South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 13 | 2016 Seeing Development As Security: Constructing Top-Down Authority and Inequitab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SI No. File No. Name of the Proposal State Area (Ha) Category View

11/01/2013 View Details PRO PO SALS TO BE DISCUSSED IN THE FO REST ADVISO RY CO MMITTEE MEETING PRO PO SED TO BE CO NVENED O N 21st & 22nd January 2013. Sr. AIGF(Sh. Shiv Pal Singh) SI View File no. Name of the proposal State Area (ha) Category No. Documents sdf 1 8- Diversion of 143.4928 ha of forest Sikkim 143.4928 Hydro Click On 65/2011- land for construction of 520 MW Electric FC Teesta Stage IV hydro electric project in North Distt. of Sikkim by NHPC. 2 8- Diversion of 110.46 ha of forest Arunachal 110.46 Road Click On 42/2012- land in favour of India Army (6th Pradesh FC Battalion Assam Regiment) for infrastructure Development at Naga-GC of Dirang Circle of West Kemeng District of Arunachal Pradesh. 3 8- Diversion of 344.13 ha of forest Arunachal 344.13 Road Click On 68/2012- land for Infrastructure Pradesh FC Development etc. at Mandala (Baisakhi) of West Kemeng District of Arunachal Pradesh in favour of Indian Army. 4 8- Diversion of 78.0131 ha forest Rajasthan 78.0131 Road Click On 88/2012- land for widening of Kishangarh- FC Udaipur-Ahmedabad Section of NH 79A, NH 79, NH 76 and NH 8 from existing 4 lane to 6 lane in the States of Rajasthan and Gujarat in favour of NHAI. 5 8- Diversion of 116.62 ha of forest Arunachal 116.62 Hydel Click On 99/2011- land (Surface forest land = 96.95 Pradesh FC ha and underground area = 19.67 ha) for construction of Tawang H.E. -

Topics in Ho Morphosyntax and Morphophonology

TOPICS IN HO MORPHOPHONOLOGY AND MORPHOSYNTAX by ANNA PUCILOWSKI A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2013 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anna Pucilowski Title: Topics in Ho Morphophonology and Morphosyntax This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Linguistics by: Dr. Doris Payne Chair Dr. Scott Delancey Member Dr. Spike Gildea Member Dr. Zhuo Jing-Schmidt Outside Member Dr. Gregory D. S. Anderson Non-UO Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/ Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii c 2013 Anna Pucilowski iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Anna Pucilowski Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics June 2013 Title: Topics in Ho Morphophonology and Morphosyntax Ho, an under-documented North Munda language of India, is known for its complex verb forms. This dissertation focuses on analysis of several features of those complex verbs, using data from original fieldwork undertaken by the author. By way of background, an analysis of the phonetics, phonology and morphophonology of Ho is first presented. Ho has vowel harmony based on height, and like other Munda languages, the phonological word is restricted to two moras. There has been a long-standing debate over whether Ho and the other North Munda languages have word classes, including verbs as distinct from nouns. -

Consultancy Project Detail

Institute Name IIT KHARAGPUR India Ranking 2017 ID IR17-I-2-18630 Discipline OVERALL ENGG Consultancy Projects Name of faculty (Chief Amount received (in words) S.No. Financial Year Client Organization Title of Consultancy of projectAmount received (in Rupees) PARAMETER Consultant) [Rupees] SOFTLORE SOLUTION-SCIENCE & DEVELOPMENT OF Twenty Two Thousand Four Hundred RAJLAKSHMI 1 2015-16 TECHNOLOGY ENTREPRENEURS PARK, PSYCHOMETRIC 22456 Fifty Six Only GUHA(T0109,RM) 2D.FPPP IIT KHARAGPUR ALGORITHMS Twenty Seven Lakh Sixty Three WATER & SANITATION SUPPORT Thousand Nine Hundred Thirty Only ORGANISATION (WSSO)-DEPARTMENT RIVER WATER QUALITY OF PUBLIC HEALTH ENGINEERING, EVALUATION FOR RIVER 2 2015-16 JAYANTA BHATTACHARYYA(87019,MI), ABHIJIT MUKHERJEE(10018,GG) 2763930 GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL, N.S. BASED PIPED WATER SUPPLY BUILDING, 7TH FLOOR, 1, K. S. ROY SCHEME ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 001 One Lakh Only SRIKRISHNA COLD STORAGE-VILL & P. PROBLEMS OF CULTIVATION O. - NONAKURI BAZAR (KAKTIA BAZAR), 3 2015-16 PROSHANTA GUHA(04016,AG) AND PRESERVATION OF 100000 DISTRICT - PURBA MEDINIPUR, WEST BETEL LEAVES BENGAL - 721172 SUPERINTENDING ENGINEER,- Seventeen Lakh Ten Thousand Only EVALUATION OF FLOOD WESTERN CIRCLE-II, I&W MANAGEMENT SCHEME FOR 4 2015-16 RAJIB MAITY(08039,CE) DIRECTORATE, DIST, PASCHIM 1710000 KELIAGHAI - KAPALESWARI - MEDINIPUR, GOVERNMENT OF WEST BAGHAI RIVER BASIN BENGAL, PIN-721101 ORIENTAL STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS WIDENING & Two Lakh Twenty Four Thousand PVT. LTD.-21, COMMERCIAL STRENGTHENING OF Seven Hundred Twenty Only 5 2015-16 -

Tribal Leadership Programme (TLP) 2019 Participants

Tribal Leadership Programme 2019 Introducing the participants This is to introduce the 101 women and men representing 54 tribes from 21 states of India who are joining us, and the stories that 25 of them are bringing to TLP 2019. The list of participants at TLP 2019… Virendrakumar Uikey Gond Maharashtra Baldev Ram Mandavi Madia Chhattisgarh Bhonjo Singh Banra Ho Jharkhand Falguni Ramesh Bhai Vasava Bhil Gujarat Anil Narve Bhil Madhya Pradesh Hercules Singh Munda Munda Jharkhand Mahendra Mahadya Lohar Varli Maharashtra Pravin Katara Bhil Madhya Pradesh Nikita Soy Ho Jharkhand Sonal N Pardhi Aand Maharashtra Rahul Pendara Bhil Madhya Pradesh Kiran Khalko Oraon Jharkhand Pardip Mukeshbhai Dhodia Dhodia Gujarat Somnath Salam Gond Chhattisgarh Chandramohan Chatomba Ho Jharkhand Shubham Udhay Andhere Kolhati Maharashtra Mahesh Adme Gond Madhya Pradesh Sudam Hembram Santhal Jharkhand Narayan Shivram Jambekar Ojha Maharashtra Neman Markam Gond Madhya Pradesh Bace Buriuly Ho Jharkhand Tejal Rasik Gamit Bhil Gujarat Ramesh Kumar Dhurwe Gond Chhattisgarh Shankar Sen Mahali Mahli Jharkhand Krishna Kumar Bheel Bhil Rajasthan Kalavati Sahani Halba Chhattisgarh Manish Kumar Kharwar Bihar Dipa Samshom Valvi Bhil Maharashtra Gokul Bharti Muria Chhattisgarh Dubeshwar Bediya Bediya Jharkhand Kumar Vinod Bumbidiya Bhil Rajasthan Ritu Pandram Gond Chhattisgarh Manoj Oraon Oraon Jharkhand Pali Lalsu Mahaka Madia Maharashtra Mohan Kirade Bhilala Madhya Pradesh Vibhanshu Kumar Karmali Jharkhand Mita Patel Dhodia Gujarat Jagairam Badole Barela Madhya Pradesh -

Colonial Representations of Adivasi Pasts of Jharkhand, India: the Archives and Beyond

https://books.openedition.org/pressesinalco/23721?lang=en#text Colonial Representations of Adivasi Pasts of Jharkhand, India: the Archives and Beyond Représentations coloniales des passés des Adivasi du Jarkhand, Inde : les archives et au-delà Sanjukta Das Gupta p. 353-362 Abstract Index Text Bibliography Notes Author Abstract English Français Adivasis are the indigenous people of eastern and central India who were identified as “tribes” under British colonial rule and who today have a constitutional status as “Scheduled Tribese. The notion of tribe, despite its evolutionist character, has been internalized to a large extent by the indigenous people themselves and has had a considerable role in shaping community identities. Colonial studies, moreover, were the first systematic investigations into these marginalized and subordinated communities and form an important primary source in historical research on Adivasis. It would be worthwhile, therefore, to identify the main currents of thought that informed and which in turn were reflected in such works. In conclusion, we may argue that rather than a monolithic view, colonial writing encompassed various genres that, despite apparent commonalities, reveal wide divergences over time and space in the manner in which India’s Adivasis were conceptualized and represented. Index terms Mots clés : Asie du Sud, Inde, Jharkhand, XIXe-XXe siècles, Adivasi, colonialisme britannique, Scheduled Tribe Keywords : South Asia, India, 19th-20th centuries, Jharkhand, Adivasi, Bengal, British colonialism, Scheduled Tribe Full text Introduction 1The term “Adivasi” refers to the indigenous people of eastern and central India who are recognized as “Scheduled Tribes” by the Indian Constitution. The notion of “tribe” – introduced in India during colonial times – with its implication of backwardness, geographical isolation, simple technology and racial connotations is problematic, and in recent years it is increasingly replaced, both in academic and popular usage, by adivasi. -

Mission Saranda

MISSION SARANDA MISSION SARANDA A War for Natural Resources in India GLADSON DUNGDUNG with a foreword by FELIX PADEL Published by Deshaj Prakashan Bihar-Jharkhand Bir Buru Ompay Media & Entertainment LLP Bariatu, Ranchi – 834009 © Gladson Dungdung 2015 First published in 2015 All rights reserved Cover Design : Shekhar Type setting : Khalid Jamil Akhter Cover Photo : Author ISBN 978-81-908959-8-9 Price ` 300 Printed at Kailash Paper Conversion (P) Ltd. Ranchi - 834001 Dedicated to the martyrs of Saranda Forest, who have sacrificed their lives to protect their ancestral land, territory and resources. CONTENTS Glossary ix Acknowledgements xi Foreword xvii Introduction 01 1. A Mission to Saranda Forest 23 2. Saranda Forest and Adivasi People 35 3. Mining in Saranda Forest 45 4. Is Mining a Curse for Adivasis? 59 5. Forest Movement and State Suppression 65 6. The Infamous Gua Incident 85 7. Naxal Movement in Saranda 91 8. Is Naxalism Taking Its Last Breath 101 in Saranda Forest? 9. Caught Among Three Sets of Guns 109 10. Corporate and Maoist Nexus in Saranda Forest 117 11. Crossfire in Saranda Forest 125 12. A War and Human Rights Violation 135 13. Where is the Right to Education? 143 14. Where to Heal? 149 15. Toothless Tiger Roars in Saranda Forest 153 16. Saranda Action Plan 163 Development Model or Roadmap for Mining? 17. What Do You Mean by Development? 185 18. Manufacturing the Consent 191 19. Don’t They Rule Anymore? 197 20. It’s Called a Public Hearing 203 21. Saranda Politics 213 22. Are We Indian Too? 219 23. -

Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used by K'ho-Cil

Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by K’Ho-Cil people for treatment of diarrhea in Lam Dong Province, Vietnam Xuan-Minh-Ai Nguyen, Sok-Siya Bun, Evelyne Ollivier, Thi-Phuong-Thao Dang To cite this version: Xuan-Minh-Ai Nguyen, Sok-Siya Bun, Evelyne Ollivier, Thi-Phuong-Thao Dang. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by K’Ho-Cil people for treatment of diarrhea in Lam Dong Province, Vietnam. Journal of Herbal Medicine, Elsevier, 2020, 19, pp.100320. 10.1016/j.hermed.2019.100320. hal-02912504 HAL Id: hal-02912504 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02912504 Submitted on 30 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License ETHNOBOTANICAL STUDY OF MEDICINAL PLANTS USED BY K’HO-CIL PEOPLE FOR TREATMENT OF DIARRHEA IN LAM DONG PROVINCE, VIETNAM Nguyen Xuan Minh AIa,b,*, Sok-Siya BUNb, Evelyne OLLIVIERb, Dang Thi Phuong THAOc aLaboratory of Botany, Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, University of Science, Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. bAix Marseille Univ, Laboratory of Pharmacognosy and Ethnopharmacology, UMR-MD3, Faculty of Pharmacy, France. -

Conservation of the Asian Elephant in Central India

Conserwotion of the Asiqn elephont in Centrql Indiq Sushant Chowdhury Introduction Forests lying in Orissa constitute the major habitats of In central India, elephants are found in the States of elephant in the central India and are distributed across Orissa, Jharkhand (pan of the erstwhile Bihar), and over 22 out of the 27 Forest Divisions. Total elephant southern part of \(est Bengal. In all three States elephants habitat extends over an area of neady 10,000km2, occupy a habitat of approximately 17,000km2 constituted which is about 2lo/o of 47,033km2 State Forest available, by Orissa (57'/), Jharkhand Q6o/o) and southern West assessed through satellite data (FSI 1999). Dense forest Bengal (7"/'). A large number of elephant habitats accounts for 26,073km2, open forest for 20,745km2 in this region are small, degraded and isolated. Land and mangrove for 215km2. \(/hile the nonhern part of fragmentation, encroachment, shifting cultivation and Orissa beyond the Mahanadi River is plagued by severe mining activities are the major threats to the habitats. The mining activities, the southern pan suffers from shifting small fragmented habitats, with interspersed agriculture cultivation. FSI (1999) data reports that the four Districts land use in and around, influence the range extension of of Orissa, namely, Sundergarh, Keonjhar, Jajpur and elephants during the wet season, and have become a cause Dhenkenal, have 154 mining leases of iron, manganese of concern for human-elephant conflicts. Long distance and chromate over 376.6km2 which inclu& 192.6km2 elephant excursions from Singhbhum and Dalbhum of forest. About 5,030km2 (or 8.8olo of total forest area) forests of the Jharkhand State to the adjoining States of is affected by shifting cultivation, most of which is on Chattisgarh (part of erstwhile Madhya Pradesh) and \fest the southern part. -

CUJ Advisor • Prof

ACADEMIA FACULTY PROFILE Central University of Jharkhand, Ranchi (Established by an Act of Parliament of India, 2009) Kkukr~ fg cqfº dkS'kye~ Knowledge to Wisdom Publishers Central University of Jharkhand Brambe, Ranchi - 835205 Chief Patron • Prof. Nand Kumar Yadav 'Indu' Vice-Chancellor, CUJ Advisor • Prof. S.L. Hari Kumar Registrar, CUJ Editors • Dr. Devdas B. Lata, Associate Professor, Department of Energy Engineering • Dr. Gajendra Prasad Singh, Associate Professor, Department of Nano Science and Technology • Mr. Rajesh Kumar, Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication © Central University of Jharkhand From the Vice Chancellor's Desk... t’s a matter of immense pride that the faculty of our Central University of Jharkhand Iare not only teachers of repute but also excellent researchers. They have received national and international recognition and awards for their widely acclaimed papers and works. Their scholarly pursuit reflect the strength of the University and provide ample opportunities for students to carry out their uphill tasks and shape their career. The endeavour of the faculty members to foster an environment of research, innovation and entrepreneurial mindset in campus gives a fillip to collaborate with other academic and other institutions in India and abroad. They are continuously on a lookout for opportunities to create, enrich and disseminate the knowledge in their chosen fields and convert to the welfare of the whole humanity. Continuous introspection and assessment of teaching research and projects add on devising better future planning and innovations. Training and mentoring of students and scholars helps to create better, knowledgeable and responsible citizens of India. I hope this brochure will provide a mirror of strength of CUJ for insiders and outsiders. -

05 Tribal Culture of India Module : 33 Industrialization and Tribe

Paper No. : 05 Tribal Culture of India Module : 33 Industrialization and Tribe Development Team Principal Investigator Prof. Anup Kumar Kapoor Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Paper Coordinator Prof. Anup Kumar Kapoor Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Rajnikant Pandey Content Writer School of Cultural Studies, Centre for Indigenous Cultural Studies, Central University, Jharkhand Content Reviewer Prof. A. Paparao Sri Venkateswar University, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh 1 Tribal Culture of India Anthropology Industrialization and Tribe Description of Module Subject Name Anthropology Paper Name 05 Tribal Culture of India Module Name/Title Industrialization and Tribe Module Id 33 2 Tribal Culture of India Anthropology Industrialization and Tribe CONTENTS OF THIS UNIT: INDUSTRIALIZATION INDUSTRIALIZATION IN INDIA INDUSTRIALIZATION AND TRIBE ANTHROPOLOGY, INDUSTRY AND TRIBE IN INDIA IMPACT OF INDUSTRIALIZATION ON TRIBE INDUSTRIALIZATION AND AFTER SUMMARY 1. LEARNING OUTCOME The focus of present module is to understand the Industrialization in relation to tribal people of India. The module in the beginning takes note of nature of Industrialization in country in different historical phases. After reading this module we will be able to assess both the positive and negative socio- economic impacts of industrialization upon tribal people. The module will also be able to high light the problems and challenges of tribes who are being marginalized because of industry. The module at the end will reflect upon recent conflict over natural resources which are going to affect the future of industrialization in tribal areas. 3 Tribal Culture of India Anthropology Industrialization and Tribe 2. INDUSTRIALIZATION Industrialization is a process of increased emphasis on mechanized production of goods and services through industry. -

1. Name of the Proposal 2. Location I) State Jharkhand Ii) District West Singhbhum 3. Particulars of Forests A) Name of Forest

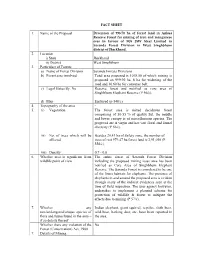

FACT SHEET 1. Name of the Proposal Diversion of 998.70 ha of forest land in Ankua Reserve Forest for mining of iron and manganese ores in favour of M/s JSW Steel Limited in Saranda Forest Division in West Singhbhum district of Jharkhand. 2. Location i) State Jharkhand ii) District West Singhbhum 3. Particulars of Forests a) Name of Forest Division Saranda Forests Divisions b) Forest area involved Total area proposed is 1018.50 of which mining is proposed on 999.90 ha, 8 ha for widening of the road and 10.60 ha for conveyer belt. c) Legal Status/Sy. No Reserve forest and notified as core area of Singhbhum Elephant Reserve (P 56/c). d) Map Enclosed (p-540/c) 4. Topography of the area - 5. (i) Vegetation The forest area is mixed deciduous forest comprising of 50-55 % of quality Sal, the middle and lower canopy is of miscellaneous species. The proposed are is virgin and has vast floral and faunal diversity (P 56/c). (ii) No. of trees which will be Besides 20.43 ha of Safety zone, the number of affected trees of rest 979.47 ha forest land is 2,91,010 (P 556/c). (iii) Density 0.7 - 0.8 6. Whether area is significant from The entire forest of Saranda Forest Division wildlife point of view including the proposed mining lease area has been notified as Core Area of Singhbhum Elephant Reserve. The Saranda Forest is considered to be one of the finest habitats for elephants. The presence of elephants in and around the proposed area is evident through many of the indirect evidences seen at the time of field inspection. -

Education Manual on Indigenous Elders and Engagement With

Education Manual on Indigenous Elders and Engagement with Government Indigenous Learning Institute for Community Empowerment (ILI) Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA) Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) December 2012 2 Education Manual on Indigenous Elders and Engagement with Government Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................1 1 Introduction and Acknowledgements ..........................................................2 2 Training Objectives .....................................................................................5 5 Content Outline ..........................................................................................8 9 Part I. Indigenous Elders and Governance .........................................11 13 Part II. Indigenous Elders in a Changing Society ...............................39 49 Part III. Indigenous Peoples’ Engagement with Local and National Government .....................................................................79 99 Annexes ...............................................................................................125 157 Education Manual on Indigenous Elders and Engagement with Government 3 INTRODUCTION 4 Education Manual on Indigenous Elders and Engagement with Government INTRODUCTION Education Manual on Indigenous Elders and Engagement with Government 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This Education Manual on Indigenous Elders and Engagement with Government is one in a series of leadership