Libby Larsen's Love After 1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalog 2008-2009

S w e et B riar College Catalog 2008-2009 2008-2009 College Calendar Fall Semester 2008 August 23, 2008 ____________________________________________ New students arrive August 27, 2008 __________________________________________ Opening Convocation August 28, 2008 _________________________________________________ Classes begin September 26, 2008 _____________________________________________ Founders’ Day September 25-27, 2008 ___________________________________Homecoming Weekend October 2-3, 2008 ________________________________________________ Reading Days October 17-19, 2008 __________________________________________ Families Weekend November 5, 2008 _____________________________ Registration for Spring Term Begins November 21, 2008 _________________________Thanksgiving vacation begins, 5:30 p.m. (Residence Halls close November 22 at 8 a.m.) December 1, 2008_______________________________________________ Classes resume December 12, 2008________________________________________________ Classes End December 13, 2008________________________________________________Reading Day December 14-19, 2008 ____________________________________________ Examinations December 19, 2008_________________________________ Winter break begins, 5:30 p.m. (Residence Halls close December 19 at 5:30 p.m.) Spring Semester 2009 January 21, 2009 ___________________________________________ Spring Term begins March 13, 2009 __________________________________ Spring vacation begins, 5:30 p.m. (Residence Halls close March 14 at 8 a.m.) March 23, 2009 _________________________________________________ -

The 6Th Annual Louisiana Studies Conference

1 The 6th Annual Louisiana Studies Conference Conference Keynote Speaker: Barry Ancelet, Professor and Granger & Debaillon Endowed Professor in Francophone Studies and Head, Department of Modern Languages, University of Louisiana at Lafayette Conference Keynote Roundtable: Moderator: Julie Kane, Professor of English, Northwestern State University, Louisiana Poet Laureate, 2011-2013 Participants: Darrell Bourque, Professor Emeritus, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Poet Laureate of Louisiana, 2009-2011 Clayton Delery-Edwards, Director of Academic Services, Louisiana School for Math, Science, and the Arts Gina Ferrara, Instructor of English, Delgado Community College Mona Lisa Saloy, Professor of English and Folklore, Dillard University Conference Co-Chairs: Lisa Abney, Vice President of Academic and Student Affairs, and Professor of English, Northwestern State University Jason Church, Materials Conservator, National Center for Preservation Technology and Training Shane Rasmussen, Director of the Louisiana Folklife Center and Associate Professor of English, Northwestern State University Conference Programming: Jason Church Shane Rasmussen Conference Hosts: Leslie Gruesbeck, Assistant Professor of Art and Gallery Director, Northwestern State University Greg Handel, Acting Director of the School of Creative and Performing Arts and Associate Professor of Music, Northwestern State University Selection Committees: NSU Louisiana High School Essay Contest: Shane Rasmussen, Chair Jason Church 2 Sarah McFarland, Director of Graduate Studies -

89241 Electronic KB Guts

57776 EKM Guts: 11/16/09 2:28 PM Page 1 E-Z PLAY® TODAY . .2 Beginnings for Piano . .2 Exploring Series . .3 Kid’s Keyboard Course . .3 Getting Started . .3 CD Play-Along . .4 Songbooks . .5 Stickers & Guides . .28 EASY ELECTRONIC KEYBOARD MUSIC (EKM) . .29 Instruction . .29 Songbooks . .30 ELECTRONIC KEYBOARD INSTRUCTION . .32 Starter Kits . .32 3 CHORD SONGBOOKS . .33 E-Z PLAY® TODAY STYLE INDEX . .34 ALPHA INDEX . .37 ORDERING INFORMATION . .40 © 2010 Hal Leonard Corporation Disney characters and artwork © Disney Enterprises, Inc. Prices are listed in U.S. dollars. Prices, contents, and availability subject to change without notice. 57776 EKM Guts: 11/16/09 2:28 PM Page 2 2 E-Z PLAY® TODAY BEGINNINGS – BEGINNINGS – BOOK C BOOK A Explains how to improvise E-Z Play Today ar rangements. 12 An introduction to the E-Z Play songs: All Through the Night • Amazing Grace • An dantino Today Music Series with easy • Dark Eyes • Fascination • Give My Regards to Broad way • instruction and 13 great songs, and more! including: When the Saints Go _______00100318 ...................................................$6.95 Marching In • Kumbaya • Beautiful Brown Eyes • BEGINNINGS SUPPLEMENTARY SONGBOOK ® Londonderry Air • I Gave My Love This supplementary songbook works with instruction books The E-Z PLAY TODAY songbook series is the a Cherry • and more. Also A, B, and C in BEGINNINGS FOR KEYBOARDS. Includes 28 shortest distance between beginning music and includes Keyboard Guides and Pedal Labels. super songs, including: Crazy • Edelweiss • Memory • Stand -

How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed. Julie Ellen Kane Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kane, Julie Ellen, "How the Villanelle's Form Got Fixed." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6892. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6892 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been rqxroduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directfy firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice, vdiile others may be from any typ e o f com pater printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^innm g at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Sarah Mclachlan Solace Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sarah McLachlan Solace mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Solace Country: Canada Released: 1995 Style: Folk Rock, Soft Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1696 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1164 mb WMA version RAR size: 1780 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 534 Other Formats: AAC ADX MPC VQF MMF DTS VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Drawn To The Rhythm Acoustic Guitar, Performer [Billatron] – Bill DillonBass – Daryl ExniciousDrums – Ronald 1 4:08 JonesKeyboards – Pierre MarchandMixed By – Pat MacCarthy*, Pierre MarchandVocals – Sarah McLachlan Into The Fire 2 Bass – Daryl ExniciousDrums – Paul BrennanOrgan, Keyboards, Guitar [Electric] – Pierre 3:34 MarchandVocals – Sarah McLachlanWritten-By – Pierre Marchand, Sarah McLachlan The Path Of Thorns (Terms) Acoustic Guitar, Guitar [Electric] – Bill DillonAcoustic Guitar, Vocals – Sarah 3 5:51 McLachlanBass – Daryl ExniciousDrums, Tambourine – Ronald JonesOrgan – Pierre Marchand I Will Not Forget You Acoustic Guitar, Guitar [Electric] – Bill DillonBass, Percussion, Keyboards – Pierre 4 5:20 MarchandDrums – Ash Sood*Lyrics By – Sarah McLachlanMusic By – Darren Phillips, Sarah McLachlanPercussion – Michel DupirreVocals, Piano – Sarah McLachlan Lost Acoustic Guitar, Piano, Vocals – Sarah McLachlanBacking Vocals – Daryl ExniciousBass – 5 4:03 Hugh MacMillanDrums – Ronald JonesGuitar [Pedal Steel], Guitar [12-string], Mandolin – Bill DillonPercussion, Keyboards – Pierre Marchand Back Door Man Acoustic Guitar, Guitar [Electric], Guitar [Guitorgan] – Bill DillonBass – Daryl Exnicious, 6 4:00 Hugh MacMillanDrums -

Refrain, Again: the Return of the Villanelle

Refrain, Again: The Return of the Villanelle Amanda Lowry French Charlottesville, VA B.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 1992, cum laude M.A., Concentration in Women's Studies, University of Virginia, 1995 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia August 2004 ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ABSTRACT Poets and scholars are all wrong about the villanelle. While most reference texts teach that the villanelle's nineteen-line alternating-refrain form was codified in the Renaissance, the scholar Julie Kane has conclusively shown that Jean Passerat's "Villanelle" ("J'ay perdu ma Tourterelle"), written in 1574 and first published in 1606, is the only Renaissance example of this form. My own research has discovered that the nineteenth-century "revival" of the villanelle stems from an 1844 treatise by a little- known French Romantic poet-critic named Wilhelm Ténint. My study traces the villanelle first from its highly mythologized origin in the humanism of Renaissance France to its deployment in French post-Romantic and English Parnassian and Decadent verse, then from its bare survival in the period of high modernism to its minor revival by mid-century modernists, concluding with its prominence in the polyvocal culture wars of Anglophone poetry ever since Elizabeth Bishop’s "One Art" (1976). The villanelle might justly be called the only fixed form of contemporary invention in English; contemporary poets may be attracted to the form because it connotes tradition without bearing the burden of tradition. Poets and scholars have neither wanted nor needed to know that the villanelle is not an archaic, foreign form. -

In Music, University of London Institute of Education 1987

TOWARDSA MODELOF THE DEVELOPMENTOF MUSICAL CREATIVITY: A STUDYOF THE COMPOSITIONSOF CHILDREN AGED 3- 11 by June Barbara TILLMAN Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music, University of London Institute of Education 1987 uý y UNI V, 1 I ABSTRACT The first part is concerned with the literature. The first chapter deals with the problem of definition and is a general outline of all the issues, many of which will be discussed in more detail later. The second including examines the positions taken by a wide variety of writers psych- ologists, psychiatrists and artists themselves on the subject of the creative In it process and in particular whether it can be divided into stages. In the there is a greater concern with creativity in the arts in general. third the writings on the creative process are linked with those about child- fourth ren's creativity and in particular their musical work. The chapter examines the history of the relationship between creativity and education and draws on the preceding chapters to set out some of the educational implications. the The second part turns to a survey of children's compositions and based the development of an eight-stage spiral of development. This is on psychological concepts of mastery, imitation, imaginative play and meta- cognition and on an interpretation of hundreds of children's compositions. the (The age range is 3 to 11). The second chapter links this spiral with preceding chapters on creativity. the The last chapter outlines the implications for various aspects of curriculum and possible wider implications. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76695-1 - The Cambridge Companion to American Poetry since 1945 Edited by Jennifer Ashton Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to American Poetry since 1945 The extent to which American poetry reinvented itself after World War II is a testament to the changing social, political, and economic landscape of twentieth- century American life. Registering an important shift in the way scholars contextualize modern and contemporary American literature, this Companion explores how American poetry has documented and, at times, helped propel the literary and cultural revolutions of the past sixty-five years. Offering authoritative and accessible essays from fourteen distinguished scholars, the Companion sheds new light on the Beat, Black Arts, and other movements while examining institutions that govern poetic practice in the United States today. The text also introduces seminal figures like Sylvia Plath, John Ashbery, and Gwendolyn Brooks while situating them alongside phenomena such as the “academic poet” and popular forms such as spoken word and rap, revealing the breadth of their shared history. Students, scholars, and readers will find this Companion an indispensable guide to postwar and late-twentieth-century American poetry. Jennifer Ashton is Associate Professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where she teaches literary theory and the history of poetry. She is author of From Modernism to Postmodernism: American Poetry and Theory in the Twentieth Century and has published articles in Modernism/Modernity, Modern Philology, American Literary History, and Western Humanities Review. A complete list of books in the series is at the back of this book. -

Hit Sheet 83

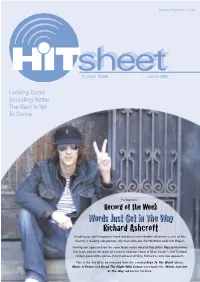

www.hitsheet.co.uk 7 JULY 2006 ISSUE #85 Looking Good, Sounding Better... The Best Is Yet To Come Parlophone Record of the Week WordsWords JustJust GetGet inin TheThe WayWay Richard Ashcroft Heading up our Parlophone front and back cover double whammy is one of this country’s leading songwriters, the man who put the Northern soul into Wigan. Having just appeared on the soon to be much missed Top of the Pops performing this track and on the back of a recent sold out show at Manchester’s Old Trafford cricket ground the genius (not madness) of King Richard is only too apparent. This is the 3rd hit to be released from the seminal Keys To The World album. Music Is Power and Break The Night With Colour were both hits, Words Just Get In The Way will be the hat-trick. 2 Hello and welcome to issue #85 of the Hit Sheet! So bird flu developed into world cup fever and we’re now left and should make her the superstar she deserves to be. as sick as parrots. If you look at my editorial last month I Meeting her afterwards was also a thrill as she was both predicted that England would lose on penalties in the quarter gorgeous and friendly! 31 The Birches, London, N21 1NJ finals and that Wayne Rooney would be sent off, so I wasn’t Finally, the Who gig in Hyde Park was fantastic, Pete too surprised. In my opinion England were doomed as soon Townshend’s guitar playing was an inspiration to all. -

Song List - Sorted by Song

Last Update 2/10/2007 Encore Entertainment PO Box 1218, Groton, MA 01450-3218 800-424-6522 [email protected] www.encoresound.com Song List - Sorted By Song SONG ARTIST ALBUM FORMAT #1 Nelly Nellyville CD #34 Matthews, Dave Dave Matthews - Under The Table And Dreamin CD #9 Dream Lennon, John John Lennon Collection CD (Every Time I Hear)That Mellow Saxophone Setzer Brian Swing This Baby CD (Sittin' On)The Dock Of The Bay Bolton, Michael The Hunger CD (You Make Me Feel Like A) Natural Woman Clarkson, Kelly American Idol - Greatest Moments CD 1 Thing Amerie NOW 19 CD 1, 2 Step Ciara (featuring Missy Elliott) Totally Hits 2005 CD 1,2,3 Estefan, Gloria Gloria Estafan - Greatest Hits CD 100 Years Blues Traveler Blues Traveler CD 100 Years Five For Fighting NOW 15 CD 100% Pure Love Waters, Crystal Dance Mix USA Vol.3 CD 11 Months And 29 Days Paycheck, Johnny Johnny Paycheck - Biggest Hits CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len Billboard Rock 'N' Roll Hits 1965 CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len More 60s Jukebox Favorites CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len Vintage Music 7 & 8 CD 14 Years Guns 'N' Roses Use Your Illusion II CD 16 Candles Crests, The Billboard Rock 'N' Roll Hits 1959 CD 16 Candles Crests, The Lovin' Fifties CD 16 Horses Soul Coughing X-Files - Soundtrack CD 18 Wheeler Pink Pink - Missundaztood CD 19 Paul Hardcastle Living In Oblivion Vol.1 CD 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1997 Grammy Nominees CD 1982 Travis, Randy Country Jukebox CD 1982 Travis, Randy Randy Travis - Greatest Hits Vol.1 CD 1985 Bowlling For Soup NOW 17 CD 1990 Medley Mix Abdul, Paula Shut Up And Dance CD 1999 Prince -

Sombres Dimanches Une Étude En Noir

Michael Fingerhut Gloomy Sundays : A Study In Black mardi 19 mai 1998 Sombres Dimanches Une étude en noir Michel Fingerhut 19/05/1998 1 of 15 Michael Fingerhut Gloomy Sundays : A Study In Black mardi 19 mai 1998 Overture To Death D.P. MacDonald [Supposedly from] The Cincinatti Journal of Ceremonial Magick, vol. 1, no. 1, 1976 In February of 1936, Budapest Police were investigating the suicide of a local shoemaker, Joseph Keller. The investigation showed that Keller had left a suicide note in which he quoted the lyrics of a recent popular song. The song was "Gloomy Sunday". The fact that a man chose to quote the lyrics of a little-known song may not seem very strange. However, the fact that over the years, this song has been directly associated with the death of over 100 people is quite strange indeed. Following the event described above, seventeen additional people took their own lives. In each case, "Gloomy Sunday" was closely connected with the circumstances surrounding the suicide. Among those included are two people who shot themselves while listening to a gypsy band playing the tune. Several others drowned themselves in the Danube while clutching the sheet music of "Gloomy Sunday". One gentleman reportedly walked out of a nightclub and blew his brains out after having requested the band to play "The Suicide Song". The adverse effect of "Gloomy Sunday" was becoming so great that the Budapest Police thought it best to ban the song. However, the suppression of "Gloomy Sunday" was not restricted to Budapest, nor was its seemingly evil effects. -

A Rhythmic Analysis of Rap - What Can We Learn from ‘Flow’?

A Rhythmic Analysis of Rap - What can we learn from ‘flow’? A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Linguistics in the University of Canterbury by Iskandar Rhys Davis March 2017 Contents Chapter I: Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose and goals of investigating rap rhythm ........................................................... 1 1.2 Hip-Hop roots .............................................................................................................. 2 1.2.1 MCs and DJs ........................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Where rap began .................................................................................................. 3 1.2.3 Progression of rap content ................................................................................... 4 1.2.4 The use of sampling ............................................................................................. 6 1.3 An introduction to flow ............................................................................................... 7 1.4 Rap arenas and their influence on rap style............................................................... 10 1.4.1 Different rap forms ............................................................................................ 11 1.4.2 The mainstream vs. underground debate ..........................................................