Transform—Don't Just Tinker With—Legal Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marking 200 Years of Legal Education: Traditions of Change, Reasoned Debate, and Finding Differences and Commonalities

MARKING 200 YEARS OF LEGAL EDUCATION: TRADITIONS OF CHANGE, REASONED DEBATE, AND FINDING DIFFERENCES AND COMMONALITIES Martha Minow∗ What is the significance of legal education? “Plato tells us that, of all kinds of knowledge, the knowledge of good laws may do most for the learner. A deep study of the science of law, he adds, may do more than all other writing to give soundness to our judgment and stability to the state.”1 So explained Dean Roscoe Pound of Harvard Law School in 1923,2 and his words resonate nearly a century later. But missing are three other possibilities regarding the value of legal education: To assess, critique, and improve laws and legal institutions; To train those who pursue careers based on legal training, which may mean work as lawyers and judges; leaders of businesses, civic institutions, and political bodies; legal academics; or entre- preneurs, writers, and social critics; and To advance the practice in and study of reasoned arguments used to express and resolve disputes, to identify commonalities and dif- ferences, to build institutions of governance within and between communities, and to model alternatives to violence in the inevi- table differences that people, groups, and nations see and feel with one another. The bicentennial of Harvard Law School prompts this brief explo- ration of the past, present, and future of legal education and scholarship, with what I hope readers will not begrudge is a special focus on one particular law school in Cambridge, Massachusetts. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ∗ Carter Professor of General Jurisprudence; until July 1, 2017, Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor, Harvard Law School. -

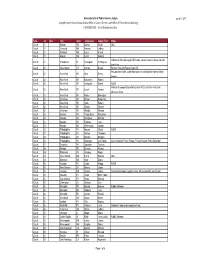

Anecdotal List of Public Interest Judges Compiled by the Harvard

Anecdotal List of Public Interest Judges as of 11/3/17 Compiled by the Harvard Law School Office of Career Services and Office of Public Interest Advising. CONFIDENTIAL - for HLS Applicants Only Type Cir Dist City State Judge Last Judge First Notes Circuit 01 Boston MA Barron David OLC Circuit 01 Concord NH Howard Jeffrey Circuit 01 Portland ME Lipez Kermit Circuit 01 Boston MA Lynch Sandra Worked at Harvard Legal Aid Bureau; started career in legal aid and Circuit 01 Providence RI Thompson O. Rogeree family law Circuit 02 New Haven CT Carney Susan Former Yale and Peace Corps GC Has partnered with Judge Katzmann on immigration representation Circuit 02 New York NY Chin Denny project Circuit 02 New York NY Katzmann Robert Circuit 02 New York NY Livingston Debra AUSA Worked as cooperating attorney with ACLU and New York Civil Circuit 02 New York NY Lynch Gerard Liberties Union Circuit 02 New York NY Parker Barrington Circuit 02 Syracuse NY Pooler Rosemary Circuit 02 New York NY Sack Robert Circuit 02 New York NY Straub Chester Circuit 02 Geneseo NY Wesley Richard Circuit 03 Newark NJ Trump Barry Maryanne Circuit 03 Newark NJ Chagares Michael Circuit 03 Newark NJ Fuentes Julio Circuit 03 Newark NJ Greenaway Joseph Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Krause Cheryl AUSA Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA McKee Theodore Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Rendell Marjorie Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Restrepo Luis Felipe ACLU National Prison Project; Former Federal Public Defender Circuit 03 Scranton PA Vanaskie Thomas Circuit 04 Raleigh NC Duncan Allyson Circuit 04 Richmond -

Master of Laws

APPLYING FOR & FINANCING YOUR LLM MASTER OF LAWS APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS APPLICATION CHECKLIST Admission to the LLM program is highly For applications to be considered, they must include the following: competitive. To be admitted to the program, ALL APPLICANTS INTERNATIONAL APPLICANTS applicants must possess the following: • Application & Application Fee – apply • Applicants with Foreign Credentials - For electronically via LLM.LSAC.ORG, and pay applicants whose native language is not • A Juris Doctor (JD) degree from an ABA-accredited non-refundable application fee of $75 English and who do not posses a degree from law school or an equivalent degree (a Bachelor of Laws • Official Transcripts: all undergraduate and a college or university whose primary language or LL.B.) from a law school outside the United States. graduate level degrees of instruction is English, current TOEFL or IELTS • Official Law School or Equivalent Transcripts scores showing sufficient proficiency in the • For non-lawyers interested in the LLM in Intellectual • For non-lawyer IP professionals: proof of English language is required. The George Mason Property (IP) Law: a Bachelor’s degree and a Master’s minimum of four years professional experience University Scalia Law School Institution code degree in another field, accompanied by a minimum in an IP-related field is 5827. of four years work experience in IP may be accepted in • 500-Word Statement of Purpose • TOEFL: Minimum of 90 in the iBT test lieu of a law degree. IP trainees and Patent Examiners • Resume (100 or above highly preferred) OR (including Bengoshi) with four or more years of • Letters of Recommendation (2 required) • IELTS: Minimum of 6.5 (7.5 or above experience in IP are welcome to apply. -

The Place of Skills in Legal Education*

THE PLACE OF SKILLS IN LEGAL EDUCATION* 1. SCOPE AND PURPOSE OF THE REPORT. There is as yet little in the way of war or post-war "permanent" change in curriculum which is sufficiently advanced to warrant a sur- vey of actual developments. Yet it may well be that the simpler curricu- lum which has been an effect of reduced staff will not be without its post-war effects. We believe that work with the simpler curriculum has made rather persuasive two conclusions: first, that the basic values we have been seeking by case-law instruction are produced about as well from a smaller body of case-courses as from a larger body of them; and second, that even when classes are small and instruction insofar more individual, we still find difficulty in getting those basic values across, throughout the class, in terms of a resulting reliable and minimum pro- fessional competence. We urge serious attention to the widespread dis- satisfaction which law teachers, individually and at large, have been ex- periencing and expressing in regard to their classes during these war years. We do not believe that this dissatisfaction is adequately ac- counted for by any distraction of students' interest. We believe that it rests on the fact that we have been teaching classes which contain fewer "top" students. We do not believe that the "C" students are either getting materially less instruction-value or turning in materially poorer papers than in pre-war days. What we do believe is that until recently the gratifying performance of our best has floated like a curtain between our eyes and the unpleasant realization of what our "lower half" has not been getting from instruction. -

Medical News

903 Medical News. ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS OF ENGLAND.—— At the meeting of the Council of this College on March 12the diplomas of M.R.C.S. were conferred upon the following two gentlemen who have passed the final examination of the Examining Board in England in Medicine, Surgery, and Midwifery and have complied with the by-laws :- Bertram Arthur Lloyd, Birmingham University ; and David Ranken. M.B., B.S. Lond., M.B., B.S. Durh., Durham University. UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE.-The following. degrees were conferred on March 7th :- M.D.—H. Beckton, Clare; and R. D. Smedley, Pembroke. M.B., B.C.-P. J. Verrall. Trinity. M.B.-S. P. Charr, Gonville and Caius ; The following were conferred on March 12the :- M.D.-H. Robinson and J. E. Spicer, Trinity; and A. E. Taylor,. Downing. 31.B., B.C.-P. H. Bahr, Trinity. M.B.-D. W. A. Bull, Gonville and Caius. B.C.-G. B. Fleming, King’s; G. Graham and C. W. Hutt, Trinity; T. C. Lucas, Clare; and H. H. Taylor, Pembroke. Mr. R. H. Biffen, M.A., of Emmanuel College, has been elected Professor of Agricultural Botany. Mr. C. L. Boulenger, B.A., King’s College, has been appointed assistant to the Superintendent of the Museum of Zoology. TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN.-At the Final Examination in Medicine in Hilary term the following candi- dates were successful :- PART II. (Surgery).-William S. Thacker, John L. Phibbs, Thomas P. Dowley, and Alfred H. Smith. FOREIGN UNIVERSITY INTELLIGENCE.- Amsterdam : Dr. M. Van Londen has been recognised as privat-docent of Neurology.-Baltimore (University of Mary- land): Dr. -

Knowing and Expressing Ourselves

KNOWING AND EXPRESSING OURSELVES BENJAMIN WINOKUR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN PHILOSOPHY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO FEBRUARY 2021 ©BENJAMIN WINOKUR, 2021 Abstract This dissertation concerns two epistemologically puzzling phenomena. The first phenomenon is the authority that each of us has over our minds. Roughly, to have authority is to be owed (and to tend to receive) a special sort of deference when self-ascribing your current mental states. The second phenomenon is our privileged and peculiar self-knowledge. Roughly, self-knowledge is privileged insofar as one knows one’s mental states in a way that is highly epistemically secure relative to other varieties of contingent empirical knowledge. Roughly, one has peculiar self- knowledge insofar as one acquires it in a way that is available only to oneself. In Chapter One I consider several more detailed specifications of our self-ascriptive authority. Some specifications emphasize the relative indubitability of our self-ascriptions, while others focus on their presumptive truth. In Chapter Two I defend a “Neo-Expressivist” explanation of authority. According to Neo- Expressivism, self-ascriptions are authoritative insofar as they are acts that put one’s mental states on display for others, whether or not these mental states are also known by the self- ascriber with privilege and peculiarity. However, I do not dispute that we often have privileged and peculiar self-knowledge. This raises the question of what such knowledge does explain, if not the authority of our self-ascriptions. -

New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth

UC Irvine Law Review Volume 6 Article 3 Issue 2 The New Legal Realism at Ten Years 6-2016 Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth Elizabeth Mertz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Bryant Garth & Elizabeth Mertz, Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond, 6 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 121 (2016). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol6/iss2/3 This Foreword is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Law Review by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. Garth & Mertz UPDATED 4.14.17 (Do Not Delete) 4/19/2017 9:40 AM Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth* and Elizabeth Mertz** I. Celebrating Ten Years of New Legal Realism ........................................................ 121 II. A Developing Tradition ............................................................................................ 124 III. Current Realist Directions: The Symposium Articles ....................................... 131 Conclusion: Moving Forward ....................................................................................... 134 I. CELEBRATING TEN YEARS OF NEW LEGAL REALISM This symposium commemorates the tenth year that a body of research has formally flown under the banner of New Legal Realism (NLR).1 We are very pleased * Chancellor’s Professor of Law, University of California, Irvine School of Law; American Bar Foundation, Director Emeritus. ** Research Faculty, American Bar Foundation; John and Rylla Bosshard Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. Many thanks are owed to Frances Tung for her help in overseeing part of the original Tenth Anniversary NLR conference, as well as in putting together some aspects of this Symposium. -

Jack Weinstein

DePaul Law Review Volume 64 Issue 2 Winter 2015: Twentieth Annual Clifford Symposium on Tort Law and Social Policy - In Article 4 Honor of Jack Weinstein Jack Weinstein: Judicial Strategist Jeffrey B. Morris Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Jeffrey B. Morris, Jack Weinstein: Judicial Strategist, 64 DePaul L. Rev. (2015) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol64/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JACK WEINSTEIN: JUDICIAL STRATEGIST Jeffrey B. Morris* Fifty years ago, one of the great students of the judicial process, Walter F. Murphy,1 heir to Princeton University’s great tradition of such scholars,2 employed the papers of United States Supreme Court Justices to consider how any one of their number might go about ex- erting influence within and outside the Court. How, Murphy asked, could a justice most efficiently use her resources—official and per- sonal—to achieve a set of policy objectives?3 Murphy argued that there were strategic and tactical courses open for justices to increase their policy influence,4 and that a policy-oriented justice must be pre- pared to consider the relative costs and benefits that might result from her formal decisions and informal efforts at influence.5 There were, Murphy argued, a wide variety -

Distinguishing Science from Philosophy: a Critical Assessment of Thomas Nagel's Recommendation for Public Education Melissa Lammey

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Distinguishing Science from Philosophy: A Critical Assessment of Thomas Nagel's Recommendation for Public Education Melissa Lammey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES DISTINGUISHING SCIENCE FROM PHILOSOPHY: A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF THOMAS NAGEL’S RECOMMENDATION FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION By MELISSA LAMMEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Melissa Lammey defended this dissertation on February 10, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Ruse Professor Directing Dissertation Sherry Southerland University Representative Justin Leiber Committee Member Piers Rawling Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Warren & Irene Wilson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the contributions of Michael Ruse to my academic development. Without his direction, this dissertation would not have been possible and I am indebted to him for his patience, persistence, and guidance. I would also like to acknowledge the efforts of Sherry Southerland in helping me to learn more about science and science education and for her guidance throughout this project. In addition, I am grateful to Piers Rawling and Justin Leiber for their service on my committee. I would like to thank Stephen Konscol for his vital and continuing support. -

The Law of Mental Illness

DEVELOPMENTS IN THE LAW THE LAW OF MENTAL ILLNESS “[D]oing time in prison is particularly difficult for prisoners with men- tal illness that impairs their thinking, emotional responses, and ability to cope. They have unique needs for special programs, facilities, and extensive and varied health services. Compared to other prisoners, moreover, prisoners with mental illness also are more likely to be ex- ploited and victimized by other inmates.” HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, ILL-EQUIPPED: U.S. PRISONS AND OFFENDERS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS 2 (2003), available at http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/usa1003/usa1003.pdf. “[I]ndividuals with disabilities are a discrete and insular minority who have been faced with restrictions and limitations, subjected to a history of purposeful unequal treatment, and relegated to a position of political powerlessness in our society, based on characteristics that are beyond the control of such individuals and resulting from stereotypic assumptions not truly indicative of the individual ability of such indi- viduals to participate in, and contribute to, society . .” Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-336, § 2(a)(7), 104 Stat. 327, 329 (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 12101 (2000)). “We as a Nation have long neglected the mentally ill . .” Remarks [of President John F. Kennedy] on Proposed Measures To Combat Mental Illness and Mental Retardation, PUB. PAPERS 137, 138 (Feb. 5, 1963). “[H]umans are composed of more than flesh and bone . [M]ental health, just as much as physical health, is a mainstay of life.” Madrid v. Gomez, 889 F. Supp. 1146, 1261 (N.D. Cal. -

Banner of Light V30 N13 9 Dec 1871

fWM. WHITE & UO.,1 (*3,00 PER ANNUM,! VOL. XXX. iPobliihsrs and Pr.prlaton. J BOSTON, SATURDAY, DECEMBER 9, 1871 I In Adriaca. J NO. 13 sees of old, rather than thankfully receive, in the Writ.” When our unwelcome visitors went, h6w- occur; for, to the vision of the denirun» of that diums made quite sick through an abrupt exer Spirholism. spirit of the little child, as a free gift. Whilst in ever, they took with them from bur medium tbe world of cause», the thoughts of the soul, whether tion of a malign will-power from soma one or this state of mind I seldom received much that <elements necessary for spirit communication, so in earth or spirit-life, are trai »parent. For this more in the circle, very much an I once saw Read Written for the Banner of Light. was satisfactory. Finally, through what I learn- Ithat in that and thret subsequent occasions we reason, probably, we eeldom, If ever, find an un affected by the iibrnpt introduction of light, at had to give up our siiWrtgs.. clothed aoul that will not respond to the proffers one of his circles held In Washington »treat, Bos mediums and mediumship. ed from multitudes of mediumistic experiences, and the forbearance and kindly reproofs and On the next occfsikltf^ir similar annoyance, I of love and sympathy, when made in sincerity of ton, Home years ago, at which ho was, as usual, UY THOMAS B. HAZARD. teachings of my spirit-friends that I wassode- ventured to try the strength of exorcism in a heart. -

P Phd in Pharma Aceutic Cal Scie Ences

PhD in Pharmaceutical Sciences Last modified July 13, 2010 The current Ph.D. in Pharmaceutical Sciences with specialization in Pharmacy graduate program is offered by the Department of Pharmaceutics. The departmental faculty has decided to use 'track' method for accommodating the diversityy of the Department's graduate population, its multi- and interdisciplinary. The focus of the Department of Pharmaceutics, whiich houses the Center for Drug Discovery, differs sufficiently from that of other departments as to justify a specialization. The uniqueness of the department is evident in present reesearch activities which encompass basic, applied and clinical investigations in the areas of Biopharmaceutics and Pharmacokinetics, Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Pharmaceutical Analysis, Drug Delivery, and Drug Discovery. Specifically, Biopharmaceutics and Pharmacokinetics, encompasses the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of drugs in animals and humans, and the relationship between drug concentration and effect; Pharmaceuutical Biotechnology includes molecular biology, immunology, and aspects of the delivery off peptide and protein drugs; Pharmaceutical Analysis involves the application of spectroscopy, chromatography, extraction, electrophoresis, immunoassays, and radioisotope assays to drug determination; Drug Delivery includes physical, biological and chemical approaches to drug delivery, formulation and evaluation of dosage forms; and Drug Discovery is associated with receptor-oriented/retrometabolic drug design, computer assisted drug design, chemical/physical approaches to controlled drug delivery, pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic correlation approach to improved therapeutic index. 1 Objectives of the Ph.D. Program Faculty Adjunct Faculty Governance Recruitment of Students Admission Procedures Financial Assistance Selection of Discipline for Degree and Major Professor Supervisory Committee Curriculum Qualifying Examination Final Examination Specific Requirements for the Master of Science in Pharmacy Degree The objectives of the Ph.D.