Short Note: Ritual Washing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Mk 1:44): Jesus, Purity, and the Christian Study of Judaism Paula Fredriksen, Boston University

"Go, show yourself to the priest, and offer for your cleansing what Moses commanded" (Mk 1:44): Jesus, Purity, and the Christian Study of Judaism Paula Fredriksen, Boston University In the last century, and especially in the last few decades, historians of Christianity have increasingly understood Jesus of Nazareth as a participant in the Judaism of his day. Many scholars, however, even when emphasizing Jesus' Jewish ethics, or his Jewish scriptural sensibility, or even the apocalyptic convictions which he shared with so many of his contemporaries, nevertheless draw the line at the biblical laws of purity. These laws rarely appear realistically integrated into an historical reconstruction of Jesus. Allied as they are with the ancient system of sacrifices, they seem obscure to modern religious sensibility; and with the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70, they soon became irrelevant to the later, largely Gentile church. Perhaps, too, such purity codes -- a hallmark of virtually all ancient religions -- are too disturbingly archaic to fit comfortably with modern constructions of Jesus and his message. Very recently, a handful of prominent New Testament historians and theologians have even argued that Jesus taught and acted specifically against the purity codes of his native Judaism. The repudiation of the biblical rules of purity, "the taboos of Torah," stood, they say, at the very heart of Jesus' ministry. Marcus Borg, for example, has urged that Jesus fought the "politics of purity," motivated as he was by a vision of a more compassionate society. Similarly, John Dominic Crossan portrays Jesus as a radical social egalitarian for whom the purity codes of the Temple system were morally and socially anathema. -

Supporting a Person with Washing and Dressing

Factsheet 504LP Supporting a January 2021 person with washing and dressing As a person’s dementia progresses, they will need more help with everyday activities such as washing, bathing and dressing. For most adults, these are personal and private activities, so it can be hard for everyone to adjust to this change. You can support a person with dementia to wash and dress in a way that respects their preferences and their dignity. This factsheet is written for carers. It offers practical tips to help with washing, bathing, dressing and personal grooming. 2 Supporting a person with washing and dressing Contents n How dementia affects washing and dressing — Focusing on the person — Allowing enough time — Making washing and dressing a positive experience — Creating the right environment n Supporting the person with washing and bathing — How to help the person with washing, bathing and showering: tips for carers — Aids and equipment — Skincare and nails — Handwashing and dental care — Washing, drying and styling hair — Hair removal — Using the toilet n Dressing — Helping a person dress and feel comfortable: tips for carers — Shopping for clothes together: tips for carers n Personal grooming — Personal grooming: tips for carers n When a person doesn’t want to change their clothes or wash n Other useful organisations 3 Supporting a person with washing and dressing Supporting a person with washing and dressing How dementia affects washing and dressing The way a person dresses and presents themselves can be an important part of their identity. Getting ready each day is a very personal and private activity – and one where a person may be used to privacy, and making their own decisions. -

Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel

Core Concepts for Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel 1 Presenter Russ Olmsted, MPH, CIC Director, Infection Prevention & Control Trinity Health, Livonia, MI Contributions by Heather M. Gilmartin, NP, PhD, CIC Denver VA Medical Center University of Colorado Laraine Washer, MD University of Michigan Health System 2 Learning Objectives • Outline the importance of effective hand hygiene for protection of healthcare personnel and patients • Describe proper hand hygiene techniques, including when various techniques should be used 3 Why is Hand Hygiene Important? • The microbes that cause healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) can be transmitted on the hands of healthcare personnel • Hand hygiene is one of the MOST important ways to prevent the spread of infection 1 out of every 25 patients has • Too often healthcare personnel do a healthcare-associated not clean their hands infection – In fact, missed opportunities for hand hygiene can be as high as 50% (Chassin MR, Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf, 2015; Yanke E, Am J Infect Control, 2015; Magill SS, N Engl J Med, 2014) 4 Environmental Surfaces Can Look Clean but… • Bacteria can survive for days on patient care equipment and other surfaces like bed rails, IV pumps, etc. • It is important to use hand hygiene after touching these surfaces and at exit, even if you only touched environmental surfaces Boyce JM, Am J Infect Control, 2002; WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care, WHO, 2009 5 Hands Make Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Other Microbes Mobile (Image from CDC, Vital Signs: MMWR, 2016) 6 When Should You Clean Your Hands? 1. Before touching a patient 2. -

WASH Pledge: Guiding Principles a Business Commitment to WASH

WASH Pledge: Guiding principles A business commitment to WASH In collaboration with 22 WASHWASH Pledge:Pledge: GuidingGuiding principlesprinciples Contents Foreword | 4 Summary | 5 Introduction | 6 WBCSD Pledge for access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene | 9 Guiding principles | 10 Guidance on water, sanitation and hygiene at the workplace | 13 WASH at the workplace: points of reference for WASH Pledge self-assessment | 13 1. General 13 2. Workplace water supply 14 3. Workplace sanitation 15 4. Workplace hygiene and behavior change 16 5. Value/supply chain WASH 17 6. Community WASH 17 Educational and behavior change activities | 18 WASH across the value chain | 20 WASH Pledge self-assessment tool for business | 24 3 WASH Pledge: Guiding principles Foreword Today, over 785 million people healthier population and increased and quality, within their operations are still without access to safe productivity.3 and across their value chain, in drinking water, another 2.2 billion all global markets. As employers lack safely managed drinking A proposed first step in and members of society, we water services and an estimated accelerating business action is for encourage businesses to 4.2 billion lack access to safely companies to commit to WBCSD’s commit to the Pledge to ensure managed sanitation services.1 Pledge for Access to Safe Water, appropriate access to safe water, This is incompatible not only Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH sanitation and hygiene for their with the World Business Council Pledge). This Pledge aims to have own employees, thus making a for Sustainable Development’s businesses commit to securing direct contribution to addressing (WBCSD) Vision 2050, where nine appropriate access to safe WASH one of the most pressing public billion people are able to live well for all employees in all premises health challenges of our times. -

Clean Your Hands in the Context of Covid-19

WHO SAVE LIVES: CLEAN YOUR HANDS IN THE CONTEXT OF COVID-19 Hand Hygiene in the Community You can play a critical part in fighting COVID-19 • Hands have a crucial role in the transmission of COVID-19. • COVID-19 virus primarily spreads through droplet and contact transmission. Contact transmission means by touching infected people and/or contaminated objects or surfaces. Thus, your hands can spread virus to other surfaces and/or to your mouth, nose or eyes if you touch them. Why is Hand Hygiene so important in preventing infections, including COVID-19? • Hand Hygiene is one of the most effective actions you can take • Community members can play a critical role in fighting COVID-19 to reduce the spread of pathogens and prevent infections, by adopting frequent hand hygiene as part of their day-to-day including the COVID-19 virus. practices. https://www.who.int/news-room/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/safehands-challengeJoin the #SAFEHANDS challenge now and save lives! Post a video or picture of yourself washing your hands and tag #SAFEHANDS https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/interim-recommendations-on-obligatory-hand-hygiene-against-transmission-of-covid-19WHO calls upon policy makers to provide • the necessary infrastructure to allow people to eectively perform hand hygiene in public places; • to support hand hygiene supplies and best practices in health care facilities. Hand Hygiene in Health Care Why is it important to participate in the WHO global hand hygiene campaign for the fight against COVID-19? • The WHO global hand hygiene campaign SAVEhttps://www.who.int/infection-prevention/campaigns/clean-hands/en/ LIVES: Clean Your Hands mobilizes people around the world to increase adherence to hand hygiene in health care facilities, thus protecting health care workers and patient from COVID-19 and other pathogens. -

E Essence of Purity

112 | על מהות הטהרה !e Essence of Purity e Red Heifer and the Color Wheel One of the great fundamentals revealed in the Torah is the process of shaking off the defilement of death. It is effected via the ashes of the Parah Adumah , the mysterious Red Heifer. By sprinkling a mixture of ashes of a red cow, water and other ingredients upon one who is “impure,” his status changes to “pure.” "e Torah itself calls this process a special chukah, a unique statute, implying that the human intellect cannot properly understand it. Nevertheless, let us try, with the limited means at our disposal, to approach an understanding of some of the sublime concepts embodied in the Red Heifer purification process – if only to fulfill the words of our master and prophet, Moshe Rabbeinu: ִ... <ִי הָוא חְכַמְתֶכ! 1ִבַינְתֶכְ! לֵ:ֵינָי ּהַ:ִמ 9י! ׁאֶש ִר ׁיְש ְמֵע01 אָּת כַל הֻחִּקי! ָּהֵאֶל ְה וָאְמַר1 רַק :ָ! חָכְ! וָנַב0A הADַי ּהָג ַדAל ּהֶזה. ...for [the Torah] is your wisdom and your understanding in the eyes of the nations, who will hea r all these statutes and say, “Only this great nation is a wise and understanding people.” ִ... 1מָי ADי ּג 9דAל ׁאֶש ֻר לA חִּקִי! 1ׁמְש ָּפִטַי! צ ִּדִיקְּ! כַכֹל הAFָרַה ּהזֹאת... ... and which great nation has righteous statutes and ordinances, as this entire Torah? ... (D’varim 4,6-8) The Essence of Purity | Metzora | 113 To this end, we will turn to the physical world, and specifically to the world of color. Let us study the spectrum of the seven colors of the rainbow formed by the diffusion of light rays by drops of water or a prism. -

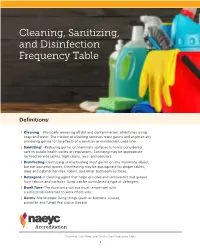

NAEYC Standard 5 (Health), Especially Topic C: Maintaining a Healthful Environment

Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfection Frequency Table Definitions1 › Cleaning2 –Physically removing all dirt and contamination, oftentimes using soap and water. The friction of cleaning removes most germs and exposes any remaining germs to the effects of a sanitizer or disinfectant used later. › Sanitizing3 –Reducing germs on inanimate surfaces to levels considered safe by public health codes or regulations. Sanitizing may be appropriate for food service tables, high chairs, toys, and pacifiers. › Disinfecting–Destroying or inactivating most germs on any inanimate object, but not bacterial spores. Disinfecting may be appropriate for diaper tables, door and cabinet handles, toilets, and other bathroom surfaces. › Detergent–A cleaning agent that helps dissolve and remove dirt and grease from fabrics and surfaces. Soap can be considered a type of detergent. › Dwell Time–The duration a surface must remain wet with a sanitizer/disinfectant to work effectively. › Germs–Microscopic living things (such as bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi) that cause disease. Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfection Frequency Table 1 Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfecting Frequency Table1 Relevant to NAEYC Standard 5 (Health), especially Topic C: Maintaining a Healthful Environment Before After Daily Areas each each (End of Weekly Monthly Comments4 Use Use the Day) Food Areas Clean, Clean, Food preparation Use a sanitizer safe for and then and then surfaces food contact Sanitize Sanitize If washing the dishes and utensils by hand, Clean, use a sanitizer safe -

Euthenics, There Has Not Been As Comprehensive an Analysis of the Direct Connections Between Domestic Science and Eugenics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 Eugenothenics: The Literary Connection Between Domesticity and Eugenics Caleb J. true University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons true, Caleb J., "Eugenothenics: The Literary Connection Between Domesticity and Eugenics" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 730. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/730 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EUGENOTHENICS: THE LITERARY CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTICITY AND EUGENICS A Thesis Presented by CALEB J. TRUE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 2011 History © Copyright by Caleb J. True 2011 All Rights Reserved EUGENOTHENICS: THE LITERARY CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTICITY AND EUGENICS A Thesis Presented By Caleb J. True Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________ Laura L. Lovett, Chair _______________________________ Larry Owens, Member _______________________________ Kathy J. Cooke, Member ________________________________ Joye Bowman, Chair, History Department DEDICATION To Kristina. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Laura L. Lovett, for being a staunch supporter of my project, a wonderful mentor and a source of inspiration and encouragement throughout my time in the M.A. -

Kohelet, Tolstoy and the Red Heifer (Chukat 5780)

בס"ד חקת תש״ף Chukat 5780 Scan (after Shabbat) to join one of Rabbi Sacks’ WhatsApp groups. “With thanks to Te Maurice Wohl Charitable Foundation for their generous sponsorship of Covenant & Conversation. Maurice was a visionary philanthropist. Vivienne was a woman of the deepest humility. Together, they were a unique partnership of dedication and grace, for whom living was giving.” Kohelet, Tolstoy and the Red Heifer The command of the parah adumah, the Red Heifer, with which our parsha begins, is known as the hardest of the mitzvot to understand. The opening words, zot chukat ha-Torah, are taken to mean, this is the supreme example of a chok in the Torah, that is, a law whose logic is obscure, perhaps unfathomable. It was a ritual for the purification of those who had been in contact with, or in, certain forms of proximity to a dead body. A dead body is the primary source of impurity, and the defilement it caused to the living meant that the person so affected could not enter the precincts of the Tabernacle or Temple until cleansed, in a process that lasted seven days. A key element of the purification process involved a Priest sprinkling the person so affected, on the third and seventh day, with a specially prepared liquid known as “the water of cleansing.” First a Red Heifer had to be found, without a blemish, and which had never been used to perform work: a yoke had never been placed on it. This was ritually killed and burned outside the camp. Cedar wood, hyssop, and scarlet wool were added to the fire, and the ashes placed in a vessel containing “living” i.e. -

Mikveh and the Sanctity of Being Created Human

chapter 3 Mikveh and the Sanctity of Being Created Human Susan Grossman This paper was approved by the CJLS on September 13, 2006 by a vote of four- teen in favor, one opposed and four abstaining (14-1-4). Members voting in favor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Elliot Dorff, Aaron Mackler, Robert Harris, Robert Fine, David Wise, Daniel Nevins, Alan Lucas, Joel Roth, Myron Geller, Pamela Barmash, Gordon Tucker, Vernon Kurtz, and Susan Grossman. Members voting against: Rabbi Leonard Levy. Members abstaining: Rabbis Joseph Prouser, Loel Weiss, Paul Plotkin, and Avram Reisner. Sheilah How should we, as modern Conservative Jews, observe the laws tradition- ally referred to under the rubric Tohorat HaMishpahah (The Laws of Family Purity)?1 Teshuvah Introduction Judaism is our path to holy living, for turning the world as it is into the world as it can be. The Torah is our guide for such an ambitious aspiration, sanctified by the efforts of hundreds of generations of rabbis and their communities to 1 The author wishes to express appreciation to all the following who at different stages com- mented on this work: Dr. David Kraemer, Dr. Shaye Cohen, Dr. Seth Schwartz, Dr. Tikva Frymer-Kensky, z”l, Rabbi James Michaels, Annette Muffs Botnick, Karen Barth, and the mem- bers of the CJLS Sub-Committee on Human Sexuality. I particularly want to express my appreciation to Dr. Joel Roth. Though he never published his halakhic decisions on tohorat mishpahah (“family purity”), his lectures and teaching guided countless rabbinical students and rabbinic colleagues on this subject. In personal communication with me, he confirmed that the below psak (legal decision) and reasoning offered in his name accurately reflects his teaching. -

The Techniques of the Sacrifice

Andm Univcrdy Seminary Stndics, Vol. 44, No. 1,13-49. Copyright 43 2006 Andrews University Press. THE TECHNIQUES OF THE SACRIFICE OF ANIMALS IN ANCIENT ISRAEL AND ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA: NEW INSIGHTS THROUGH COMPARISON, PART 1' JOANNSCURLOCK ELMHURSTCOLLEGE Elmhurst, Illinois There is an understandable desire among followers of religions that are monotheistic and that claim descent from ancient Israelite religion to see that religion as unique and completely at odds with its surroundrng polytheistic competitors. Most would not deny that there are at least a few elements of Israelite religion that are paralleled in neighboring cultures, as, e.g., the Hittites: 'I would like to thank the following persons who read and commented on earlier drafts of this article: R. Bed, M. Hilgert, S. Holloway, R. Jas, B. Levine and M. Murrin. Abbreviations follow those given in W. von Soden, AWches Han&rterbuch, 3 301s. (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1965-1981); and M. Jursa and M. Weszeli, "Register Assyriologie," AfO 40-41 (1993/94): 343-369, with the exception of the following: (a) series: D. 0.Edzard, Gnda and His Dynarg, Royal Inscriptions of Mesopommia: Early Periods (RIME) 311 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997); S. Parpola and K. Watanabe, Neo-Assyrin Treatzes and Lq&y Oaths, State Archives of Assyria (SAA) 2 (Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1988); A. Livingstone, Court Poety and Literq Misceubnea, SAA 3 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1989); I. Starr,QnerieJ to the Sungod, SAA 4 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1990); T. Kwasrnan and S. Parpola, Lga/ Trama~~lom$the RoyaiCoz& ofNineveh, Part 1, SAA 6 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1991); F. -

The Law of the Red Heifer: a Type and Shadow of Jesus Christ

Studia Antiqua Volume 4 Number 1 Article 4 April 2005 The Law of the Red Heifer: A Type and Shadow of Jesus Christ Mélbourne O'Banion Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the Biblical Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation O'Banion, Mélbourne. "The Law of the Red Heifer: A Type and Shadow of Jesus Christ." Studia Antiqua 4, no. 1 (2005). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Law of the Red Heifer: A Type and Shadow of Jesus Christ Melbourne O'Banion he law of the red heifer, found in the book of Numbers, chapter 19, is one of the most significant and yet least T understood sacrificial laws in the Old Testament. This law, which governs the purification of those who become ritually unclean by contact with a corpse, was given to the children of Israel to be a "perpetual statute unto them" (Num. 19:21), and, like all other sacrifices, to ultimately point them to the Messiah. Jewish tradition teaches that only Moses knew the full mean ing of this chukkat, or law, which must be obeyed even though not understood. The Midrash says of chukim, "Four Torah laws can not be explained by human reason, but being divine, demand implicit obedience: to marry one's brother's widow (Deut.