The Second World War's Impact on the Progressive Educational Movement: Assessing Its Role

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploitation of the American Progressive Education Movement in Japan’S Postwar Education Reform, 1946-1950

Disarming the Nation, Disarming the Mind: Exploitation of the American Progressive Education Movement in Japan’s Postwar Education Reform, 1946-1950 Kevin Lin Advised by Dr. Talya Zemach-Bersin and Dr. Sarah LeBaron von Baeyer Education Studies Scholars Program Senior Capstone Project Yale University May 2019 i. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Part One. The Rise of Progressive Education 6 Part Two. Social Reconstructionists Aboard the USEM: Stoddard and Counts 12 Part Three. Empire Building in the Cold War 29 Conclusion 32 Bibliography 35 1 Introduction On February 26, 1946, five months after the end of World War II in Asia, a cohort of 27 esteemed American professionals from across the United States boarded two C-54 aircraft at Hamilton Field, a U.S. Air Force base near San Francisco. Following a stop in Honolulu to attend briefings with University of Hawaii faculty, the group was promptly jettisoned across the Pacific Ocean to war-torn Japan.1 Included in this cohort of Americans traveling to Japan was an overwhelming number of educators and educational professionals: among them were George S. Counts, a progressive educator and vice president of the American Federation Teachers’ (AFT) labor union and George D. Stoddard, state commissioner of education for New York and a member of the U.S. delegation to the first meeting of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).2,3 This group of American professionals was carefully curated by the State Department not only for their diversity of backgrounds but also for -

AS Vimed IROM SOCIOLOGICAL and PHILOSOPHICAL BASES

THE PE0BLES4 OF INDOCTRINATION: AS VimED IROM SOCIOLOGICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL BASES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By MiOhio Nagai, B.A., A,M. The Ohio State University 1952 Approvi Adviser H. Gordon flullfish AClSilOWLEDGMiiMT It would be diriicult to express adequately my appreciation of the contributions made by many persons to this study. I first wish to express my gratitude to Dr. H. Gordon Hullfish, my adviser, wnose sincere guidance, generosity, and patience have led me from the first stage of learning in English in July, 194-9, up to the very last minute of completing this dissertation in May, 1952. I am very much indebted to Dr. Aurt H. Wolff whose wisdom and painstaking guidance have been of invaluable help in the writing of this dissertation. Likewise my indebtedness is due Dr. Alan E. Griffin and Dr. Lloyd Williams who read the complete manuscript and made numerous valuable corrections and suggestions. I also wish to express my appreciation for the intellectual stimulation gained for contacts with Dr. John W. Dennett and Mr. Iwao Ishino. Acknowledgment of a less specific, but not necessarily of less important value, is due Dr. Ervin E. Lewis whose kindness guided my first steps in this new land, finally, I wish to thank my wife, Mieko Nagai, without whose help this dissertation might not have been completed. MIGHIO NAGAI 909454 XI TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I INTRODUCTION.......................... 1 I Dictionary Definition.............................. 3 II The Indoctrination Controversy...... -

Time Line of the Progressive Era from the Idea of America™

Time Line of The Progressive Era From The Idea of America™ Date Event Description March 3, Pennsylvania Mine Following an 1869 fire in an Avondale mine that kills 110 1870 Safety Act of 1870 workers, Pennsylvania passes the country's first coal mine safety passed law, mandating that mines have an emergency exit and ventilation. November Woman’s Christian Barred from traditional politics, groups such as the Woman’s 1874 Temperance Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) allow women a public Union founded platform to participate in issues of the day. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, the WCTU supports a national Prohibition political party and, by 1890, counts 150,000 members. February 4, Interstate The Interstate Commerce Act creates the Interstate Commerce 1887 Commerce act Commission to address price-fixing in the railroad industry. The passed Act is amended over the years to monitor new forms of interstate transportation, such as buses and trucks. September Hull House opens Jane Addams establishes Hull House in Chicago as a 1889 in Chicago “settlement house” for the needy. Addams and her colleagues, such as Florence Kelley, dedicate themselves to safe housing in the inner city, and call on lawmakers to bring about reforms: ending child labor, instituting better factory working conditions, and compulsory education. In 1931, Addams is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. November “White Caps” Led by Juan Jose Herrerra, the “White Caps” (Las Gorras 1889 released from Blancas) protest big business’s monopolization of land and prison resources in the New Mexico territory by destroying cattlemen’s fences. The group’s leaders gain popular support upon their release from prison in 1889. -

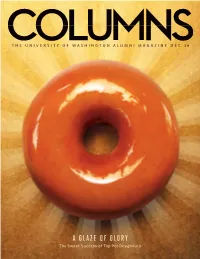

A GLAZE of GLORY the Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ALUMNI MAGAZINE DEC 1 4 A GLAZE OF GLORY The Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORTATION RUBY // RISK MANAGEMENT // BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE // INFORMATION SYSTEMS PROJECT MANAGEMENT // CONTENT STRATEGY // ORACLE DATABASE ADMIN LOCALIZATION // PARALEGAL // MACHINE LEARNING // SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH // GERONTOLOGY // BIOTECHNOLOGY // CIVIL ENGINEERING DEVOPS // DATA SCIENCE // MECHANICAL ENGINEERING // HEALTH CARE // HTML CONTENT STRATEGY // EDUCATION // PROJECT MANAGEMENT // INFORMATICS STATISTICAL ANALYSIS // E-LEARNING // CLOUD DATA MANAGEMENT // EDITING C++ // INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING // LEADERSHIP // BIOSCIENCE // LINGUISTICS INFORMATION SCIENCE // AERONAUTICS & ASTRONAUTICS // APPLIED MATHEMATICS CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING // GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS // PYTHON UW ONLINE 2 COLUMNS MAGAZINE ONLINE.UW.EDU JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // -

Critical Education

Critical Education Volume 7 Number 4 March 1, 2016 ISSN 1920-4125 Reconstruction of the Fables The Myth of Education for Democracy, Social Reconstruction and Education for Democratic Citizenship Todd S. Hawley Kent State University Andrew L. Hostetler Peabody College at Vanderbilt University Evan Mooney Montclair State University Citation: Hawley T. S., Hostetler, A. L., & Mooney, E. (2016). Reconstruction of the fables: The myth of education for democracy, social reconstruction and education for democratic citizenship. Critical Education, 7(4). Retrieved from http://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/criticaled/article/view/186116 Abstract A central goal of social studies education is to prepare students for citizenship in a democracy. Further, trends in the social, political, and economic circumstances, currently and historically in American education and society broadly suggest that: 1) a need for change exists, 2) that change is possible and can be brought about through a reconsideration of social reconstructionist ideas and values, especially those espoused by George Counts, and 3) that social studies teachers and teacher educators can work toward this change through educational practices. In this paper, we argue for these three points through a critical discussion of a perpetuated myth of democratic education. Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the author(s) and Critical Education, it is distributed for non-commercial purposes only, and no alteration or transformation is made in the work. More details of this Creative Commons license are available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. All other uses must be approved by the author(s) or Critical Education. -

Roaring Twenties,”

1 THIS IS AN OPTIONAL ENRICHMENT ASSIGNMENT. PRINT AND COMPLETE IN INK. Name:________________________________________ Class Period:_____ The Modern Era of the “Roaring Twenties,” Reading Assignment: Chapter 23 in AMSCO or other resource covering the 1920s. Mastery of the course and AP exam await all who choose to process the information as they read/receive. This is an optional assignment. So… young Jedi… what is your choice? Do? Or do not? There is no try. Pictured at left: Al Capone, Louis Armstrong, Flappers, John Scopes, Babe Ruth, public domain photos, WikiCommons) Directions: 1. Pre-Read: Read the prompts/questions within this guide before you read the chapter. 2. Skim: Flip through the chapter and note titles and subtitles. Look at images and read captions. Get a feel for the content you are about to read. 3. Read/Analyze: Read the chapter. If you have your own copy of AMSCO, Highlight key events and people as you read. Remember, the goal is not to “fish” for a specific answer(s) to reading guide questions, but to consider questions in order to critically understand what you read! 4. Write: Write (do not type) your notes and analysis in the spaces provided. Complete it in INK! Learning Goals: Defend or refute the following statement: The American economy and way of life dramatically changed during the 1920s as consumerism became the new American ideal. Identify and evaluate specific ways the culture of modernism in science, the arts, and entertainment conflicted with religious fundamentalism, nativism, and Prohibition. To what extent did the 1920s witness economic, social, and political gains for African Americans and women? To what extent did these years “roar?” To what extent was American foreign policy in the 1920s isolationist? Key Concepts FOR PERIOD 7: Key Concept 7.1: Growth expanded opportunity, while economic instability led to new efforts to reform U.S. -

Social Studies and the Social Order: Transmission Or Transformation?

Research and Practice “Research & Practice,” established early in 2001, features educational research that is directly relevant to the work of classroom teachers. Here, Social Studies and I invited William Stanley to bring a historical perspective to the peren- nial question, “Should social studies the Social Order: teachers work to transmit the status quo or to transform it?” Transmission or —Walter C. Parker, “Research and Practice” Editor, University of Transformation? Washington, Seattle. William B. Stanley Should social studies educators The Quest for Democracy and schools are places where chil- transmit or transform the social order? Debates over education reform take dren receive formal training as citizens. By “transform” I do not mean the com- place within a powerful historical and Democracy is also a process or form mon view that education should make cultural context. In the United States, of life rather than a fixed end in itself, society better (e.g., lead to scientific schooling is generally understood as and we should regard any democratic breakthroughs, eradicate disease, and an integral component of a democratic society as a work in progress.1 Thus, increase productivity). Rather, I am society. To the extent we are a demo- democratic society is something we are referring to approaches to education cratic society, one could argue that edu- always trying simultaneously to main- that are critical of the dominant social cation for social transformation could tain and reconstruct, and education is order and motivated by a desire to be anti-democratic, a view held by essential to this process. ensure both political and economic many conservatives. -

Teaching the Progressive Era Through the Life and Accomplishments of Jane Addams Kacy J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Teaching the Progressive Era through the life and accomplishments of Jane Addams Kacy J. Taylor Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Kacy J., "Teaching the Progressive Era through the life and accomplishments of Jane Addams" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 659. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/659 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING THE PROGRESSIVE ERA THROUGH THE LIFE AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF JANE ADDAMS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Kacy J. Taylor B.S. Louisiana State University, 1997 December 2005 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….iii Introduction……………………………………………………………………….………1 Chapter 1 Situating Jane Addams in American History…………………………………...8 2 From Religion to Spirituality………………………………………………….20 3 Spirituality Translates to Pragmatism…………………………………………35 4 Pragmatism -

How the National Guard Grew out of Progressive Era Reforms Matthew Am Rgis Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2016 America's Progressive Army: How the National Guard grew out of Progressive Era Reforms Matthew aM rgis Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Margis, Matthew, "America's Progressive Army: How the National Guard grew out of Progressive Era Reforms" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 15764. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/15764 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America’s progressive army: How the National Guard grew out of progressive era reforms by Matthew J. Margis A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural, Agricultural, Technological, Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Timothy Wolters, Major Professor Julie Courtwright Jeffrey Bremer Amy Bix John Monroe Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2016 Copyright © Matthew J. Margis, 2016. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my parents, and the loving memory of Anna Pattarozzi, -

Indigenous and Settler Violence During the Gilded Age and Progressive Era John R

Indigenous and Settler Violence during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era John R. Legg, George Mason University The absence of Indigenous historical perspectives creates a lacuna in the historiography of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. For the first eight years of the Journal of the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, zero articles written about or by Native Americans can be found within its pages. By 2010, however, a roundtable of leading Gilded Age and Progressive Era scholars critically examined the reasons why “Native Americans often slipped out of national consciousness by the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.”1 By 2015, the Journal offered a special issue on the importance of Indigenous histories during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a “period of tremendous violence perpetuated on Indigenous communities,” wrote the editors Boyd Cothran and C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa.2 It is the observation of Indigenous histories on the periphery of Gilded Age and Progressive Era that inspires a reevaluation of the historiographical contributions that highlight Indigenous survival through the onslaught of settler colonial violence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The purpose of this microsyllabus seeks to challenge these past historiographical omissions by re-centering works that delve into the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and experience of settler colonial violence during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. Ultimately, this microsyllabus helps us unravel two streams of historiographical themes: physical violence and structural violence. Violence does not always have to be physical, but can manifest in different forms: oppression, limiting people’s rights, their access to legal representation, their dehumanization through exclusion and segregation, as well as the production of memory. -

The Progressive Movement for the Recall, 1890S-1920

Published in: The New England Journal of History Winter, 2001, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 59-83 Power To The People: The Progressive Movement for the Recall, 1890s-1920 Rod Farmer Rod Farmer, Ph.D. Franklin Hall 252 Main St. University of Maine at Farmington Farmington, Maine 04938 Phone: (207) 778-7161 (office) (207) 778-9298 (home) Email: [email protected] Fax: 207 778-7157 Historian Warren Susman said of the people of the United States that: “The American is most characteristically a reformer and his history a series of reforms.” Susman saw “an almost continual impulse to reform from the days of the first English settlers on this continent who 1 proposed from the start nothing less than.....the establishment of the Kingdom of God.” Each generation of Americans has had its particular collection of reform efforts. That period known as the Progressive Era, from the 1890s to around 1920, brought a great change to American life by implanting in the nation the idea that government should be more proactive in solving economic and social problems and more responsible for creating a just and humane society. However, for most progressives, this enlarged government was also to be a more democratic government, because only a more democratic government could be trusted with the new powers and responsibilities. Historian Arthur S. Link found that, beginning in the 1890s, there “were many progressive movements on many levels seeking sometimes contradictory objectives” and that “despite its actual diversity and inner tensions it did seem to have unity; that is, it seemed to share 2 common ideals and objectives.” This paper will hold that the democratic ideal was one of those common ideals shared by most progressives, and this ideal can be identified in the crusade for the recall. -

Progressive Era: the Roaring Twenties

Name: _________________________________________ Date: __________ Period: __________ Directions: Close read and annotation. Before reading, take note of the items you should be looking for in the text and how they should be annotated. 1. Underline or highlight and annotate with an A the following: Evidence of where advertising helped create the idea of what life should be like. 2. Underline or highlight and annotate which B D the following: Which of the following sentences from the article BEST demonstrates the idea that A merica stood at a crossroads between advancement and tradition. 3. Determine what the central idea of the article is and write it here: 4. Underline or highlight and annotate with a C I the following: S entences that help to develop the CENTRAL idea of the article? Progressive Era: The Roaring Twenties By Joshua Zeitz, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, adapted by Newsela staff 12/14/2016 TOP: Russell Patterson's "Where There's Smoke There's Fire," showing a fashionably dressed woman of the time, often called a flapper, was painted around 1925. Courtesy of Library of Congress. BOTTOM: Calvin Coolidge in the late 1910s. The 1920s heralded a dramatic break between America’s past and future. Before World War I (1914-1918), the country remained culturally and psychologically rooted in the past. In the 1920s, America seemed to usher in a more modern era. The most vivid impressions of the 1920s are of flappers, movie palaces, radio empires, and Prohibition, the nationwide ban on alcohol that led to people making alcohol and drinking it in secret.