Kiyou14 02.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report 11.2019

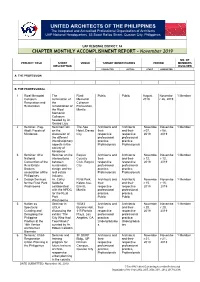

UNITED ARCHITECTS OF THE PHILIPPINES The Integrated and Accredited Professional Organization of Architects UAP National Headquarters, 53 Scout Rallos Street, Quezon City, Philippines UAP REGIONAL DISTRICT: A4 CHAPTER MONTHLY ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT – November 2019 NO. OF PROJECT TITLE SHORT VENUE TARGET BENEFICIARIES PERIOD MEMBERS DESCRIPTION INVOLVED PROJECTED ACTUAL START COMPLETED A. THE PROFESSION B. THE PROFESSIONAL 1 Rizal Memorial The Rizal Public Public August Novembe 1 Member Coliseum culmination of Memorial 2019 r 26, 2019 Renovation and the Coliseum Restoration rehabilitation of Renovation, the Rizal Manila Memorial Coliseum headed by Ar. Gerard Lico 2 Seminar- Pag- Seminar/Talk The Apo Architects and Architects Novembe Novembe 1 Member Aboll: Facets of on the Hotel, Davao their and their r 07, r 08, Mindanao discussion of City respective respective 2019 2019 the different professional professional interdisciplinary practice, practice, aspects in the Professionals Professionals society of Mindanao 3 Seminar: 41st Seminar on the Bagiuo Architects and Architects Novembe Novembe 1 Member National intersections Country their and their r 12, r 12, Convention of the between Club, Baguio respective respective 2019 2019 Real Estate sustainable City professional professional Brokers design and the practice, practice, association of the real estate Professionals Professionals Philippines industry. 4 Design Services Ar. Cathy Rizal Park, Architects and Architects Novembe Novembe 1 Member for the Rizal Park Saldaña Kalaw Ave, their and -

The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700-1706

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 41 Number 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 41, Article 7 Issue 1 1962 The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700-1706 Charles W. Arnade Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Arnade, Charles W. (1962) "The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700-1706," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 41 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol41/iss1/7 Arnade: The English Invasion of Spanish Florida, 1700-1706 THE ENGLISH INVASION OF SPANISH FLORIDA, 1700-1706 by CHARLES W. ARNADE HOUGH FLORIDA had been discovered by Ponce de Leon in T 1513, not until 1565 did it become a Spanish province in fact. In that year Pedro Menendez de Aviles was able to establish a permanent capital which he called St. Augustine. Menendez and successive executives had plans to make St. Augustine a thriving metropolis ruling over a vast Spanish colony that might possibly be elevated to a viceroyalty. Nothing of this sort happened. By 1599 Florida was in desperate straits: Indians had rebelled and butchered the Franciscan missionaries, fire and flood had made life in St. Augustine miserable, English pirates of such fame as Drake had ransacked the town, local jealousies made life unpleasant. -

Macrofouler Community Succession in South Harbor, Manila Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines During the Northeast Monsoon Season of 2017–2018

Philippine Journal of Science 148 (3): 441-456, September 2019 ISSN 0031 - 7683 Date Received: 26 Mar 2019 Macrofouler Community Succession in South Harbor, Manila Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines during the Northeast Monsoon Season of 2017–2018 Claire B. Trinidad1, Rafael Lorenzo G. Valenzuela1, Melody Anne B. Ocampo1, and Benjamin M. Vallejo, Jr.2,3* 1Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Manila, Padre Faura Street, Ermita, Manila 1000 Philippines 2Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology, College of Science, University of the Philippines Diliman, Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Philippines 3Science and Society Program, College of Science, University of the Philippines Diliman, Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Philippines Manila Bay is one of the most important bodies of water in the Philippines. Within it is the Port of Manila South Harbor, which receives international vessels that could carry non-indigenous macrofouling species. This study describes the species composition of the macrofouling community in South Harbor, Manila Bay during the northeast monsoon season. Nine fouler collectors designed by the North Pacific Marine Sciences Organization (PICES) were submerged in each of five sampling points in Manila Bay on 06 Oct 2017. Three collection plates from each of the five sites were retrieved every four weeks until 06 Feb 2018. Identification was done via morphological and CO1 gene analysis. A total of 18,830 organisms were classified into 17 families. For the first two months, Amphibalanus amphitrite was the most abundant taxon; in succeeding months, polychaetes became the most abundant. This shift in abundance was attributed to intraspecific competition within barnacles and the recruitment of polychaetes. -

Part Ii Metro Manila and Its 200Km Radius Sphere

PART II METRO MANILA AND ITS 200KM RADIUS SPHERE CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA 7.1 PHYSICAL PROFILE The area defined by a sphere of 200 km radius from Metro Manila is bordered on the northern part by portions of Region I and II, and for its greater part, by Region III. Region III, also known as the reconfigured Central Luzon Region due to the inclusion of the province of Aurora, has the largest contiguous lowland area in the country. Its total land area of 1.8 million hectares is 6.1 percent of the total land area in the country. Of all the regions in the country, it is closest to Metro Manila. The southern part of the sphere is bound by the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon, all of which comprise Region IV-A, also known as CALABARZON. 7.1.1 Geomorphological Units The prevailing landforms in Central Luzon can be described as a large basin surrounded by mountain ranges on three sides. On its northern boundary, the Caraballo and Sierra Madre mountain ranges separate it from the provinces of Pangasinan and Nueva Vizcaya. In the eastern section, the Sierra Madre mountain range traverses the length of Aurora, Nueva Ecija and Bulacan. The Zambales mountains separates the central plains from the urban areas of Zambales at the western side. The region’s major drainage networks discharge to Lingayen Gulf in the northwest, Manila Bay in the south, the Pacific Ocean in the east, and the China Sea in the west. -

The Manila Galleon and the Opening of the Trans-Pacific West

Old Pueblo Archaeology Center presents The Manila Galleon and the Opening of the Trans-Pacific West A free presentation by Father Greg Adolf for Old Pueblo Archaeology Center’s “Third Thursday Food for Thought” Dinner Program Thursday September 19, 2019, from 6 to 8:30 p.m. This month’s program will be at Karichimaka Mexican Restaurant, 5252 S. Mission Rd., Tucson MAKE YOUR RESERVATION WITH OLD PUEBLO ARCHAEOLOGY CENTER: 520-798-1201 or [email protected] RESERVATIONS MUST BE REQUESTED AND CONFIRMED before 5 p.m. on the Wednesday before the program. The first of the galleons crossed the Pacific in 1565. The last one put into port in 1815. Yearly, for the two and a half centuries that lay between, the galleons made the long and lonely voyage between Manila in the Philippines and Acapulco in Mexico. No other commercial enterprise has ever endured so long. No other regular navigation has been so challenging and dangerous as this, for in its two hundred and fifty years, the ocean claimed dozens of ships and thousands of lives, and many millions in treasure. To the peoples of Spanish America, they were the “China Ships” or “Manila Galleons” that brought them cargoes of silks and spices and other precious merchandise of the Orient, forever changing the material culture of the Spanish Americas. To those in the Orient, they were the “Silver Ships” laden with Mexican and Peruvian pesos that were to become the standard form of currency throughout the Orient. To the Californias and the Spanish settlements of the Pimería Alta in what is now Arizona and Sonora, they furnished the motive and drive to explore and populate the long California coastline. -

Expedition Conquistador Brochure

EXPEDITION CONQUISTADOR Traveling Exhibit Proposal The Palm Beach Museum of Natural History Minimum Requirements 500-3,500 sq. ft. (variable, based on available space) of display area 8-12 ft ceiling clearance Available for 6-8 week (or longer) periods Expedition Conquistador takes three to seven days to set up and take down Assistance by venue staff may be required to unload, set up and break down the exhibit Venue provides all set up/break down equipment, including pallet jacks, fork lift, etc. Structure of Exhibit Basic: Armored Conquistador Diorama – (3 foot soldiers or 1 mounted on horse, 120 sq. ft.) Maps and Maritime Navigation Display Weapons and Armor Display Trade in the New World Display Daily Life and Clothing Display American Indian Weaponry and material culture (contemporary 16th century) Optional: First Contact Diorama (explorers, foot soldiers, sailors, priests, American Indians) American Indian Habitation Diorama Living History Component Both the basic and optional versions of Expedition Conquistador can be adjusted via the modification of the number of displays to accommodate venues with limited exhibition space. We welcome your questions regarding “Expedition Conquistador” For additional information or to book reservations please contact Rudolph F. Pascucci The Palm Beach Museum of Natural History [email protected] (561) 729-4246 Expedition Conquistador Expedition Conquistador provides the The beginnings of European colonization in public with a vision of what life was like for the New World began a series of violent the earliest European explorers of the New changes. Cultures and technology both World as they battled to claim territory, clashed on a monumental basis. -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

Nevada Athletic Commission

STATE OF NEVADA BOXING SHOW RESULTS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY DATE: MAY 5, 2007 LOCATION: MGM GRAND GARDEN ARENA, LAS VEGAS ATHLETIC COMMISSION Referees: Kenny Bayless, Robert Byrd, Joe Cortez, Vic Drakulich, Jay Nady, Tony Weeks Telephone (702) 486-2575 Fax (702) 486-2577 Judges: Adalaide Byrd, Burt Clements, Chuck Giampa, Bill Graham, Dick Houck, Robert Hoyle, Patricia Morse Jarman, Al Lefkowitz, Dave Moretti, C.J. Ross, Jerry Roth, Dalby Shirley, Paul Smith, COMMISSION MEMBERS: Chairman: Dr. Tony Alamo Glenn Trowbridge Visiting Judge: Tom Kaczmarek Skip Avansino, Jr. Timekeepers: Jim Cavin & Mike LaCella John R. Bailey Joe W. Brown Ringside Doctors: William Berliner, David Watson, Al Capanna, Steven Brown T. J. Day Ring Announcer: Michael Buffer & Lupe Contreras EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Keith Kizer Promoter: Golden Boy Promotions & Don Chargin Productions Matchmaker: Eric Gomez Contestants Results Federal ID Rds Date of Birth Weight Remarks Number OSCAR DE LA HOYA Mayweather won by split decision. CA036576 02/04/73 154 De La Hoya – Mayweather Los Angeles, CA 113-115; 112-116; 115-113 ----- vs ----- **Mayweather wins WBC Super 12 Roth, Giampa, Kaczmarek FLOYD JOY MAYWEATHER, JR. Welterweight title NV045572 02/24/77 150 Referee: Kenny Bayless Las Vegas, NV RICARDO JUAREZ Juarez won by unanimous decision. TX060318 04/15/80 125.5 Suspend Juarez until 06/20/07 Houston, TX Juarez – Hernandez No contact until 06/05/07 – left eye laceration ----- vs ----- 115-112; 116-111; 117-110 12 JOSE ANDRES HERNANDEZ Trowbridge, Clements, Byrd Suspend Hernandez until 06/05/07 No contact until 05/27/07 Round Lake, IL **Juarez wins vacant WBA Fedalatin IL042530 09/17/75 125.5 Featherweight title Referee: Tony Weeks REYNALDO D. -

Social Valuation of Regulating and Cultural Ecosystem Services of Arroceros Forest Park a Man-Made Forest in the City of Manila

Journal of Urban Management xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Urban Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jum Social valuation of regulating and cultural ecosystem services of Arroceros Forest Park: A man-made forest in the city of Manila, Philippines ⁎ Arthur J. Lagbasa,b, a Construction Engineering and Management Department, Integrated Research and Training Center, Technological University of the Philippines, Ayala Boulevard Corner San Marcelino Street, Ermita, Manila 1000, Philippines b Chemistry Department, College of Science, Technological University of the Philippines, Ayala Boulevard corner San Marcelino Street, Ermita, Manila 1000, Philippines ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Investment in urban green spaces such as street trees and forest park may be viewed as both Social valuation sustainable adaptation and mitigation strategies in responding to a variety of climate change Ecosystem services issues and urban environmental problems in densely urbanized areas. Urban green landscapes College students can be important sources of ecosystem services (ES) having substantial contribution to the sus- Forest park tainability of urban areas and cities of developing countries in particular. In the highly urbanized Willingness to pay highly urbanized city City of Manila in the Philippines, Arroceros Forest Park (AFP) is a significant source of regulating and cultural ES. In this study the perceived level of importance of 6 urban forest ES, attitude to the forest park non-use values, and the factors influencing willingness to pay (WTP) for forest park preservation were explored through a survey conducted on January 2018 to the college students (17–28 years, n=684) from 4 universities in the City of Manila. -

The Spanish Conquistadores and Colonial Empire

The Spanish Conquistadores and Colonial Empire Treaty of Tordesillas Columbus’s colonization of the Atlantic islands inaugurated an era of aggressive Spanish expansion across the Atlantic. Spanish colonization after Columbus accelerated the rivalry between Spain and Portugal to an unprecedented level. The two powers vied for domination through the acquisition of new lands. In the 1480s, Pope Sixtus IV had granted Portugal the right to all land south of the Cape Verde islands, leading the Portuguese king to claim that the lands discovered by Columbus belonged to Portugal, not Spain. But in 1493, Spanish-born Pope Alexander VI issued two papal decrees giving legitimacy to Spain’s Atlantic claims over the claims of Portugal. Hoping to salvage Portugal’s holdings, King João II negotiated a treaty with Spain. The Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 drew a north-to-south line through South America. Spain gained territory west of the line, while Portugal retained the lands east of the line, including the east coast of Brazil. Map of the land division determined by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons Conquistadores and Spanish colonization Columbus’s discovery opened a floodgate of Spanish exploration. Inspired by tales of rivers of gold and timid, malleable native peoples, later Spanish explorers were relentless in their quest for land and gold. Spanish explorers with hopes of conquest in the New World were known as conquistadores. Hernán Cortés arrived on Hispaniola in 1504 and participated in the conquest of the Island. Cortés then led the exploration of the Yucatán Peninsula in hopes of attaining glory. -

Nytårsrejsen Til Filippinerne – 2014

Nytårsrejsen til Filippinerne – 2014. Martins Dagbog Dorte og Michael kørte os til Kastrup, og det lykkedes os at få en opgradering til business class - et gammelt tilgodebevis fra lidt lægearbejde på et Singapore Airlines fly. Vi fik hilst på vore 16 glade gamle rejsevenner ved gaten. Karin fik lov at sidde på business class, mens jeg sad på det sidste sæde i økonomiklassen. Vi fik julemad i flyet - flæskesteg med rødkål efterfulgt af ris á la mande. Serveringen var ganske god, og underholdningen var også fin - jeg så filmen "The Hundred Foot Journey", som handlede om en indisk familie, der åbner en restaurant lige overfor en Michelin-restaurant i en mindre fransk by - meget stemningsfuld og sympatisk. Den var instrueret af Lasse Hallström. Det tog 12 timer at flyve til Singapore, og flyet var helt fuldt. Flytiden mellem Singapore og Manila var 3 timer. Vi havde kun 30 kg bagage med tilsammen (12 kg håndbagage og 18 kg i en indchecket kuffert). Jeg sad ved siden af en australsk student, der skulle hjem til Perth efter et halvt år i Bergen. Hans fly fra Lufthansa var blevet aflyst, så han havde måttet vente 16 timer i Københavns lufthavn uden kompensation. Et fly fra Air Asia på vej mod Singapore forulykkede med 162 personer pga. dårligt vejr. Miriams kuffert var ikke med til Manilla, så der måtte skrives anmeldelse - hun fik 2200 pesos til akutte fornødenheder. Vi vekslede penge som en samlet gruppe for at spare tid og gebyr - en $ var ca. 45 pesos. Vi kom i 3 minibusser ind til Manila Hotel, hvor det tog 1,5 time at checke os ind på 8 værelser. -

The Manila Galleon and the First Globalization of World Trade

October 2020 ISSN 2444-2933 The Manila Galleon and the first globalization of world trade BY Borja Cardelús The route that united Asia, America and Europe The Manila Galleon and the first The Manila Galleon and the first globalization of world trade globalization of world trade THE LONG CONQUEST OF THE PACIFIC Despite all that, the final balance of all these misfortunes and frustrations was not entirely negative because the navigations allowed to The persistence of examine the climates and contours of that The persistence of Spain of the 16th century as Spanish sailor, serving the Spanish Crown, unprecedented ocean full of islands and Spain of the 16th made it possible to conquer an ocean as found the desired path and sailed the ocean for atolls,and above all its most relevant untamable as the Pacific, a century in which it the first time, but he died in a skirmish with century made it characteristic, for the purposes of the Spanish faced two types of conquests, all equally natives in the Filipino archipelago, when he possible to conquer claims to master it; although the trip through the astonishing. One was the terrestrial, that of had already accomplished most of his feats. It was Pacific from America to Asia was easy due to the an ocean as America, achieved in the surprising period of completed by Juan Sebastian Elcano aboard the favorable push of the trade winds, the return only fifty years. ship Victoria, full of spices, and when arriving to untamable as the trip, the return voyage, was revealing the Iberian Peninsula, after the long voyage, he Pacific, a century in impossible.