Hurricane Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Marine

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Marine Biology A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Kyle Zaffino December 2013 Thesis Committee: Professor Mark Haskell Smith, Co-Chairperson Professor Andrew Winer, Co-Chairperson Professor Elizabeth Crane Brandt Copyright by Kyle Zaffino 2013 The Thesis of Kyle Zaffino is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Table of Contents Bull Market 2 Regicide 4 Arc of the Covenant 13 Country Fried 24 Spring Forward 31 Whitecaps 40 Sabra 45 Braille 57 Pay it Backward 62 Angel Hair 77 Marine Biology 100 DOT 119 iv while we used long fingernails to carve epitaphs into the floor you were scratching freedom from concrete living in a world of gamblers and murder victims I walk these corridors knowing of the net beneath your defiance has become legend within these walls and we sit in our cells and hope you live enough life for the rest of us who did not make it out ~Scott Hull, Alcatraz Metaphors 1 Bull Market Park Tavern is a squat gray concrete box, slightly elevated above the south side of PA State Route 5. With its short pale walls and the sloped dirt parking lot, the establishment looks like a major league pitcher's mound, although in a ballpark the Budweiser and Coors signs are on the outfield walls rather than beckoning the fielders from within the rubber. The interior of the tavern is composed of darkly-varnished lumber, dotted here with a 26” LED television and there with a vintage bicycle in the rafters. -

Obie Trice, Body Guard F/ Dr Dre & Eminem

Obie Trice, Body Guard F/ Dr Dre & Eminem (Dr. Dre) Yeah, yo lets bring it (Chorus)(Eminem) What you gonna do when shit hits the fan Are you gonna stand and fight like a man Will u be as hard as you say you are Or you gonna run and go get your body guard I said What you gonna do when shit hits the fan Are you gonna stand and fight like a man Show us you as hard as you say you are Or you gonna run and go get your body guard (Dr. Dre) Niggas is so gangsta, niggas is thugs niggas'll spend their whole life battlin' drugs slangin dope and hopes of one day bein able to own they own label and give the game up some niggas came up and some just didnt its just the way it is if it aint minute just isn't some niggas'll get money and pay niggas to back em so they can act up feel comfortable an rap tough and thats ass backwards them niggas'll keep comin back and thats when extortion happens to the struggle to get free I know how this shit be you give anything that look legitimately but you gonna find if you do get in this industry that its best to do bussiness with me then against me niggas get behind mics and aint even emcees niggas get on mtv just to diss me this shit dont even piss me off I'm laughing all the way to the bank watching you saddle life in my bentley you niggas aint even got a car you're so far under my radar I dont even know who the fuck you are To tell you to suck my dick while im pissing I dont even listen to ya shit to know who the fuck im dissing and media just feeds into these feuds trying to add fuel to the fire this little nigga -

So You've Been Musically Shamed

WILLIAM CHENG Dartmouth College Email: [email protected] So You’ve Been Musically Shamed ABSTRACT In July 2014, an anonymous source leaked the raw audio of Britney Spears’s confessional ballad “Alien.” Haters pounced on this star’s denuded voice, gleefully seizing on the viral artifact as a smoking gun for Spears’s deficits and for the pop industry’s artistic fakeries more broadly. My paper situates this flashpoint of Spears-shaming within late-capitalist archives of public humiliation, cyberleaks, and the paternalistic scrutiny of women’s bodies and voices. KEYWORDS: critical theory, media studies, popular music A marketplace has emerged where public humiliation is a commodity and shame is an industry. How is the money made? Clicks. The more shame, the more clicks. – monica lewinsky1 “Poor Britney Spears” is not the beginning of a sentence you hear often uttered in my household. – tony hoagland, “poor britney spears,” beginning of the poem2 In the summer of 2014, the internet sprang a musical leak. Suddenly circulating on YouTube was a video featuring the allegedly raw, non-Auto-Tuned sounds of Brit- 3 ney Spears singing her new album track “Alien.” Spears’s voice in this recording was noticeably off-key and off-kilter, like some abject artifact meant to be overwritten, for- gotten, abandoned on the cutting room floor. In the video’s comment threads, view- ers’ strident pronouncements of aching ears and melting brains swirled in a chorus of mockery. Haters pounced on the star’s denuded voice and offered it as airtight 1. Monica Lewinsky, “The Price of Shame,” TED Talks (2015), transcript available at http://www.ted.com/ talks/monica_lewinsky_the_price_of_shame/transcript?language=en. -

You Have +1000 CP

Welcome to the world of Deadbolt, an eerie locale of monsters, magic, and general mayhem. The atmosphere’s a bit depressing but you shouldn’t be too bored; there’s a prime 80s nightlife and the city never sleeps. Unfortunately, neither do the corpses and that’s starting to become a bit of a problem. Residual magic has a nasty habit of bringing the dead back to life. This usually wouldn’t be an issue for the local peacekeepers, but as of late they’ve noticed that the undead have been getting a bit more… organized. No less than four gangs have sprung up seemingly out of nowhere, all answering to an entity know only as “Ibzan”. Now normally, the candles would have had a reaper on standby to take care of this mess, but it seems your ‘benefactor’ thought it would be funny to have you take their place. It’s up to you if you want to do anything about it, but just keep in mind that whatever this guy’s doing involves corpses, lots and lots of corpses. Either way, this isn’t exactly the place you want to dive into blind… You have +1000 CP. Species Your age, sex, and history don’t really matter here. You’ll wake up in an old apartment with no memories of your time alive. Probably for the best. Zombie (Free) Your garden-variety flesh-eaters. Not exactly known for their intellect and cunning, but the big ones make good meatshields. The Zombie Kingz are shacked up in a web of dingy apartment buildings. -

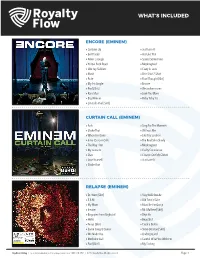

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

Prepare Now, Part I: How to Be Ted Kaczynski Without All That Unabomber Crap

1 PREPARE NOW, PART I: HOW TO BE TED KACZYNSKI WITHOUT ALL THAT UNABOMBER CRAP s you may have learned from my fi rst book, I was once a Webelo— that’s right, not a Boy Scout, but a Webelo. Pretty low on the sur- A vival skills totem pole, but at least it was a step up from the Cub Scouts. Anyhow, before I was ejected from this society for chucking a can of soda at my scoutmaster’s head, we went on a few camping trips. These consisted of about twenty of us kids, and fi ve or six parents, all of whom were stupid enough to get duped into taking care of twenty boys in the wilderness. I would like to say that I learned all sorts of practical knowl- edge on these outings that I could pass on to you, but of course the parents ended up putting up the tent and doing all the merit-badge-worthy tasks we kids were supposed to do. However, I did learn a few lessons from these experiences, the most important being that the wilderness sucks. If you 027-44914_ch01_4P.indd 27 6/24/10 4:00:23 PM 28 FORREST GRIFFIN have a house with hot water, you should probably stay there because the wild will do everything in its power to make you absolutely miserable. On the second day of one of these little adventures into the great unknown, the parents gathered up all the kids, brought us down to a luke- warm creek, and expected us to bathe. -

Feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77

01. 50 Cent - Intro (0:06) 75. Ace Of Base - Life Is A Flower (3:44) 02. 50 Cent - What Up Gangsta? (2:59) 76. Ace Of Base - C'est La Vie (3:27) 03. 50 Cent - Patiently Waiting (feat. Eminen) (4:48) 77. Ace Of Base - Lucky Love (Frankie Knuckles Mix) 04. 50 Cent - Many Men (Wish Death) (4:16) (3:42) 05. 50 Cent - In Da Club (3:13) 78. Ace Of Base - Beautiful Life (Junior Vasquez Mix) 06. 50 Cent - High All the Time (4:29) (8:24) 07. 50 Cent - Heat (4:14) 79. Acoustic Guitars - 5 Eiffel (5:12) 08. 50 Cent - If I Can't (3:16) 80. Acoustic Guitars - Stafet (4:22) 09. 50 Cent - Blood Hound (feat. Young Buc) (4:00) 81. Acoustic Guitars - Palosanto (5:16) 10. 50 Cent - Back Down (4:03) 82. Acoustic Guitars - Straits Of Gibraltar (5:11) 11. 50 Cent - P.I.M.P. (4:09) 83. Acoustic Guitars - Guinga (3:21) 12. 50 Cent - Like My Style (feat. Tony Yayo (3:13) 84. Acoustic Guitars - Arabesque (4:42) 13. 50 Cent - Poor Lil' Rich (3:19) 85. Acoustic Guitars - Radiator (2:37) 14. 50 Cent - 21 Questions (feat. Nate Dogg) (3:44) 86. Acoustic Guitars - Through The Mist (5:02) 15. 50 Cent - Don't Push Me (feat. Eminem) (4:08) 87. Acoustic Guitars - Lines Of Cause (5:57) 16. 50 Cent - Gotta Get (4:00) 88. Acoustic Guitars - Time Flourish (6:02) 17. 50 Cent - Wanksta (Bonus) (3:39) 89. Aerosmith - Walk on Water (4:55) 18. -

The Authenticity of a Rapper: the Lyrical Divide Between Personas

The Authenticity of a Rapper: The Lyrical Divide Between Personas and Persons by Hannah Weiner A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2014 © March 25, 2014 Hannah Weiner Acknowledgements The past year has been dedicated to listening to countless hours of rap music, researching hip hop blogs, talking to everyone who will listen about exciting ideas about Kanye West, and, naturally, writing. Many individuals have provided assistance that helped an incredible amount during the process of writing and researching for this thesis. Firstly, I am truly indebted to my advisor, Macklin Smith. This thesis would not be nearly as thorough in rap’s historical background or in hip hop poetics without his intelligent ideas. His helpfulness with drafts, inclusion of his own work in e-mails, and willingness to meet over coffee not only deepened my understanding of my own topic, but also made me excited to write and research hip hop poetics. I cannot express how much I appreciated his feedback and flexibility in working with me. I am also grateful for Gillian White’s helpfulness throughout the writing process, as well. After several office hours and meetings outside of class, she has offered invaluable insight into theories on sincerity and the “personal,” and provided me with numerous resources that helped form many of the ideas expressed in my argument. I thank my family for supporting me and offering me hospitality when the stresses of thesis writing overwhelmed me on campus. They have been supportive and a source of love and compassion throughout this process and the past 21 years, as well. -

234 MOTION for Permanent Injunction.. Document Filed by Capitol

Arista Records LLC et al v. Lime Wire LLC et al Doc. 237 Att. 12 EXHIBIT 12 Dockets.Justia.com CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LLP WORLDWIDE PLAZA ROBERT O. JOFFE JAMES C. VARDELL, ID WILLIAM J. WHELAN, ffl DAVIDS. FINKELSTEIN ALLEN FIN KELSON ROBERT H. BARON 825 EIGHTH AVENUE SCOTT A. BARSHAY DAVID GREENWALD RONALD S. ROLFE KEVIN J. GREHAN PHILIP J. BOECKMAN RACHEL G. SKAIST1S PAULC. SAUNOERS STEPHEN S. MADSEN NEW YORK, NY IOOI9-7475 ROGER G. BROOKS PAUL H. ZUMBRO DOUGLAS D. BROADWATER C. ALLEN PARKER WILLIAM V. FOGG JOEL F. HEROLD ALAN C. STEPHENSON MARC S. ROSENBERG TELEPHONE: (212)474-1000 FAIZA J. SAEED ERIC W. HILFERS MAX R. SHULMAN SUSAN WEBSTER FACSIMILE: (212)474-3700 RICHARD J. STARK GEORGE F. SCHOEN STUART W. GOLD TIMOTHY G. MASSAD THOMAS E. DUNN ERIK R. TAVZEL JOHN E. BEERBOWER DAVID MERCADO JULIE SPELLMAN SWEET CRAIG F. ARCELLA TEENA-ANN V, SANKOORIKAL EVAN R. CHESLER ROWAN D. WILSON CITYPOINT RONALD CAM I MICHAEL L. SCHLER PETER T. BARBUR ONE ROPEMAKER STREET MARK I. GREENE ANDREW R. THOMPSON RICHARD LEVIN SANDRA C. GOLDSTEIN LONDON EC2Y 9HR SARKIS JEBEJtAN DAMIEN R. ZOUBEK KRIS F. HEINZELMAN PAUL MICHALSKI JAMES C, WOOLERY LAUREN ANGELILLI TELEPHONE: 44-20-7453-1000 TATIANA LAPUSHCHIK B. ROBBINS Kl ESS LING THOMAS G. RAFFERTY FACSIMILE: 44-20-7860-1 IBO DAVID R. MARRIOTT ROGER D. TURNER MICHAELS. GOLDMAN MICHAEL A. PASKIN ERIC L. SCHIELE PHILIP A. GELSTON RICHARD HALL ANDREW J. PITTS RORYO. MILLSON ELIZABETH L. GRAYER WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL NUMBER MICHAEL T. REYNOLDS FRANCIS P. BARRON JULIE A. -

What Are Idioms?

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62973-4 — English Idioms in Use Advanced Book with Answers 2nd Edition Excerpt More Information 1 What are idioms? A Formulaic language Idioms are a type of formulaic language. Formulaic language consists of fixed expressions which you learn and understand as units rather than as individual words, for example: type of formulaic language examples greetings and good wishes Hi there! See you soon! Happy birthday! prepositional phrases at the moment, in a hurry, from time to time sayings, proverbs and quotations It’s a small world! Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. To be or not to be – that is the question. compounds car park, bus stop, home-made phrasal verbs take off, look after, turn down collocations blonde hair, deeply disappointed B Idioms Idioms are fixed combinations of words whose meaning is often difficult to guess from the meaning of each individual word. For example, if I say ‘I put my foot in it the other day at Linda’s house – I asked her if she was going to marry Simon’, what does it mean? If you do not know that put your foot in it means say something accidentally which upsets or embarrasses someone, it is difficult to know exactly what the sentence means. It has a non-literal or idiomatic meaning. Idioms are constructed in different ways, and this book gives you practice in a wide variety of types of idiom. Here are some examples: Tim took a shine to [immediately liked] his teacher. (verb + object + preposition) The band’s number one hit was just a flash in the pan [something that happens only once] (idiomatic noun phrase) Little Jimmy has been as quiet as a mouse [extremely quiet] all day. -

Redefining Health & Wellness

Redefining Health & Wellness #26 Featured this episode: Shohreh Davoodi Shohreh Davoodi: I have Episode 26 of the Redefining Health & Wellness podcast coming right up. It is a short and sweet solo episode with yours truly. Since this is the time of New Year’s resolutions and goal setting, today I want to give y’all some of my favorite tips for setting effective goals, whether in the new year, or any time at all. To access the show notes and a full transcript of this episode, head to shohrehdavoodi.com/26. That's shohrehdavoodi.com/26. [Music plays] Hey y’all, welcome to the Redefining Health & Wellness podcast. I’m your host, Shohreh Davoodi. I’m a certified intuitive eating counselor, and a certified personal trainer. I help people improve their relationships with exercise, food, and their bodies, so they can ditch diet culture for good, and do what feels right for them. Through this podcast I want to give you the tools to redefine what health and wellness mean to you. By exposing myths and misconceptions, delving into all the areas of health that often get ignored, and reminding you that health and wellness are not moral obligations. Are you ready? Let’s fuck some shit up. We have officially made it to the final Redefining Health & Wellness podcast episode of the year 2019, and also the decade. Even though that feels really weird to say when I only started this podcast five months ago, but technically it’s true. So, we’re going with it and if you are listening to this episode on the day it drops, it also New Year’s Eve, so the very last day of the year, which means that now is the time of year for reflecting, and goal setting, and of course, new year’s resolutions. -

Eminem the Complete Guide

Eminem The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 01 Feb 2012 13:41:34 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Eminem 1 Eminem discography 28 Eminem production discography 57 List of awards and nominations received by Eminem 70 Studio albums 87 Infinite 87 The Slim Shady LP 89 The Marshall Mathers LP 94 The Eminem Show 107 Encore 118 Relapse 127 Recovery 145 Compilation albums 162 Music from and Inspired by the Motion Picture 8 Mile 162 Curtain Call: The Hits 167 Eminem Presents: The Re-Up 174 Miscellaneous releases 180 The Slim Shady EP 180 Straight from the Lab 182 The Singles 184 Hell: The Sequel 188 Singles 197 "Just Don't Give a Fuck" 197 "My Name Is" 199 "Guilty Conscience" 203 "Nuttin' to Do" 207 "The Real Slim Shady" 209 "The Way I Am" 217 "Stan" 221 "Without Me" 228 "Cleanin' Out My Closet" 234 "Lose Yourself" 239 "Superman" 248 "Sing for the Moment" 250 "Business" 253 "Just Lose It" 256 "Encore" 261 "Like Toy Soldiers" 264 "Mockingbird" 268 "Ass Like That" 271 "When I'm Gone" 273 "Shake That" 277 "You Don't Know" 280 "Crack a Bottle" 283 "We Made You" 288 "3 a.m." 293 "Old Time's Sake" 297 "Beautiful" 299 "Hell Breaks Loose" 304 "Elevator" 306 "Not Afraid" 308 "Love the Way You Lie" 324 "No Love" 348 "Fast Lane" 356 "Lighters" 361 Collaborative songs 371 "Dead Wrong" 371 "Forgot About Dre" 373 "Renegade" 376 "One Day at a Time (Em's Version)" 377 "Welcome 2 Detroit" 379 "Smack That" 381 "Touchdown" 386 "Forever" 388 "Drop the World"