Genre Reflexivity in Post-Millennial Metafictional Horror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 12-1-2019 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century Beverley Rilett University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Rilett, Beverley, "British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century" (2019). Zea E-Books. 81. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. CHARLOTTE SMITH WILLIAM BLAKE WILLIAM WORDSWORTH SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE GEORGE GORDON BYRON PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY JOHN KEATS ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING ALFRED TENNYSON ROBERT BROWNING EMILY BRONTË GEORGE ELIOT MATTHEW ARNOLD GEORGE MEREDITH DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI CHRISTINA ROSSETTI OSCAR WILDE MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE ZEA BOOKS LINCOLN, NEBRASKA ISBN 978-1-60962-163-6 DOI 10.32873/UNL.DC.ZEA.1096 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. University of Nebraska —Lincoln Zea Books Lincoln, Nebraska Collection, notes, preface, and biographical sketches copyright © 2017 by Beverly Park Rilett. All poetry and images reproduced in this volume are in the public domain. ISBN: 978-1-60962-163-6 doi 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1096 Cover image: The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse, 1888 Zea Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries. -

SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 , |FL1 SECTION SECTION SECTION SECTION Table of TABLE OF

11 th ANNUAL SECTION SECTION CONTENT sunscreenCONTENT FILM FESTIVAL Presented by 2016 PROGRAM GUIDE SOUTH BAY - LOS ANGELES April 28 - May 1 ST. PETERSBURGSUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 , |FL1 SECTION SECTION SECTION SECTION Table of OF TABLE WHEN ALL OF YOU GET CONTENTS CONTENT BIG AND FAMOUS AND CONTENTS Welcome 4 CONTENT Box Office Information 5 Box Offices GO TO HOLLYWOOD Tickets & Passes Special Events Workshops PARTIES AND DRIVE Awards Ceremony & After Party AD Festival Schedule 6 - 7 Workshops & Panels 8 - 10 FLASHY CARS, Special Events Schedule 12 Opening Night Gala 13 Celebrity Guests 14 JUSTPAGE REMEMBER, Special Guests 15 - 20 Film Info and Schedule 22 - 48 Thursday • April 28 23 • 24 YOU’LL GET MORE FOR Friday • April 29 25 • 31 Saturday • April 30 32 • 40 YOUR MOVIE HERE. Sundauy • May 1 41 • 47 Sponsors 49 - 51 Get more for your movie here. PROUD SPONSOR OF THE SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2 SUNSCREEN FILM FESTIVAL 2016 | 3 Sunscreen Film Festival ad 5x8.indd 1 4/7/2016 4:24:18 PM BOX OFFICE INFORMATION BOX OFFICE Regular Box Office opens Thursday, April 28 at the primary venue: American Stage, 163 3rd Street, North., St. Petersburg, Florida 33701. WELCOME BOX OFFICES INFORMATION Online Book tickets anytime day or night! Visit our website: www.SunscreenFilmFestival.com Festival Office American Stage. 163 3rd Street, North., St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 SOUTH BAY - LOS ANGELES Telephone Call (727) 259-8417 • Hours: 9:00 am - 5:00 pm • Monday - Sunday Visa and Mastercard, AMEX, Discover accepted at box office (at door) and Paypal accepted for advanced, online tickets and pass purchases. -

Northeastern Loggers Handrook

./ NORTHEASTERN LOGGERS HANDROOK U. S. Deportment of Agricnitnre Hondbook No. 6 r L ii- ^ y ,^--i==â crk ■^ --> v-'/C'^ ¿'x'&So, Âfy % zr. j*' i-.nif.*- -^«L- V^ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AGRICULTURE HANDBOOK NO. 6 JANUARY 1951 NORTHEASTERN LOGGERS' HANDBOOK by FRED C. SIMMONS, logging specialist NORTHEASTERN FOREST EXPERIMENT STATION FOREST SERVICE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE - - - WASHINGTON, D. C, 1951 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 75 cents Preface THOSE who want to be successful in any line of work or business must learn the tricks of the trade one way or another. For most occupations there is a wealth of published information that explains how the job can best be done without taking too many knocks in the hard school of experience. For logging, however, there has been no ade- quate source of information that could be understood and used by the man who actually does the work in the woods. This NORTHEASTERN LOGGERS' HANDBOOK brings to- gether what the young or inexperienced woodsman needs to know about the care and use of logging tools and about the best of the old and new devices and techniques for logging under the conditions existing in the northeastern part of the United States. Emphasis has been given to the matter of workers' safety because the accident rate in logging is much higher than it should be. Sections of the handbook have previously been circulated in a pre- liminary edition. Scores of suggestions have been made to the author by logging operators, equipment manufacturers, and professional forest- ers. -

2016 Film Writings by Roderick Heath @ Ferdy on Films

2016 Film Writings by Roderick Heath @ Ferdy On Films © Text by Roderick Heath. All rights reserved. Contents: Page Man in the Wilderness (1971) / The Revenant (2015) 2 Titanic (1997) 12 Blowup (1966) 24 The Big Trail (1930) 36 The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) 49 Dead Presidents (1995) 60 Knight of Cups (2015) 68 Yellow Submarine (1968) 77 Point Blank (1967) 88 Think Fast, Mr. Moto / Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937) 98 Push (2009) 112 Hercules in the Centre of the Earth (Ercole al Centro della Terra, 1961) 122 Airport (1970) / Airport 1975 (1974) / Airport ’77 (1977) / The Concorde… Airport ’79 (1979) 130 High-Rise (2015) 143 Jurassic Park (1993) 153 The Time Machine (1960) 163 Zardoz (1974) 174 The War of the Worlds (1953) 184 A Trip to the Moon (Voyage dans la lune, 1902) 201 2046 (2004) 216 Bride of Frankenstein (1935) 226 Alien (1979) 241 Solaris (Solyaris, 1972) 252 Metropolis (1926) 263 Fährmann Maria (1936) / Strangler of the Swamp (1946) 281 Viy (1967) 296 Night of the Living Dead (1968) 306 Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016) 320 Neruda / Jackie (2016) 328 Rogue One (2016) 339 Man in the Wilderness (1971) / The Revenant (2015) Directors: Richard C. Sarafian / Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu By Roderick Heath The story of Hugh Glass contains the essence of American frontier mythology—the cruelty of nature met with the indomitable grit and resolve of the frontiersman. It‘s the sort of story breathlessly reported in pulp novellas and pseudohistories, and more recently, of course, movies. Glass, born in Pennsylvania in 1780, found his place in legend as a member of a fur-trading expedition led by General William Henry Ashley, setting out in 1822 with a force of about a hundred men, including other figures that would become vital in pioneering annals, like Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith, and John Fitzgerald. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 518 IR 000 359 TITLE Film Catalog of The

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 518 IR 000 359 TITLE Film Catalog of the New York State Library. 1973 Supplement. INSTITUTION New York State Education Dept., Albany. Div. of Library Development. PUB DATE 73 NOTE 228p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$11.40 DESCRIPTORS *Catalogs; Community Organizations; *Film Libraries; *Films; *Library Collections; Public Libraries; *State Libraries; State Programs IDENTIFIERS New York State; New York State Division of Library Development; *New York State Library ABSTRACT Several hundred films contained in the New York State Division of Library Development's collection are listed in this reference work. The majority of these have only become available since the issuance of the 1970 edition of the "Catalog," although a few are older. The collection covers a wide spectrum of subjects and is intended for nonschcol use by local community groups; distribution is accomplished through local public libraries. Both alphabetical and subject listings are provided and each"citation includes information about the film's running time, whether it is in color, its source, and its date. Brief annotations are also given which describe the content of the film and the type of audience for which it is appropriate. A directory of sources is appended. (PB) em. I/ I dal 411 114 i MI1 SUPPLEMENT gilL""-iTiF "Ii" Alm k I I II 11111_M11IN mu CO r-i Le, co co FILM CATALOG ca OF THE '1-1-1 NEW YORK STATE LIBRARY 1973 SUPPLEMENT THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT ALBANY, 1973 THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ( with years when terms expire) 1984 JOSEPH W. -

Combined Film Catalog, 1972, United States Atomic Energy

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 067 273 SE 014 815 TITLE Combined FilmCatalog, 1972, United States Atomic Energy Commission.. INSTITUTION Atomic EnergyCommission, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 73p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Audiovisual Aids; Ecology; *Energy; *Environmental Education; Health Education; Instructional Materials; *Nuclear Physics; *Physical Sciences; Pollution; Radiation ABSTRACT A comprehensive listing of all current United States Atomic Energy Commission( USAEC) films, this catalog describes 232 films in two major film collections. Part One: Education-Information contains 17 subject categories and two series and describes 134 films with indicated understanding levels on each film for use by schools. The categories include such subjects as: Biology and Agriculture, Environment and Ecology, Industrial Applications, Medicine, Peaceful Uses, Power Reactors, and Research. Part Two: Technical-Professional lists 16 subject categories and describes 98 technical films for use primarily by professional audiences such as colleges and universities, industry, researchers, scientists, engineers and technologists. The subjects include: Engineering, Fuels, Medicine, Peaceful Nuclear Explosives, Physical Research, and Principles of Atomic Energy. All films are available from the five USAEC libraries listed. A section on "Advice To Borrowers" and request forms for ordering AEC films follow. (LK) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EOUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIG INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY RF °RESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OFEDU CATION POSITION OR POLICY 16 mm A A I I I University of Alaska Film Library NOTICE Atomic Energy Film Section Division of Public Service With theissuanceof this 1972 catalog, the USAEC 109 Eielson Building announces that allthe domestic film libraries (except College, Alaska 99701 Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico) have been consolidated Phone:907-479-7296 into one new library. -

A-Z Movies August

AUGUST 2021 A-Z MOVIES 1% Mickey Mantle compete against each Of SHARKBOY Sci-Fi/Fantasy (M lv) Based on a true story. An American John Cleese, Amy Irving. MOVIES PREMIERE 2017 other to break Babe Ruth’s single- AND LAVAGIRL August 7, 16 student spending a semester abroad Lured out to the Old West, Fievel the Drama (MA 15+ alsv) season home run record. MOVIES KIDS 2005 Family Sigourney Weaver, Charles S Dutton. in Perugia, Italy, garners international mouse joins forces with a famed dog After being put into an extended sleep attention after she is put on trial sheriff to thwart a sinister plot. August 22 August 6, 15, 25 Matt Nable, Ryan Corr. 100% WOLF Taylor Lautner, Taylor Dooley. state after her last fight with the aliens, for her part in the murder of British The heir to the throne of a notorious MOVIES FAMILY 2020 Family (PG) A boy’s imaginary superhero friends Ellen Ripley crash-lands onto a planet housemate, Meredith Kercher. AN AMISH MURDER outlaw motorcycle club must betray August 9, 18, 31 come to life and join him on a series which is inhabited by the former LIFETIME MOVIES 2013 his president to save his brother’s life. Jai Courtney, Samara Weaving. of adventures. inmates of a maximum-security prison. AMERIcaN DREAMZ Thriller/Suspense (M av) The heir to a family of werewolves MOVIES COMEDY 2006 Comedy (M ls) August 5, 10, 14, 20, 24, 29 12 STRONG experiences his first transformation ALIEN: RESURRECTION August 13, 19 Neve Campbell, Noam Jenkins. MOVIES ACTION 2018 on his 13th birthday, morphing into THE ADVENTURES OF TOM MOVIES GREATS 1997 Hugh Grant, Dennis Quaid. -

Ecocinema and the Indigenous Film Festival Salma Monani Gettysburg College

Environmental Studies Faculty Publications Environmental Studies 2013 ImagineNATIVE 2012: Ecocinema and The Indigenous Film Festival Salma Monani Gettysburg College Miranda Brady Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/esfac Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Salma Monani and Miranda Brady, “ImagineNATIVE 2012: Indigenous Film Festival as Ecocinematic Space” in Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture 13.3-4 (2013, online only). This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/esfac/64 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ImagineNATIVE 2012: Ecocinema and The ndiI genous Film Festival Abstract Much scholarship points to how ecological concerns are never far from Indigenous struggles for political sovereignty and public participation. In this paper we turn to the Indigenous film festival as a relatively understudied yet rich site to explore such ecological concerns. Specifically, we highlight the ImagineNATIVE 2012 film festival based in Toronto, Canada. Keywords Indigenous film festival, film festivals, Toronto Disciplines Ecology and Evolutionary Biology | Environmental Sciences This article is available at The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/esfac/64 Reconstruction Vol. 13, No. 3/4 ImagineNATIVE 2012: Ecocinema and The Indigenous Film Festival / Salma Monani and Miranda Brady Abstract: Much scholarship points to how ecological concerns are never far from Indigenous struggles for political sovereignty and public participation. -

By JIMI BERNATH

BARDO FILMS CINEMA OF THE AFTERLIFE by JIMI BERNATH 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction “Carnival of Souls” : Familiar Nightmares …………………………………………………..………...43 Bardo Blockbusters : “American Beauty” & “The Sixth Sense” ……………….……...…..85 “Jacob’s Ladder” : Search for a Guide ……………………………………………………..………….102 “Enter the Void” : Escape Velocity …………………………………………………………..…………. 49 The Dharma of Lynch: “Mulholland Drive” & “Inland Empire” ……………….……….108 “Vera” : The Underworld ………………………………………………………………………..…...……….106 Escape from Hell : “Diamonds of the Night” …………………………………………….………. 26 “Le Quattro Volte” : Elemental Change ……………………………………………………..…………..7 “Beetlejuice” : Guide as Huckster …………………………………………………………….…………..78 “Defending Your Life” : Purgatory as Shtick …………………………………………….…………90 “Ink” : Remembering Who You Were …………………………………………………………….…….59 “The Bothersome Man” : Not Bad As Purgatories Go …………………………….………….64 “The Lovely Bones” : Avenging Angel …………………………………………………………….….55 Following Robin : “Being Human” & “What Dreams May Come” …………………...22 Following Downey : “Chances Are” & “Hearts and Souls” ………………………………..46 Death at an Early Age : “Donnie Darko” & “Wristcutters a Love Story” ………….94 “Samaritan Girl” : Saint or Sinner ……………………………………………………………………..126 “The Life Before Her Eyes” : Headline Bardo ……………………………………………….…….75 Dia de Muertos : “Macario” “The Book of Life” & “Coco” …………………………..……..9 “Waking Life” : All Our Guides …………………………………………………………………….……...68 Japanese Ghost Stories : “Pitfall” & “Kuroneko” ……………………….…………….………..29 Crossing the Big -

Title Republished Last Mod Date Author Section Visitors Views Engaged Minut % New Vis % New Views Minutes Per Ne Minutes Per R

# Title Republished Last Mod Date Author Section Visitors Views Engaged Minut % New Vis % New Views Minutes Per Ne Minutes Per Ret Days Pub in Peri Visitors Per Day Views Per Day L Shares Tags 1 ‘Making a Murderer': Where Are They Now? (Photos) 2016-01-05 13: Tony Maglio Photos 178,004 3,413,345 346,154 85% 85% 1.9 1.8 113 1,569 30,089 594 steven avery,making a murderer,brendan dassey,netflix 2 45 First Looks at New TV Shows From the 2015-2016 Season 2015-05-07 21: Wrap Staff Photos 114,174 2,414,328 161,889 93% 92% 1.3 1.6 119 959 20,288 7 3 9 ‘Making a Murderer’ Memes That Will Make You Laugh While You Seethe 2016-01-04 16: Reid Nakamura Photos 248,427 2,034,710 171,881 87% 86% 0.7 0.7 114 2,173 17,800 726 making a murderer,netflix 4 Hollywood’s Notable Deaths of 2016 (Photos) 2016-01-11 10: Jeremy Fuster Movies 137,711 1,852,952 158,816 91% 92% 1.1 1 108 1,280 17,227 375 george gaynes,ken howard,joe garagiola,malik taylor,sian blake,frank sinatra jr.,abe vigoda,pat harrington jr.,garry shandling,obituary,craig strickland,vilmos zsigmond,pf 5 Hollywood’s Notable Deaths of 2015 (Photos) 2015-01-08 20: Wrap Staff Movies 27,377 1,112,257 83,702 92% 92% 3 2.9 119 230 9,347 40 lesley gore,hollywood notable deaths,brooke mccarter,uggie,robert loggia,rose siggins,rod taylor,edward herrmann,mary ellen trainor,stuart scott,holly woodlawn,wayn 6 ‘Making a Murderer': 9 Updates in Steven Avery’s Case Since the Premiere (Photos) 2016-01-13 13: Tim Kenneally Crime 134,526 1,093,825 148,880 86% 87% 1.1 1 105 1,276 10,373 224 netflix,laura ricciardi,making -

Lewis Mary C 2018 Masters.Pdf (195.7Kb)

BUTTERFLY JUMP MARY LEWIS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN FILM YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO September 2018 © Mary Lewis, 2018 ABSTRACT Butterfly Jump tells the story of a scrappy woman from the wrong side of the tracks who is a single parent determined to have her children fit into the upper crust. When her children are wrongfully removed from her care due to assumptions rooted more in class prejudices than fact, she must fight the system to get them back. In doing so, she undergoes a radical personal transformation. I am looking at lower-class life and its intersection or clash with the upper crust; Connie Noseworthy is our protagonist whose story carries the heart of the film. Connie’s actions may be viewed as unconscionable and simultaneously understandable. Firmly rooted in a sense of place, its tone is realistic, gritty, suspenseful and intermittently funny. I hope to move the audience to tears of heartbreak as well as joy and laughter and in a story that ultimately bolsters humanity. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’d like to acknowledge my brave friend Jane Walsh who generously shared her story with me and entrusted me to tell it. I acknowledge my trusted supervisor Howie Wiseman whose guidance, wisdom, knowledge, patience and most importantly, kind-hearted encouragement helped me at every turn. Thanks also to my reader at the first draft stage, Amnon Buchbinder who was prompt, thorough and thoughtful with his expert analysis. Kuowei Lee, John Greyson, and Seth Feldman – I am grateful to each of you for your help, guidance and kind encouragement during my tenure at York. -

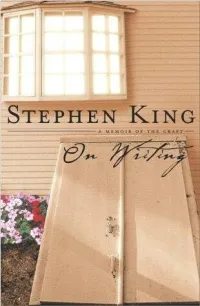

On Writing : a Memoir of the Craft / by Stephen King

l l SCRIBNER 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Visit us on the World Wide Web http://www.SimonSays.com Copyright © 2000 by Stephen King All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work. DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING Set in Garamond No. 3 Library of Congress Publication data is available King, Stephen, 1947– On writing : a memoir of the craft / by Stephen King. p. cm. 1. King, Stephen, 1947– 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. 3. King, Stephen, 1947—Authorship. 4. Horror tales—Authorship. 5. Authorship. I. Title. PS3561.I483 Z475 2000 813'.54—dc21 00-030105 [B] ISBN 0-7432-1153-7 Author’s Note Unless otherwise attributed, all prose examples, both good and evil, were composed by the author. Permissions There Is a Mountain words and music by Donovan Leitch. Copyright © 1967 by Donovan (Music) Ltd. Administered by Peer International Corporation. Copyright renewed. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Granpa Was a Carpenter by John Prine © Walden Music, Inc. (ASCAP). All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publications U.S. Inc., Miami, FL 33014. Honesty’s the best policy. —Miguel de Cervantes Liars prosper. —Anonymous First Foreword In the early nineties (it might have been 1992, but it’s hard to remember when you’re having a good time) I joined a rock- and-roll band composed mostly of writers.