Indigenous and Settler Violence During the Gilded Age and Progressive Era John R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time Line of the Progressive Era from the Idea of America™

Time Line of The Progressive Era From The Idea of America™ Date Event Description March 3, Pennsylvania Mine Following an 1869 fire in an Avondale mine that kills 110 1870 Safety Act of 1870 workers, Pennsylvania passes the country's first coal mine safety passed law, mandating that mines have an emergency exit and ventilation. November Woman’s Christian Barred from traditional politics, groups such as the Woman’s 1874 Temperance Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) allow women a public Union founded platform to participate in issues of the day. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, the WCTU supports a national Prohibition political party and, by 1890, counts 150,000 members. February 4, Interstate The Interstate Commerce Act creates the Interstate Commerce 1887 Commerce act Commission to address price-fixing in the railroad industry. The passed Act is amended over the years to monitor new forms of interstate transportation, such as buses and trucks. September Hull House opens Jane Addams establishes Hull House in Chicago as a 1889 in Chicago “settlement house” for the needy. Addams and her colleagues, such as Florence Kelley, dedicate themselves to safe housing in the inner city, and call on lawmakers to bring about reforms: ending child labor, instituting better factory working conditions, and compulsory education. In 1931, Addams is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. November “White Caps” Led by Juan Jose Herrerra, the “White Caps” (Las Gorras 1889 released from Blancas) protest big business’s monopolization of land and prison resources in the New Mexico territory by destroying cattlemen’s fences. The group’s leaders gain popular support upon their release from prison in 1889. -

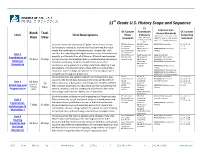

11 Grade U.S. History Scope and Sequence

th 11 Grade U.S. History Scope and Sequence C3 Common Core DC Content Framework DC Content Block Trad. Literacy Standards Unit Unit Descriptions Power Indicators RH.11-12.1, 11-12.2, 11-12.10 Supporting Days Days Standards D3.1, D4.3 and WHST.11-12.4, 11-12.5, 11-12.9 Standards D4.6 apply to each and 11-12.10 apply to each unit. unit. Students review the content of 8th grade United States History 11.1.6: Influences D1.4: Emerging RH.11-12.4: Vocabulary 11.1.1-11.1.5 on American questions 11.1.8 (colonization, revolution, and civil war) by examining the major Revolution D4.2: Construct WHST.11-12.2: Explanatory 11.1.10 trends from colonialism to Reconstruction. In particular, they 11.1.7: Formation explanations Writing of Constitution Unit 1 consider the expanding role of government, issues of freedom and 11.1.9: Effects of Apply to each unit: Apply to each unit: Foundations of equality, and the definition of citizenship. Students read complex Civil War and D3.1: Sources RH.11-12.1: Cite evidence 10 days 20 days primary sources, summarizing based on evidence while developing Reconstruction D4.3: Present RH.11-12.2: Central idea American historical vocabulary. Students should communicate their information RH.11-12.10: Comprehension D4.6: Analyze Democracy conclusions using explanatory writing, potentially adapting these problems WHST.11-12.4: Appropriate explanations into other formats to share within or outside their writing classroom. Students begin to examine the relationship between WHST.11-12.5: Writing process WHST.11-12.9: Using evidence compelling and supporting questions. -

American History 1 SSTH 033 061 Credits: 0.5 Units / 5 Hours / NCAA

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA HIGH SCHOOL American History 1 SSTH 033 061 Credits: 0.5 units / 5 hours / NCAA Course Description This course discusses the development of America from the colonial era until the start of the twentieth century. This includes European exploration and the collision between different societies (including European, African, and Native American). The course also explores the formation of the American government and how democracy in the United States affected thought and culture. Students will also learn about the influences of the Enlightenment on different cultural groups, religion, political and philosophical writings. Finally, they will examine various reform efforts, the Civil War, and the effects of expansion, immigration, and urbanization on American society. Graded Assessments: 5 Unit Evaluations; 3 Projects; 3 Proctored Progress Tests; 5 Teacher Connect Activities Course Objectives When you have completed the materials in this course, you should be able to: 1. Identify the Native American societies that existed before 1492. 2. Explain the reasons for European exploration and colonization. 3. Describe the civilizations that existed in Africa during the Age of Exploration. 4. Explore how Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans interacted in colonial America. 5. Summarize the ideas of the Enlightenment and the Great Awakening. 6. Examine the reasons for the American Revolution. 7. Discuss how John Locke’s philosophy influenced the Declaration of Independence. 8. Understand how the American political system works. 9. Trace the development of American democracy from the colonial era through the Gilded Age. 10. Evaluate the development of agriculture in America from the colonial era through the Gilded Age. -

Roaring Twenties,”

1 THIS IS AN OPTIONAL ENRICHMENT ASSIGNMENT. PRINT AND COMPLETE IN INK. Name:________________________________________ Class Period:_____ The Modern Era of the “Roaring Twenties,” Reading Assignment: Chapter 23 in AMSCO or other resource covering the 1920s. Mastery of the course and AP exam await all who choose to process the information as they read/receive. This is an optional assignment. So… young Jedi… what is your choice? Do? Or do not? There is no try. Pictured at left: Al Capone, Louis Armstrong, Flappers, John Scopes, Babe Ruth, public domain photos, WikiCommons) Directions: 1. Pre-Read: Read the prompts/questions within this guide before you read the chapter. 2. Skim: Flip through the chapter and note titles and subtitles. Look at images and read captions. Get a feel for the content you are about to read. 3. Read/Analyze: Read the chapter. If you have your own copy of AMSCO, Highlight key events and people as you read. Remember, the goal is not to “fish” for a specific answer(s) to reading guide questions, but to consider questions in order to critically understand what you read! 4. Write: Write (do not type) your notes and analysis in the spaces provided. Complete it in INK! Learning Goals: Defend or refute the following statement: The American economy and way of life dramatically changed during the 1920s as consumerism became the new American ideal. Identify and evaluate specific ways the culture of modernism in science, the arts, and entertainment conflicted with religious fundamentalism, nativism, and Prohibition. To what extent did the 1920s witness economic, social, and political gains for African Americans and women? To what extent did these years “roar?” To what extent was American foreign policy in the 1920s isolationist? Key Concepts FOR PERIOD 7: Key Concept 7.1: Growth expanded opportunity, while economic instability led to new efforts to reform U.S. -

U.S. History Objectives

U.S. History Objectives Unit 1 An Age of Prosperity and Corruption Students will understand the internal growth of the United States during the period of 1850s-1900. • Identify the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Compare and contrast politics of the Gilded Age and today’s governmental systems. • Describe how immigration was changing the social landscape of the United States resulting in the need for reform. Analyze and interpret maps, tables, and charts. Identify key terms. The Expansion of American Industry 1850-1920 Students will understand the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Identify the conditions that led to Industrial expansion. • Describe the technological revolution and the impact of the railroads and inventions. • Explain the growth of labor unions and the methods used by workers to achieve reform. Politics, 1870-1915 Students will understand the changes in cities and politics during the period known as the Gilded Age. • Compare and contrast politics of the Gilded Age and today’s governmental systems. • Be able to communicate why American cities experienced rapid growth. • Summarize the growth of Big Business and the role of monopolies. Immigration and Urban Life, 1870-1915 Students will understand the impact of immigration on the social landscape of the United States. • Analyze and interpret maps, tables, and charts. • Identify key terms. Give examples of how immigration was changing the social landscape of the United States. Relate the reasons for reform and the impact of the social movement. Unit 2 Internal and External Role of the United States Students will describe the changing internal and external roles of the United States between 1890- 1920. -

Teaching the Progressive Era Through the Life and Accomplishments of Jane Addams Kacy J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Teaching the Progressive Era through the life and accomplishments of Jane Addams Kacy J. Taylor Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Kacy J., "Teaching the Progressive Era through the life and accomplishments of Jane Addams" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 659. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/659 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING THE PROGRESSIVE ERA THROUGH THE LIFE AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF JANE ADDAMS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Kacy J. Taylor B.S. Louisiana State University, 1997 December 2005 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….iii Introduction……………………………………………………………………….………1 Chapter 1 Situating Jane Addams in American History…………………………………...8 2 From Religion to Spirituality………………………………………………….20 3 Spirituality Translates to Pragmatism…………………………………………35 4 Pragmatism -

How the National Guard Grew out of Progressive Era Reforms Matthew Am Rgis Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2016 America's Progressive Army: How the National Guard grew out of Progressive Era Reforms Matthew aM rgis Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Margis, Matthew, "America's Progressive Army: How the National Guard grew out of Progressive Era Reforms" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 15764. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/15764 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America’s progressive army: How the National Guard grew out of progressive era reforms by Matthew J. Margis A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural, Agricultural, Technological, Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Timothy Wolters, Major Professor Julie Courtwright Jeffrey Bremer Amy Bix John Monroe Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2016 Copyright © Matthew J. Margis, 2016. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my parents, and the loving memory of Anna Pattarozzi, -

The Politics of the Gilded Age

Unit 3 Class Notes- The Gilded Age The Politics of the Gilded Age The term “Gilded Age” was coined by Mark Twain in 1873 to describe the era in America following the Civil War; an era that from the outside looked to be a fantastic growth of wealth, power, opportunity, and technology. But under its gilded (plated in gold) surface, the second half of the nineteenth century contained a rotten core. In politics, business, labor, technology, agriculture, our continued conflict with Native Americans, immigration, and urbanization, the “Gilded Age” brought out the best and worst of the American experiment. While our nation’s population continued to grow, its civic health did not keep pace. The Civil War and Reconstruction led to waste, extravagance, speculation, and graft. The power of politicians and their political parties grew in direct proportion to their corruption. The Emergence of Political Machines- As cities experienced rapid urbanization, they were hampered by inefficient government. Political parties organized a new power structure to coordinate activities in cities. *** British historian James Bryce described late nineteenth-century municipal government as “the one conspicuous failure of the United States.” Political machines were the organized structure that controlled the activities of a political party in a city. o City Boss: . Controlled the political party throughout the city . Controlled access to city jobs and business licenses Example: Roscoe Conkling, New York City o Built parks, sewer systems, and water works o Provided money for schools hospitals, and orphanages o Ward Boss: . Worked to secure the vote in all precincts in a district . Helped gain the vote of the poor by provided services and doing favors Focused help for immigrants to o Gain citizenship o Find housing o Get jobs o Local Precinct Workers: . -

The Progressive Movement for the Recall, 1890S-1920

Published in: The New England Journal of History Winter, 2001, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 59-83 Power To The People: The Progressive Movement for the Recall, 1890s-1920 Rod Farmer Rod Farmer, Ph.D. Franklin Hall 252 Main St. University of Maine at Farmington Farmington, Maine 04938 Phone: (207) 778-7161 (office) (207) 778-9298 (home) Email: [email protected] Fax: 207 778-7157 Historian Warren Susman said of the people of the United States that: “The American is most characteristically a reformer and his history a series of reforms.” Susman saw “an almost continual impulse to reform from the days of the first English settlers on this continent who 1 proposed from the start nothing less than.....the establishment of the Kingdom of God.” Each generation of Americans has had its particular collection of reform efforts. That period known as the Progressive Era, from the 1890s to around 1920, brought a great change to American life by implanting in the nation the idea that government should be more proactive in solving economic and social problems and more responsible for creating a just and humane society. However, for most progressives, this enlarged government was also to be a more democratic government, because only a more democratic government could be trusted with the new powers and responsibilities. Historian Arthur S. Link found that, beginning in the 1890s, there “were many progressive movements on many levels seeking sometimes contradictory objectives” and that “despite its actual diversity and inner tensions it did seem to have unity; that is, it seemed to share 2 common ideals and objectives.” This paper will hold that the democratic ideal was one of those common ideals shared by most progressives, and this ideal can be identified in the crusade for the recall. -

Progressive Era: the Roaring Twenties

Name: _________________________________________ Date: __________ Period: __________ Directions: Close read and annotation. Before reading, take note of the items you should be looking for in the text and how they should be annotated. 1. Underline or highlight and annotate with an A the following: Evidence of where advertising helped create the idea of what life should be like. 2. Underline or highlight and annotate which B D the following: Which of the following sentences from the article BEST demonstrates the idea that A merica stood at a crossroads between advancement and tradition. 3. Determine what the central idea of the article is and write it here: 4. Underline or highlight and annotate with a C I the following: S entences that help to develop the CENTRAL idea of the article? Progressive Era: The Roaring Twenties By Joshua Zeitz, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, adapted by Newsela staff 12/14/2016 TOP: Russell Patterson's "Where There's Smoke There's Fire," showing a fashionably dressed woman of the time, often called a flapper, was painted around 1925. Courtesy of Library of Congress. BOTTOM: Calvin Coolidge in the late 1910s. The 1920s heralded a dramatic break between America’s past and future. Before World War I (1914-1918), the country remained culturally and psychologically rooted in the past. In the 1920s, America seemed to usher in a more modern era. The most vivid impressions of the 1920s are of flappers, movie palaces, radio empires, and Prohibition, the nationwide ban on alcohol that led to people making alcohol and drinking it in secret. -

Wonder Drug Or Bad Medicine? a Short History of Healthcare Reform and a Prognosis for Its Future Robert Saldin Politics Department Lecture January 31, 2011

Wonder Drug or Bad Medicine? A Short History of Healthcare Reform and a Prognosis for Its Future Robert Saldin Politics Department Lecture January 31, 2011 Robert Saldin is a Robert Wood Johnson Scholar at Harvard University and Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Montana he Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—more commonly known as simply the Affordable T Care Act or (at least by some) Obamacare—is a big deal. You may recall Vice President Joe Biden making the same point at the bill’s signing ceremony with slightly more colorful language. Well, he was right. The Affordable Care Act is a milestone in the broad scope of American healthcare policy. Among other things, it’s another step toward the longstanding liberal dream of universal coverage. To be sure, the new law does not get all the way to that promised land, but it’s an unmistakable step in that direction. The new law is also a big deal politically. It played a pivotal role in the Republicans’ historic victory in last fall’s midterm elections. And looking forward, you can expect a lot more discussion of healthcare in the next few years—including in the 2012 presidential campaign. Tonight, I’ll offer some thoughts on the political context of the new healthcare law. What does it mean in the broad, historic scope of American healthcare policy? And what does it mean for American politics right now and looking ahead to the 2012 elections? THE CURRENT STATE OF AMERICAN POLITICS Before diving into the healthcare debate, though, it’s worth taking a moment to assess where we are in American politics. -

Native American Land Cessions, 1867-1890: an Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources David Evensen St

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United American History Lesson Plans States 1-8-2016 Native American Land Cessions, 1867-1890: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources David Evensen St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/gilded_age Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Evensen, David, "Native American Land Cessions, 1867-1890: An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources" (2016). Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United States. 4. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/gilded_age/4 This lesson is brought to you for free and open access by the American History Lesson Plans at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Curriculum Unit on the Gilded Age in the United States by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Annotated Bibliography of Selected Sources in the Gilded Age, 1877-1900 by Dave Evensen Primary Sources: Bureau of Indian Affairs, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, RG 75: McLaughlin’s Report, December 15, 1890, accessed November 11, 2015, http://www.archives.gov/global-pages/larger- image.html?i=/publications/prologue/2008/fall/images/gall-report- l.jpg&c=/publications/prologue/2008/fall/images/gall-report.caption.html This source is the report Indian Agent McLaughlin completed describing the casualties of Native Americans in a confrontation on December 15, 1890. This document includes a list of police force causalities. The names are listed using an English name and Native American name.