5 Books from Croatia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questioning Identity, Humanity and Culture Through Japanese Anime

The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan The Many Faces of Popular Culture and Contemporary Processes: Questioning Identity, Humanity and Culture through Japanese Anime Mateja Kovacic Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong 0434 The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract In a highly globalized world we live in, popular culture bears a very distinctive role: it becomes a global medium for borderless questioning of ourselves and our identities as well as our humanity in an ever-transforming environment which requires us to be constantly ''plugged in'' in order to respond to all the challenges as best as we can. Vast cultural products we create and consume every day thus provide a relevant insight into problems that both researchers and audiences have to face with in an informatised and technologised world. Japanese anime is one of such cultural products: a locally produced cultural artifact became a global phenomenon that transcends cultures and spaces. In its imageries we discover a wide range of themes that concern us today, ranging from bioethical issues, such as ecological crisis, posthumanism and loss of identity in a highly transforming world to the issues of traditionality and spirituality. The author will show in what ways we can approach and study popular culture products in order to understand the anxieties and prevailing concerns of our cultures today, with emphasis on the identity and humanity, and their position in the contemporary high-tech world we live in. The author's intention is to point to popular culture as a significant (re)source for the fields of humanities and cultural studies, as well as for discussing human transformations and possible future outcomes of these transformations in a technoscientific world. -

1: for Me, It Was Personal Names with Too Many of the Letter "Q"

1: For me, it was personal names with too many of the letter "q", "z", or "x". With apostrophes. Big indicator of "call a rabbit a smeerp"; and generally, a given name turns up on page 1... 2: Large scale conspiracies over large time scales that remain secret and don't fall apart. (This is not *explicitly* limited to SF, but appears more often in branded-cyberpunk than one would hope for a subgenre borne out of Bruce Sterling being politically realistic in a zine.) Pretty much *any* form of large-scale space travel. Low earth orbit, not so much; but, human beings in tin cans going to other planets within the solar system is an expensive multi-year endevour that is unlikely to be done on a more regular basis than people went back and forth between Europe and the americas prior to steam ships. Forget about interstellar travel. Any variation on the old chestnut of "robots/ais can't be emotional/creative". On the one hand, this is realistic because human beings have a tendency for othering other races with beliefs and assumptions that don't hold up to any kind of scrutiny (see, for instance, the relatively common belief in pre-1850 US that black people literally couldn't feel pain). On the other hand, we're nowhere near AGI right now and it's already obvious to everyone with even limited experience that AI can be creative (nothing is more creative than a PRNG) and emotional (since emotions are the least complex and most mechanical part of human experience and thus are easy to simulate). -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6638/pennsylvania-county-histories-186638.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

HEFEI IENCE ^SVM^y fji 7%r COLLEIjTIONS y. ^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun89unse A Page4 ' . s- p Page S . ; Page1 ■ | - - ' r u v w . _ ... Ml*. v w- XYZ .-Ml j|f • • MV-j | gaveno intimation of a desire to be in~ terviewed or remonstrated with, which 0:j ^lcrricli. motive they even had the bad taste to resent in a very unpleasant manner, did not improve as he had hoped, the writer’s health. So it come to pass that a short Oil- CITY CHROSICrafBS. time after the battle of Wilson’s Creek, he found himself at Cincinnati on board A Brief Compilation,* Incidental and of a river steamer bound for Pittsburg. Otherwise, From 1861 to Bate. At Maysviile a gentleman came on the r Written for the Derrick.] steamer who was en route for the Oil N this and the series of articles Country, where he had been engaged in to follow,the writer proposes to the development. He was a fluent talk¬ relate from the memory of him¬ er, and from him was gleaned the first self and others, such incidents general information in relation to the of the early history of Oil City, new discovery. Yet the revelation he as can be had and may be made was so wild and apparently impos¬ deemed of interest. -

Introduction When the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – from 1929 Kingdom of Yugoslavia – Was Formed in 1918, One of I

Introduction When the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – from 1929 Kingdom of Yugoslavia – was formed in 1918, one of its most important tasks was to forge a common collective identity. Intellectual elites in the young state with great optimism agreed that education would play a crucial role in this process. It should come as no surprise, then, that a relatively rich tradition of scholarly research into the representation of collective identities in Yugoslav education has originated, precisely to account for the failure of the Yugoslav project in the long term. Recently, a growing body of scholarly research has established textbooks as one of the more rewarding sources for studying collective identity in education, focusing on ‘what knowledge is included and rejected in ... textbooks, and how the transmission of this selected knowledge often attempts to shape a particular form of national memory, national identity and national consciousness’.1 For the Yugoslav case this emerging research field so far has primarily examined textbooks which were used in the period directly preceding, during and following the disintegration of Yugoslavia.2 However, as the present article hopes to illustrate, textbook analysis can also provide the historian with interesting new elements for the study of collective identities in Yugoslavia’s more distant past. With its focus on national identity in Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian textbooks before the First World War, and later also in interwar Yugoslavia, the work of Charles Jelavich still occupies a somewhat -

The Post-Yugoslav Space Politics and Economics

TRANSITIONS 3LZ]VS\TLZ0n???000VU[t[tW\ISPtZZV\ZSLUVT̷9L]\LKLZ7H`ZKLS»,Z[̷® The Post-Yugoslav Space Politics and Economics edited by Barbara DELCOURT & Klaus-Gerd GIESEN =VS © IS/IEUG Juin 2013 avenue Jeanne, 44, CP 124 - 1050 BRUXELLES Tel. 32.2/650.34.42 e.mail : [email protected] – http://www.ulb.ac.be/is/revtrans.html ISSN n° 0779-3812 ISBN 2-87263-041-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Barbara Delcourt & Klaus-Gerd Giesen 5 Yugoslavia in Western Nation-Building Strategy – A Historical Perspective Kees van der Pijl 11 State Borders, Symbolic Boundaries and Contested Geographical Space: Citizenship Struggles in Kosovo Gëzim Krasniqi 29 Linguistic Politics in Ex-Yugoslavia: The Case of Purism in Croatia Tea Pršir 53 Economic Wheels of Transition: Yugoslav Space 20 Years on 0LURVODYD)LOLSRYLü 71 Post-Yugoslav Sovereignties, Rentier Capitalism, and The European Economic Crisis Klaus-Gerd Giesen 101 ‘Truth And Reconciliation’: A New Political Subjectivity for Post-Yugoslavs? 6ORERGDQ.DUDPDQLü 117 LINGUISTIC POLITICS IN EX!YUGOSLAVIA: THE CASE OF PURISM IN CROATIA Tea PRŠIR 1. INTRODUCTION /LQJXLVWLFSXUL¿FDWLRQKDVH[LVWHGLQ&URDWLDEHIRUHLWVSROLWLFDOLQGHSHQGHQFH in 1991, as will be discussed in §2. In the 19th FHQWXU\ SXUL¿FDWLRQ ZDV IRFXVHG against non-Slavic languages such as German, Hungarian, Latin and Italian. After the Yugoslav wars it focused against “Serbianisms”. By this term, Croatian purists designate the words that entered the Croatian language during the years of common state history with the Serbian people. Serbianisms were the main preoccupation for some Croatian linguists from 1990 until 2000. They proposed (and sometimes even imposed) discarding these and replacing them with neologisms. -

The Book Art in Croatia Exhibition Catalogue

Book Art in Croatia BOOK ART IN CROATIA National and University Library in Zagreb, Zagreb, 2018 Contents Foreword / 4 Centuries of Book Art in Croatia / 5 Catalogue / 21 Foreword The National and University Library in Croatia, with the aim to present and promote the Croatian cultural heritage has prepared the exhibition Book Art in Croatia. The exhibition gives a historical view of book preparation and design in Croatia from the Middle Ages to the present day. It includes manuscript and printed books on different topics and themes, from mediaeval evangelistaries and missals to contemporary illustrated editions, print portfolios and artists’ books. Featured are the items that represent the best samples of artistic book design in Croatia with regard to their graphic design and harmonious relationship between the visual and graphic layout and content. The author of the exhibition is art historian Milan Pelc, who selected 60 items for presentation on panels. In addition to the introductory essay, the publication contains the catalogue of items with short descriptions. 4 Milan Pelc CENTURIES OF BOOK ART IN CROATIA Introduction Book art, a constituent part of written culture and Croatian cultural heritage as a whole, is ex- ceptionally rich and diverse. This essay does not pretend to describe it in its entirety. Its goal is to shed light on some (key) moments in its complex historical development and point to its most important specificities. The essay does not pertain to entire Croatian literary heritage, but only to the part created on the historical Croatian territory and created by the Croats. Namely, with regard to its origins, the Croatian literary heritage can be divided into three big groups. -

Death and Dying in the Works of Two Croatian Writers

Death and Dying in the Works of Two Croatian Writers Iva Rineid-Lerga, M.A.pol. Amir Muzur, M.D., Ph.D. Rijeka University School of Medicine, Rijeka, Croatia ABSTRACT: The present paper elucidates the views upon death and dying expressed in the works of two Croatian writers, Dobrisa Cesarid and Miroslav Krleza. Both authors' concepts are materialistic, Cesari6's being more romantic and Krleza's more expressively cruel. Neither of the two mentions any religious element or fear. The paper concludes with a suggestion of an inquiry into the influence of the works by Cesaric and Krleza upon the ideas of modern elementary school and high school generations on death and dying. KEY WORDS: death; dying; bioethics; medicine and literature; Croatia. Despite the aggressive advancement of other communication media more appropriate to modern life style and tempo, literature has remained an important factor in human education. It is not usual to intermingle literature, and particularly fiction, with scientifically explored topics. However, in those rare areas where science still cannot offer any answer, as in thanatology, we must search for such answers and compile them from alternative sources, such as religion, philosophy, and literature. We believe that, when it comes to death and dying, literature can provide very interesting although sometimes opposing views that Iva Rincic-Lerga, M.A.pol., is in the Department of Social Sciences, Rijeka University School of Medicine, Rijeka, Croatia, where Amir Muzur, M.D., Ph.D., is with the Department of Family Medicine. Reprint requests should be addressed to Mr. sc. Iva Rincic-Lerga, Katedra za Drustvene Znanosti, Medicinski Fakultet Sveucilista u Rijeci, Brace Branchetta 20, 51 000 Rijeka, Croatia; e-mail: [email protected]. -

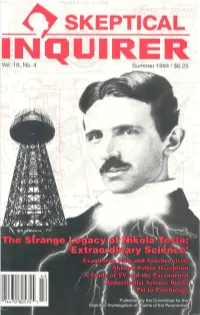

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

The Croatian Ustasha Regime and Its Policies Towards

THE IDEOLOGY OF NATION AND RACE: THE CROATIAN USTASHA REGIME AND ITS POLICIES TOWARD MINORITIES IN THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF CROATIA, 1941-1945. NEVENKO BARTULIN A thesis submitted in fulfilment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales November 2006 1 2 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Nicholas Doumanis, lecturer in the School of History at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia, for the valuable guidance, advice and suggestions that he has provided me in the course of the writing of this thesis. Thanks also go to his colleague, and my co-supervisor, Günther Minnerup, as well as to Dr. Milan Vojkovi, who also read this thesis. I further owe a great deal of gratitude to the rest of the academic and administrative staff of the School of History at UNSW, and especially to my fellow research students, in particular, Matthew Fitzpatrick, Susie Protschky and Sally Cove, for all their help, support and companionship. Thanks are also due to the staff of the Department of History at the University of Zagreb (Sveuilište u Zagrebu), particularly prof. dr. sc. Ivo Goldstein, and to the staff of the Croatian State Archive (Hrvatski državni arhiv) and the National and University Library (Nacionalna i sveuilišna knjižnica) in Zagreb, for the assistance they provided me during my research trip to Croatia in 2004. I must also thank the University of Zagreb’s Office for International Relations (Ured za meunarodnu suradnju) for the accommodation made available to me during my research trip. -

Slovothek Nr.1

Impressum: SlovoKult, Slovothek Nr. 1, Berlin-Skopje, 2010 © (wenn nicht anders vermerkt) alle Rechte bei den Autoren und den Übersetzern, Berlin-Skopje, 2010. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Kein Teil dieser Publika on darf ohne vorherige Zus mmung durch den Herausgeber in irgendeiner Form oder auf irgendeine Weise - sei es elektronisch, mechanisch, als Fotokopie, Aufnahme oder anderwei g - reproduziert, auf einem Daten- träger gespeichert oder übertragen werden. ISBN 978-9989-59-323-9 Die Veröff entlichung dieser Publika on wurde von dem Verein Albanischer Verleger in Makedonien (Associa on of Albanian Publishers - AAP - in Macedonia) ermöglicht. Diese Publika on wurde zum Teil von dem Kultusministerium der Republik Makedonien unterstützt. Herausgeber: SlovoKult (Elizabeta Lindner) Verlag: Blesok, Skopje Umschlaggestaltung: Ana Matovska Umschlagfoto: Elizabeta Lindner Layout und Satz: Igor Isakovski Lektorat: Petra Huber und Benjamin Langer Druck: Maring, Skopje, 2010 Printed in Macedonia Aufl age: 700 Kontakt: SlovoKult: www.slovokult.de; [email protected] Blesok: www.blesok.com.mk; [email protected] AAP: www.libri.org.mk; [email protected] SlovoKult.de Slovothek Nr. 1 Lyrik von: Kata Kulavkova, Igor Isakovski, Eftim Kletnikov und Vladimir Martinovski Prosa von: Igor Isakovski, Luan Starova, Dragi Mihajlovski, Kim Mehmeti, Goce Smilevski, Petre M. Andreevski und Aleksandar Prokopiev SlovoKult (www.slovokult.de) ist ein Online-Literaturportal für make- donische Literatur auf Deutsch. Es wurde 2008 von Elizabeta Lindner gegründet und hat sich mi lerweile zu einem Übersetzernetzwerk entwickelt, das regelmäßig übersetzte Literatur aus Makedonien ver- öff entlicht. SlovoKult sind: Elizabeta Lindner, Petra Huber, Benjamin Langer, Will Firth, Ksenija Čočkova und Lydia Nagel. Für diese erste Ausgabe der Textsammlung Slovothek Nr. -

ZAGORAA Cultural/Historical Guide to the Zagora (Inland) Region of Split

A cultural/historical guide to the Zagora (inland) region of Split-Dalmatia County ZAGORA THE DALMATIAN ZAGORA (INLAND) Joško Belamarić THE DALMATIAN ZAGORA (INLAND) A cultural/historical guide to the Zagora (inland) region of Split-Dalmatia County 4 Zagora 14 Klis Zagora 24 Cetinska krajina 58 Biokovo, Imotski, Vrgorac 3 Zagora THE DALMATIAN ZAGORA (INLAND) A cultural/historical guide to the Zagora (inland) region of Split-Dalmatia County Here, from Klis onwards, on the ridge of the Dinara mountain chain, the angst of inland Dalmatia’s course wastelands has for centuries been sundered from the broad seas that lead to a wider world. The experience of saying one’s goodbyes to the thin line of Dalmatia that has strung itself under the mountain’s crest, that viewed from the sea looks like Atlas’ brothers, is repeated, not without poetic chills, by dozens of travel writers. To define the cultural denominators of Zagora, the Dalmatian inland, is today a difficult task, as the anthropological fabric of the wider Dalmatian hinterland is still too often perceived through the utopian aspect of the Renaissance ideal, the cynicism of the Enlightenment, or the exaggeration of Romanticism and the 18th century national revival. After the fall of medieval feudalism, life here has started from scratch so many times - later observers have the impression that the local customs draw their roots from some untroubled prehistoric source in which the silence of the karst on the plateau towards Promina, behind Biokovo, the gurgling of the living waters of the Zrmanja, Krka, Čikola and Cetina Ri- vers, the quivering of grain on Petrovo, Hrvatac and Vrgorac Fields, on 4 Zagora the fat lands along Strmica and Sinj, create the ide- al framework for the pleasant countenance, joyous heart and sincere morality of the local population of which many have written, each from their own point of view: from abbot Fortis and Ivan Lovrić during the Baroque period, Dinko Šimunović and Ivan Raos not so long ago to Ivan Aralica and, in his own way, Miljenko Jergović today. -

Istria's Shifting Shoals by Chandler Rosenberser Peter B

NOT FOR PUBLICATION CRR (19) WITHOUT WRITI::WS CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS Istria's shifting shoals by Chandler RosenberSer Peter B. Martin c/o ICWA 4 West Wheelock St. Hanover, N.H. 03755 USA Dear Peter, Pula, CROATIA Navigating along a sandy coast is a tricky business. Winter storms move shoals from one year to the next and maps of the sea's floor quickly go out-of-date. So last September, when rented a boat with some friends and set out down along Slovenia's shore, I was relieved to find we were skirting a rocky rim. After years of crossing disputed borders, I could finally stop worrying whether my map was right. The land of the Istrian peninsula is so firm that medieval Venetian churches still stand secure just a few feet from the water's edge. Their square bell towers are better landmarks than harbor bouys. Leaving Koper and sailing east, all you have to do is count them, as you might bus stops on a familiar route. But the towers are also a testament to the strength of the lost Venetian Republic that built them. Only a great trading power could have kept routes open long enough to allow their slow rise from the shore, CHANDLER ROSENBERGER is a John 0. Crane Memorial Fellow of the Institute writing about the new nations of Central Europe, Since 1925 the Institute of Current World Affairs (the Crane-Rogers Foundation) has provided long-term fellowships to enable outstanding young adults to live outside the United States and write about international areas and issues.