Carthage Was Indeed Destroyed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C a Se Stud Y

This project is funded by the European Union November 2020 Culture in ruins The illegal trade in cultural property Case study: Algeria and Tunisia Julia Stanyard and Rim Dhaouadi Summary This case study forms part of a set of publications on the illegal trade in cultural property across North and West Africa, made up of a research paper and three case studies (on Mali, Nigeria and North Africa). This study is focused on Algeria and Tunisia, which share the same forms of material culture but very different antiquity markets. Attention is given to the development of online markets which have been identified as a key threat to this region’s heritage. Key findings • The large-scale extraction of cultural objects in both countries has its roots in the period of French colonial rule. • During the civil war in Algeria in the 1990s, trafficking in cultural heritage was allegedly linked to insurgent anti-government groups among others. • In Tunisia, the presidential family and the political elite reportedly dominated the country’s trade in archaeological objects and controlled the illegal markets. • The modern-day trade in North African cultural property is an interlinked regional criminal economy in which objects are smuggled between Tunisia and Algeria as well as internationally. • State officials and representatives of cultural institutions are implicated in the Algerian and Tunisian antiquities markets in a range of different capacities, both as passive facilitators and active participants. • There is evidence that some architects and real estate entrepreneurs are connected to CASE STUDY CASE trafficking networks. Introduction The region is a palimpsest of ancient material,7 much of which remains unexplored and unexcavated by Cultural heritage in North Africa has come under fire archaeologists. -

Stories of Ancient Rome Unit 4 Reader Skills Strand Grade 3

Grade 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Skills Strand Ancient Rome Ancient Stories of of Stories Unit 4 Reader 4 Unit Stories of Ancient Rome Unit 4 Reader Skills Strand GraDE 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

In Tunisia Policies and Legislations Related to the Democratic Transition

Policies and legislations The constitutional and legal framework repre- sents one of the most important signs of the related to the democratic transition in Tunisia. Especially by establishing rules, procedures and institutions in order to achieve the transition and its goals. Thus, the report focused on further operatio- nalization of the aforementioned framework democratic while seeking to monitor the events related to, its development and its impact on the transi- tion’s path. Besides, monitoring the difficulties of the second transition, which is related to the transition and political conflict over the formation of the go- vernment and what’s behind the scenes of the human rights official institutions. in Tunisia The observatorypolicies and rightshuman and legislation to democratic transition related . 27 Activating the constitutional and legal to submit their proposals until the end of January. Then, outside the major parties to be in the forefront of the poli- the committee will start its action from the beginning of tical scene. framework for the democratic transition February until the end of April 2020, when it submits its outcome to the assembly’s bureau. The constitution of 2015 is considered as the de facto framework for the democratic transition. And all its developments in the It is reportedly that the balances within the council have midst of the political life, whether in texts or institutions, are an not changed numerically, as it doesn’t witness many cases The structural and financial difficulties important indicator of the process of transition itself. of changing the party and coalition loyalties “Tourism” ex- The three authorities and the balance cept the resignation of the deputy Sahbi Samara from the of the Assembly Future bloc and the joining of deputy Ahmed Bin Ayyad to among them the Dignity Coalition bloc in the Parliament. -

Continuity of Culture: Romans in Pompeii Lesson Overview

Continuity of Culture: Romans in Pompeii Lesson Overview Unit: Lessons: 1. Grades 3 – 6 Continuity of Culture: Lesson One: Map study of 2. 5 -7 Class Periods Romans in Pompeii Italy. 3. Authors: Lori Howell, Lesson Two: History of Melody Nishinaga, Sarah Pompeii. Poku & Warren Soper Lesson Three: Pliny the 4. Social Sciences, Younger. English and History Lesson Four: Comparison of “Then and Now.” Lesson Five: Literature review. Lesson Six: Graphic Organizes. Lesson Seven: Writing Overview “A typical day in this town means going shopping, stopping by the laundry, catching a sporting event at the amphitheater, or maybe taking in a play – and that was 2000 years ago. “Can you guess where this is? Not where you might expect: You’re in ancient Pompeii, an Italian village where life came to a fiery halt when Mt. Vesuvius erupted in AD 79. “ -Discover Kids Pompeii Magazine 1 | Page The eruption of Vesuvius on August 24, 79 A.D. froze a moment in time under thick layers of ash and molten mud. It preserved elements of Roman culture that demonstrate the remarkable continuity of human life and history, proving that life in the past, even the far distant past, was remarkably similar to our own. In this lesson, by taking a closer look at the remains of Pompeii, students will gain a broad appreciation of people in the past. They will study Roman culture by locating Pompeii on a map, identifying important elements of its geography, and examining the remains of Pompeii to explain how the Ancient Romans in Pompeii are similar to people today. -

1 Classics 270 Economic Life of Pompeii

CLASSICS 270 ECONOMIC LIFE OF POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM FALL, 2014 SOME USEFUL PUBLICATIONS Annuals: Cronache Pompeiane (1975-1979; volumes 1-5) (Gardner: volumes 1-5 DG70.P7 C7) Rivista di Studi Pompeiani (1987-present; volumes 1-23 [2012]) (Gardner: volumes 1-3 DG70.P7 R585; CTP vols. 6-23 DG70.P7 R58) Cronache Ercolanesi: (1971-present; volumes 1-43 [2013]) (Gardner: volumes 1-19 PA3317 .C7) Vesuviana: An International Journal of Archaeological and Historical Studies on Pompeii and Herculaneum (2009 volume 1; others late) (Gardner: DG70.P7 V47 2009 V. 1) Notizie degli Scavi dell’Antichità (Gardner: beginning 1903, mostly in NRLF; viewable on line back to 1876 at: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000503523) Series: Quaderni di Studi Pompeiani (2007-present; volumes 1-6 [2013]) (Gardner: volumes 1, 5) Studi della Soprintendenza archeologica di Pompei (2001-present; volumes 1-32 [2012]) (Gardner: volumes 1-32 (2012)] Bibliography: García y García, Laurentino. 1998. Nova Bibliotheca Pompeiana. Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei Monografie 14, 2 vol. (Rome). García y García, Laurentino. 2012. Nova Bibliotheca Pompeiana. Supplemento 1o (1999-2011) (Rome: Arbor Sapientiae). McIlwaine, I. 1988. Herculaneum: A guide to Printed Sources. (Naples: Bibliopolis). McIlwaine, I. 2009. Herculaneum: A guide to Sources, 1980-2007. (Naples: Bibliopolis). 1 Early documentation: Fiorelli, G. 1861-1865. Giornale degli scavi. 31 vols. Hathi Trust Digital Library: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009049482 Fiorelli, G. ed. 1860-1864. Pompeianarum antiquitatum historia. 3 vols. (Naples: Editore Prid. Non. Martias). Laidlaw, A. 2007. “Mining the early published sources: problems and pitfalls.” In Dobbins and Foss eds. pp. 620-636. Epigraphy: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 4 (instrumentum domesticum from Vesuvian sites), 10 (inscriptions from various regions, including Campania). -

80808459.Pdf

Etude de la mise à 2x2 voies de la route RR27 entre Nabeul et Kélibia Etude d'Impact sur l’Environnement CHAPITRE 1. INTRODUCTION Le présent dossier constitue l'étude d'impact sur l'environnement du projet de la mise en 2x2 voies de la route de la RR27 entre Nabeul et Kélibia et la réalisation des déviations de Korba et Menzel Témime dans le gouvernorat de Nabeul. Les études techniques et d’EIE ont été confiées au bureau d'études B.T.E. (Bureau Tunisien des Etudes) par la Direction des Etudes du Ministère de l'Equipement. Ce projet est soumis aux dispositions de la loi n°88-91 du 2 août 1988 et notamment son article 5, ainsi qu'au décret n°91-362 de mars 1991 et au décret n°2005-1991 du 11 juillet 2005, qui précisent que la réalisation d'une étude d'impact sur l'environnement et son agrément par l'ANPE sont un préalable à toute autorisation de création d'activités nouvelles susceptibles d'engendrer des nuisances pour l'environnement. 1.1 CADRE GENERALE Le Cap Bon est un cap qui constitue la pointe nord-est de la Tunisie situé sur la mer méditerranée, il ouvre le canal de Sicile et ferme le golfe de Tunis. Appelé parfois « beau promontoire », les habitants connaissent cette péninsule sous le nom de Rass Eddar. À l'époque de la puissance de la civilisation carthaginoise, il constituerait la limite méridionale au-delà de laquelle ne peuvent plus circuler les navires romains. Le Cap Bon donne également son nom à toute la péninsule s'étendant jusqu'aux villes d'Hammamet (au sud) et de Soliman (à l'ouest). -

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 1

History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Lecture 18 Roman Agricultural History Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius View from the Tower of Mercury on the Pompeii city wall looking down the Via di Mercurio toward the forum 1 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Rome 406–88 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 241–27 BCE Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. Rome 193–211 Source: Harper Atlas of World History, 1992. 2 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Carthage Founded 814 BCE in North Africa Result of Phoenician expansion North African city-state opposite Sicily Mago, 350 BCE, Father of Agriculture Agricultural author wrote a 28 volume work in Punic, A language close to Hebrew. Roman Senate ordered the translation of Mago upon the fall of Carthage despite violent enmity between states. One who has bought land should sell his town house so that he will have no desire to worship the households of the city rather than those of the country; the man who takes great delight in his city residence will have no need of a country estate. Quotation from Columella after Mago Hannibal Capitoline Museums Hall of Hannibal Jacopo Ripanda (attr.) Hannibal in Italy Fresco Beginning of 16th century Roman History 700 BCE Origin from Greek Expansion 640–520 Etruscan civilization 509 Roman Republic 264–261 Punic wars between Carthage and Rome 3 History of Horticulture: Lecture 18 Roman Culture Debt to Greek, Egyptian, and Babylonian Science and Esthetics Roman expansion due to technology and organization Agricultural Technology Irrigation Grafting Viticulture and Enology Wide knowledge of fruit culture, pulses, wheat Legume rotation Fertility appraisals Cold storage of fruit Specularia—prototype greenhouse using mica Olive oil for cooking and light Ornamental Horticulture Hortus (gardens) Villa urbana Villa rustica, little place in the country Formal gardens of wealthy Garden elements Frescoed walls, statuary, fountains trellises, pergolas, flower boxes, shaded walks, terraces, topiary Getty Museum reconstruction of the Villa of the Papyri. -

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan -

Potential Use of Seaweeds in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) Diets

Potential use of seaweeds in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) diets Mensi F., Jamel K., Amor E.A. in Montero D. (ed.), Basurco B. (ed.), Nengas I. (ed.), Alexis M. (ed.), Izquierdo M. (ed.). Mediterranean fish nutrition Zaragoza : CIHEAM Cahiers Options Méditerranéennes; n. 63 2005 pages 151-154 Article available on line / Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse : -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- http://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=5600075 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- To cite this article / Pour citer cet article -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Mensi F., Jamel K., Amor E.A. Potential use of seaweeds in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) diets. In : Montero D. (ed.), Basurco B. (ed.), Nengas I. (ed.), Alexis M. (ed.), Izquierdo M. (ed.). Mediterranean fish nutrition. Zaragoza : CIHEAM, 2005. p. 151-154 (Cahiers Options Méditerranéennes; n. 63) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- http://www.ciheam.org/ http://om.ciheam.org/ Potential use of seaweeds in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) -

Restoration and Development Project of South Lake of Tunis and Its Shores

Restoration and Development Project of South Lake of Tunis and its Shores Environment Jan Vandenbroeck and Ben Charrada Rafik Restoration and Development Project of South Lake of Tunis and its Shores Abstract showed the presence of approximately 2 million m3 of organic sediment contaminated by heavy metals such This paper describes the development of the South as Chrome, Copper, Zinc, Iron, Nickel, Aluminium and Lake of Tunis which has recently been accomplished Hydrocarbons. Owing to this, the South Lake had by the group LAC SUD 2000 (a consortium of five reached a high level of pollution and eutrophication. The dredging contractors) at the request of the Tunisian extreme eutrophication conditions appear in summer Government. The project is within the framework of with dystrophic crises characterised by red water, bad the national development programme of the coastal smells and high mortality of fish life. Tunisian lagoons, in an effort to improve the living In order to solve these pollution conditions, the conditions in this area and to protect the environment “Societé d’Etudes et de Promotion de Tunis Sud” against the various forms of pollution which have (SEPTS) invited LAC SUD 2000 (a consortium of five affected it for more than half a century. contractors led by Dredging International) to carry out a large restoration and development programme during a It is amongst the rare projects which introduce viable period of three years. solutions for limiting the extent of pollution in one of the most eutrophic lagoons in the world. Considering The main objectives of this programme consisted of the location of the lake within the heart of the town of the creation of a flushing system of seawater by the Tunis City, the project will offer to Tunis centre an construction of an inlet and an outlet sluice driven by opening onto the sea, giving it a whole different look. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

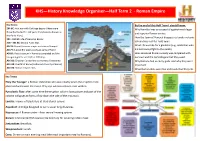

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

Women in Pompeii Author(S): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol

Women in Pompeii Author(s): Elizabeth Lyding Will Source: Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 5 (September/October 1979), pp. 34-43 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41726375 . Accessed: 19/03/2014 08:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 170.24.130.117 on Wed, 19 Mar 2014 08:08:22 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Wfomen in Pompeii by Elizabeth Lyding Will year 1979 marks the 1900th anniversary of the fatefulburial of Pompeii, Her- The culaneum and the other sitesengulfed by the explosion of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79. It was the most devastatingdisaster in the Mediterranean area since the volcano on Thera erupted one and a half millenniaearlier. The suddenness of the A well-bornPompeian woman drawn from the original wall in theHouse Ariadne PierreGusman volcanic almost froze the bus- painting of by onslaught instantly ( 1862-1941), a Frenchartist and arthistorian. Many tling Roman cityof Pompeii, creating a veritable Pompeianwomen were successful in business, including time capsule.