules DATE: May 7, 2016 ______________________________________________________________________________ I. Introduction The Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules (the “Committee”) met on April 29, 2016 in Alexandria, Virginia. The Committee seeks final approval of two proposed amendments for submission to the Judicial Conference: 1. Amendment to Rule 803(16), the ancient documents exception to the hearsay rule, to limit its application to documents prepared before 1998; and 2. Amendment to Rule 902 to add two subdivisions that would allow authentication of certain electronic evidence by way of certification by a qualified person. The Committee also seeks approval of a Manual on best practices for authenticating electronic evidence, to be published by the Federal Judicial Center. June 6-7, 2016 Page 45 of 772 Report to the Standing Committee Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules May 7, 2016 Page 2 II. Action Items A. Amendment Limiting the Coverage of Rule 803(16) Rule 803(16) provides a hearsay exception for “ancient documents.” If a document is more than 20 years old and appears authentic, it is admissible for the truth of its contents. -

Appendix a ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1

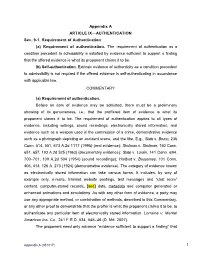

Appendix A ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1. Requirement of Authentication (a) Requirement of authentication. The requirement of authentication as a condition precedent to admissibility is satisfied by evidence sufficient to support a finding that the offered evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. (b) Self-authentication. Extrinsic evidence of authenticity as a condition precedent to admissibility is not required if the offered evidence is self-authenticating in accordance with applicable law. COMMENTARY (a) Requirement of authentication. Before an item of evidence may be admitted, there must be a preliminary showing of its genuineness, i.e., that the proffered item of evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. The requirement of authentication applies to all types of evidence, including writings, sound recordings, electronically stored information, real evidence such as a weapon used in the commission of a crime, demonstrative evidence such as a photograph depicting an accident scene, and the like. E.g., State v. Bruno, 236 Conn. 514, 551, 673 A.2d 1117 (1996) (real evidence); Shulman v. Shulman, 150 Conn. 651, 657, 193 A.2d 525 (1963) (documentary evidence); State v. Lorain, 141 Conn. 694, 700–701, 109 A.2d 504 (1954) (sound recordings); Hurlburt v. Bussemey, 101 Conn. 406, 414, 126 A. 273 (1924) (demonstrative evidence). The category of evidence known as electronically stored information can take various forms. It includes, by way of example only, e-mails, Internet website postings, text messages and “chat room” content, computer-stored records, [and] data, metadata and computer generated or enhanced animations and simulations. As with any other form of evidence, a party may use any appropriate method, or combination of methods, described in this Commentary, or any other proof to demonstrate that the proffer is what the proponent claims it to be, to authenticate any particular item of electronically stored information. -

Download Barkai's Hawaii Rules of Evidence

HAWAII RULES OF EVIDENCE HANDBOOK 2018 Professor John Barkai William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawaii The Hawaii Rules of Evidence were last amended in 2011 i HAWAII RULES OF EVIDENCE HANDBOOK 2018 Professor John Barkai William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawaii Honolulu, HI 96822 ISBN: 978-1-948027-00-7 Regarding copyright - there is none. Of course, there is no claim to copyright the Hawaii Rules of Evidence, which are government works. In addition, your may freely copy and use other sections of this handbook, primarily the appendices, under a Creative Commons Attribution (CCBY) 4.0 License, which essentially means that you may use, share, or adapt the information in the appendices for any purpose, even commercial, if you give "appropriate credit" and indicate changes you made, if any. You cannot restrict others from using these materials. The suggested attribution is to cite the material as: John Barkai, Hawaii Rules of Evidence Handbook (2018). No legal advice. The author and publisher are offering no legal advice. The law is whatever the judge in your case says the law is. Formatting. There seems to be no standard formatting style for presenting the Hawaii Rules of Evidence or the Federal Rules of Evidence. This handbook uses formatting generally consistent with the formatting used for these rules in Hawaii Revised Statutes, but with some paragraph modifications intended to make the understanding and application of the rules as clear as possible - but clarity and understanding of the rules of evidence by using the text alone is almost impossible. -

Ancient Documents and the Rule Against Multiple Hearsay Gregg Kettles

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 39 | Number 3 Article 2 1-1-1999 Ancient Documents and the Rule Against Multiple Hearsay Gregg Kettles Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gregg Kettles, Ancient Documents and the Rule Against Multiple Hearsay, 39 Santa Clara L. Rev. 719 (1999). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol39/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANCIENT DOCUMENTS AND THE RULE AGAINST MULTIPLE HEARSAY Gregg Kettles* I. INTRODUCTION This article analyzes whether statements in a document properly authenticated as "ancient" pursuant to Federal Rule of Evidence 901(b)(8) are subject to the rule against multiple hearsay. I conclude that the rule against multiple hearsay applies to such statements in ancient documents. In order for a given statement in an ancient document to be admissi- ble to prove the truth of the matter asserted, the statement must either be within the personal knowledge of the author or qualify under a separate exception to the hearsay rule. For each level of hearsay present within the document, the party offering the hearsay evidence must demonstrate that an exception to the hearsay rule applies. Federal Rule of Evidence 802 provides that "[h]earsay' is not admissible except as provided by these rules or by other rules prescribed by the Supreme Court pursuant to statutory authority or by Act of Congress."2 Rule 803 sets out a num- ber of exceptions to this rule, including the following: "(16) [s]tatements in ancient documents" and "[s]tatements in a document in existence twenty years or more the authenticity of which is established."3 Authenticating a document as "an- cient" is accomplished by satisfying the straightforward * The author received his J.D. -

CHARACTER EVIDENCE QUICK REFERENCE Reputation – Opinion – Specific Instances of Conduct - Habit

CHARACTER EVIDENCE QUICK REFERENCE reputation – opinion – specific instances of conduct - habit Character of the Defendant – 404(a)(1) (pages 14-29) (pages 4-8) * Test: Proper Purpose + Relevance + Time * Test: Relevance (to the crime charged) + Similarity + 403 balancing; rule of inclusion + 403 balancing; rule of exclusion * Put basis for ruling in record (including * Defendant gets to go first w/ "good 403 balancing analysis) character" evidence – reputation or opinion only (see rule 405) * D has burden to keep 404(b) evidence out ^ State can cross-examine as to specific instances of bad character * proper purposes: motive, opportunity, knowledge/intent, preparation/m.o., common * Law-abidingness ALWAYS relevant scheme/plan, identity, absence of mistake/ accident/entrapment, res gestae (anything * General good character not relevant but propensity) * Defendant's character is substantive ^ Credibility is never proper – 608(b), not 404(b) evidence of innocence – entitled to instruction if requested * time: remoteness is less significant when used to show intent, motive, m.o., * D's evidence of self-defense does not knowledge, or lack of mistake/accident - automatically put character at issue * remoteness more significant when common scheme or plan (seven year rule) ^ unless continuous course of conduct, or D is gone * similarity: particularized, but not Character of the victim – 404(a)(2) (pages 8-11) necessarily bizarre ^ the more similar acts are, the less problematic time is * Test: Relevance (to the crime charged) + 403 balancing; -

Habit Forming: Evidence of Physician Habit in Medical Negligence Litigation

Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 2 Habit Forming: Evidence of Physician Habit in Medical Negligence Litigation Marc D. Ginsberg B.A., M.A., J.D., LL.M. (Health Law), Professor, UIC John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjhple Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Marc D. Ginsberg, Habit Forming: Evidence of Physician Habit in Medical Negligence Litigation, 19 YALE J. HEALTH POL'Y L. & ETHICS (). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjhple/vol19/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics by an authorized editor of Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ginsberg: Habit Forming: Evidence of Physician Habit in Medical Negligence Habit Forming: Evidence of Physician Habit in Medical Negligence Litigation Marc D. Ginsberg* Abstract: ”Habit” is a time-honored component of the law of evidence. Habit evidence is generally understood as specific conduct which occurs repetitively, over a period of time, in response to a known stimulus. Habitual conduct is also thought to be non-volitional, suggesting that it encompasses conduct without thought. This paper focuses on whether the practice of medicine is, in any respect, “habitual.” Are