Fall of Carthage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Citations in Classics and Ancient History

Citations in Classics and Ancient History The most common style in use in the field of Classical Studies is the author-date style, also known as Chicago 2, but MLA is also quite common and perfectly acceptable. Quick guides for each of MLA and Chicago 2 are readily available as PDF downloads. The Chicago Manual of Style Online offers a guide on their web-page: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html The Modern Language Association (MLA) does not, but many educational institutions post an MLA guide for free access. While a specific citation style should be followed carefully, none take into account the specific practices of Classical Studies. They are all (Chicago, MLA and others) perfectly suitable for citing most resources, but should not be followed for citing ancient Greek and Latin primary source material, including primary sources in translation. Citing Primary Sources: Every ancient text has its own unique system for locating content by numbers. For example, Homer's Iliad is divided into 24 Books (what we might now call chapters) and the lines of each Book are numbered from line 1. Herodotus' Histories is divided into nine Books and each of these Books is divided into Chapters and each chapter into line numbers. The purpose of such a system is that the Iliad, or any primary source, can be cited in any language and from any publication and always refer to the same passage. That is why we do not cite Herodotus page 66. Page 66 in what publication, in what edition? Very early in your textbook, Apodexis Historia, a passage from Herodotus is reproduced. -

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 1

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Lecture 18 Roman Agricultural History Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius View from the Tower of Mercury on the Pompeii city wall looking down the Via di Mercurio toward the forum 1 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Rome 406–88 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 241–27 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 193–211 Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. 2 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Carthage Founded 814 BCE in North Africa Result of Phoenician expansion North African city-state opposite Sicily Mago, 350 BCE, Father of Agriculture Agricultural author wrote a 28 volume work in Punic, A language close to Hebrew. Roman Senate ordered the translation of Mago upon the fall of Carthage despite violent enmity between states. One who has bought land should sell his town house so that he will have no desire to worship the households of the city rather than those of the country; the man who takes great delight in his city residence will have no need of a country estate. Quotation from Columella after Mago Hannibal Capitoline Museums Hall of Hannibal Jacopo Ripanda (attr.) Hannibal in Italy Fresco Beginning of 16th century Roman History 700 BCE Origin from Greek Expansion 640–520 Etruscan civilization 509 Roman Republic 264–261 Punic wars between Carthage and Rome 3 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Roman Culture Debt to Greek, Egyptian, and Babylonian Science and Esthetics Roman expansion due to technology and organization Agricultural Technology Irrigation Grafting Viticulture and Enology Wide knowledge of fruit culture, pulses, wheat Legume rotation Fertility appraisals Cold storage of fruit Specularia—prototype greenhouse using mica Olive oil for cooking and light Ornamental Horticulture Hortus (gardens) Villa urbana Villa rustica, little place in the country Formal gardens of wealthy Garden elements Frescoed walls, statuary, fountains trellises, pergolas, flower boxes, shaded walks, terraces, topiary Getty Museum reconstruction of the Villa of the Papyri. -

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar Ve Yorumlar

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar ve Yorumlar David Pierce October , Matematics Department Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul http://mat.msgsu.edu.tr/~dpierce/ Preface Here are notes of what I have been able to find or figure out about Thales of Miletus. They may be useful for anybody interested in Thales. They are not an essay, though they may lead to one. I focus mainly on the ancient sources that we have, and on the mathematics of Thales. I began this work in preparation to give one of several - minute talks at the Thales Meeting (Thales Buluşması) at the ruins of Miletus, now Milet, September , . The talks were in Turkish; the audience were from the general popu- lation. I chose for my title “Thales as the originator of the concept of proof” (Kanıt kavramının öncüsü olarak Thales). An English draft is in an appendix. The Thales Meeting was arranged by the Tourism Research Society (Turizm Araştırmaları Derneği, TURAD) and the office of the mayor of Didim. Part of Aydın province, the district of Didim encompasses the ancient cities of Priene and Miletus, along with the temple of Didyma. The temple was linked to Miletus, and Herodotus refers to it under the name of the family of priests, the Branchidae. I first visited Priene, Didyma, and Miletus in , when teaching at the Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince, Selçuk, İzmir. The district of Selçuk contains also the ruins of Eph- esus, home town of Heraclitus. In , I drafted my Miletus talk in the Math Village. Since then, I have edited and added to these notes. -

Polybius: the Histories Translated by W

Polybius: The Histories Translated by W. R. Paton From BOOK ONE own existence. The Lacedaemonians, after AD previous chroniclers neglected to having for many years disputed the hegemony speak in praise of History in general, of Greece, at length attained it but to hold it H it might perhaps have been necessary uncontested for scarce twelve years. The for me to recommend everyone to choose for Macedonian rule in Europe extended but from study and welcome such treatises as the the Adriatic to the Danube, which would present, since there is no more ready appear a quite insignificant portion of the corrective of conduct than knowledge of the continent. Subsequently, by overthrowing the past. But all historians, one may say without Persian empire they became supreme in Asia exception, and in no half-hearted manner, but also. But though their empire was now making this the beginning and end of their regarded as the greatest in extent and power labor, have impressed on us that the soundest that had ever existed, they left the larger part education and training for a life of active of the inhabited world as yet outside it. For politics is the study of History, and that the they never even made a single attempt on surest and indeed the only method of learning Sicily, Sardinia, or Africa, and the most how to bear bravely the vicissitudes of warlike nations of Western Europe were, to fortune, is to recall the calamities of others. speak the simple truth, unknown to them. But Evidently therefore one, and least of all the Romans have subjected to their rule not myself, would think it his duty at this day to portions, but nearly the whole of the world, repeat what has been so well and so often said. -

Passionate Platonism: Plutarch on the Positive Role of Non-Rational Affects in the Good Life

Passionate Platonism: Plutarch on the Positive Role of Non-Rational Affects in the Good Life by David Ryan Morphew A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Victor Caston, Chair Professor Sara Ahbel-Rappe Professor Richard Janko Professor Arlene Saxonhouse David Ryan Morphew [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-4773-4952 ©David Ryan Morphew 2018 DEDICATION To my wife, Renae, whom I met as I began this project, and who has supported me throughout its development. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I am grateful to my advisors and dissertation committee for their encouragement, support, challenges, and constructive feedback. I am chiefly indebted to Victor Caston for his comments on successive versions of chapters, for his great insight and foresight in guiding me in the following project, and for steering me to work on Plutarch’s Moralia in the first place. No less am I thankful for what he has taught me about being a scholar, mentor, and teacher, by his advice and especially by his example. There is not space here to express in any adequate way my gratitude also to Sara Ahbel-Rappe and Richard Janko. They have been constant sources of inspiration. I continue to be in awe of their ability to provide constructive criticism and to give incisive critiques coupled with encouragement and suggestions. I am also indebted to Arlene Saxonhouse for helping me to see the scope and import of the following thesis not only as of interest to the history of philosophy but also in teaching our students to reflect on the kind of life that we want to live. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

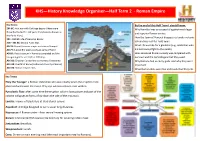

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

Women in Pompeii Author(S): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol

Women in Pompeii Author(s): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 5 (September/October 1979), pp. 34-43 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41726375 . Accessed: 19/03/2014 08:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 170.24.130.117 on Wed, 19 Mar 2014 08:08:22 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Wfomen in Pompeii by Elizabeth Lyding Will year 1979 marks the 1900th anniversary of the fatefulburial of Pompeii, Her- The culaneum and the other sitesengulfed by the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79. It was the most devastatingdisaster in the Mediterranean area since the volcano on Thera erupted one and a half millenniaearlier. The suddenness of the A well-bornPompeian woman drawn from the original wall in theHouse Ariadne PierreGusman volcanic almost froze the bus- painting of by onslaught instantly ( 1862-1941), a Frenchartist and arthistorian. Many tling Roman cityof Pompeii, creating a veritable Pompeianwomen were successful in business, including time capsule. -

A Presocratics Reader

2. THE MILESIANS Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes were all from the city of Miletus in Ionia (now the western coast of Turkey) and make up what is referred to as the Milesian “school” of philosophy. Tradition reports that Thales was the teacher of Anaximander, who in turn taught Anaximenes. Aristotle begins his account of the history of philosophy as the search for causes and principles (in Metaphysics I) with these three. 2.1. Thales Thales appears on lists of the seven sages of Greece, a traditional catalog of wise men. The chronicler Apollodorus suggests that he was born around 625 BCE. We should accept this date only with caution, as Apollodorus usually calculated birthdates by assuming that a man was forty years old at the time of his “acme,” or greatest achievement. Thus, Apollodorus arrives at the date by assuming that Thales indeed predicted an eclipse in 585 BCE, and was forty at the time. Plato and Aristotle tell stories about Thales that show that even in ancient times philosophers had a mixed reputation for practicality. 1. (11A9) They say that once when Thales was gazing upwards while doing astronomy, he fell into a well, and that a witty and charming Thracian serving-girl made fun of him for being eager to know the things in the heavens but failing to notice what was just behind him and right by his feet. (Plato, Theaetetus 174a) 2. (11A10) The story goes that when they were reproaching him for his poverty, supposing that philosophy is useless, he learned from his astronomy that the olive crop would be large. -

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) the Punic Wars

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) The Punic Wars After subjugating the Greek colonies in southern Italy, Rome sought to control western Mediterranean trade. Its chief rival, located across the Mediterranean in northern Africa, was the city-state of Carthage. Originally a Phoenician colony, Carthage had become a powerful commercial empire. Rome defeated Carthage in three Punic (Phoenician) Wars and gained mastery of the western Mediterranean. The First Punic War (264-241 B.C.) Fighting chiefly on the island of Sicily and in the Mediterranean Sea, Rome’s citizen-soldiers eventually defeated Carthage’s mercenaries(hired foreign soldiers). Rome annexed Sicily and then Sardinia and Corsica. Both sides prepared to renew the struggle. Carthage acquired a part of Spain and recruited Spanish troops. Rome consolidated its position in Italy by conquering the Gauls, thereby extending its rule northward from the Po River to the Alps. The Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) Hannibal, Carthage’s great general, led an army from Spain across the Alps and into Italy. At first he won numerous victories, climaxed by the battle of Cannae. However, he was unable to seize the city of Rome. Gradually the tide of battle turned in favor of Rome. The Romans destroyed a Carthaginian army sent to reinforce Hannibal, then conquered Spain, and finally invaded North Africa. Hannibal withdrew his army from Italy to defend Carthage but, in the Battle of Zama, was at last defeated. Rome annexed Carthage’s Spanish provinces and reduced Carthage to a second-rate power. Hannibal of Carthage Reasons for Rome’s Victory • superior wealth and military power, • the loyalty of most of its allies, and • the rise of capable generals, notably Fabius and Scipio. -

Contesting the Greatness of Alexander the Great: the Representation of Alexander in the Histories of Polybius and Livy

ABSTRACT Title of Document: CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY Nikolaus Leo Overtoom, Master of Arts, 2011 Directed By: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Department of History By investigating the works of Polybius and Livy, we can discuss an important aspect of the impact of Alexander upon the reputation and image of Rome. Because of the subject of their histories and the political atmosphere in which they were writing - these authors, despite their generally positive opinions of Alexander, ultimately created scenarios where they portrayed the Romans as superior to the Macedonian king. This study has five primary goals: to produce a commentary on the various Alexander passages found in Polybius’ and Livy’s histories; to establish the generally positive opinion of Alexander held by these two writers; to illustrate that a noticeable theme of their works is the ongoing comparison between Alexander and Rome; to demonstrate Polybius’ and Livy’s belief in Roman superiority, even over Alexander; and finally to create an understanding of how this motif influences their greater narratives and alters our appreciation of their works. CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY By Nikolaus Leo Overtoom Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Chair Professor Judith P. Hallett Professor Kenneth G. Holum © Copyright by Nikolaus Leo Overtoom 2011 Dedication in amorem matris Janet L. -

The Fragments of Zeno and Cleanthes, but Having an Important

,1(70 THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES. ftonton: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, AVE MARIA LANE. ambriDse: DEIGHTON, BELL, AND CO. ltip>ifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS. #tto Hork: MACMILLAX AND CO. THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES WITH INTRODUCTION AND EXPLANATORY NOTES. AX ESSAY WHICH OBTAINED THE HARE PRIZE IX THE YEAR 1889. BY A. C. PEARSON, M.A. LATE SCHOLAR OF CHRIST S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. LONDON: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE. 1891 [All Rights reserved.] Cambridge : PBIXTKIi BY C. J. CLAY, M.A. AND SONS, AT THK UNIVERSITY PRKSS. PREFACE. S dissertation is published in accordance with thr conditions attached to the Hare Prize, and appears nearly in its original form. For many reasons, however, I should have desired to subject the work to a more under the searching revision than has been practicable circumstances. Indeed, error is especially difficult t<> avoid in dealing with a large body of scattered authorities, a the majority of which can only be consulted in public- library. to be for The obligations, which require acknowledged of Zeno and the present collection of the fragments former are Cleanthes, are both special and general. The Philo- soon disposed of. In the Neue Jahrbticher fur Wellmann an lofjie for 1878, p. 435 foil., published article on Zeno of Citium, which was the first serious of Zeno from that attempt to discriminate the teaching of Wellmann were of the Stoa in general. The omissions of the supplied and the first complete collection fragments of Cleanthes was made by Wachsmuth in two Gottingen I programs published in 187-i LS75 (Commentationes s et II de Zenone Citiensi et Cleaitt/ie Assio).