Mcc Lesotho Compact 2008-2013 Evaluation Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesotho 2019 Human Rights Report

LESOTHO 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy with a democratic parliamentary government. Under the constitution the king is head of state but does not actively participate in political activities. The prime minister is head of government and has executive authority. In 2017 former prime minister Pakalitha Mosisili of the Democratic Congress Party lost a vote of no confidence and a snap election. All major parties accepted the outcome, and Motsoahae Thomas Thabane of the All Basotho Convention Party (ABC) formed a coalition government and became prime minister. Mosisili transferred power peacefully to Thabane, and Mathibeli Mokhothu assumed leadership of the opposition. Local and international observers assessed the election as peaceful, credible, and transparent. The security forces consist of the Lesotho Defense Force (LDF), the Lesotho Mounted Police Service (LMPS), the National Security Service (NSS), and the Lesotho Correctional Service (LCS). The LMPS is responsible for internal security. The LDF maintains external security and may support police when the LMPS commissioner requests assistance. The NSS is an intelligence service that provides information on possible threats to internal and external security. The LDF and NSS report to the minister of defense; the LMPS, to the minister of police and public safety; and the LCS, to the minister of justice and correctional service. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) Preventive Mission in Lesotho contingent of troops, deployed to foster stability as the government moved forward with SADC-recommended security-sector reforms, departed the country in November 2018. In May the government did not meet an SADC deadline for completion of constitutional and security reforms. -

Private Solutions for Infrastructure in Lesotho

A COUNTRY FRAMEWORK REPORT Private Solutions for Infrastructure in Lesotho PUBLIC-PRIVATE INFRASTRUCTURE ADVISORY FACILITY THE WORLD BANK A Country Framework Report Private Solutions for Infrastructure in Lesotho THE WORLD BANK Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2004 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ this report are entirely those of the authors and should not be THE WORLD BANK attributed in any manner to the Public-Private Infrastructure 1818 H Street,NW Advisory Facility (PPIAF) or to the World Bank, to its affil- Washington, DC 20433, USA iated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Telephone 202-473-1000 Directors or the countries they represent. Internet www.worldbank.org Neither PPIAF nor the World Bank guarantees the accu- E-mail [email protected] racy of the data included in this publication or accepts All rights reserved responsibility for any consequence of their use. The bound- Manufactured in the aries, colors, denominations, and other information shown United States of America on any map in this report do not imply on the part of PPIAF or the World Bank Group any judgment on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copyright is held by the World Bank on behalf of both the World Bank and PPIAF. Dissemination of this work is encouraged, and the World Bank will normally grant per- mission promptly and, when reproduction is for non-commercial purposes, without asking a fee. Permission to photocopy portions of this publication should be addressed to: Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, U.S.A., telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, or through the Internet at www.copyright.com For questions about this publication or information about ordering more copies, please refer to the PPIAF web- site or contact PPIAF c/o the World Bank, 1818 H. -

Mohale's Hoek District Council

MOHALE’S HOEK DISTRICT COUNCIL Information Handbook 2009 Handbook MOHALE’S HOEK DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL GOVERNMENT DISTRICT INFORMATION HANDBOOK June 2009 A COMPILATION OF CRUCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE DISTRICT (DISAGGREGATED COUNCIL-WISE) Ministry of local Government and Chieftainship German Technical Cooperation Department of Planning Kingdom of Lesotho Information Handbook 2009 1 handbook contents Prepared by: Department of Planning, Acronyms……………………………………………………………………………….............. 04 Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Mohale’s Hoek District Map………………………………………………………................. 05 Supported by: GTZ Lesotho Introduction………………………………………………………………………...........…….. 06 Background to Local Government in Lesotho……………………………............…………. 07 The Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Methodology…………………………………………………………………...........…………. 08 (MOLGC) through its Department of Planning, remains the owner of this handbook. However, there shall be no copy- 1. Profile of Community Councils……………………………………...……………… 09 right restrictions over the use or replication of the whole 2. Social Indicators……………………………………………………...……………… 10 or parts of this handbook. This is an approach for utiliza- 3. Gender Aspects……………………………………………………....………………. 11 tion by the interested parties and is entirely in the public domain. However, no changes shall be made 4. Agriculture………………………………………………………….………………… 12 to the handbook and reprinted thus without prior 5. Trade and Commerce…………………………………………………...…………… 13 permission of MOLGC. 6. Health…………………………………………………………………….…………… -

Highlights Contents

LESOTHO METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES (LEKALA LA TSA BOLEPI) Ten-Day Agrometeorological Bulletin 21st – 31st January 2005 Issue No.10/2004-05 Date of Issue: 4 February 2005 Vol. 3 …dedicated to the agricultural community … aimed at harmonizing agricultural activities with weather and climate Contents Highlights Weather Summary Page 1 q Below normal rains recorded. Rainfall Situation q Cumulative rainfall normal countrywide. Page 1 q Temperature Crops conditions good at few localities. Page 1 q Infestation of insects at some places. Crop Stage and Condition Page 1 q Low rainfall expected for next dekad. Dekadal Outlook Page 1 Rainfall and Temperature Summaries Page 2 Glossary Page 3 The Director TEL: (+266) 22324374/22324425 Lesotho Meteorological Services FAX: (+266) 22325057/22350325 Agrometeorological Section E-mail:[email protected] P.O. Box 14515 http://www.lesmet.org.ls Maseru 100, Lesotho Issue No. 10/2004-05 Vol.3 21st –31st January 2005 WEATHER SUMMARY The percentage departure from normal cumulative 11th – 20 th January 2005 rainfall ranges from -12% to 32% (Table 1). The highest cumulative rainfalls of 721.5mm, The last dekad of January was dominated by 543.9mm and 509.4mm are recorded at Oxbow, surface trough. However, there was insufficient Leribe and Qacha’s Nek (Table 1 and Fig. 3). moisture over the interior as a result only partly Mafeteng, Maseru Airport, Moshoeshoe I and cloudy and warm conditions with few Phuthiatsana stations are the only stations which thundershowers occurred. have received cumulative rainfall of less than 400mm. RAINFALL SITUATION TEMPERATURE The last ten days of January received relatively low rainfall compared to the previous dekad (11th th The country experienced near normal – 20 January 2005) which was very wet. -

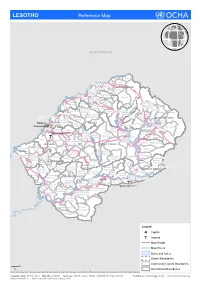

LESOTHO Reference Map

LESOTHO Reference Map SOUTH AFRICA Makhunoane Liqobong Likila Ntelle n Maisa-Phoka Ts'a-le- o d Moleka le BUTHA BUTHE a Lipelaneng C Nqechane/ Moteng Sephokong Linakeng Maputsoe Leribe Menkhoaneng Sekhobe Litjotjela Likhotola/ LERIBE Hleoheng Malaoaneng Manka/ Likhakeng Matlameng Mapholaneng/ Fobane Koeneng/ Phuthiatsana Kolojane Lipetu/ Kao Pae-la-itlhatsoa -Leribe Fenyane Litsilo -Pae-la-itlhatsoa Mokhachane/ Mamathe/Bulara Mphorosane Molika-liko Makhoroana Limamarela Tlhakanyu/Motsitseng Teyateyaneng Seshote Mapholaneng/ Majoe-Matso/ Meno/ Lekokoaneng/Maqhaka Mohatlane/ Sebetia/Khokhoba Pae-la-itlhatsoa Matsoku -Mapholaneng MOKHOTLONG Lipohong Thuapa-Kubu/ Moremoholo/ Katse Popa Senekane BEREA Moshemong Maseru Thuathe Koali/ Taung/Khubelu Mejametalana p Mokhameleli Semenanyane Mokhotlong S Maluba-lube/ Mateanong e Maseru Suoane/ m Rafolatsane Thaba-Bosiu g Ratau e Liphakoeng n Bokong n e a Ihlo-Letso/ Mazenod Maseru Moshoeshoe l Setibing/ Khotso-Ntso Sehong-hong e Tsoelike/ Moeketsane h Pontseng/ Makopoi/ k Mantsonyane Bobete p Popa_MSU a Likalaneng Mahlong Linakaneng M Thaba-Tseka/ Rothe Mofoka Nyakosoba/Makhaleng Maboloka Linakeng/Bokhoasa/Manamaneng THABA TSEKA Kolo/ MASERU Setleketseng/ Tebang/ Matsieng Tsakholo/Mapotu Seroeneg S Mashai e Boleka n Tsa-Kholo Ramabanta/ q Methalaneng/ Tajane Moeaneng u Rapo-le-boea n Khutlo-se-metsi Litsoeneng/Qalabane Maboloka/ y Sehonghong Thaba-Tsoeu/ Monyake a Lesobeng/ Mohlanapeng Mathebe/ n Sehlaba-thebe/ Thabaneng Ribaneng e Takalatsa Likhoele Moshebi/ Kokome/ MAFETENG Semonkong Leseling/ -

Competition Issues in the Transport Sector in Lesotho

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Competition issues in the Transport Sector in Lesotho By Chabeli J. RAMOLISE New York and Geneva, 2011 The views expressed in this study are those of the author do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNCTAD Secretariat. NOTE UNCTAD serves as the focal point within the United Nations Secretariat for all matters related to competition policy. UNCTAD seeks to further the understanding of the nature of competition law and policy and its contribution to development and to create an enabling environment for an efficient functioning of markets. UNCTAD’s work is carried out through intergovernmental deliberations, capacity building activities, policy advice, and research and analysis on the interface between competition policy and development. UNCTAD’s work on competition law and policies falls within the framework of the Set of Multilaterally Agreed Principles and Rules for the Control of Restrictive Business Practices (the “United Nations Set of Principles and Rules on Competition”), adopted by the General Assembly in 1980. The set seeks, inter alia, to assist developing countries in adopting and enforcing effective competition law and policy that are suited to their development needs and economic situation. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. -

Second State Of

Second State of the Environment 2002 Report Lesotho Lesotho Second State of the Environment Report 2002 Authors: Chaba Mokuku, Tsepo Lepono, Motlatsi Mokhothu Thabo Khasipe and Tsepo Mokuku Reviewer: Motebang Emmanuel Pomela Published by National Environment Secretariat Ministry of Tourism, Environment & Culture Government of Lesotho P.O. Box 10993, Maseru 100, Lesotho ISBN 99911-632-6-0 This document should be cited as Lesotho Second State of the Environment Report for 2002. Copyright © 2004 National Environment Secretariat. All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Design and production by Pheko Mathibeli, graphic designer, media practitioner & chartered public relations practitioner Set in Century Gothic, Premium True Type and Optima Lesotho, 2002 3 Contents List of Tables 8 Industrial Structure: Sectoral Composition 34 List of Figures 9 Industrial Structure: Growth Rates 36 List of Plates 10 Population Growth 37 Acknowledgements 11 Rural to Urban Migration 37 Foreword 12 Incidence of Poverty 38 Executive Summary 14 Inappropriate Technologies 38 State and impacts: trends 38 Introduction 24 Human Development Trends 38 Poverty and Income Distribution 44 Socio-Economic and Cultural Environment. 26 Agriculture and Food Security 45 People, Economy and Development Ensuring Long and Healthy Lives 46 Socio-Economic Dimension 26 Ensuring -

Annexure 1: Lesotho Villages and Their Corresponding Code

Annexure 1: Lesotho villages and their corresponding code ID Village 46 Tlhanyaku 92 Rafolatsane 1 Liqobong 47 Bela-Bela 93 Khokhoba 2 Boiketsiso 48 Mphorosane 94 Liphakoeng (Mokhotlong) 3 Makhunoane 49 Mokhachane 95 Bokong 4 Qholaqhoe 50 'Mamathe 96 Sehong-hong 5 Namahali 51 Seshote 97 Setibing 6 Maama 52 Lehana-le-molapa 98 Khohlontso 7 Tumane 53 Majoe-Mats'o 99 Bobete 8 Matlakeng 54 Meno 100 Bobatsi 9 Chaba 55 Mapoteng 101 Mazenod 10 Mopeli 56 'Makhoroana 102 Makopoi 11 Qalo 57 Malotoaneng 103 Popa (Maseru) 12 Khukhune 58 Sebetia 104 Moeketsane 13 Nqechane 59 Lekokoaneng 105 Rothe 14 Butha-Buthe Urban 60 Mapholaneng 106 Linakeng (Mokhotlong) 15 Sekubu 61 Suoane 107 Mantsonyane 16 Tsime 62 'Meta 108 Mofoka 17 Soloane 63 Mohatlane 109 Maboloka (Thaba Tseka) 18 Linakeng (Butha Buthe) 64 Motsitseng 110 Likalaneng 19 Likhutlong 65 Mongolo 111 Roma 20 Leribe 66 Lebese 112 Lirahalibonoe 21 Ha Mots'eare 67 Mika 113 Nyakosoba 22 Mohobollo 68 Koali 114 Thaba Moei 23 Pela Ts'oeu 69 Maqhaka 115 Linakeng (Thaba Tseka) 24 Hlotse 70 Matsoku 116 Manamaneng 25 Maputsoe 71 Malingoaneng 117 Makhaleng 26 Pela-ts'oeu 72 Kosetabole 118 Lits'oeneng 27 Tsikoane 73 Moshemong 119 Bokhoasa 28 Likhakeng 74 Popa (Mokhotlong) 120 Matsieng 29 Matlameng 75 Foso 121 Kolo 30 Peka 76 Taung 122 Mohlanapeng 31 Mahobong 77 Semenanyane 123 Mochochoko 32 Hleoheng 78 Thupa-Kubu 124 Mahlong 33 Mothae 79 Mokhameleli 125 Setleketseng 34 Pitseng 80 Khamolane 126 Thaba-nts'o 35 Thaba Phats'oa (Leribe) 81 Thuathe 127 Tsakholo 36 Lejone 82 Tsoelike 128 Serooeng 37 Mokomahatsi 83 -

WFP Lesotho Country Brief October 2020

In Numbers WFP Lesotho 2,026 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Lesotho (10th Country Brief November 2020) October 2020 44 deaths 1,029 recoveries US$16.7 million six months (Nov 2020 - Apr 2021) net funding requirements, representing 68 percent of total six- month requirements 428,250 people 52% 48% targeted in 2020 Operational Context Operational Updates More than half (57 percent) of Lesotho’s population live on less than one dollar per day. GDP stands at USD 2.3 billion while its national GDI per capita is USD 1,270 (World • The Minister of Health and Minister of Home th Bank). Revenue from the Southern African Customs Union Affairs notified the public that on the 25 (SACU) contributes a significant proportion to Lesotho’s October that the permitted categories of national budget. The Government allocates 7 percent of travellers in Lesotho remain as follows: patients, its national budget to social protection programmes such business travellers, all classes of scholars, as school meals, pension for the elderly, child grants and migrant workers, pensioners, retrenched public works. Basotho migrant workers, Basotho returnees The population’s high vulnerability is exacerbated by and travellers with exceptional special needs. recurring climatic hazards, including droughts, early frost, Everyone eligible for travelling is required to and a low performing economy. Twenty-nine percent of present a valid, negative PCR COVID-19 people below the age of 35 are unemployed. The country certificate conducted within 72 hours of travel is also characterized by an extremely high HIV prevalence • Cash assistance is ongoing in the urban councils rate (25.6 percent: 30.4 percent for women and 20.8 for of Maseru, Mafeteng, Mohale's Hoek, Quthing men), with care needed for more than 250,000 orphaned children, most of whom lost their parents to AIDS. -

Covid-19 Bulletin Mozambique Zinbabwe Namibia Botswana Madagascar

ReSAKSS-SA logo - main, white background 015 SA Regional Strategic Analysis and Knowledge Support System by AKADEMIYA2063 & IWMI 2 AKADEMIYA2063 - December 1 /December 7 -2020 tunisia morocco ALGERIA libya western EGYPT sahara mauritania mali The ExpertiseAKADEMIYA We Need. The Africa We Want. niger Eritrea senegal chad sudan Guinea-Bissau burkina faso guinea benin nigeria ethiopia sierra leone ivory ghana coast central africa republic liberia togo cameroon Equatorial uganda somalia Guinea republic of the congo democratic kenya gabon republic rwanda of the congo burundi tanzania angola malawi zambia Covid-19 Bulletin mozambique zinbabwe namibia botswana madagascar south africa Maize Flour Price trends in rural LOCAL STAPLE FOOD districts and urban districts of MARKET DYNAMICS UNDER COVID Lesotho under COVID-19 The pandemic is likely to be more disruptive to local food markets and thus have more serious Sibusiso Nhlengethwa, Research offi cer Statistics Resakss-SA,IWMI, Greenwell eff ects on the poorest and most vulnerable Matchaya, ReSAKSS-SA Coordinator, IWMI; ReSAKSS-SA, IWMI; Jacob Greffi ths, Research groups and communities than any of the crises in recent years. This is because the poor and offi cer Agricultural Economics, ReSAKSS-SA, IWMI; and Bhekiwe Fakudze, Research vulnerable are aff ected by changes in local Offi cer Agricultural Economics, ReSAKSS-SA, IWMI; Corresponding Author’s email: food staple prices signifi cantly more than other [email protected] population groups, not only because of more limited purchasing power but also because of This bulletin focuses on the relationship between maize fl our price diff erences in consumption baskets. Moreover, trends and the actions in response to COVID-19 Pandemic in Lesotho. -

Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in LESOTHO Research Highlights – Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in Lesotho

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in LESOTHO Research Highlights – Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in Lesotho Funded by ‘Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme’ (ASAP) Phase 2. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Produced by the University of Cape Town Undertaken in support of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) by: African Climate & Development Initiative (www.acdi.uct.ac.za) Climate System Analysis Group (www.csag.uct.ac.za) Environmental Policy Research Unit (www.epru.uct.ac.za) Recommended citation: Hunter. R., Crespo. O., Coldrey, K, Cronin, K, New, M. 2020. Research Highlights – Climate Change and Future Crop Suitability in Lesotho. University of Cape Town, South Africa, undertaken in support of Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme’ (ASAP) Phase 2. International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Rome. The content and presentation of material in this report is the sole responsibility of the Authors and does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Fund for Agricultural Development of the United Nations. The project team gratefully acknowledges the support of IFAD towards this research and in particular the IFAD country office and project staff. The project team thanks the various stakeholders and contributors who have shared their knowledge and time during this study. CONTENTS Background and context . 1 Summary results . 2 Method and Approach . 3 Impacts........................................................................................3 Figure 1. Demonstration example of the distribution of crop suitability index. generated using EcoCrop ........4 Adaptive Capacity ...............................................................................5 Table 1. Ranked Adaptive Capacity (AC) indicator scores for all regions of Lesotho ..........................5 Climate projections . 6 Projected changes to Temperature in Lesotho by 2050 . -

IRISH AID Sechaba Consultants an EVALUATION of the QACHA's NEK

AN EVALUATION of the QACHA’S NEK VILLAGE WATER SUPPLY PROJECT FUNDED BY IRISH AID by Pat Goss and David Hall Sechaba Consultants AUGUST 1996 824Ls 16438 1 LIBRARY IRC P0 Box 93190, 2509 AD THE HAGUE Tel.: +31 70 30 689 80 Fax: ÷3170 935 899 64 LO:BARCODE: 161’3c1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 BriefHistory of Irish Aid Involvement 1 1.2 Evaluation Methodology 2 1.3 DRWS Project Cycle 3 1.4 Staffing Levels 4 2.0 Production Output 5 3.0 Data Base Findings 6 3.1 Functioning S 3.2 Condition 8 3.3 Levels of Service 9 3.4 Community management Indicators 11 4.0 Village Perceptions 12 4.1 Perceptions ofthe Beneficiaries 12 4.2 Perceptions of Village Water Committee Members 15 5.0 StaffPerceptions 17 6.0 Maintenance 21 7.0 Issues Emanating from Past Reviews 21 7.1 Localisation 22 7.2 Targeting 24 7.3 Water Quality 24 7.4 Sanitation and Health Education 25 8.0 Recent Policies 26 8.1 Area Based Approach 26 8.2 Spring Measurements 26 8.3 Design Files 27 8.4 Protection ofTraditional Springs 28 9.0 NGO Activities 29 1O.0 Costs and Full Coverage Implications 30 11.0 Conclusions and Summary 33 LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1 Population Served by VWSS after Office Built 2 Table 2 Staffing in Qacha’s Nek 4 Table 3 Comparisons of Planned and Actual Output 5 Table 4 Average Population Served per Year per Field Staff 6 Table 5 Summary of Projects included in Data Base Analysis 7 Table 6 Populations per Project and per Village S Table 7 Functioning 8 Table 8 Population per Collection Point (categories) 10 Table 9 Population per Collection Point (mean) 10 Table 10 Households travelling> 150 m.