Private Solutions for Infrastructure in Lesotho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Household Population and Housing Characteristics 2

HOUSEHOLD POPULATION AND HOUSING CHARACTERISTICS 2 John Nkonyana This chapter presents information on the social, economic, and demographic characteristics of the household population, focusing mainly on such background characteristics as age, sex, educational attendance and attainment, place of residence, and socioeconomic conditions of households. The information provided is intended to facilitate interpretation of the key demographic, socioeconomic, and health indices. It is further intended to assist in the assessment of the representativeness of the survey. One of the background characteristics used throughout this report is an index of socioeconomic status. The economic index used here was recently developed and tested in a large number of countries in relation to inequities in household income, use of health services, and health outcomes (Rutstein et al., 2000). It is an indicator of the level of wealth that is consistent with expenditure and income measures (Rutstein, 1999). The economic index was constructed using household asset data with principal components analysis. The asset information was collected through the Household Questionnaire of the 2004 LDHS and covers information on household ownership of a number of consumer items ranging from a television to a bicycle or car, as well as dwelling characteristics, such as source of drinking water, sanitation facilities, and type of material used for flooring. Each asset was assigned a weight (factor score) generated through principal components analysis, and the resulting asset scores were standardized in relation to a normal distribution with a mean of zero and standard deviation of one (Gwatkin et al., 2000). Each household was then assigned a score for each asset, and the scores were summed for each household; individuals were ranked according to the total score of the household in which they resided. -

Nature Conservation in Lesotho

Nature Conservation in Lesotho Report on Current Progress and Forward Planning by Dr. Donald N. McVean IUCN Consultant Report of International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources to the Government of Lesotho prepared with the financial support of the United Nations Environment Programme Morges, Switzerland June 1977 NATURE CONSERVATION IN LESOTHO Report on Current Progress and Forward Planning by Dr. Donald N. McVean IUCN Consultant Report of International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources to the Government of Lesotho with the financial support of the United Nations Environment Programme. Morges, Switzerland June 1977 FOREWORD Following a UNEP Mission to the Kingdom of Lesotho by Mr. A.L .D. Mongi, UNEP Advisor on Conservation and Wildlife from 29 January to 3 February 1975 in which he identified urgent need for a short-term advisory consult- ancy to the Kingdom to work out details on matters related to nature conservation, the Government of Lesotho approached UNEP for the provis- ion of such a consultant. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), which works in close cooperation with UNEP in the promotion of conservation, was requested to carry out this task under UNEP/IUCN Project FP-1103-75-04. This arrangement made it possible to send an IUCN Consultant for three months the result of which is the subject of this report. IUCN acknowledges with gratitude the cooperation given to the Consultant by the Kingdom of Lesotho through the various Ministries, private bodies and individuals, and to the UNDP Resident Representative; and lastly to UNEP for making the funds available. -

Integrated Acute Food Insecurity Phase Classification

INTEGRATED ACUTE FOOD INSECURITY PHASE CLASSIFICATION MAY 16/MAR 17 THE KINGDOM OF LESOTHO IPC analysis conducted from 24 to 30 May 2016 for all 10 districts of Lesotho based on primary data collected by LVAC and partners in May 2016 and secondary data collected from Jan. 2016 onwards. Projected analysis requires an update in October 2016. AGGREGATE NUMBERS FOR WORST PERIOD KEY FOOD INSECURITY OUTCOMES AS OF MAY 2016 – JULY TO OCTOBER 2016 – Despite current analysis corresponding to harvest/post-harvest Proportions of households and number of people in need of urgent period, 19% of households had poor food consumption, and 45% had support to protect their livelihoods and reduce food gaps and classified borderline food consumption. using IPC1: In Berea, Mafeteng, Mohale’s Hoek, Quthing and Thaba-Tseka, over Thaba-Tseka 40% (48,903 people) 20% of the rural households spent more than 75% of their cash in Maseru 25% (55,623 people) food purchase. In other districts the same expenditure pattern is Mafeteng 45% (67,204 people) experienced by 10-16% of rural households. Qacha’s Nek 45% (23,950 people) Generally, 13% of households engaged in crisis and emergency Leribe 35% (86,918 people) livelihood coping strategies, indicating that households reduced food Mohale’s Hoek 33% (50,245 people) consumption rather than depleting livelihood assets Quthing 43% (48,448 people) Global Acute Malnutrition was below 5% in all districts except in Mokhotlong 25% (23,625 people) Mohale’s Hoek, which had a GAM prevalence of 6.6%. Butha Buthe 20% (16,616 people) Berea 51% (88,725 people) Total Approx. -

Lesotho 2019 Human Rights Report

LESOTHO 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy with a democratic parliamentary government. Under the constitution the king is head of state but does not actively participate in political activities. The prime minister is head of government and has executive authority. In 2017 former prime minister Pakalitha Mosisili of the Democratic Congress Party lost a vote of no confidence and a snap election. All major parties accepted the outcome, and Motsoahae Thomas Thabane of the All Basotho Convention Party (ABC) formed a coalition government and became prime minister. Mosisili transferred power peacefully to Thabane, and Mathibeli Mokhothu assumed leadership of the opposition. Local and international observers assessed the election as peaceful, credible, and transparent. The security forces consist of the Lesotho Defense Force (LDF), the Lesotho Mounted Police Service (LMPS), the National Security Service (NSS), and the Lesotho Correctional Service (LCS). The LMPS is responsible for internal security. The LDF maintains external security and may support police when the LMPS commissioner requests assistance. The NSS is an intelligence service that provides information on possible threats to internal and external security. The LDF and NSS report to the minister of defense; the LMPS, to the minister of police and public safety; and the LCS, to the minister of justice and correctional service. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) Preventive Mission in Lesotho contingent of troops, deployed to foster stability as the government moved forward with SADC-recommended security-sector reforms, departed the country in November 2018. In May the government did not meet an SADC deadline for completion of constitutional and security reforms. -

Mohale's Hoek District Council

MOHALE’S HOEK DISTRICT COUNCIL Information Handbook 2009 Handbook MOHALE’S HOEK DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL GOVERNMENT DISTRICT INFORMATION HANDBOOK June 2009 A COMPILATION OF CRUCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE DISTRICT (DISAGGREGATED COUNCIL-WISE) Ministry of local Government and Chieftainship German Technical Cooperation Department of Planning Kingdom of Lesotho Information Handbook 2009 1 handbook contents Prepared by: Department of Planning, Acronyms……………………………………………………………………………….............. 04 Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Mohale’s Hoek District Map………………………………………………………................. 05 Supported by: GTZ Lesotho Introduction………………………………………………………………………...........…….. 06 Background to Local Government in Lesotho……………………………............…………. 07 The Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Methodology…………………………………………………………………...........…………. 08 (MOLGC) through its Department of Planning, remains the owner of this handbook. However, there shall be no copy- 1. Profile of Community Councils……………………………………...……………… 09 right restrictions over the use or replication of the whole 2. Social Indicators……………………………………………………...……………… 10 or parts of this handbook. This is an approach for utiliza- 3. Gender Aspects……………………………………………………....………………. 11 tion by the interested parties and is entirely in the public domain. However, no changes shall be made 4. Agriculture………………………………………………………….………………… 12 to the handbook and reprinted thus without prior 5. Trade and Commerce…………………………………………………...…………… 13 permission of MOLGC. 6. Health…………………………………………………………………….…………… -

Lesotho Housing Profile.Pdf

HS/078/15E ISBN(Series): 978-92-1-131927-9 ISBN(Volume): 978-92-1-132686-4 UNITED NATIONS HUMAN SETTLEMENTS PROGRAMME P.O.Box 30030,Nairobi 00100,Kenya; Tel: +254-20-7626742; Fax: +254-20-7625015; [email protected] www.unhabitat.org LESOTHO HOUSING PROFILE LESOTHO HOUSING PROFILE Prepared by Graham Tipple in collaboration with the Housing Department of the Ministry of Local Government, Chieftainship and Parliamentary Affairs First published in Nairobi in October 2015 by UN-Habitat. Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme 2015 Produced by the Housing Unit United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) P. O. Box 30030, 00100 Nairobi GPO KENYA Tel: 254-020-7623120 (Central Office) www.unhabitat.org HS/078/15E ISBN(Series): 978-92-1-131927-9 ISBN(Volume): 978-92-1-132686-4 DISCLAIMER The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers of boundaries. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the United Nations, or its Member States. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Supervisor: Christophe Lalande Task Managers: Gregor Herda and Kamba Ankunda Contributors: Channe Oguzhan, Fernanda Lonardoni, Kamba Ankunda and Gregor Herda Principal Author: Graham Tipple National Profile Team Coordinator: Kabelo Lethunya Design and layout: Andrew Ondoo Financial Support: The participatory Slum Upgrading Program (PSUP), a joint initiative by the European Commission and the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) Secretariat and implemented by UN-Habitat, UNDP and the Government of Lesotho. -

Mcc Lesotho Compact 2008-2013 Evaluation Design

MCC LESOTHO COMPACT 2008-2013 MCA HEALTH PROJECT LESOTHO FINAL EVALUATION MCC-15-PO-0074 EVALUATION DESIGN June 16, 2017 HEALTHMATCH consultancies Pim de Graaf The Netherlands Page 1 of 96 Content CONTENT .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................... 4 I INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ 5 COUNTRY CONTEXT .................................................................................................................................................. 5 HEALTH PROFILE ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 HEALTH SYSTEM ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 OBJECTIVES OF THIS REPORT .................................................................................................................................... 12 2 OVERVIEW OF THE COMPACT ................................................................................................................ 13 THE HEALTH PROJECT AND IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ...................................................................................................... -

Highlights Contents

LESOTHO METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES (LEKALA LA TSA BOLEPI) Ten-Day Agrometeorological Bulletin 21st – 31st January 2005 Issue No.10/2004-05 Date of Issue: 4 February 2005 Vol. 3 …dedicated to the agricultural community … aimed at harmonizing agricultural activities with weather and climate Contents Highlights Weather Summary Page 1 q Below normal rains recorded. Rainfall Situation q Cumulative rainfall normal countrywide. Page 1 q Temperature Crops conditions good at few localities. Page 1 q Infestation of insects at some places. Crop Stage and Condition Page 1 q Low rainfall expected for next dekad. Dekadal Outlook Page 1 Rainfall and Temperature Summaries Page 2 Glossary Page 3 The Director TEL: (+266) 22324374/22324425 Lesotho Meteorological Services FAX: (+266) 22325057/22350325 Agrometeorological Section E-mail:[email protected] P.O. Box 14515 http://www.lesmet.org.ls Maseru 100, Lesotho Issue No. 10/2004-05 Vol.3 21st –31st January 2005 WEATHER SUMMARY The percentage departure from normal cumulative 11th – 20 th January 2005 rainfall ranges from -12% to 32% (Table 1). The highest cumulative rainfalls of 721.5mm, The last dekad of January was dominated by 543.9mm and 509.4mm are recorded at Oxbow, surface trough. However, there was insufficient Leribe and Qacha’s Nek (Table 1 and Fig. 3). moisture over the interior as a result only partly Mafeteng, Maseru Airport, Moshoeshoe I and cloudy and warm conditions with few Phuthiatsana stations are the only stations which thundershowers occurred. have received cumulative rainfall of less than 400mm. RAINFALL SITUATION TEMPERATURE The last ten days of January received relatively low rainfall compared to the previous dekad (11th th The country experienced near normal – 20 January 2005) which was very wet. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7, As Amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7, as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. Note for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Bureau. Compilers are strongly urged to provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Ms Limpho Motanya, Department of Water Affairs. Ministry of Natural Resources, P O Box 772, Maseru, LESOTHO. Designation date Site Reference Number 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: October 2003 3. Country: LESOTHO 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Lets`eng - la – Letsie 5. Map of site included: Refer to Annex III of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines, for detailed guidance on provision of suitable maps. a) hard copy (required for inclusion of site in the Ramsar List): yes (X) -or- no b) digital (electronic) format (optional): yes (X) -or- no 6. Geographical coordinates (latitude/longitude): The area lies between 30º 17´ 02´´ S and 30º 21´ 53´´ S; 28º 08´ 53´´ E and 28º 15´ 30´´ E xx 7. General location: Include in which part of the country and which large administrative region(s), and the location of the nearest large town. -

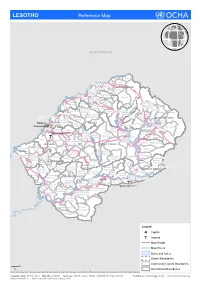

LESOTHO Reference Map

LESOTHO Reference Map SOUTH AFRICA Makhunoane Liqobong Likila Ntelle n Maisa-Phoka Ts'a-le- o d Moleka le BUTHA BUTHE a Lipelaneng C Nqechane/ Moteng Sephokong Linakeng Maputsoe Leribe Menkhoaneng Sekhobe Litjotjela Likhotola/ LERIBE Hleoheng Malaoaneng Manka/ Likhakeng Matlameng Mapholaneng/ Fobane Koeneng/ Phuthiatsana Kolojane Lipetu/ Kao Pae-la-itlhatsoa -Leribe Fenyane Litsilo -Pae-la-itlhatsoa Mokhachane/ Mamathe/Bulara Mphorosane Molika-liko Makhoroana Limamarela Tlhakanyu/Motsitseng Teyateyaneng Seshote Mapholaneng/ Majoe-Matso/ Meno/ Lekokoaneng/Maqhaka Mohatlane/ Sebetia/Khokhoba Pae-la-itlhatsoa Matsoku -Mapholaneng MOKHOTLONG Lipohong Thuapa-Kubu/ Moremoholo/ Katse Popa Senekane BEREA Moshemong Maseru Thuathe Koali/ Taung/Khubelu Mejametalana p Mokhameleli Semenanyane Mokhotlong S Maluba-lube/ Mateanong e Maseru Suoane/ m Rafolatsane Thaba-Bosiu g Ratau e Liphakoeng n Bokong n e a Ihlo-Letso/ Mazenod Maseru Moshoeshoe l Setibing/ Khotso-Ntso Sehong-hong e Tsoelike/ Moeketsane h Pontseng/ Makopoi/ k Mantsonyane Bobete p Popa_MSU a Likalaneng Mahlong Linakaneng M Thaba-Tseka/ Rothe Mofoka Nyakosoba/Makhaleng Maboloka Linakeng/Bokhoasa/Manamaneng THABA TSEKA Kolo/ MASERU Setleketseng/ Tebang/ Matsieng Tsakholo/Mapotu Seroeneg S Mashai e Boleka n Tsa-Kholo Ramabanta/ q Methalaneng/ Tajane Moeaneng u Rapo-le-boea n Khutlo-se-metsi Litsoeneng/Qalabane Maboloka/ y Sehonghong Thaba-Tsoeu/ Monyake a Lesobeng/ Mohlanapeng Mathebe/ n Sehlaba-thebe/ Thabaneng Ribaneng e Takalatsa Likhoele Moshebi/ Kokome/ MAFETENG Semonkong Leseling/ -

Competition Issues in the Transport Sector in Lesotho

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Competition issues in the Transport Sector in Lesotho By Chabeli J. RAMOLISE New York and Geneva, 2011 The views expressed in this study are those of the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNCTAD Secretariat. NOTE UNCTAD serves as the focal point within the United Nations Secretariat for all matters related to competition policy. UNCTAD seeks to further the understanding of the nature of competition law and policy and its contribution to development and to create an enabling environment for an efficient functioning of markets. UNCTAD’s work is carried out through intergovernmental deliberations, capacity building activities, policy advice, and research and analysis on the interface between competition policy and development. UNCTAD’s work on competition law and policies falls within the framework of the Set of Multilaterally Agreed Principles and Rules for the Control of Restrictive Business Practices (the “United Nations Set of Principles and Rules on Competition”), adopted by the General Assembly in 1980. The set seeks, inter alia, to assist developing countries in adopting and enforcing effective competition law and policy that are suited to their development needs and economic situation. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. -

Second State Of

Second State of the Environment 2002 Report Lesotho Lesotho Second State of the Environment Report 2002 Authors: Chaba Mokuku, Tsepo Lepono, Motlatsi Mokhothu Thabo Khasipe and Tsepo Mokuku Reviewer: Motebang Emmanuel Pomela Published by National Environment Secretariat Ministry of Tourism, Environment & Culture Government of Lesotho P.O. Box 10993, Maseru 100, Lesotho ISBN 99911-632-6-0 This document should be cited as Lesotho Second State of the Environment Report for 2002. Copyright © 2004 National Environment Secretariat. All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Design and production by Pheko Mathibeli, graphic designer, media practitioner & chartered public relations practitioner Set in Century Gothic, Premium True Type and Optima Lesotho, 2002 3 Contents List of Tables 8 Industrial Structure: Sectoral Composition 34 List of Figures 9 Industrial Structure: Growth Rates 36 List of Plates 10 Population Growth 37 Acknowledgements 11 Rural to Urban Migration 37 Foreword 12 Incidence of Poverty 38 Executive Summary 14 Inappropriate Technologies 38 State and impacts: trends 38 Introduction 24 Human Development Trends 38 Poverty and Income Distribution 44 Socio-Economic and Cultural Environment. 26 Agriculture and Food Security 45 People, Economy and Development Ensuring Long and Healthy Lives 46 Socio-Economic Dimension 26 Ensuring