Dlis402 : Information Analysis and Repackaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Lisp

1 The Evolution of Lisp Guy L. Steele Jr. Richard P. Gabriel Thinking Machines Corporation Lucid, Inc. 245 First Street 707 Laurel Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142 Menlo Park, California 94025 Phone: (617) 234-2860 Phone: (415) 329-8400 FAX: (617) 243-4444 FAX: (415) 329-8480 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Lisp is the world’s greatest programming language—or so its proponents think. The structure of Lisp makes it easy to extend the language or even to implement entirely new dialects without starting from scratch. Overall, the evolution of Lisp has been guided more by institutional rivalry, one-upsmanship, and the glee born of technical cleverness that is characteristic of the “hacker culture” than by sober assessments of technical requirements. Nevertheless this process has eventually produced both an industrial- strength programming language, messy but powerful, and a technically pure dialect, small but powerful, that is suitable for use by programming-language theoreticians. We pick up where McCarthy’s paper in the first HOPL conference left off. We trace the development chronologically from the era of the PDP-6, through the heyday of Interlisp and MacLisp, past the ascension and decline of special purpose Lisp machines, to the present era of standardization activities. We then examine the technical evolution of a few representative language features, including both some notable successes and some notable failures, that illuminate design issues that distinguish Lisp from other programming languages. We also discuss the use of Lisp as a laboratory for designing other programming languages. We conclude with some reflections on the forces that have driven the evolution of Lisp. -

Hackers and Painters: Big Ideas from the Computer

HACKERS & PAINTERS Big Ideas from the Computer Age PAUL GRAHAM Hackers & Painters Big Ideas from the Computer Age beijing cambridge farnham koln¨ paris sebastopol taipei tokyo Copyright c 2004 Paul Graham. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly & Associates books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (safari.oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected]. Editor: Allen Noren Production Editor: Matt Hutchinson Printing History: May 2004: First Edition. The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. The cover design and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. The cover image is Pieter Bruegel’s Tower of Babel in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. This reproduction is copyright c Corbis. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. ISBN13- : 978 - 0- 596-00662-4 [C] for mom Note to readers The chapters are all independent of one another, so you don’t have to read them in order, and you can skip any that bore you. -

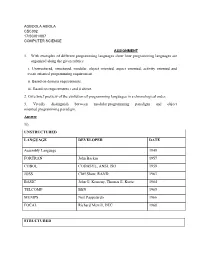

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

NAME: SHOSAN HADIJAT ABIMBOLA MATRIC NO:17/SCI01/076 1I). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN

NAME: SHOSAN HADIJAT ABIMBOLA MATRIC NO:17/SCI01/076 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN JohnBackus 1957 COBOL CODASYL,ANSI,ISO 1959 JOSS CliffShaw,RAND 1963 BASIC JohnG.Kemeny,ThomasE.Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS NeilPappalardo 1966 FOCAL RichardMerrill,DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL58 FriedrichL.Bauer,andco. 1958 ALGOL60 Backus,Bauerandco. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada UnitedStatesDepartmentofDefence 1980 AccentR NIS 1980 Action! OptimizedSystemsSoftware 1983 Alef PhilWinterbottom 1992 DASL SunMicro-systemsLaboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOLW NiklausWirth,TonyHoare 1966 APL LarryBreed,DickLathwellandco. 1966 ALGOL68 A.VanWijngaardenandco. 1968 AMOSBASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin 1990 Stiropoulos AliceML SaarlandUniversity 2000 Agda UlfNorell;Catarinacoquand(1.0) 2007 Arc PaulGraham,RobertMorrisandco. 2008 Bosque MarkMarron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* ThinkingMachine 1987 Actor CharlesDuff 1988 Aldor ThomasJ.WatsonResearchCenter 1990 AmigaE WoutervanOortmerssen 1993 ActionScript Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript AndreasJönsson 2003 Boo RodrigoB.DeOliveria 2003 AmbientTalk Softwarelanguageslab,Universityof Brussels 2006 Axum Microsoft 2009 1ii) a. Scientific Domain LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE FORTRAN JohnBackusandIBM 1950 APT DouglasT.Ross 1956 PL/I IBM 1964 AMPL AMPLOptimization,Inc. 1966 MATLAB MathWorks 1984 J KennethE,Iverson,RogerHui 1990 Ch HarryH.Cheng 2001 Julia JeffBezanson,AlanEdelmanandco. 2012 Cuneiform JörgenBrandt -

1 1. Programacion Declarativa

1. PROGRAMACION DECLARATIVA................................................................. 4 1.1 NUEVOS LENGUAJES. ANTIGUA LÓGICA. ........................................... 4 1.1.1 Lambda Cálculo de Church y Deducción Natural de Grentzen....... 4 1.1.2 El impacto de la lógica..................................................................... 5 1.1.3 Demostradores de teoremas ............................................................. 5 1.1.4 Confianza y Seguridad. .................................................................... 6 1.2 INTRODUCCIÓN A LA PROGRAMACIÓN FUNCIONAL ...................... 7 1.2.1 ¿Qué es la Programación Funcional?............................................... 7 1.2.1.1 Modelo Funcional ................................................................. 7 1.2.1.2 Funciones de orden superior ................................................. 7 1.2.1.3 Sistemas de Inferencia de Tipos y Polimorfismo.................. 8 1.2.1.4 Evaluación Perezosa.............................................................. 8 1.2.2 ¿Qué tienen de bueno los lenguajes funcionales? ............................ 9 1.2.3 Funcional contra imperativo........................................................... 11 1.2.4 Preguntas sobre Programación Funcional...................................... 11 1.2.5 Otro aspecto: La Crisis del Software.............................................. 11 2. HASKELL (Basado en un artículo de Simon Peyton Jones)............................ 13 2.1 INTRODUCCIÓN....................................................................................... -

Report on Common Lisp to the Interlisp Community

Masinter & vanMelle on CommonLisp, circa Dec 1981. Subject: Report on Common Lisp to the Interlisp Community Introduction What is Common Lisp? Common Lisp is a proposal for a new dialect of Lisp, intended be implemented on a broad class of machines. Common Lisp is an attempt to bring together the various implementors of the descendents of the MacLisp dialect of Lisp. The Common Lisp effort is apparently an outgrowth of the concern that there was a lack of coordination and concerted effort among the implementors of the descendents of MacLisp. Common Lisp's principal designers come from the implementors of Lisp Machine Lisp (at MIT and Syrnbolics), Spice Lisp (at CMU), NIL (both a VAX implementation at MIT and the S-1 implementation at Lawrence Livermore), and MacLisp (at MIT, of course.) Also contributing, but not strongly represented, are Standard Lisp (at Utah) and Interlisp (at PARC, BBN and ISI.) Programs written entirely in Common Lisp are supposed to be readily run on any machine supporting Common Lisp. The language is being designed with the intent first of creating a good language, and only secondarily to be as compatible as practical with existing dialects (principally Lisp Machine Lisp.) Common Lisp attempts to draw on the many years of experience with existing Lisp dialects; it tries to avoid constructs that are obviously machine-dependent, yet include constructs that have the possibility of efficient implementation on specific machines. Thus, there are several different goals of Common Lisp: (1)to profit from previous experience in Lisp systems, (2) to make efficient use of new and existing hardware, and (3) to be compatible with existing dialects. -

LM-Prolog the Language and Its Implementation

UPMAIL Technical Report No. 30 . LM-Prolog The Language and Its Implementation Mats Carlsson March 29, 1986 UPMAIL Uppsala Programming Methodology and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Department of Computing Science, Uppsala University P.O. Box 2059 S-750 02 Uppsala Sweden Domestic 018 155400 ext. 1860 International +46 18 111925 Telex 76024 univups s This report was written in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of' Licentiat of Philosophy in Computing Science at Uppsala University. The research reported herein was sponsored by the National Swedish Board for Technical Development (STU). Keywords: Prolog, Logic Programming, Unification, Lisp, :U'unctionaJ Programming, Continuations, Compiling Contents iii lo Introduction o .••••..• o , ...... " ........ " .. " ., •.. ., . o .. " ......... " ..•• o •.. 4 1.1 Overview ....... o .. , ........................................ o •••••••• ., 4 1.2 Language and Computational Model ................................. 4 1.3 Construction of Complex Terms ..................................... 5 1.3.1 Structure Sharing (SS) ......................................... 5 1.3.2 Copying Pure Code (CPO) ....................... ,, .............. 5 1.3.3 Invisible Pointers ........ , .................................... 6 1.3.4 Object and Source Ter1ns ................ , ...................... 6 1.4 Logic Programming in a Functional Setting ............................ 6 1.4.1 Continuation Passing ...... o ••••••• , • " 6 o ................. " ••••• o 7 1.4.2 Realization of Continuations -

From Apis to Languages: Generalising Method Names

From APIs to Languages: Generalising Method Names Michael Homer Timothy Jones James Noble Victoria University of Wellington Victoria University of Wellington Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand New Zealand New Zealand [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The next section gives brief background on the Grace lan- Method names with multiple separate parts are a feature of guage and the motivations for this work. Section 3 describes many dynamic languages derived from Smalltalk. Generalis- the design of generalised method names. Section 4 shows ing the syntax of method names to allow parts to be repeated, and evaluates the application of generalised names within optional, or alternatives, means a single definition can re- our target use cases, and Section 5 describes the extension spond to a whole family of method requests. We show how of an existing Grace implementation to add them. Section 6 generalising method names can support flexible APIs for presents a type-safe modification of the TinyGrace [27] for- domain-specific languages, complex initialisation tasks, and malism to incorporate generalised names into the type sys- control structures defined in libraries. We describe how we tem, while Sections 7, 8, and 9 position this paper among have extended Grace to support generalised method names, related work, suggest future directions, and conclude. and prove that such an extension can be integrated into a gradually-typed language while preserving type soundness. 2. Background Grace is an object-oriented, block-structured, gradually- and Categories and Subject Descriptors D.3.3 [Programming structurally-typed language intended to be used for educa- Languages]: Procedures, functions, and subroutines tion [4]. -

Computing Facilities for AI

AI Magazine Volume 2 Number 1 (1981) (© AAAI) Computino Facilities A Survey of Present and Near-Future Options Scott Fahlman Department of Computer Science Carnegie-Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 At the recent AAAI conference at Stanford, it became isolate the research group from the rest of the AI apparent that many new AI research centers are being community. It seems a much wiser course to tie one’s established around the country in industrial and center in with others, so that tools and results can be governmental settings and in universities that have not shared paid much attention to Al in the past. At the same time, many of the established AI centers are in the process of Of course, this does not mean that one cannot do AI converting from older facilities, primarily based on research on practically any machine if there is no other Decsystem-IO and Decsystem-20 machines, to a variety of choice. Good AI research has been done on machines newer options. At present, unfortunately, there is no from Univac, Burroughs, Honeywell, and even IBM, using simple answer to the question of what machines, operating unbelievably hostile operating systems, and in languages systems, and languages a new or upgrading AI facility ranging from Basic to PL-I. If corporate policy or lack of should use, and this situation has led to a great deal of independent funds forces some such choice on you, it is confusion and anxiety on the part of those researchers and not the end of the world. It should be noted, however, administrators who are faced with making this choice. -

Guide to the Herbert Stoyan Collection on LISP Programming, 2011

Guide to the Herbert Stoyan collection on LISP programming Creator: Herbert Stoyan 1943- Dates: 1955-2001, bulk 1957-1990 Extent: 105 linear feet, 160 boxes Collection number: X5687.2010 Accession number: 102703236 Processed by: Paul McJones with the aid of fellow volunteers John Dobyns and Randall Neff, 2010 XML encoded by: Sara Chabino Lott, 2011 Abstract The Herbert Stoyan collection on LISP programming contains materials documenting the origins, evolution, and use of the LISP programming language and many of its applications in artificial intelligence. Stoyan collected these materials during his career as a researcher and professor, beginning in the former German Democratic Republic (Deutsche Demokratische Republik) and moving to the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland) in 1981. Types of material collected by Stoyan include memoranda, manuals, technical reports, published and unpublished papers, source program listings, computer media (tapes and flexible diskettes), promotional material, and correspondence. The collection also includes manuscripts of several books written by Stoyan and a small quantity of his personal papers. Administrative Information Access Restrictions The collection is open for research. Publication Rights The Computer History Museum (CHM) can only claim physical ownership of the collection. Users are responsible for satisfying any claims of the copyright holder. Permission to copy or publish any portion of the Computer History Museum’s collection must be given by the Computer History Museum. Preferred Citation [Identification of Item], [Date], Herbert Stoyan collection on LISP programming, Lot X5687.2010, Box [#], Folder [#], Computer History Museum Provenance The Herbert Stoyan collection on LISP programming was donated by Herbert Stoyan to the Computer History Museum in 2010. -

Guide to the Herbert Stoyan Collection on LISP Programming

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt038nf156 No online items Guide to the Herbert Stoyan collection on LISP programming Paul McJones with the aid of fellow volunteers John Dobyns and Randall Neff Computer History Museum 1401 N. Shoreline Blvd. Mountain View, California 94043 Phone: (650) 810-1010 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.computerhistory.org © 2011 Computer History Museum. All rights reserved. Guide to the Herbert Stoyan X5687.2010 1 collection on LISP programming Guide to the Herbert Stoyan collection on LISP programming Collection number: X5687.2010 Computer History Museum Processed by: Paul McJones with the aid of fellow volunteers John Dobyns and Randall Neff Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Sara Chabino Lott © 2011 Computer History Museum. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Guide to the Herbert Stoyan collection on LISP programming Dates: 1955-2001 Bulk Dates: 1957-1990 Collection number: X5687.2010 Collector: Stoyan, Herbert Collection Size: 105 linear feet160 boxes Repository: Computer History Museum Mountain View, CA 94043 Abstract: The Herbert Stoyan collection on LISP programming contains materials documenting the origins, evolution, and use of the LISP programming language and many of its applications in artificial intelligence. Stoyan collected these materials during his career as a researcher and professor, beginning in the former German Democratic Republic (Deutsche Demokratische Republik) and moving to the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland) in 1981. Types of material collected by Stoyan include memoranda, manuals, technical reports, published and unpublished papers, source program listings, computer media (tapes and flexible diskettes), promotional material, and correspondence. The collection also includes manuscripts of several books written by Stoyan and a small quantity of his personal papers. -

The Language List - Version 2.4, January 23, 1995

The Language List - Version 2.4, January 23, 1995 Collected information on about 2350 computer languages, past and present. Available online as: http://cui_www.unige.ch/langlist ftp://wuarchive.wustl.edu/doc/misc/lang-list.txt Maintained by: Bill Kinnersley Computer Science Department University of Kansas Lawrence, KS 66045 [email protected] Started Mar 7, 1991 by Tom Rombouts <[email protected]> This document is intended to become one of the longest lists of computer programming languages ever assembled (or compiled). Its purpose is not to be a definitive scholarly work, but rather to collect and provide the best information that we can in a timely fashion. Its accuracy and completeness depends on the readers of Usenet, so if you know about something that should be added, please help us out. Hundreds of netters have already contributed to this effort. We hope that this list will continue to evolve as a useful resource available to everyone on the net with an interest in programming languages. "YOU LEFT OUT LANGUAGE ___!" If you have information about a language that is not on this list, please e-mail the relevant details to the current maintainer, as shown above. If you can cite a published reference to the language, that will help in determining authenticity. What Languages Should Be Included The "Published" Rule - A language should be "published" to be included in this list. There is no precise criterion here, but for example a language devised solely for the compiler course you're taking doesn't count. Even a language that is the topic of a PhD thesis might not necessarily be included.