Constructive Possession and Constructive Delivery in Transfer of Title to Goods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 1 of 61 FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT DAVID CASSIRER; AVA CASSIRER; No. 15-55550 UNITED JEWISH FEDERATION OF SAN 15-55977 DIEGO COUNTY, a California non- profit corporation, D.C. No. Plaintiffs-Appellees, 2:05-cv-03459- JFW-E v. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION FOUNDATION, an agency or instrumentality of the Kingdom of Spain, Defendant-Appellant. DAVID CASSIRER; AVA CASSIRER; No. 15-55951 UNITED JEWISH FEDERATION OF SAN DIEGO COUNTY, a California non- D.C. No. profit corporation, 2:05-cv-03459- Plaintiffs-Appellants, JFW-E v. OPINION THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION FOUNDATION, an agency or instrumentality of the Kingdom of Spain, Defendant-Appellee. Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 2 of 61 2 CASSIRER V. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California John F. Walter, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted December 5, 2016 Pasadena, California Filed July 10, 2017 Before: Consuelo M. Callahan, Carlos T. Bea, and Sandra S. Ikuta, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge Bea Case: 15-55550, 07/10/2017, ID: 10502017, DktEntry: 127-1, Page 3 of 61 CASSIRER V. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION 3 SUMMARY* Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act / Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act The panel reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment, on remand, in favor of Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation, the defendant in an action under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act concerning a Camille Pissarro painting that was forcibly taken from the plaintiffs’ great-grandmother by an art dealer who had been appointed by the Nazi government to conduct an appraisal. -

Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Sticks

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2016 Patent Transfer And The Bundle of Sticks Andrew Michaels The George Washington University Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michaels, Andrew C., Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Sticks (December 1, 2016). GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 2016-57; GWU Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2016-57. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2883829 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrew C. Michaels Patent Transfer DRAFT – Dec. 2016 Patent Transfer And The Bundle of Sticks by Andrew C. Michaels* Abstract In the age of the patent troll, patents are often licensed and transferred. A transferred patent may have been subject to multiple complex license agreements. It cannot be that such a transfer wipes the patent clean of all outstanding license agreements; the licensee must keep the license. But at the same time, it cannot be that the patent transferee becomes a party to a complex and sweeping license agreement – the contract – merely by virtue of acquiring one patent. This article attempts to separate the in personam aspects of a license agreement from its effects on the underlying in rem patent rights, using Hohfeld’s framework of jural relations and the “bundle of sticks” conception of property. -

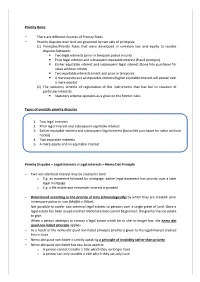

Priority Rules

Priority Rules − There are different Sources of Priority Rules − Priority disputes over land are governed by two sets of principles: (1) Principles/Priority Rules that were developed in common law and equity to resolve disputes between: ▪ Two legal interests (prior in tempore potior in iure) ▪ Prior legal interest and subsequent equitable interest (fraud principle) ▪ Earlier equitable interest and subsequent legal interest (bona fide purchaser for value without notice) ▪ Two equitable interests (merit and prior in tempore) ▪ A mere equity and an equitable interest (higher equitable interest will prevail over a mere equity) (2) The statutory scheme of registration of the instruments that has led to creation of particular interests: ▪ Statutory scheme operates as a gloss on the former rules Types of possible priority disputes 1. Two legal interests 2. Prior legal interest and subsequent equitable interest 3. Earlier equitable interest and subsequent legal interest (bona fide purchaser for value without notice) 4. Two equitable interests 5. A mere equity and an equitable interest Priority Disputes – Legal interests v Legal interests – Nemo Dat Principle − Two non-identical interest may be created in land o E.g. an easement followed by mortgage: earlier legal easement has priority over a later legal mortgage o E.g. a life estate and remainder interest is granted − Determined according to the priority of time (chronologically) by which they are created: prior in tempore potior in iure (Moffet v Dillon). − Not possible to confer two identical legal estates to persons over a single piece of land. Once a legal estate has been issued another identical estate cannot be granted: the grantor has no estate to give. -

![[1] the Basics of Property Division](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2246/1-the-basics-of-property-division-1212246.webp)

[1] the Basics of Property Division

RESTATEMENT OF THE LAW FOURTH, PROPERTY PROJECTED OVERALL TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME [1] THE BASICS OF PROPERTY DIVISION ONE: DEFINITIONS Chapter 1. Meanings of “Property” Chapter 2. Property as a Relation Chapter 3. Separation into Things Chapter 4. Things versus Legal Things Chapter 5. Tangible and Intangible Things Chapter 6. Contracts as Property [pointers to Contracts Restatement and UCC] Chapter 7. Property in Information [pointer to Intellectual Property Restatement(s)] Chapter 8. Entitlement and Interest Chapter 9. In Rem Rights Chapter 10. Residual Claims Chapter 11. Customary Rights Chapter 12. Quasi-Property DIVISION TWO: ACCESSION Chapter 13. Scope of Legal Thing Chapter 14. Ad Coelum Chapter 15. Airspace Chapter 16. Minerals Chapter 17. Caves Chapter 18. Accretion, etc. [cross-reference to water law, Vol. 2, Ch. 2] Chapter 19. Fruits, etc. Chapter 20. Fixtures Chapter 21. Increase Chapter 22. Confusion Chapter 23. Improvements DIVISION THREE: POSSESSION Chapter 24. De Facto Possession Chapter 25. Customary Legal Possession Chapter 26. Basic Legal Possession Chapter 27. Rights to Possess Chapter 28. Ownership versus Possession Chapter 29. Transitivity of Rights to Possess Chapter 30. Sequential Possession, Finders Chapter 31. Adverse Possession Chapter 32. Adverse Possession and Prescription Chapter 33. Interests Not Subject to Adverse Possession Chapter 34. State of Mind in Adverse Possession xvii © 2016 by The American Law Institute Preliminary draft - not approved Chapter 35. Tacking in Adverse Possession DIVISION FOUR: ACQUISITION Chapter 36. Acquisition by Possession Chapter 37. Acquisition by Accession Chapter 38. Specification Chapter 39. Creation VOLUME [2] INTERFERENCES WITH, AND LIMITS ON, OWNERSHIP AND POSSESSION Introductory Note (including requirements of possession) DIVISION ONE: PROPERTY TORTS Chapter 1. -

Appendix C to the Brief to the Court (Protection of Indigenous

SKELETON ARGUMENT OF THE CLAIMANTS APPENDIX C: PROTECTION OF INDIGENOUS CUSTOMARY PROPERTY RIGHTS BY THE COMMON LAW I. The common law has long recognized and protected property rights arising out of pre-existing customary land tenure systems 1. A feature of common law jurisdictions throughout the world is that legally enforceable rights in land may exist on the basis of longstanding use or occupancy.1 In this century alone, Maya people have continuously used and occupied the lands in the areas where their villages are located in southern Belize, for periods far in excess of the ordinarily applicable period for establishing property rights against the Crown or private subjects on the basis of adverse possession.2 2. However, the claimants need not rely on adverse possession in order to establish their property rights. Long before the emergence of the contemporary human rights system at the international level, the British common law included as a central tenet that rights arising out of customary law and usages of a territory that pre-exist the reception of the common law into that territory, continue to be protected and incorporated into the common law.3 As articulated by the Privy Council, the common law has always required … that the rights of property of the inhabitants were to be fully respected. This principle is a usual one under British policy and law when such occupations take place. ... it is not admissible to conclude that the Crown is, generally speaking, entitled to the beneficial ownership of the land as having so passed to the Crown as to displace any presumptive title of the natives.4 3. -

Curing an Improper Tender of Title to Chattels: Past, Present and Commercial Code William D

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1962 Curing an Improper Tender of Title to Chattels: Past, Present and Commercial Code William D. Hawkland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hawkland, William D., "Curing an Improper Tender of Title to Chattels: Past, Present and Commercial Code" (1962). Minnesota Law Review. 2555. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2555 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 697 Curing an Improper Tender of Title to Chattels: Past, Present and Commercial Code Stolen and encumbered chattels constitute a significant portion of the goods moving in commerce. In order to protect 1the original owners of the goods against the claims of bona fide purchasers, the doctrines of "caveat emptor" and "nemo dat quod non habet" developed in the common law and have been carried into the Uni- form Sales Act. In this Article Professor Hawkland sug- gests that the premises underlying these concepts need to be re-examined and that the concepts themselves should be reformulated to more fairly allocate among original owners, dealers, and purchasers the risks arising when stolen or encumbered goods are sold; one inadvertently dealing in this type of goods needs added protection against "bad faith surprise rejections of title." Profes- sor Hawkland concludes that the Uniform Commercial Code's adoption of the concept of "cure" affords the deal- er a potent weapon against such "bad faith" claims and constitutes a major stride forward toward fairer and more realistic treatment of this problem. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 18-1392 IN THE Supreme Court of tfje ®mteb H>tate£ JOHN BARONE Petitioner, v. WELLS FARGO BANK N.A., Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit PETITION FOR REHEARING John Barone PO Box 5193 Lighthouse Point, FL 33074 954-644-9900 - Pro Se Petitioner RECEIVED JUL 1 5 2019 OFFICE OF THE CLERK SUPREME COURT lift 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.......................... i PETITION FOR REHEARING..................... 1 REASONS FOR GRANTING REHEARING 1 I. Wells Fargo With Broward Foreclosure Court Assistance Continues Its RICO Schemes and Harassment of Mr. Barone and His Family, Has Unlawfully Set a New Sale Date and Has Failed To Respond To Its Foreclosure Cancellation Notice In Which It Has Updated Credit Reports to Remove Foreclosure 4 II. Fannie Mae and Wells Fargo Treasury Agree ment Substantiates The Government’s Involve ment In Countless Wrongful Foreclosures......6 III. Wells Fargo was NEVER a UCC Article 3 Holder, Failed To Comply With FL Law and De liberately Provided Misleading Information To The District Court 7 CONCLUSION.............................................................. 9 CERTIFICATE OF PRO SE PARTY.......................... 10 APPENDIX Wells Fargo Credit Reporting Notice of Foreclosure Cancelation (Aug. 6th> 2018).................... Appx.l TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Page(s) Bankers Trust (Delaware) v. 236 Beltway Inv., 865 F. Supp. 1186, 1195 (E.D. Va. 1994) 7 Bein v. Heath, 6 How. 228, 247, 12 L.Ed. 416 (1848)... 9 Carpenter v. Longan, 83 U.S. 271 (1872).................. 9 Dept, of Transportation v. Assoc. ofAmer. Railroads, 135 S. -

Andrew C. Michaels Patent Transfer 83 Brooklyn L. Rev. (2018) I

Andrew C. Michaels Patent Transfer 83 Brooklyn L. Rev. _ (2018) Patent Transfer And The Bundle Of Sticks by Andrew C. Michaels* Abstract When patents subject to a license agreement are transferred, to what extent do the benefits and burdens of the license agreement run with the patent? Courts have stated that those aspects of the agreement relating to “actual use” of the patent or invention are encumbrances running with the transferred patent. But this doctrinal test is not consistently applied and is not up to the task of clearly and consistently delineating the extent to which patent license agreements run with transferred patents. The question is one of separating an in personam license agreement from the agreement’s effects on underlying in rem intellectual property rights. Conceptualizing the patent as a bundle of rights to exclude and employing Hohfeld’s jural relations, this article proposes a more coherent framework for analyzing the extent to which actions by a prior patent owner run with a transferred patent to affect the rights of subsequent owners. The patent owner, through a license agreement or other actions such as selling a patented article, may exchange sticks in the bundle for other forms of value, thus diminishing the size of the in rem bundle of rights. When a patent is transferred, what is transferred is whatever remains in the in rem patent bundle, while the in personam contract remains between the two signatories. The broader contribution of this article is in exploring how Hohfeld’s platform can usefully aid in the analysis of complex doctrinal issues in patent law, particularly issues that arise from the transfer of patents. -

The Elements of Possession

The Elements of Possession Henry E. Smith* April 16, 2014 Abstract Property rights in the New Institutional Economics correspond variously to facto possession, legal possession, and ownership. This paper offers a bottom-up account of possession that builds on salience based-accounts of conventions and on the NIE approach to property rights. Possession is a first cut at a legal ontology in an overall modular architecture of property. The legal ontology divides the world up into persons and things, and establishes associations between persons and things. These associations will be in the interest of use, and so possession will usually require stylized duties of abstention on the part of other potential users. Depending on the nature of the group, the resources, and the universe of possible uses, duties of abstention can be implemented though norms of exclusion or governance of particular uses. What counts as a “thing” emerges from a combination of possession and accession, and so these aspects of property form a basic module, which serves as a basic default regime that can be displaced by more refined rules of title and governance. Possessory customs tend to be formalized into law, and yet for reasons of information cost, basic notions of possession retain their importance in many, especially informal, contexts. From the basic modular architecture many of the puzzling features of possession receive an explanation. Introduction Possession is both mundane and mysterious. The notion of possession governs most people’s relation to most things most of the time. From seats at a theater to the clothes on one’s back, possession and its stability are a basic fact of life – or one of the most sorely missed aspects of social order. -

Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Rights Andrew C

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 83 Article 3 Issue 3 Spring 6-1-2018 Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Rights Andrew C. Michaels Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Andrew C. Michaels, Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Rights, 83 Brook. L. Rev. (2018). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol83/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. Patent Transfer and the Bundle of Rights Andrew C. Michaels† INTRODUCTION When patents subject to a license agreement are transferred, to what extent do the benefits and burdens of the license agreement run with the patent? This question involves separating the in personam contract from its effect on underlying in rem intellectual property rights. But this theoretical question is of some contemporary practical significance. Consider the patent troll.1 The bête noire of the patent law community,2 the troll lies in wait under technological bridges, until it emerges threatening to cast its prey into a † Visiting Associate Professor of Law and Frank H. Marks Intellectual Property Fellow, George Washington University Law School. J.D., New York University School of Law. For helpful comments, the author particularly thanks Henry Smith, John Duffy, Katherine Strandburg, Barton Beebe, Jason Rantanen, Robert Brauneis, Michael Abramowicz, Dmitry Karshtedt, Shubha Ghosh, Joshua Sarnoff, Joseph Sanders, Emily Berman, and Eric Clayes, as well as those who participated in the 2016 Mid-Atlantic Works-in-Progress Colloquium at American University Washington College of Law, the 2017 Works-in-Progress in IP conference at Boston University School of Law, the 2017 JSIP conference at Michigan State University College of Law, and the 2017 IP roundtable at Texas A&M University School of Law, and finally, the editors of the Brooklyn Law Review. -

Nemo Dat & Its Exceptions Under Subsection 26(1.2)

ABCD Remoteness Problems: Nemo Dat & Its Exceptions Under Subsection 26(1.2) of Saskatchewan’s The Sale of Goods Act Clayton Bangsund* I would have been out here a little bit sooner, but they gave me the wrong dressing room, and I couldn’t find any place to put my stuff. And I don’t know how you are, but I need a place to put my stuff. So that’s what I’ve been doing 2018 CanLIIDocs 365 back there—just trying to find a place for my stuff. You know how important that is. That’s the whole meaning of life, isn’t it? Trying to find a place for your stuff. George Carlin Universal Amphitheatre Los Angeles, California, 19861 * Assistant Professor, University of Saskatchewan, College of Law. I am thankful to Professors Ronald C.C. Cuming, Tamara Buckwold, Mohamed Khimji, Thomas Telfer and Roderick J. Wood, and all others in attendance at the Second Annual Commercial Law Symposium held in Saskatoon in the fall of 2017, for your insight and constructive feedback. Thanks also to Marek Coutu for your valuable research assistance. Finally, I am grateful to the Law Foundation for funding this research. 1 “Stuff”, online: Youtube <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4x_QkGPCL18>, archived: <https://perma.cc/7GUH-TPFH> (clip taken from 1986 Comic Relief) [Carlin, “Stuff”]. Carlin introduced this material during the live component of an album titled A Place for My Stuff (Atlantic, 1981). In his memoir, Carlin explained that the “stuff” routine “eventually became a signature piece” for his next generation of material. -

UCC Article 9, Filing-Based Authority, and Fundamental Property Principles

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 9-1-2013 U.C.C. Article 9, Filing-Based Authority, and Fundamental Property Principles: A Reply to Professor Plank Steven L. Harris Chicago-Kent Collegel of Law Charles W. Mooney Jr. University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Harris, Steven L. and Mooney, Charles W. Jr., "U.C.C. Article 9, Filing-Based Authority, and Fundamental Property Principles: A Reply to Professor Plank" (2013). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 1014. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1014 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 3058-182-02Harris-1pass-r02.3d Pages: [1–14] Date: [November 4, 2013] Time: [19:37] U.C.C. Article 9, Filing-Based Authority, and Fundamental Property Principles: A Reply to Professor Plank By Steven L. Harris and Charles W. Mooney, Jr.* Uniform Commercial Code Article 9 generally follows the common-law principle that one cannot give rights in property that one does not have (nemo dat quod non habet). In many circumstances, however, Article 9’s priority rules, including its rule awarding priority to the first security interest that is perfected or as to which a financ- ing statement has been filed, trump nemo dat and enable a debtor to grant a senior security interest in property that the debtor previously had encumbered.