In Music, University of London Institute of Education 1987

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

89241 Electronic KB Guts

57776 EKM Guts: 11/16/09 2:28 PM Page 1 E-Z PLAY® TODAY . .2 Beginnings for Piano . .2 Exploring Series . .3 Kid’s Keyboard Course . .3 Getting Started . .3 CD Play-Along . .4 Songbooks . .5 Stickers & Guides . .28 EASY ELECTRONIC KEYBOARD MUSIC (EKM) . .29 Instruction . .29 Songbooks . .30 ELECTRONIC KEYBOARD INSTRUCTION . .32 Starter Kits . .32 3 CHORD SONGBOOKS . .33 E-Z PLAY® TODAY STYLE INDEX . .34 ALPHA INDEX . .37 ORDERING INFORMATION . .40 © 2010 Hal Leonard Corporation Disney characters and artwork © Disney Enterprises, Inc. Prices are listed in U.S. dollars. Prices, contents, and availability subject to change without notice. 57776 EKM Guts: 11/16/09 2:28 PM Page 2 2 E-Z PLAY® TODAY BEGINNINGS – BEGINNINGS – BOOK C BOOK A Explains how to improvise E-Z Play Today ar rangements. 12 An introduction to the E-Z Play songs: All Through the Night • Amazing Grace • An dantino Today Music Series with easy • Dark Eyes • Fascination • Give My Regards to Broad way • instruction and 13 great songs, and more! including: When the Saints Go _______00100318 ...................................................$6.95 Marching In • Kumbaya • Beautiful Brown Eyes • BEGINNINGS SUPPLEMENTARY SONGBOOK ® Londonderry Air • I Gave My Love This supplementary songbook works with instruction books The E-Z PLAY TODAY songbook series is the a Cherry • and more. Also A, B, and C in BEGINNINGS FOR KEYBOARDS. Includes 28 shortest distance between beginning music and includes Keyboard Guides and Pedal Labels. super songs, including: Crazy • Edelweiss • Memory • Stand -

Sarah Mclachlan Solace Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sarah McLachlan Solace mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Solace Country: Canada Released: 1995 Style: Folk Rock, Soft Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1696 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1164 mb WMA version RAR size: 1780 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 534 Other Formats: AAC ADX MPC VQF MMF DTS VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Drawn To The Rhythm Acoustic Guitar, Performer [Billatron] – Bill DillonBass – Daryl ExniciousDrums – Ronald 1 4:08 JonesKeyboards – Pierre MarchandMixed By – Pat MacCarthy*, Pierre MarchandVocals – Sarah McLachlan Into The Fire 2 Bass – Daryl ExniciousDrums – Paul BrennanOrgan, Keyboards, Guitar [Electric] – Pierre 3:34 MarchandVocals – Sarah McLachlanWritten-By – Pierre Marchand, Sarah McLachlan The Path Of Thorns (Terms) Acoustic Guitar, Guitar [Electric] – Bill DillonAcoustic Guitar, Vocals – Sarah 3 5:51 McLachlanBass – Daryl ExniciousDrums, Tambourine – Ronald JonesOrgan – Pierre Marchand I Will Not Forget You Acoustic Guitar, Guitar [Electric] – Bill DillonBass, Percussion, Keyboards – Pierre 4 5:20 MarchandDrums – Ash Sood*Lyrics By – Sarah McLachlanMusic By – Darren Phillips, Sarah McLachlanPercussion – Michel DupirreVocals, Piano – Sarah McLachlan Lost Acoustic Guitar, Piano, Vocals – Sarah McLachlanBacking Vocals – Daryl ExniciousBass – 5 4:03 Hugh MacMillanDrums – Ronald JonesGuitar [Pedal Steel], Guitar [12-string], Mandolin – Bill DillonPercussion, Keyboards – Pierre Marchand Back Door Man Acoustic Guitar, Guitar [Electric], Guitar [Guitorgan] – Bill DillonBass – Daryl Exnicious, 6 4:00 Hugh MacMillanDrums -

Hit Sheet 83

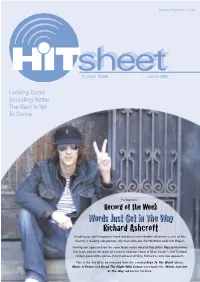

www.hitsheet.co.uk 7 JULY 2006 ISSUE #85 Looking Good, Sounding Better... The Best Is Yet To Come Parlophone Record of the Week WordsWords JustJust GetGet inin TheThe WayWay Richard Ashcroft Heading up our Parlophone front and back cover double whammy is one of this country’s leading songwriters, the man who put the Northern soul into Wigan. Having just appeared on the soon to be much missed Top of the Pops performing this track and on the back of a recent sold out show at Manchester’s Old Trafford cricket ground the genius (not madness) of King Richard is only too apparent. This is the 3rd hit to be released from the seminal Keys To The World album. Music Is Power and Break The Night With Colour were both hits, Words Just Get In The Way will be the hat-trick. 2 Hello and welcome to issue #85 of the Hit Sheet! So bird flu developed into world cup fever and we’re now left and should make her the superstar she deserves to be. as sick as parrots. If you look at my editorial last month I Meeting her afterwards was also a thrill as she was both predicted that England would lose on penalties in the quarter gorgeous and friendly! 31 The Birches, London, N21 1NJ finals and that Wayne Rooney would be sent off, so I wasn’t Finally, the Who gig in Hyde Park was fantastic, Pete too surprised. In my opinion England were doomed as soon Townshend’s guitar playing was an inspiration to all. -

Song List - Sorted by Song

Last Update 2/10/2007 Encore Entertainment PO Box 1218, Groton, MA 01450-3218 800-424-6522 [email protected] www.encoresound.com Song List - Sorted By Song SONG ARTIST ALBUM FORMAT #1 Nelly Nellyville CD #34 Matthews, Dave Dave Matthews - Under The Table And Dreamin CD #9 Dream Lennon, John John Lennon Collection CD (Every Time I Hear)That Mellow Saxophone Setzer Brian Swing This Baby CD (Sittin' On)The Dock Of The Bay Bolton, Michael The Hunger CD (You Make Me Feel Like A) Natural Woman Clarkson, Kelly American Idol - Greatest Moments CD 1 Thing Amerie NOW 19 CD 1, 2 Step Ciara (featuring Missy Elliott) Totally Hits 2005 CD 1,2,3 Estefan, Gloria Gloria Estafan - Greatest Hits CD 100 Years Blues Traveler Blues Traveler CD 100 Years Five For Fighting NOW 15 CD 100% Pure Love Waters, Crystal Dance Mix USA Vol.3 CD 11 Months And 29 Days Paycheck, Johnny Johnny Paycheck - Biggest Hits CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len Billboard Rock 'N' Roll Hits 1965 CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len More 60s Jukebox Favorites CD 1-2-3 Barry, Len Vintage Music 7 & 8 CD 14 Years Guns 'N' Roses Use Your Illusion II CD 16 Candles Crests, The Billboard Rock 'N' Roll Hits 1959 CD 16 Candles Crests, The Lovin' Fifties CD 16 Horses Soul Coughing X-Files - Soundtrack CD 18 Wheeler Pink Pink - Missundaztood CD 19 Paul Hardcastle Living In Oblivion Vol.1 CD 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1997 Grammy Nominees CD 1982 Travis, Randy Country Jukebox CD 1982 Travis, Randy Randy Travis - Greatest Hits Vol.1 CD 1985 Bowlling For Soup NOW 17 CD 1990 Medley Mix Abdul, Paula Shut Up And Dance CD 1999 Prince -

Sombres Dimanches Une Étude En Noir

Michael Fingerhut Gloomy Sundays : A Study In Black mardi 19 mai 1998 Sombres Dimanches Une étude en noir Michel Fingerhut 19/05/1998 1 of 15 Michael Fingerhut Gloomy Sundays : A Study In Black mardi 19 mai 1998 Overture To Death D.P. MacDonald [Supposedly from] The Cincinatti Journal of Ceremonial Magick, vol. 1, no. 1, 1976 In February of 1936, Budapest Police were investigating the suicide of a local shoemaker, Joseph Keller. The investigation showed that Keller had left a suicide note in which he quoted the lyrics of a recent popular song. The song was "Gloomy Sunday". The fact that a man chose to quote the lyrics of a little-known song may not seem very strange. However, the fact that over the years, this song has been directly associated with the death of over 100 people is quite strange indeed. Following the event described above, seventeen additional people took their own lives. In each case, "Gloomy Sunday" was closely connected with the circumstances surrounding the suicide. Among those included are two people who shot themselves while listening to a gypsy band playing the tune. Several others drowned themselves in the Danube while clutching the sheet music of "Gloomy Sunday". One gentleman reportedly walked out of a nightclub and blew his brains out after having requested the band to play "The Suicide Song". The adverse effect of "Gloomy Sunday" was becoming so great that the Budapest Police thought it best to ban the song. However, the suppression of "Gloomy Sunday" was not restricted to Budapest, nor was its seemingly evil effects. -

A Rhythmic Analysis of Rap - What Can We Learn from ‘Flow’?

A Rhythmic Analysis of Rap - What can we learn from ‘flow’? A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Linguistics in the University of Canterbury by Iskandar Rhys Davis March 2017 Contents Chapter I: Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose and goals of investigating rap rhythm ........................................................... 1 1.2 Hip-Hop roots .............................................................................................................. 2 1.2.1 MCs and DJs ........................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Where rap began .................................................................................................. 3 1.2.3 Progression of rap content ................................................................................... 4 1.2.4 The use of sampling ............................................................................................. 6 1.3 An introduction to flow ............................................................................................... 7 1.4 Rap arenas and their influence on rap style............................................................... 10 1.4.1 Different rap forms ............................................................................................ 11 1.4.2 The mainstream vs. underground debate .......................................................... -

The Otaku Lifestyle: Examining Soundtracks in the Anime Canon

THE OTAKU LIFESTYLE: EXAMINING SOUNDTRACKS IN THE ANIME CANON A THESIS IN Musicology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC by MICHELLE JURKIEWICZ B.M., University of Central Missouri, 2014 Kansas City, Missouri 2019 © 2019 MICHELLE JURKIEWICZ ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE OTAKU LIFESTYLE: EXAMINING SOUNDTRACKS IN THE ANIME CANON Michelle Jurkiewicz, Candidate for the Master of Music Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2019 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, or anime, has been popular around the globe for the last sixty years. Anime has its own fan culture in the United States known as otaku, or the obsessive lifestyle surrounding manga and anime, which has resulted in American production companies creating their own “anime.” Japanese filmmakers do not regard anime simply as a cartoon, but instead realize it as genre of film, such as action or comedy. However, Japanese anime is not only dynamic and influential because of its storylines, characters, and themes, but also for its purposeful choices in music. Since the first anime Astro Boy and through films such as Akira, Japanese animation companies combine their history from the past century with modern or “westernized” music. Unlike cartoon films produced by Disney or Pixar, Japanese anime do not use music to mimic the actions on-screen; instead, music heightens and deepens the plot and emotions. This concept is practiced in live-action feature films, and although anime consists of hand-drawn and computer-generated cartoons, Japanese directors and animators create a “film” experience with their dramatic choice of music. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ To Happiness A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) in the Department of English and Comparative Literatures of the College of Arts & Sciences 2008 by Martha Elizabeth Tilton B.S., Miami University, 1979 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2002 Committee Chair: Don Bogen, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation contains a manuscript of original poetry and a critical paper. The forty- nine poems divide into three parts—the sections differ in time, perspective, and tone and yet an energetic and hospitable voice knits them. The critical paper utilizes trauma and cartographic theories through which it argues that the repetitive gestures and the repetitive gaps in knowledge in Paula Gunn Allen’s poems and essays constitute evidence of Native American cultural trauma. iii for Debbie, who’s so happy with surprises iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Grateful acknowledgment is due to the following publications in which some of these poems previously appeared: JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association: “A Circle Portrait” New Orleans Review: “Switches from the Fig Tree” Schuylkill Valley Journal: “Old Maids” Southern Humanities Review: “Bulldogging, 1924” Southern Review: “When the Movers Took the Bed” Valparaiso Poetry Review: “Alto” Thanks to my family: Debbie Fritz; Bonnie and Lawrence Tilton; Cameron, Courtney, Grayson Tilton and Zane Wilson. -

MTO 17.3: Attas, Defining Phrase in Popular Music

Volume 17, Number 3, October 2011 Copyright © 2011 Society for Music Theory Sarah Setting the Terms: Defining Phrase in Popular Music Robin Attas NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.3/mto.11.17.3.attas.php KEYWORDS: form, phrase, phrase rhythm, song structure, Sarah McLachlan, popular music analysis, functional introduction ABSTRACT: Studies of phrase rhythm in popular music often leave the definition of “phrase” implicit, and those scholars who do define the term often emphasize the role of breath, ignoring the many other musical features that help create a phrase. By defining a pop music phrase as a musical unit with goal-directed motion towards a clear conclusion, clear analysis of phrase rhythm and song structure becomes possible. Analyses of three songs by contemporary singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan demonstrate typical ways of creating phrases in popular music, and explore some common modifications to phrase rhythm and song structure that can be applied to the work of numerous other musicians. Received February 2011 [1] Over the past decade, there has been an explosion of music-theoretical work covering all aspects of popular music, including pitch, meter, form, and timbre. The subject of phrase rhythm, a familiar topic in music discourse due to countless studies in the art music repertoire, is no exception to this statement. Articles such as Neal 2007, Everett 2009b, and Zak 2010 explore phrase structures in the songs of specific artists (the Dixie Chicks with songwriter Darrell Scott, the Beatles, and Roy Orbison, respectively) and make worthy contributions not only to the understanding of this topic in popular music, but to the study of music more generally. -

Creating Style and Extending Boundaries: an Analysis of Three

University of Alberta Creating Style and Extending Boundaries: An Anaiysis of Three Women in Rock A thesis subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fiilfiIlment of the requiremems for the degree of Master of Music Musicology Department of Music Edmonton, Alberta Falf 1998 National Libraiy BiblioWque nationale m*m of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington Ortawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distniiuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts ikom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis is an anaiysis of the music of three women in rock music: Sarah Mchhlan, Shed Crow, and Sinead O'Connor. The discussion centers on how each of these artists has created a distinctive style, carving a particular niche in the popular music market in the 1990s. -

Variations on a Theme: Forty Years of Music, Memories, and Mistakes

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes Christopher John Stephens University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Stephens, Christopher John, "Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 934. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/934 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Creative Non-Fiction By Christopher John Stephens B.A., Salem State College, 1988 M.A., Salem State College, 1993 May 2009 DEDICATION For my parents, Jay A. Stephens (July 6, 1928-June 20, 1997) Ruth C. -

Libby Larsen's Love After 1950

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE LIBBY LARSEN’S LOVE AFTER 1950 A SONG CYCLE FOR MEZZO-SOPRANO AND PIANO A STYLISTIC AND INTERPRETIVE ANALYSIS A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By JANICE W. LOGAN Norman, Oklahoma 2008 LIBBY LARSEN’S LOVE AFTER 1950 A SONG CYCLE FOR MEZZO-SOPRANO AND PIANO: A STYLISTIC AND INTERPRETIVE ANALYSIS A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC © Copyright by JANICE W. LOGAN 2008 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document is dedicated to those who have so patiently encouraged me and guided me through this process. Dr. Wagner and Dr. Reichardt, especially, have been tireless in their response to help me in design and style of this document. Libby Larsen’s music is a joy to study, and she has inspired me by her approach to poetry, composition, womanhood, and full and expressive living. I also thank Dr. Diane Coloton for introducing me to this work. I thank Dr. Michael Lee for his fascinating classes and inspiring mind, Dr. Leffingwell for her love of music and singing, and Dr. Schlegel for his prompt responses and kind encouragement. My husband Earl has provided continued encouragement and support, technical assistance, and patience. Thanks to my special friend and technical lifeline, Jennifer Elbert, for her computer prowess. I am especially grateful for and blessed by the young women in my family, all music teachers, who demonstrate the highest level of musicianship, are dedicated teachers and performers, and continually amaze and inspire me with their maturity and grasp of womanhood: Christian Morren, Tracey Gregg- Boothby, Jenn Goodner, and Amy Logan.