The Road to Nicea a Survey of the Regional Differences Influencing the Development of the Doctrine of the Trinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 1

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Lecture 18 Roman Agricultural History Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius View from the Tower of Mercury on the Pompeii city wall looking down the Via di Mercurio toward the forum 1 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Rome 406–88 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 241–27 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 193–211 Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. 2 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Carthage Founded 814 BCE in North Africa Result of Phoenician expansion North African city-state opposite Sicily Mago, 350 BCE, Father of Agriculture Agricultural author wrote a 28 volume work in Punic, A language close to Hebrew. Roman Senate ordered the translation of Mago upon the fall of Carthage despite violent enmity between states. One who has bought land should sell his town house so that he will have no desire to worship the households of the city rather than those of the country; the man who takes great delight in his city residence will have no need of a country estate. Quotation from Columella after Mago Hannibal Capitoline Museums Hall of Hannibal Jacopo Ripanda (attr.) Hannibal in Italy Fresco Beginning of 16th century Roman History 700 BCE Origin from Greek Expansion 640–520 Etruscan civilization 509 Roman Republic 264–261 Punic wars between Carthage and Rome 3 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Roman Culture Debt to Greek, Egyptian, and Babylonian Science and Esthetics Roman expansion due to technology and organization Agricultural Technology Irrigation Grafting Viticulture and Enology Wide knowledge of fruit culture, pulses, wheat Legume rotation Fertility appraisals Cold storage of fruit Specularia—prototype greenhouse using mica Olive oil for cooking and light Ornamental Horticulture Hortus (gardens) Villa urbana Villa rustica, little place in the country Formal gardens of wealthy Garden elements Frescoed walls, statuary, fountains trellises, pergolas, flower boxes, shaded walks, terraces, topiary Getty Museum reconstruction of the Villa of the Papyri. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

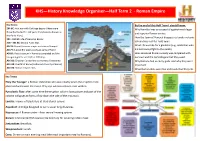

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

Women in Pompeii Author(S): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol

Women in Pompeii Author(s): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 5 (September/October 1979), pp. 34-43 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41726375 . Accessed: 19/03/2014 08:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 170.24.130.117 on Wed, 19 Mar 2014 08:08:22 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Wfomen in Pompeii by Elizabeth Lyding Will year 1979 marks the 1900th anniversary of the fatefulburial of Pompeii, Her- The culaneum and the other sitesengulfed by the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79. It was the most devastatingdisaster in the Mediterranean area since the volcano on Thera erupted one and a half millenniaearlier. The suddenness of the A well-bornPompeian woman drawn from the original wall in theHouse Ariadne PierreGusman volcanic almost froze the bus- painting of by onslaught instantly ( 1862-1941), a Frenchartist and arthistorian. Many tling Roman cityof Pompeii, creating a veritable Pompeianwomen were successful in business, including time capsule. -

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) the Punic Wars

Rome Conquers the Western Mediterranean (264-146 B.C.) The Punic Wars After subjugating the Greek colonies in southern Italy, Rome sought to control western Mediterranean trade. Its chief rival, located across the Mediterranean in northern Africa, was the city-state of Carthage. Originally a Phoenician colony, Carthage had become a powerful commercial empire. Rome defeated Carthage in three Punic (Phoenician) Wars and gained mastery of the western Mediterranean. The First Punic War (264-241 B.C.) Fighting chiefly on the island of Sicily and in the Mediterranean Sea, Rome’s citizen-soldiers eventually defeated Carthage’s mercenaries(hired foreign soldiers). Rome annexed Sicily and then Sardinia and Corsica. Both sides prepared to renew the struggle. Carthage acquired a part of Spain and recruited Spanish troops. Rome consolidated its position in Italy by conquering the Gauls, thereby extending its rule northward from the Po River to the Alps. The Second Punic War (218-201 B.C.) Hannibal, Carthage’s great general, led an army from Spain across the Alps and into Italy. At first he won numerous victories, climaxed by the battle of Cannae. However, he was unable to seize the city of Rome. Gradually the tide of battle turned in favor of Rome. The Romans destroyed a Carthaginian army sent to reinforce Hannibal, then conquered Spain, and finally invaded North Africa. Hannibal withdrew his army from Italy to defend Carthage but, in the Battle of Zama, was at last defeated. Rome annexed Carthage’s Spanish provinces and reduced Carthage to a second-rate power. Hannibal of Carthage Reasons for Rome’s Victory • superior wealth and military power, • the loyalty of most of its allies, and • the rise of capable generals, notably Fabius and Scipio. -

Carthage Was Indeed Destroyed

1 Carthage was indeed destroyed Introduction to Carthage According to classical texts (Polybe 27) Carthage’s history started with the Phoenician queen Elissa who was ousted from power in Tyre and in 814 BC settled with her supporters in what is now known as Carthage. There might have been conflicts with the local population and the local Berber kings, but the power of the Phoenician settlement Carthage kept growing. The Phoenicians based in the coastal cities of Lebanon constituted in the Mediterranean Sea a large maritime trade power but Carthage gradually became the hub for all East Mediterranean trade by the end of the 6th century BC. Thus Carthage evolved from being a Phoenician settlement to becoming the capital of an empire (Fantar, M.H., 1998, chapter 3). The local and the Phoenician religions mixed (e.g. Tanit and Baal) and in brief Carthage developed from its establishment in roughly 800 BC and already from 6th century BC had become the centre for a large empire of colonies across Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Spain, and the islands of Mallorca, Sardinia, and Sicily (Heimburger, 2008 p.36). Illustration: The empire of Carthage prior to the 1st Punic war in 264 BC, encyclo.voila.fr/wiki/Ports_puniques_de_Carthage 2010 Following two lost wars with the rising Rome (264-241 BC and 218-201 BC) Carthage was deprived of its right to engage in wars but experienced a very prosperous period as a commercial power until Rome besieged the city in 149 BC and in 146 BC destroyed it completely 25 years later Rome decided to rebuild the city but not until 43 BC was Carthage reconstructed as the centre for Rome’s African Province. -

The Roman Republic

1 The Roman Republic MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES POWER AND AUTHORITY The Some of the most fundamental • republic • senate early Romans established a values and institutions of • patrician •dictator republic, which grew powerful Western civilization began in the •plebeian •legion and spread its influence. Roman Republic. • tribune • Punic Wars •consul • Hannibal SETTING THE STAGE While the great civilization of Greece was in decline, a new city to the west was developing and increasing its power. Rome grew from a small settlement to a mighty civilization that eventually conquered the Mediterranean world. In time, the Romans would build one of the most famous and influential empires in history. The Origins of Rome TAKING NOTES Outlining Use an outline According to legend, the city of Rome was founded in 753 B.C.by Romulus and to organize the main Remus, twin sons of the god Mars and a Latin princess. The twins were aban- ideas and details. doned on the Tiber River as infants and raised by a she-wolf. The twins decided to build a city near the spot. In reality, it was men not immortals who built the I. The Origins of Rome A. city, and they chose the spot largely for its strategic location and fertile soil. B. Rome’s Geography Rome was built on seven rolling hills at a curve on the II. The Early Republic Tiber River, near the center of the Italian peninsula. It was midway between the A. B. Alps and Italy’s southern tip. Rome also was near the midpoint of the III. -

The Mini-Columbarium in Carthage's Yasmina

THE MINI-COLUMBARIUM IN CARTHAGE’S YASMINA CEMETERY by CAITLIN CHIEN CLERKIN (Under the Direction of N. J. Norman) ABSTRACT The Mini-Columbarium in Carthage’s Roman-era Yasmina cemetery combines regional construction methods with a Roman architectural form to express the privileged status of its wealthy interred; this combination deploys monumental architectural language on a small scale. This late second or early third century C.E. tomb uses the very North African method of vaulting tubes, in development in this period, for an aggrandizing vaulted ceiling in a collective tomb type derived from the environs of Rome, the columbarium. The use of the columbarium type signals its patrons’ engagement with Roman mortuary trends—and so, with culture of the center of imperial power— to a viewer and imparts a sense of group membership to both interred and visitor. The type also, characteristically, provides an interior space for funerary ritual and commemoration, which both sets the Mini-Columbarium apart at Yasmina and facilitates normative Roman North African funerary ritual practice, albeit in a communal context. INDEX WORDS: Funerary monument(s), Funerary architecture, Mortuary architecture, Construction, Vaulting, Vaulting tubes, Funerary ritual, Funerary commemoration, Carthage, Roman, Roman North Africa, North Africa, Columbarium, Collective burial, Social identity. THE MINI-COLUMBARIUM IN CARTHAGE’S YASMINA CEMETERY by CAITLIN CHIEN CLERKIN A.B., Bowdoin College, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2013 © 2013 Caitlin Chien Clerkin All Rights Reserved. THE MINI-COLUMBARIUM IN CARTHAGE’S YASMINA CEMETERY by CAITLIN CHIEN CLERKIN Major Professor: Naomi J. -

A Carthage Christmas a Festival of Readings and Carols Featuring the Majestic Sounds of the Fritsch Memorial Organ

A Carthage Christmas A Festival of Readings and Carols Featuring the majestic sounds of the Fritsch Memorial Organ December 6 - 8, 2013 Welcome to A Carthage Christmas For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder; and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The Mighty God The Everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace —ISAIAH 9:6 The Isabelle and William Wittig Nativity Star adorns the center of the Chapel. Gathering Deck Thyself, My Soul, With Gladness J. S. Bach Music: Carthage Concert Band (1685 – 1750) arr. Alfred Reed In dulce jubilo Dietrich Buxtehude Fritsch Memorial Organ (c. 1637–1707) This Festival program is designed to flow from beginning to end without interruption. To maintain the continuity of the program, all are encouraged to hold applause until the end of the Service of Light. Please turn off all cameras, cell phones, and other electronic devices prior to the performance. Unto Us a Child is Born Reading: Isaiah 9 The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light: they that dwelt in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined. Thou hast multiplied the nation, thou hast increased the joy: they joy before thee according to the joy in the harvest, as men rejoice when they divide the spoil. For thou hast broken the yoke of his burden, and the staff of his shoulder, the rod of his oppressor, as in the day of Midian. For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, the Mighty God, the Everlasting Father, the Prince of Peace. -

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500 Previewing Main Ideas POWER AND AUTHORITY Rome began as a republic, a government in which elected officials represent the people. Eventually, absolute rulers called emperors seized power and expanded the empire. Geography About how many miles did the Roman Empire stretch from east to west? EMPIRE BUILDING At its height, the Roman Empire touched three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa. For several centuries, Rome brought peace and prosperity to its empire before its eventual collapse. Geography Why was the Mediterranean Sea important to the Roman Empire? RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS Out of Judea rose a monotheistic, or single-god, religion known as Christianity. Based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, it soon spread throughout Rome and beyond. Geography What geographic features might have helped or hindered the spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire? INTERNET RESOURCES • Interactive Maps Go to classzone.com for: • Interactive Visuals • Research Links • Maps • Interactive Primary Sources • Internet Activities • Test Practice • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz 152 153 What makes a successful leader? You are a member of the senate in ancient Rome. Soon you must decide whether to support or oppose a powerful leader who wants to become ruler. Many consider him a military genius for having gained vast territory and wealth for Rome. Others point out that he disobeyed orders and is both ruthless and devious. You wonder whether his ambition would lead to greater prosperity and order in the empire or to injustice and unrest. ▲ This 19th-century painting by Italian artist Cesare Maccari shows Cicero, one of ancient Rome’s greatest public speakers, addressing fellow members of the Roman Senate. -

Chapter 14: the Roman Republic, 509 B.C

0218-0231 CH14-846240 10/29/02 11:39 AM Page 218 CHAPTER The Roman Republic 14 509 B.C.–30 B.C. ᭡ The Roman eagle on an onyx cameo A Roman legionary ᭤ 509 B.C. 450 B.C. 264 B.C. 46 B.C. 31 B.C. Romans set up Twelve Tables Punic Wars Julius Caesar Octavian becomes republic are written begin appointed sole ruler of dictator of Rome Roman Empire 218 UNIT 5 THE ROMANS 0218-0231 CH14-846240 10/29/02 11:39 AM Page 219 Chapter Focus Read to Discover Chapter Overview Visit the Human Heritage Web site • How the government of the Roman Republic was organized. at humanheritage.glencoe.com • How the Roman Republic was able to expand its territory. and click on Chapter 14— • How the effects of conquest changed the Roman economy Chapter Overviews to preview this chapter. and government. • How reformers attempted to save the Roman Republic. Terms to Learn People to Know Places to Locate republic Tarquin the Proud Carthage patricians Hannibal Barca Sicily plebeians Tiberius Gaul consuls Gracchus Corinth legionaries Julius Caesar dictator Mark Antony triumvirate Octavian Why It’s Important In 509 B.C., the Romans overthrew Tarquin (tar’ kwin) the Proud, their Etruscan king, and set up a repub- lic. Under this form of government, people choose their rulers. Reading Check However, not everyone had an equal say in the Roman Repub- What is a lic. The patricians (puh trish’ uhnz)—members of the oldest republic? and richest families—were the only ones who could hold pub- Who were the lic office or perform certain religious rituals. -

Carthage Was the Center Or Capital City of the Ancient Carthaginian

Carthage was the center or capital city of the ancient Carthaginian civilization, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now the Tunis Governorate in Tunisia. Carthage was widely considered the most important trading hub of the Ancient Mediterranean and was arguably one of the most affluent cities of the Ancient World. The city developed from a Phoenician colony into the capital of a Punic empire which dominated large parts of the Southwest Mediterranean during the first millennium BC. The legendary Queen Dido is regarded as the founder of the city, though her historicity has been questioned. The ancient Carthage city was destroyed by the Roman Republic in the Third Punic War in 146 BC and then re-developed as Roman Carthage, which became the major city of the Roman Empire in the province of Africa. The city was sacked and destroyed by Umayyad forces after the Battle of Carthage in 698 to prevent it from being reconquered by the Byzantine Empire. It remained occupied during the Muslim period and was used as a fort by the Muslims until the Hafsid period when it was taken by the Crusaders with its inhabitants massacred during the Eighth Crusade. Catheral of St. Vincent de Paul: is a Roman Catholic church located in Tunis, Tunisia. The cathedral is dedicated to Saint Vincent de Paul, patron saint of charity. It is the episcopal see of the Archdiocese of Tunis and is situated at Place de l'Indépendence in Ville Nouvelle, a crossroads between Avenue Habib Bourguiba and Avenue de France, opposite the French embassy. -

2017–2018 Catalog Carthage College 2017–2018 Catalog

2017–2018 Catalog Carthage College 2017–2018 Catalog This catalog is an educational guidebook for students at Carthage and describes the requirements for all academic programs and for graduation. It also provides information about financial aid and scholarships. The catalog sets forth regulations and faculty policies that govern academic life and acquaints students with Carthage faculty and staff. It is important that every student becomes familiar with the contents of the catalog. If any portion of it needs further explanation, faculty advisors and staff members are available to answer your questions. Carthage reserves the right herewith to make changes in its curriculum, regulations, tuition charges, and fees. It is the policy of Carthage and the responsibility of its administration and faculty to provide equal opportunity without regard to race, color, religion, age, sex, national origin, or sexual orientation. As part of this policy, the College strongly disapproves of any or all forms of sexual harassment in the workplace, classroom, or dormitories. This policy applies to all phases of the operation of the College. Further, the College will not discriminate against any employee, applicant for employment, Carthage College student, or applicant for admission because of physical or mental disability in regard to any 2001 Alford Park Drive position or activity for which the individual is qualified. The College will undertake appropriate Kenosha, WI 53140 activities to treat qualified disabled individuals without discrimination. (262) 551-8500 The College has been accredited continuously since 1916 by the Higher Learning Commission, Carthage Bulletin Vol. 96 North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, 30 North LaSalle St., Suite 2400, Chicago, IL 2017-2018 60602-2504, 800-621-7440.