8.03 ADMISSION by a PARTY 8.05 ADMISSION by ADOPTED STATEMENT 8.07 ANCIENT DOCUMENTS 8.09 COCONSPIRATOR STATEMENT 8.11 DECLARATION V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits of Punishment Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism

i n s t i t u t e f o r i n t e g r at e d t r a n s i t i o n s The Limits of Punishment Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism May, 2018 United Nations University – Centre for Policy Research The UNU Centre for Policy Research (UNU-CPR) is a UN-focused think tank based at UNU Centre in Tokyo. UNU-CPR’s mission is to generate policy research that informs major UN policy processes in the fields of peace and security, humanitarian affairs, and global development. i n s t i t u t e f o r i n t e g r at e d t r a n s i t i o n s Institute for Integrated Transitions IFIT’s aim is to help fragile and conflict-affected states achieve more sustainable transitions out of war or authoritarianism by serving as an independent expert resource for locally-led efforts to improve political, economic, social and security conditions. IFIT seeks to transform current practice away from fragmented interventions and toward more integrated solutions that strengthen peace, democracy and human rights in countries attempting to break cycles of conflict or repression. Cover image nigeria. 2017. Maiduguri. After being screened for association with Boko Haram and held in military custody, this child was released into a transit center and the care of the government and Unicef. © Paolo Pellegrin/Magnum Photos. This material has been supported by UK aid from the UK government; the views expressed are those of the authors. -

Federal Rules of Evidence: 801-03, 901

FEDERAL RULES OF EVIDENCE: 801-03, 901 Rule 801. Definitions The following definitions apply under this article: (a) Statement. A "statement" is (1) an oral or written assertion or (2) nonverbal conduct of a person, if it is intended by the person as an assertion. (b) Declarant. A "declarant" is a person who makes a statement. (c) Hearsay. "Hearsay" is a statement, other than one made by the declarant while testifying at the trial or hearing, offered in evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted. (d) Statements which are not hearsay. A statement is not hearsay if-- (1) Prior statement by witness. The declarant testifies at the trial or hearing and is subject to cross- examination concerning the statement, and the statement is (A) inconsistent with the declarant's testimony, and was given under oath subject to the penalty of perjury at a trial, hearing, or other proceeding, or in a deposition, or (B) consistent with the declarant's testimony and is offered to rebut an express or implied charge against the declarant of recent fabrication or improper influence or motive, or (C) one of identification of a person made after perceiving the person; or (2) Admission by party-opponent. The statement is offered against a party and is (A) the party's own statement, in either an individual or a representative capacity or (B) a statement of which the party has manifested an adoption or belief in its truth, or (C) a statement by a person authorized by the party to make a statement concerning the subject, or (D) a statement by the party's agent or servant concerning a matter within the scope of the agency or employment, made during the existence of the relationship, or (E) a statement by a coconspirator of a party during the course and in furtherance of the conspiracy. -

Conditional Relevance and the Admissibility of Party Admissions Gerald F

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2007 Conditional Relevance and the Admissibility of Party Admissions Gerald F. Uelmen Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Recommended Citation 36 Sw. U. L. Rev. 657 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONDITIONAL RELEVANCE AND THE ADMISSIBILITY OF PARTY ADMISSIONS Gerald F. Uelmen* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 657 II. THE ALLOCATION OF RESPONSIBILITY FOR FINDING PRELIMINARY FACTS UNDER THE CALIFORNIA EVIDENCE C O D E ....................................................................................... 6 5 8 III. THE ALLOCATION OF RESPONSIBILITY FOR FINDING PRELIMINARY FACTS IN FEDERAL COURTS PRIOR TO B O URJA ILY .............................................................................. 66 1 IV. THE BOURJAILY DECISION AND ITS AFTERMATH ................... 664 V. POST-BOURJAILY CONFUSION IN THE FEDERAL COURT ........ 669 VI. WHAT DIFFERENCE DOES IT MAKE? ................. .. .. .. .. 672 I. INTRODUCTION Among the most significant differences between the Federal Rules of Evidence and the California Evidence Code is the allocation between -

Medical Hearsay Issue Sheet

COMPILED BY: AEQUITAS: THE PROSECUTORS’ RESOURCE ON VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN Medical Hearsay Issue Sheet I. ROLE OF THE SANE/SAFE NURSE A. National Definition of a SANE/SAFE: The 2004 National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations define SAFEs as, “health care professionals who conduct the examination.” SANEs are defined as “registered nurses who received specialized education and fulfill clinical requirement required to perform these exams. Additionally, SAFE and SANEs “are often used to more broadly denote a health care provider who has been specially educated and completed clinical requirement to perform the exam.” B. How do SANE/SAFE’s define themselves: The definition of the SANE/SAFE is crucial to the determination of the primary purpose of the sexual assault exam. The definition of the SANE/SAFE role will vary by jurisdiction and it must be clear that the SANE/SAFE is not a branch of law enforcement but an independent medical professional who has a two pronged responsibility to the community: (1) to provide access to comprehensive immediate care; and (2) also to facilitate investigations. The national protocol emphasizes a “coordinated community response,” focusing on “victim centered care.”1 II. CRAWFORD OBJECTIONS A. What is a Crawford Objection? Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36 (2004) held that statements by witnesses that are testimonial are barred under the confrontation clause, unless witnesses are available and defendant had prior opportunity to cross examine, regardless of reliability. In determining whether testimony is admissible under Crawford/Davis, first ask yourself two questions; (1) Is the statement testimonial? And (2) What was the primary purpose for obtaining a statement? 1 National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations, U.S. -

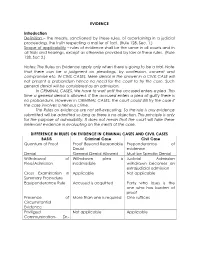

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the Means, Sanctioned by These

EVIDENCE Introduction Definition – the means, sanctioned by these rules, of ascertaining in a judicial proceeding, the truth respecting a matter of fact. (Rule 128, Sec. 1.) Scope of applicability – rules of evidence shall be the same in all courts and in all trials and hearings, except as otherwise provided by law or these rules. (Rule 128, Sec 2.) Notes: The Rules on Evidence apply only when there is going to be a trial. Note that there can be a judgment on pleadings, by confession, consent and compromise etc. IN CIVIL CASES. Mere denial in the answer in a CIVIL CASE will not present a probandum hence no need for the court to try the case. Such general denial will be considered as an admission. In CRIMINAL CASES, We have to wait until the accused enters a plea. This time a general denial is allowed. If the accused enters a plea of guilty there is no probandum. However in CRIMINAL CASES, the court could still try the case if the case involves a heinous crime. The Rules on evidence are not self-executing. So the rule is any evidence submitted will be admitted so long as there is no objection. This principle is only for the purpose of admissibility. It does not mean that the court will take these irrelevant evidence in evaluating on the merits of the case. DIFFERENCE IN RULES ON EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL CASES AND CIVIL CASES BASIS Criminal Case Civil Case Quantum of Proof Proof Beyond Reasonable Preponderance of Doubt evidence Denial General Denial Allowed Must be Specific Denial Withdrawal of Withdrawn plea is Judicial Admission Plea/Admission -

An Introduction to the Rules of Evidence Applicable to Collection Cases in Maryland Trial Courts Lynn Mclain University of Baltimore, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 7-30-2002 An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts Lynn McLain University of Baltimore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Evidence Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Lynn McLain, An Introduction To The Rules Of Evidence Applicable To Collection Cases In Maryland Trial Courts, (2002). Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/916 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RULES OF EVIDENCE ApPLICABLE TO COLLECTION CASES IN MARYLAND TRIAL COURTS Prof. Lynn McLain University of Baltimore School of Law July 30, 2002 ~ PROFESSOR LYNN McLAIN ~ University of Baltimore School of Law John and Frances Angelos Law Center 1420 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21201-5779 Professor McLain (J.D., 1974, with distinction, Duke University School of Law), was an associate at Piper & Marbury, a graduate fellow at Duke, and then in 1977 joined the faculty at the University of Baltimore School of Law, where she is the Dean Joseph Curtis Faculty Fellow and teaches courses in evidence and copyright law. Prof. McLain is admitted to the bars of the Maryland Court of Appeals (December 1974), the United States District Court for the District of Maryland (March 1975), and the United States Supreme Court (March 1990). -

"Ancient Documents" As Evidence

The Archivist and "Ancient Documents" as Evidence Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/26/4/487/2744520/aarc_26_4_148255750366p7l6.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 By CYRUS B. KING* D. H. Hill Library N. C. State of the University of North Carolina at Raleigh GENERATION or more after the occurrence of a certain event, when all of the witnesses have passed from the scene, A litigation stemming from that event normally must proceed on the basis of documents created contemporaneously with the event. As the custodian of needed documents, an archivist may very well find himself embroiled in litigation that requires the use of evidentiary documents in his care. The archivist's involve- ment ordinarily results from the question of custody, one of the several conditions affecting the admissibility of a document as evidence in a court of law under the common-law ancient documents rule. For some three centuries judges have accepted the validity of the common-law rule that an ancient document, under certain con- ditions, may be taken as sufficiently genuine to be submitted to a jury as evidence without further authentication of its genuineness.1 The reason for such a rule, of course, is the impossibility of ob- taining living testimony to prove that the document is indeed gen- uine. Until a certain lapse of time, after which all of the living witnesses are gone, there is no necessity for the application of the rule. From such necessity evolved the common-law ancient documents rule. At first the requirement -

The Admission of Government Agency Reports Under Federal Rule of Evidence 803(8)(C) by John D

The Admission of Government Agency Reports under Federal Rule of Evidence 803(8)(c) By John D. Winter and Adam P. Blumenkrantz or (B) matters observed pursuant having hearsay evidence admitted under to duty imposed by law as to which Rule 803(8)(c) follow from the justifica- matters there was a duty to report, tions for adopting the rule in the first excluding, however, in criminal cases place. The hearsay exception is premised matters observed by police officers on several conditions. First, the rule as- and other law enforcement person- sumes that government employees will nel, or (C) in civil actions . factual carry out their official duties in an honest 2 John D. Winter Adam P. Blumenkrantz findings resulting from an investiga- and thorough manner. This assump- tion made pursuant to authority tion results in the rule’s presumption of n product liability and other tort ac- granted by law, unless the sources of reliability. Second, the rule is based on the tions, plaintiffs may seek to introduce information or other circumstances government’s ability to investigate and re- Igovernment records or documents, indicate lack of trustworthiness. port on complex issues raised in many cas- federal and nonfederal alike, to establish es, from product liability claims to section one or more elements of their claims. In This article focuses specifically on 1983 actions against government officials. this regard, plaintiffs attempt to rely on the third prong of the rule: the use of Government agencies generally possess reports or letters written by government agency records in civil actions that result levels of expertise, resources, and experi- agencies responsible for overseeing the from an agency investigation made ence, including access to information that health, safety, and consumer aspects pursuant to authority granted by law. -

11-3-2012-06-26.Pdf

PUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. No. 11-3 CHADRICK EVAN FULKS, Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of South Carolina, at Florence. Joseph F. Anderson, Jr., District Judge. (4:02-cr-00992-JFA-1; 4:08-cv-70072-JFA) Argued: March 20, 2012 Decided: June 26, 2012 Before WILKINSON, KING, and AGEE, Circuit Judges. Affirmed by published opinion. Judge King wrote the opin- ion, in which Judge Wilkinson and Judge Agee joined. COUNSEL ARGUED: Billy Horatio Nolas, Amy Gershenfeld Donnella, FEDERAL COMMUNITY DEFENDER OFFICE, Philadel- phia, Pennsylvania, for Appellant. Thomas Ernest Booth, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, Washing- ton, D.C., for Appellee. ON BRIEF: William N. Nettles, 2 UNITED STATES v. FULKS United States Attorney, Robert F. Daley, Jr., Assistant United States Attorney, OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY, Columbia, South Carolina; Lanny A. Breuer, Assistant Attorney General, Greg D. Andres, Acting Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Scott N. Schools, Associate Dep- uty Attorney General, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, Washington, D.C., for Appellee. OPINION KING, Circuit Judge: Having pleaded guilty in the District of South Carolina to all eight counts of a superseding indictment, Chadrick Evan Fulks was, on the recommendation of a jury, sentenced to the death penalty. The capital sentence was imposed on Fulks’s convictions of Counts One and Two of the superseding indict- ment, respectively, carjacking resulting in death, in contraven- tion of 18 U.S.C. § 2119(3), and kidnapping resulting in death, as proscribed by 18 U.S.C. -

Evidence: Admissibility of Newspapers Under the Hearsay Rule

EVIDENCE: ADMISSIBILITY OF NEWSPAPERS UNDER THE HEARSAY RULE NEWSPAPERS OFFERED in evidence as proof of the facts recited therein are out-of-court declarations generally held to be inadmissible under the hearsay rule.' However, in a recent decision, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that an exception to this exclusionary rule will be made where the evidence in question is necessary and the circumstances under which the declaration was made provide guarantees of trust- worthiness. In Dallas County v. Commercial Union Assur. Co.,2 a county in Alabama, following the collapse of its courthouse on July 7, 1957, sought to recover on a lightning insurance policy, contending that the collapse was caused by lightning which had struck the courthouse on July 2. The plaintiff attributed char in the debris to lightning. Deny- ing liability, the defendant caimed that lightning had not struck the courthouse and that the collapse was caused by structural weaknesses.8 To explain the presence of char, the defendant introduced expert testi- mony indicating a fire at some earlier date and offered in evidence a June 9, 19O1, copy of the local newspaper, which contained an anony- mous article reporting a fire in the then unfinished tower.4 The federal district judge admitted the document as "part of the records"5 of the newspaper company over the plaintiff's objection that this was hearsay evidence. On appeal from judgment on a jury verdict for the defendant, the plaintiff assigned as error the admission of the newspaper into evidence. 'Watford v. Evening Star Newspaper Co., zxi F.zd 31 (D.C. -

Case 3:10-Cv-02642-L Document 49 Filed 10/07/11 Page 1 of 24 Pageid

Case 3:10-cv-02642-L Document 49 Filed 10/07/11 Page 1 of 24 PageID <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION ADONAI COMMUNICATIONS, LTD., § § Plaintiff, § § v. § Civil Action No. 3:10-CV-2642-L § AWSTIN INVESTMENTS, LLC, et. al., § § Defendants. § MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Pursuant to the order of reference dated June 3, 2011, before the Court for determination is Defendants’ Objections to and Motion to Strike the Affidavit Testimony of Bill Podsednik and Documents Attached Thereto, filed May 27, 2011 (doc. 31). Based on the relevant filings and applicable law, the motion is GRANTED, in part, and DENIED, in part. I. BACKGROUND This action arises out of an alleged breach of a share-purchase agreement allegedly requiring payment of certain deferred taxes and indemnification of millions of dollars in tax liability. Adonai Communications, Ltd. (Plaintiff) has filed this lawsuit against Michael Bernstein; Awstin Investments, L.L.C.; Premium Acquisitions, Inc. formerly known as MidCoast Acquisitions Corp.; Premium Investors, Inc. formerly known as MidCoast Investments, Inc.; MDC Credit Corp. formerly known as MidCoast Credit Corp.; Shorewood Associates, Inc.; and Shorewood Holdings Corp. It asserts claims for breach of contract, common law fraud, statutory fraud, fraud by non- disclosure, and negligent misrepresentation, and seeks indemnification and a judicial declaration of its rights and duties under the agreement. Plaintiff claims that a labyrinth of these entities, led by Bernstein, systematically defrauded it by promising to indemnify it and pay outstanding tax Case 3:10-cv-02642-L Document 49 Filed 10/07/11 Page 2 of 24 PageID <pageID> obligations as part of the stock-purchase agreement with absolutely no intention of fulfilling that promise. -

Meta-Evidence and Preliminary Injunctions

UC Irvine Law Review Volume 10 Issue 4 Article 9 6-2020 Meta-Evidence and Preliminary Injunctions Maggie Wittlin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr Part of the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation Maggie Wittlin, Meta-Evidence and Preliminary Injunctions, 10 U.C. IRVINE L. REV. 1331 (2020). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol10/iss4/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Law Review by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. First to Printer_Wittlin.docx (Do Not Delete) 6/5/20 9:09 PM Meta-Evidence and Preliminary Injunctions Maggie Wittlin The decision to issue a preliminary injunction is enormously consequential; it has been likened to “judgment and execution before trial.” Yet, courts regularly say that our primary tool for promoting truth seeking at trial—the Federal Rules of Evidence—does not apply at preliminary injunction hearings. Judges frequently consider inadmissible evidence to make what may be the most important ruling in the case. This Article critically examines this widespread evidentiary practice. In critiquing courts’ justifications for abandoning the Rules in the preliminary injunction context, this Article introduces a new concept: “meta-evidence.” Meta-evidence is evidence of what evidence will be presented at trial. I demonstrate that much evidence introduced at the preliminary injunction stage is, in fact, meta-evidence. And I show why meta-evidence that initially appears inadmissible under the Rules is often, in fact, admissible. Applying the Rules at the preliminary injunction stage, then, would not exclude nearly as much evidence as courts may have assumed.