Guide to Jewish Cemetery Elements, Prohibitions and How to Conduct a Visit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 91 - Hand Shaking and Seat Switching Ou Israel Center - Summer 2018

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 91 - HAND SHAKING AND SEAT SWITCHING OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2018 A] SHOMER NEGIAH - THE ISSUES • What is the status of the halacha of shemirat negiah - Deoraita or Derabbanan? • What kind of touching does it relate to? What about ‘professional’ touching - medical care, therapies, handshaking? • Which people does it relate to - family, children, same gender? • How does it inpact on sitting close to someone of the opposite gender. Is one required to switch seats? 1. THE WAY WE LIVE NOW: THE ETHICIST. Between the Sexes By RANDY COHEN. OCT. 27, 2002 The courteous and competent real-estate agent I'd just hired to rent my house shocked and offended me when, after we signed our contract, he refused to shake my hand, saying that as an Orthodox Jew he did not touch women. As a feminist, I oppose sex discrimination of all sorts. However, I also support freedom of religious expression. How do I balance these conflicting values? Should I tear up our contract? J.L., New York This culture clash may not allow you to reconcile the values you esteem. Though the agent dealt you only a petty slight, without ill intent, you're entitled to work with someone who will treat you with the dignity and respect he shows his male clients. If this involved only his own person -- adherence to laws concerning diet or dress, for example -- you should of course be tolerant. But his actions directly affect you. And sexism is sexism, even when motivated by religious convictions. -

How Does a Yartzheit 21 Years Ago Feel Like

From: "Rabbi Areyah Kaltmann" <[email protected]> Subject: How does a yartzheit 21 years ago feel like yesterday? Date: June 19, 2015 10:55:32 AM EDT To: "[email protected]" <[email protected]> Reply-To: <[email protected]> Dear Ellie Candle Lighting Times for There are many methods of educating, or passing on a message. Some teachers preach, others speak inspiring New Albany, OH [Based on Zip Code words, and then you have the creative people who use hands-on methods. All these are excellent for 43054]: transmitting information. But when it comes to teaching morality, teaching a way of life, none of these Shabbat Candle Lighting: methods are strong enough. The Rebbe changed many lives, but not by preaching and not by lecturing. He Friday, Jun 19 8:45 pm Shabbat Ends: was simply a living example. His love for each and every Jew and human being, and his self-sacrifice for the Shabbat, Jun 20 9:53 pm ideals of Judaism inspired a whole generation. Torah Portion: Korach This Shabbat marks the 21st Yahrzeit (anniversary of passing) of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson of righteous memory. The day of passing of a holy tzadik is an auspicious day to reflect and bond with the tzadik's soul and to ask the tzadik to intercede on High on our behalf. Therefore, the day of the Rebbe's passing, is an opportune time to pray at the Ohel, the Rebbe's resting place in Queens. Schedule of Services I am I will G-d willing, be at the Ohel this Shabbos together with some tens of thousands of other people from The Lori Schottenstein Chabad Center offers a around the world and I would like to pray for you as well at the Rebbe's "Ohel." If you send me your name and full schedule of Shabbat services. -

Divrei Torah of Rabeinu the Rosh Yeshiva of Ger Shlit"A

בס"ד Divrei Torah of Rabeinu The Rosh Yeshiva of Ger shlit"a Translated into English ז' תמוז תש''פ • יו"ל חקת תשפ"א • נתנדב לזכר נשמת רבינו ה'פני מנחם' זי"ע פרנס החודש חודש תמוז לזכר נשמת כ"ק רבינו הלב שמחה זי"ע יומא דהילולא ז' תמוז לתרומות נא לפנות למכון כמו"כ ניתן לפנות אלינו לקבלת הגליונות מדי שבוע במייל "גחלי אש" "בם חייתני" © כל הזכויות שמורות לשמיעת שיעורים ושיחות בלה"ק ואידיש לשמיעת שיעורים ושיחות בלה"ק ואידיש יוצא לאור ע"י מכון "קול מנחם" מרבינו ראש הישיבה מגור שליט"א מרבותינו הק' זי"ע ומרבני הקהילה מכון להפצת שיעורים ודרשות לשמו ולזכרו בארה"ב - 7162294771 שלוחה 7 לאידיש בארה"ב - 7162294771 שלוחה 8 של רבינו ה"פני מנחם" זי"ע באר"י - 037680292 באר"י - 0772277277 שלוחה 7 לאידיש [email protected] אנגליה - 03303900476 אנגליה - 03303900476 שלוחה 8 בס"ד דברי רבינו ראש הישיבה שליט"א ז' תמוז תש"פ A Yiddishe Home necting to the ruchniyus of the Tzadik. This Connecting To Tzadikim is an avodah that a rashah has no chance at succeeding in, as it is much harder to con- The Gemarah1says, “Tzadikim are greater af- nect to something that is purely spiritual. ter their passing than during their lifetime.” This avodah requires in-depth thinking and The Tosfos explain that this is because analyzation of the Tzadik’s teachings. while a Tzadik is still alive it is possible to connect to the Tzadik through externalities, in a superficial manner. This is why one Chazal2 say, “The words of the Tzadik are sometimes sees wicked people who spend his memorial,” and as such, to connect to a time in the presence of Tzadikim, as they Tzadik through his words and teachings one are connected without a deep internal con- must toil to understand them in as much nection, but rather a purely physical type of depth as one can fathom. -

Understanding Mikvah

Understanding Mikvah An overview of Mikvah construction Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi S. Z. Lesches permission & comments: (514) 737-6076 4661 Van Horne, Suite 12 Montreal P.Q. H3W 1H8 Canada National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Lesches, Schneur Zalman Understanding mikvah : an overview of mikvah construction ISBN 0-9689146-0-8 1. Mikveh--Design and construction. 2. Mikveh--History. 3. Purity, Ritual--Judaism. 4. Jewish law. I. Title. BM703.L37 2001 296.7'5 C2001-901500-3 v"c CONTENTS∗ FOREWORD .................................................................... xi Excerpts from the Rebbe’s Letters Regarding Mikvah....13 Preface...............................................................................20 The History of Mikvaos ....................................................25 A New Design.............................................................27 Importance of a Mikvah....................................................30 Building and Planning ......................................................33 Maximizing Comfort..................................................34 Eliminating Worry ......................................................35 Kosher Waters ...................................................................37 Immersing in a Spring................................................37 Oceans..........................................................................38 Rivers and Lakes .........................................................38 Swimming Pools .........................................................39 -

(Mk 1:44): Jesus, Purity, and the Christian Study of Judaism Paula Fredriksen, Boston University

"Go, show yourself to the priest, and offer for your cleansing what Moses commanded" (Mk 1:44): Jesus, Purity, and the Christian Study of Judaism Paula Fredriksen, Boston University In the last century, and especially in the last few decades, historians of Christianity have increasingly understood Jesus of Nazareth as a participant in the Judaism of his day. Many scholars, however, even when emphasizing Jesus' Jewish ethics, or his Jewish scriptural sensibility, or even the apocalyptic convictions which he shared with so many of his contemporaries, nevertheless draw the line at the biblical laws of purity. These laws rarely appear realistically integrated into an historical reconstruction of Jesus. Allied as they are with the ancient system of sacrifices, they seem obscure to modern religious sensibility; and with the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70, they soon became irrelevant to the later, largely Gentile church. Perhaps, too, such purity codes -- a hallmark of virtually all ancient religions -- are too disturbingly archaic to fit comfortably with modern constructions of Jesus and his message. Very recently, a handful of prominent New Testament historians and theologians have even argued that Jesus taught and acted specifically against the purity codes of his native Judaism. The repudiation of the biblical rules of purity, "the taboos of Torah," stood, they say, at the very heart of Jesus' ministry. Marcus Borg, for example, has urged that Jesus fought the "politics of purity," motivated as he was by a vision of a more compassionate society. Similarly, John Dominic Crossan portrays Jesus as a radical social egalitarian for whom the purity codes of the Temple system were morally and socially anathema. -

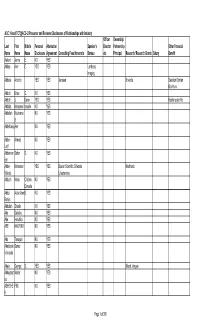

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning

TRANSITIONS & CELEBRATIONS: Jewish Life Cycle Guides E EW A TEMPLE ISRAEL OP HOLLYWOOD Preparing for Jewish Burial and Mourning Written and compiled by Rabbi John L. Rosove Temple Israel of Hollywood INTRODUCTION The death of a loved one is so often a painful and confusing time for members of the family and dear friends. It is our hope that this “Guide” will assist you in planning the funeral as well as offer helpful information on our centuries-old Jewish burial and mourning practices. Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary (“Hillside”) has served the Southern California Jewish Community for more than seven decades and we encourage you to contact them if you need assistance at the time of need or pre-need (310.641.0707 - hillsidememorial.org). CONTENTS Pre-need preparations .................................................................................. 3 Selecting a grave, arranging for family plots ................................................. 3 Contacting clergy .......................................................................................... 3 Contacting the Mortuary and arranging for the funeral ................................. 3 Preparation of the body ................................................................................ 3 Someone to watch over the body .................................................................. 3 The timing of the funeral ............................................................................... 3 The casket and dressing the deceased for burial .......................................... -

Torah in Triclinia: the Rabbinic Banquet and the Significance of Architecture

Theological Studies Faculty Works Theological Studies 2012 Torah in triclinia: the Rabbinic Banquet and the Significance of Architecture Gil P. Klein Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/theo_fac Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Klein, Gil P. "Torah in Triclinia: The Rabbinic Banquet and the Significance of Architecture." Jewish Quarterly Review, vol. 102 no. 3, 2012, p. 325-370. doi:10.1353/jqr.2012.0024. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theological Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T HE J EWISH Q UARTERLY R EVIEW, Vol. 102, No. 3 (Summer 2012) 325–370 Torah in Triclinia: The Rabbinic Banquet and the Significance of Architecture GIL P. KLEIN INASATIRICALMOMENTin Plato’s Symposium (175a), Socrates, who ARTICLES is expected at the banquet, disappears, only to be found lost in thought on the porch of a neighboring house. Similarly, in the Palestinian Talmud (yBer 5.1, 9a), Resh Lakish appears so immersed in thought about the Torah that he unintentionally crosses the city’s Sabbath boundary. This shared trope of the wise man whose introspection leads to spatial disori- entation is not surprising.1 Different as the Platonic philosopher may be -

Burial of a Non Jewish Spouse and Children Rabbi Kassel Abelson Rabbi Loel M

Burial of a Non Jewish Spouse and Children Rabbi Kassel Abelson Rabbi Loel M. Weiss This paper was approved on February 2, 2010, by a vote of ten in favor (10-1-3). Voting in favor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Elliot Dorff, Robert Fine, Susan Grossman, Aaron Mackler, Daniel Nevins, Paul Plotkin Avram Reisner, Loel Weiss, and Steven Wernick. Voting against: Rabbi Miriam Berkowitz. Abstaining: Josh Heller, Rabbis Jay Stein, and David Wise. The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, however, is the authority for the interpretation and application of all matters of halakhah. “We bury non-Jewish dead and comfort their mourners so that we follow the ways of peace” YD 370.1.2010. vkta: May a non-Jewish spouse or children of an interfaith marriage be buried in a separate section of a Jewish Cemetery? If so, what kind of ceremony should it be, and who should officiate at the ceremony? vcua,: These questions are being asked more and more frequently by our colleagues. The growing concern about these questions reflects the growing number of interfaith marriages in our Conservative communities. The Jewish Cemetery in Antiquity In Biblical times burials took place in a burial place owned by the deceased and reserved for members of the family. Abraham bought the cave of Machpelah so that he could bury his wife Sarah in a family burial plot.1 Jacob made his son Joseph swear to bring his body to the land of Canaan so that Jacob could be buried -

Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

The Living Stone: The Talmudic Paradox of the Seventh Month Gestational Viability vs. the Eighth Month Non-Viability Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University December 9, 2020 Miriyam A. Goldman Mentor: Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss, Biology Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Background to Pregnancy ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Talmudic Sources on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………. 6 Meforshim on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Secular Sources of the Dilemma ………………………………………………………………. 11 The Significance of Hair and Nails in Terms of Viability……………………………….……... 14 The Definition of Nefel’s Impact on Viability ……………………………………………….. 17 History of Premature Survival ………………………………………………………………… 18 Statistics on Prematurity ………………………………………………………………………. 19 Developmental Differences Between Seventh and Eighth Months ……………………….…. 20 Contemporary Talmudic Balance of the Dilemma..…………………………………….…….. 22 Contemporary Secular Balance of the Dilemma .……………………………………….…….. 24 Evaluation of Talmudic Accreditation …………………………………………………..…...... 25 Interviews with Rabbi Eitan Mayer, Rabbi Daniel Stein, and Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss .…...... 27 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 29 References…..………………………………………………………………………………..… 34 2 Abstract This paper reviews the viability of premature infants, specifically the halachic status of those born in