The Cosmology of H. P. Lovecraft*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian SF News 28

NUMBER 28 registered by AUSTRALIA post #vbg2791 95C Volume 4 Number 2 March 1982 COW & counts PUBLISH 3 H£W ttOVttS CORY § COLLINS have published three new novels in their VOID series. RYN by Jack Wodhams, LANCES OF NENGESDUL by Keith Taylor and SAPPHIRE IN THIS ISSUE: ROAD by Wynne Whiteford. The recommended retail price on each is $4.95 Distribution is again a dilemna for them and a^ter problems with some DITMAR AND NEBULA AWARD NOMINATIONS, FRANK HERBERT of the larger paperback distributors, it seems likely that these titles TO WRITE FIFTH DUNE BOOK, ROBERT SILVERBERG TO DO will be handled by ALLBOOKS. Carey Handfield has just opened an office in Melbourne for ALLBOOKS and will of course be handling all their THIRD MAJIPOOR BOOK, "FRIDAY" - A NEW ROBERT agencies along with NORSTRILIA PRESS publications. HEINLEIN NOVEL DUE OUT IN JUNE, AN APPRECIATION OF TSCHA1CON GOH JACK VANCE BY A.BERTRAM CHANDLER, GEORGE TURNER INTERVIEWED, Philip K. Dick Dies BUG JACK BARRON TO BE FILMED, PLUS MORE NEWS, REVIEWS, LISTS AND LETTERS. February 18th; he developed pneumonia and a collapsed lung, and had a second stroke on February 24th, which put him into a A. BERTRAM CHANDLER deep coma and he was placed on a respir COMPLETES NEW NOVEL ator. There was no brain activity and doctors finally turned off the life A.BERTRAM CHANDLER has completed his support system. alternative Australian history novel, titled KELLY COUNTRY. It is in the hands He had a tremendous influence on the sf of his agents and publishers. GRIMES field, with a cult following in and out of AND THE ODD GODS is a short sold to sf fandom, but with the making of the Cory and Collins and IASFM in the U.S.A. -

GUÍA De Creación De Personaje CTHULHU

Foundation for Archeological Research Guía para nuevos miembros Una guía no-oficial para crear investigadores para el juego de rol “La Llamada de Cthulhu” ” publicado en España por Edge Entertainment bajo licencia de Chaosium. Para ser utilizado principalmente en “Los Misterios de Bloomfield”-“The Bloomfield Mysteries”, una adaptación de “La Sombra de Saros”, campaña escrita por Xabier Ugalde, para su uso en las aulas de Primaria en las áreas de Ciencias Sociales, Lengua Castellana y Lengua Extranjera: Inglés Adaptado para Educación Primaria por: ÓscarRecio Coll [email protected] https://jueducacion.com/ El Copyright de las ilustraciones de La Llamada de Cthulhu y de La Sombra de Saros además de otras presentes en este material así como la propiedad intelectual/comercial/empresarial y derechos de las mismas son exclusiva de sus autores y/o de las compañías y editoriales que sean propietarias o hayan comprado los citados derechos sobre las obras y posean sobre ellas el derecho a que se las elimine de esta publicación de tal manera que sus derechos no queden vulnerados en ninguna forma o modo que pudiera contravenir su autoría para particulares y/o empresas que las hayan utilizado con fines comerciales y/o empresariales. Esta compilación no tiene ningún uso comercial ni ánimo de lucro y está destinada exclusivamente a su utilización dentro del ámbito escolar y su finalidad es completamente didáctica como material de desarrollo y apoyo para la dinamización de contenidos en las diferentes áreas que componen la Educación Primaria. Bienvenidos/as a la F.A.R. (Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas), en este sencillo manual encontrarás las instrucciones para ser parte de nuestra fundación y completar tu registro como miembro. -

FAQ/Errata Version 4.2

FAQ/ERRATA VERSION 4.2 - Changes are denoted in red text. This document contains the card clarification and errata, rules clarifications, timing structure, and frequently asked questions for the Call of Cthulhu Living Card Game. All official play and tournaments will use the most recent version of this document to supplement the most recent Call of Cthulhu LCG rulebook. The version number will appear in front of every entry so you can easily see which changes have been made with every revision of this document. Call of Cthulhu ©2005, 2010 Fantasy Flight Games. Call of Cthulhu Living Card Game, the logo, Fantasy Flight Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to distribute this document electronically or by traditional publishing means as long as it is not altered in any way and all copyright notices are attached. Table of Contents Card Clarification and Errata p 3 Official Rules Clarification p 7 Timing Structure p 14 Frequently Asked Questions p 18 The Spawn of theSleeper The Antediluvian Dreams Dynamite (F42) Trent Dixon (F6) Should have the Attachment subtype. Should read: “…If Trent Dixon is the only character you control that is Across Dimensions (F53) committed to a story, count his skill and Should read: “Play only if every icons to all other story cards as well.” character you control has the < When he is committed alone on his faction…” controller’s turn, the application Eat the Dead Core Set of Trent Dixon’s skill and icons to the other stories does not cause (F56)Should read: “…Disrupt: those stories to resolve. -

Malleus Monstrorumsampleexpanded English File Edition Is Published by Chaosium Inc

Sample file —EXPANDED ENGLISH EDITION IN 380 ENTRIES— by Scott David Aniolowski with Sandy Petersen & Lynn Willis Additional Material by: David Conyers, Keith Herber, Kevin Ross, ChadSample J. Bowser, Shannon file Appel, Christian von Aster, Joachim A. Hagen, Florian Hardt, Frank Heller, Peter Schott, Steffen Schuütte, Michael Siefner, Jan Cristof Steines, Holger Göttmann, Wolfang Schiemichen, Ingo Ahrens, and friends. For fuller Author credits see pages 4 and 288. Project & Layout: Charlie Krank Cover Painting: Lee Gibbons Illustrated by: Pascal D. Bohr, Konstantyn Debus, Nils Eckhardt, Thomas Ertmer, Kostja Kleye, Jan Kluczewitz, Christian Küttler, Klaas Neumann, Patrick Strietzel, Jens Weber, Maria Luisa Witte, Lydia Ortiz, Paul Carrick. Art direction and visual concept: Konstantyn Debus (www.yllustration.com) Participants in the German Edition: Frank Heller, Konstantyn Debus, Peter Schott, Thomas M. Webhofer, Ingo Ahrens, Jens Kaufmann, Holger Göttmann, Christina Wessel, Maik Krüger, Holger Rinke, Andreas Finkernagel, 15brötchenmann Find more information at www.pegasus.de German to English Translation: Bill Walsh Layout Assistance: Alan Peña, Lydia Ortiz Chaosium is: Lynn Willis, Charlie Krank, Dustin Wright, Fergie, and a few odd critters. A CHAOSIUM PUBLICATION • 2006 M’bwa, megalodon, the Million Favoured Ones, the Complete Credits mind parasites, the miri nigri, M’nagalah, Mordiggian, moose, M’Tlblys, the nioth-korghai, Nug & Yeb, octo- Scott David Aniolowski: the children of Abhoth, pus, Ossadagowah, Othuum, the minions of Othuum, -

Extraterrestrial Places in the Cthulhu Mythos

Extraterrestrial places in the Cthulhu Mythos 1.1 Abbith A planet that revolves around seven stars beyond Xoth. It is inhabited by metallic brains, wise with the ultimate se- crets of the universe. According to Friedrich von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Nyarlathotep dwells or is im- prisoned on this world (though other legends differ in this regard). 1.2 Aldebaran Aldebaran is the star of the Great Old One Hastur. 1.3 Algol Double star mentioned by H.P. Lovecraft as sidereal The double star Algol. This infrared imagery comes from the place of a demonic shining entity made of light.[1] The CHARA array. same star is also described in other Mythos stories as a planetary system host (See Ymar). The following fictional celestial bodies figure promi- nently in the Cthulhu Mythos stories of H. P. Lovecraft and other writers. Many of these astronomical bodies 1.4 Arcturus have parallels in the real universe, but are often renamed in the mythos and given fictitious characteristics. In ad- Arcturus is the star from which came Zhar and his “twin” dition to the celestial places created by Lovecraft, the Lloigor. Also Nyogtha is related to this star. mythos draws from a number of other sources, includ- ing the works of August Derleth, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Brian Lumley, and Clark Ashton Smith. 2 B Overview: 2.1 Bel-Yarnak • Name. The name of the celestial body appears first. See Yarnak. • Description. A brief description follows. • References. Lastly, the stories in which the celes- 3 C tial body makes a significant appearance or other- wise receives important mention appear below the description. -

Ye Bc 3Ke of 2358

YE BC 3KE OF 2358 < The Aniolowsk’i Collection. VOLUME II All About Monstres This volume contains dozens of new races and individual creatures for use with the Call of Cthulhu roleplaying game. Included here are the following categories: Outer Gods, Elder Gods, Great Old Ones, Great Ones, Avatars, Servitor Races, Independent Races, Fabulous Creatures, and Unique Entities. These monstrous creations have been collected from over ten years of favorite Call of Cthulhu scenarios; others have been created specifically for this book. The darkly imagi- native work of a diverse group of authors is represented here. Where possible each entry begins with a quote describing the monster or entity. Where much about the creature is known, there may be an additional description. If discussing a god, Great One, or Great Old One, notice of any human cult comes next. Further notes discuss habit, habitat, or attack. An essential aid for players, investigators, and keepers. “I saw the form waver from sex to sex, dividing itself from itself, and then again reunited. Then I saw the body descend to the beastsSample whence file it ascended, and that which was on the heights go down to the depths, even to the abyss of all being... I The principle of life, which makes organism, always Scott David Aniolowski remained, while the outward form changed. ” (after his apprehensio: by -Arthur Machen, “The Great God Pan” minions of the Mythos) CALL OF CTHULHU is a roleplaying game Chaosium publishes many supplements based on the novels and short stories of H.P. and accessories for CALL OF CTHULHU. -

Pandemic: Reign of Cthulhu Rulebook

Beings of ancient and bizarre intelligence, known as Old Ones, are stirring within their vast cosmic prisons. If they awake into the world, it will unleash an age of madness, chaos, and destruction upon the very fabric of reality. Everything you know and love will be destroyed! You are cursed with knowledge that the “sleeping masses” cannot bear: that this Evil exists, and that it must be stopped at all costs. Shadows danced all around the gas street light above you as the pilot flame sputtered a weak yellow light. Even a small pool of light is better than total darkness, you think to yourself. You check your watch again for the third time in the last few minutes. Where was she? Had something happened? The sound of heels clicking on pavement draws your eyes across the street. Slowly, as if the darkness were a cloak around her, a woman comes into view. Her brown hair rests in a neat bun on her head and glasses frame a nervous face. Her hands hold a large manila folder with the words INNSMOUTH stamped on the outside in blocky type lettering. “You’re late,” you say with a note of worry in your voice, taking the folder she is handing you. “I… I tried to get here as soon as I could.” Her voice is tight with fear, high pitched and fast, her eyes moving nervously without pause. “You know how to fix this?” The question in her voice cuts you like a knife. “You can… make IT go away?!” You wince inwardly as her voice raises too loudly at that last bit, a nervous edge of hysteria creeping into her tone. -

Machen, Lovecraft, and Evolutionary Theory

i DEADLY LIGHT: MACHEN, LOVECRAFT, AND EVOLUTIONARY THEORY Jessica George A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University March 2014 ii Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between evolutionary theory and the weird tale in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through readings of works by two of the writers most closely associated with the form, Arthur Machen (1863-1947) and H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), it argues that the weird tale engages consciously, even obsessively, with evolutionary theory and with its implications for the nature and status of the “human”. The introduction first explores the designation “weird tale”, arguing that it is perhaps less useful as a genre classification than as a moment in the reception of an idea, one in which the possible necessity of recalibrating our concept of the real is raised. In the aftermath of evolutionary theory, such a moment gave rise to anxieties around the nature and future of the “human” that took their life from its distant past. It goes on to discuss some of the studies which have considered these anxieties in relation to the Victorian novel and the late-nineteenth-century Gothic, and to argue that a similar full-length study of the weird work of Machen and Lovecraft is overdue. The first chapter considers the figure of the pre-human survival in Machen’s tales of lost races and pre-Christian religions, arguing that the figure of the fairy as pre-Celtic survival served as a focal point both for the anxieties surrounding humanity’s animal origins and for an unacknowledged attraction to the primitive Other. -

Terror Handouts

TERROR HANDOUTS This supplement is best used with the Call of Cthulhu (7th Edition) roleplaying game, and optionally the Pulp Cthulhu sourcebook, both available separately. Terror Australis © copyright 2018–2020 Chaosium Inc. All rights reserved. Call of Cthulhu © copyright 1981–2020 Chaosium Inc. Pulp Cthulhu © copyright 2016–2020 Chaosium Inc. All rights reserved. Chaosium Arcane Symbol (the Star Elder Sign) © copyright 1983 Chaosium Inc. All rights reserved. Call of Cthulhu, Chaosium Inc., and the Chaosium logo are registered trademarks of Chaosium Inc. Pulp Cthulhu is a trademark of Chaosium Inc. All rights reserved. Ithaqua © copyright 2020 the Estate of August Derleth. Used with permission. Atlach-Nacha and Tsathoggua © copyright 2020 the Estate of Clark Ashton Smith. Used with permission. Chaosium recognizes that credits and copyrights for the Cthulhu Mythos can be difficult to identify, and that some elements of the Mythos may be in the public domain. If you have corrections or additions to any credits given here, please contact us at [email protected]. This is a work of fiction. This book includes descriptions and portrayals of real places, real events, and real people; these may not be presented accurately and with conformity to the real-world nature of these places, people, and events, and are reinterpreted through the lens of the Cthulhu Mythos and the Call of Cthulhu game in general. No offense to anyone living or dead, or to the inhabitants of any of these places, is intended. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Reproduction of this work by any means without written permission of Chaosium Inc., except for the use of short excerpts for the purpose of reviews and the copying of character sheets and handouts for in-game use, is expressly prohibited. -

The Unspeakable Oath Issues 1 & 2 Page 1

The Unspeakable Oath issues 1 & 2 Page 1 Introduction to The Annotated Unspeakable Oath ©1993 John Tynes This is a series of freely-distributable text files that presents the textual contents of early issues of THE UNSPEAKABLE OATH, the world’s premiere digest for Chaosium’s CALL OF CTHULHU ™ role-playing game. Each file contains the nearly-complete text from a given issue. Anything missing is described briefly with the file, and is missing either due to copyright problems or because the information has been or will be reprinted in a commercial product. Everything in this file is copyrighted by the original authors, and each section carries that copyright. This file may be freely distributed provided that no money is charged whatsoever for its distribution. This file may only be distributed if it is intact, whole, and unchanged. All copyright notices must be retained. Modified versions may not be distributed — the contents belong to the creators, so please respect their work. Abusing my position as editor and instigator of the magazine and this project, I have taken the liberty of adding comments to some of the contents where I thought I had something interesting or historically worth preserving to say. Yeah, right! – John Tynes, editor-in-chief of Pagan Publishing The Unspeakable Oath issues 1 & 2 Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction to The Annotated Unspeakable Oath...................................................................................2 Introduction to TUO 1.........................................................................................................................4 -

Dunwich Horror by Sean Branney with Andrew Leman

Dark Adventure Radio Theatre: The Dunwich Horror by Sean Branney With Andrew Leman Based on "The Dunwich Horror" by H.P. Lovecraft Read-along Script ©2008, HPLHS, Inc., all rights reserved Static, radio tuning, snippet of 30s song, more tuning, static dissolves to: Dark Adventure Radio theme music. ANNOUNCER Tales of intrigue, adventure, and the mysterious occult that will stir your imagination and make your very blood run cold. Music crescendo. ANNOUNCER This is Dark Adventure Radio Theatre, with your host Chester Langfield. Today’s episode: H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror”. Music diminishes. CHESTER LANGFIELD The hills of Western Massachusetts contain dark and terrible secrets. Strange families keep to themselves and practice rites of ancient and unspeakable black magic. These dreadful and unholy rituals give birth to a monstrosity beyond imagination, a monstrosity that threatens mankind itself! Can a brave handful of intrepid scholars hope to confront the otherwordly destruction of “The Dunwich Horror”? But first a word from our sponsor. A few piano notes from the Fleur de Lys jingle. CHESTER LANGFIELD When I sit down to enjoy a meal, the first thing I do is light up a Fleur de Lys cigarette. Not only do they enhance the taste of food, Fleur de Lys aid in the digestive process. Our cigarettes are made from finer costlier tobaccos than other brands, providing you with the very best in freshness and flavor. So, for the sake of digestion, during and after meals be sure to smoke Fleur de Lys! Dark Adventure lead-in music. DART: The Dunwich Horror 2. -

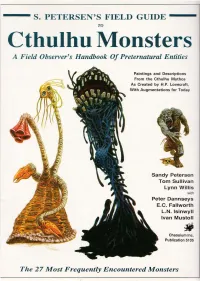

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book.