The Greco-Bactrian Mirage: Reconstructing a History of Hellenistic Bactria by Kirk Rappe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits of Empire in Ancient Afghanistan Rule and Resistance in the Hindu Kush, Circa 600 BCE–650 CE

THE LIMITS OF EMPIRE IN ANCIENT AFGHANIStaN RULE AND RESISTANCE IN THE HINDU KUSH, CIRCA 600 BCE–650 CE PROGRAM & ABSTRACTS The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago The Franke Institute for the Humanities October 5–7, 2016 Wednesday, October 5 — Franke Institute Thursday, October 6 — Franke Institute Friday, October 7 — Classics 110 THE LIMITS OF EMPIRE IN ANCIENT AFGHANIStaN RULE AND RESISTANCE IN THE HINDU KUSH, CIRCA 600 BCE–650 CE Organized by Gil J. Stein and Richard Payne The Oriental Institute — The University of Chicago Co-sponsored by the Oriental Institute and the Franke Institute for the Humanities — The University of Chicago PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 5, 2016 — Franke InsTITUTE KEYNOTE LECTURE 5:00 Thomas Barfield “Afghan Political Ecologies: Past and Present” THURSDAY, OCTOBER 6, 2016 — Franke InsTITUTE 8:00–8:30 Coffee 8:30–9:00 Introductory Comments by Gil Stein and Richard Payne SESSION 1: aCHAEMENIDS AND AFTER 9:00–9:45 Matthew W. Stolper “Achaemenid Documents from Arachosia and Bactria: Administration in the East, Seen from Persepolis” 9:45–10:30 Matthew Canepa “Reshaping Eastern Iran’s Topography of Power after the Achaemenids” 10:30–11:00 Coffee Break Cover image. Headless Kushan statue (possibly Kanishka). Uttar Pradesh, India. 2nd–3rd century CE Sandstone 5’3” Government Museum, Mathura. Courtesy Google LIMITS OF EMPIRE 3 SESSION 2: HELLENISTIC AND GRECO-BACTRIAN REGIMES 11:00–11:45 Laurianne Martinez-Sève “Greek Power in Hellenistic Bactria: Control and Resistance” 11:45–12:30 Osmund Bopearachchi “From Royal Greco-Bactrians to Imperial Kushans: The Iconography and Language of Coinage in Relation to Diverse Ethnic and Religious Populations in Central Asia and India” 12:30–2:00 Break SESSIOn 3: KUSHAN IMPERIALISM: HISTORY AND PHILOLOGY 2:00–2:45 Christopher I. -

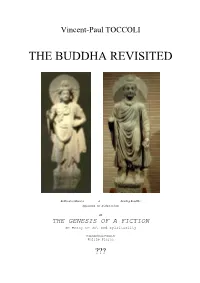

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

Central Asia: Confronting Independence

THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY UNLOCKING THE ASSETS: ENERGY AND THE FUTURE OF CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS CENTRAL ASIA: CONFRONTING INDEPENDENCE MARTHA BRILL OLCOTT SENIOR RESEARCH ASSOCIATE CARNEGIE ENDOWMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE PREPARED IN CONJUNCTION WITH AN ENERGY STUDY BY THE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL ECONOMY AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY – APRIL 1998 CENTRAL ASIA: CONFRONTING INDEPENDENCE Introduction After the euphoria of gaining independence settles down, the elites of each new sovereign country inevitably stumble upon the challenges of building a viable state. The inexperienced governments soon venture into unfamiliar territory when they have to formulate foreign policy or when they try to forge beneficial economic ties with foreign investors. What often proves especially difficult is the process of redefining the new country's relationship with its old colonial ruler or federation partners. In addition to these often-encountered hurdles, the newly independent states of Central Asia-- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-- have faced a host of particular challenges. Some of these emanate from the Soviet legacy, others--from the ethnic and social fabric of each individual polity. Yet another group stems from the peculiarities of intra- regional dynamics. Finally, the fledgling states have been struggling to step out of their traditional isolation and build relations with states outside of their neighborhood. This paper seeks to offer an overview of all the challenges that the Central Asian countries have confronted in the process of consolidating their sovereignty. The Soviet Legacy and the Ensuing Internal Challenges What best distinguishes the birth of the Central Asian states from that of any other sovereign country is the incredible weakness of pro-independence movements throughout the region. -

The Apsidal Temple of Taxila

T HE THE APSIDAL TEMPLE OF TAXILA: A TRADITIONAL HYPOTHESIS AND PSIDA L POSSIBLE NEW INTERPRETATIONS T EMP L E Luca Colliva O F T AXI L A The so called ‘apsidal temple’ of Sirkap is an imposing building belonging, according to Marshall, : T RADI to the Indo-Parthian period (Figure 1) (Marshall 1951, 150-151). It is built over an artificial terrace T facing the main street in the northern part of the town and was brought to light by John Marshall at IONA th the beginning of the last century after some minor excavations during the 19 century. Unlike his L H predecessors, who were very doubtful about its nature (Cunningham 1871, 126-128), Marshall identified YPO T this building as a Buddhist gr. ha-stūpa (Marshall 1930, 111; Marshall 1951, 150); this interpretation HESIS has indeed never been questioned and is accepted, also, in the last study on urban form in Taxila A (Coningham & Edwards 1998, 50). ND However, we cannot deem this attribution certain. No traces are detectable of the main stūpa P OSSIB Marshall recognises in the ‘circular room’ (Marshall 1951, 151). Besides, what Marshall describes as L E two additional stūpas are nothing but scanty remains of foundations belonging to two monuments N of uncertain nature. As I already pointed out in a more exhaustive way (Colliva in press), Marshall EW I was probably convinced that the apsidal shape of this building was enough to identify it as a N T Buddhist caitya. The discovery at Sonkh of an apsidal-shaped temple, probably dedicated to a nāga ERPRE cult, shows, on the contrary, that non-Buddhist religious buildings with an apsidal plan occur in T A T periods chronologically consistent with that of the “apsidal temple” of Sirkap (Härtel 1970; Härtel IONS 1993). -

EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA the Early History of Central Asia Is Gleaned

CHAPTER FOUR EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA KASHGAR TO KHOTAN I. INTRODUCTION The early history of Central Asia is gleaned primarily from three major sources: the Chinese historical writings, usually governmental records or the diaries of the Bud dhist pilgrims; documents written in Kharosthl-an Indian script also adopted by the Kushans-(and some in an Iranian dialect using technical terms in Sanskrit and Prakrit) that reveal aspects of the local life; and later Muslim, Arab, Persian, and Turkish writings. 1 From these is painstakingly emerging a tentative history that pro vides a framework, admittedly still fragmentary, for beginning to understand this vital area and prime player between China, India, and the West during the period from the 1st to 5th century A.D. Previously, we have encountered the Hsiung-nu, particularly the northern branch, who dominated eastern Central Asia during much of the Han period (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), and the Yiieh-chih, a branch of which migrated from Kansu to northwest India and formed the powerful and influential Kushan empire of ca. lst-3rd century A.D. By ca. mid-3rd century the unified Kushan empire had ceased and the main line of kings from Kani~ka had ended. Another branch (the Eastern Kushans) ruled in Gandhara and the Indus Valley, and the northernpart of the former Kushan em pire came under the rule of Sasanian governors. However, after the death of the Sasanian ruler Shapur II in 379, the so-called Kidarites, named from Kidara, the founder of this "new" or Little Kushan Dynasty (known as the Little Yiieh-chih by the Chinese), appear to have unified the area north and south of the Hindu Kush between around 380-430 (likely before 410). -

Central Asia in Xuanzang's Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western

Recording the West: Central Asia in Xuanzang’s Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master Arts in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Laura Pearce Graduate Program in East Asian Studies Ohio State University 2018 Committee: Morgan Liu (Advisor), Ying Zhang, and Mark Bender Copyrighted by Laura Elizabeth Pearce 2018 Abstract In 626 C.E., the Buddhist monk Xuanzang left the Tang Empire for India in a quest to deepen his religious understanding. In order to reach India, and in order to return, Xuanzang journeyed through areas in what is now called Central Asia. After he came home to China in 645 C.E., his work included writing an account of the countries he had visited: The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions (Da Tang Xi You Ji 大唐西域記). The book is not a narrative travelogue, but rather presented as a collection of facts about the various countries he visited. Nevertheless, the Record is full of moral judgments, both stated and implied. Xuanzang’s judgment was frequently connected both to his Buddhist beliefs and a conviction that China represented the pinnacle of culture and good governance. Xuanzang’s portrayal of Central Asia at a crucial time when the Tang Empire was expanding westward is both inclusive and marginalizing, shaped by the overall framing of Central Asia in the Record and by the selection of local legends from individual nations. The tension in the Record between Buddhist concerns and secular political ones, and between an inclusive worldview and one centered on certain locations, creates an approach to Central Asia unlike that of many similar sources. -

Connecting Central Asia

Connecting Central Asia A Road Map for Regional Cooperation Connecting Connecting Central Asia A Road Map for Regional Cooperation Manmohan Parkash A Section of ADB–financed Bishkek–Osh Road © 2006 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2006. Printed in the Philippines. Publication Stock No. 030806 The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Governors, or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors or the Asian Development Bank as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. ii Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms iv Acknowledgment v Foreword vii Introduction 2 The Status of Regional Trade and Transport 6 Trade 6 Transport 8 Railways 10 Road Networks 12 Transport Policies and Plans 16 Main Regional Transport Issues and Options 20 Medium-Term Plans and Priorities for Railways 20 Dislocations 23 Monolithic Organization and Aging Equipment 24 Noncompetitive Marketing and Tariff Setting 25 Medium-Term Plans and Priorities for Road Networks 27 Regulations 28 Border Controls 29 Deteriorating Road Conditions 30 Short-Term Action Plan 32 Regional Rail Integration 33 Restructuring and Modernizing the Railways 34 Regional Road Integration 37 Investment Needs 42 Roads 42 Railways 46 ADB Sector -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note : Geographical landmarks are listed under the proper name itself: for “Cape Sepias” or “Mt. Athos” see “Sepias” or “Athos.” When a people and a toponym share the same base, see under the toponym: for “Thessalians” see “Thessaly.” Romans are listed according to the nomen, i.e. C. Julius Caesar. With places or people mentioned once only, discretion has been used. Abdera 278 Aeaces II 110, 147 Abydus 222, 231 A egae 272–273 Acanthus 85, 207–208, 246 Aegina 101, 152, 157–158, 187–189, Acarnania 15, 189, 202, 204, 206, 251, 191, 200 347, 391, 393 Aegium 377, 389 Achaia 43, 54, 64 ; Peloponnesian Aegospotami 7, 220, 224, 228 Achaia, Achaian League 9–10, 12–13, Aemilius Paullus, L. 399, 404 54–56, 63, 70, 90, 250, 265, 283, 371, Aeolis 16–17, 55, 63, 145, 233 375–380, 388–390, 393, 397–399, 404, Aeschines 281, 285, 288 410 ; Phthiotic Achaia 16, 54, 279, Aeschylus 156, 163, 179 286 Aetoli Erxadieis 98–101 Achaian War 410 Aetolia, Aetolian League 12, 15, 70, Achaius 382–383, 385, 401 204, 250, 325, 329, 342, 347–348, Acilius Glabrio, M. 402 376, 378–380, 387, 390–391, 393, Acragas 119, COPYRIGHTED165, 259–261, 263, 266, 39MATERIAL6–397, 401–404 352–354, 358–359 Agariste 113, 117 Acrocorinth 377, 388–389 Agathocles (Lysimachus ’ son) 343, 345 ; Acrotatus 352, 355 (King of Sicily) 352–355, 358–359; Actium 410, 425 (King of Bactria) 413–414 Ada 297 Agelaus 391, 410 A History of Greece: 1300 to 30 BC, First Edition. Victor Parker. -

Banbhore) (200 Bc to 200 Ad)

INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF SINDH FROM ITS PORT BARBARICON (BANBHORE) (200 BC TO 200 AD) BY M.H. PANHWAR This period covers the rule of Bactrian Greeks, Scythians, Parthians and Kushans in Sindh, rest of the present Pakistan and parts of India. The origins of the development of European trade in the Sindh and trade routes under notice go back to later part of the sixth century BC, and it involved continuous efforts over next seven centuries. (a) After Darius-I’s conquest of Gandhara and Sindhu, admiral Skylax (a Greek of Caryanda), made exploratory voyage down the Kabul and the Indus from Kaspapyrus or Kasyabapura (Peshawar) to the Sindh coast and thence along the Arabian coast to the Red Sea and Egypt in 518 BC, completing the journey in 2 1/2 years and returning to Iran in 514 BC. The voyage was meant to connect the South Asia with Egypt. Darius-I also restored Necho-II’s canal connecting the Nile with the Red Sea. Thus he made Egypt and not Mesopotamia the main line of communication between the Indian and the Mediterranean Oceans. Darius built ‘the Royal Road’ connecting various cities of the empire. It ran the distance of 1677 well-garrisoned miles from Euphesus to Susa. A much longer route than this was from Babylon to Ecbatans and from thence to Kabul, which was already connected with Peshawar. The great voyage of Skylax connected Peshawar with the Red Sea and Egypt, via the Indus and the Arabian Sea. The earlier Egyptian navigation under Pharaohs had purely utilitarian and limited objectives were in no way similar to the great historical voyages, like one by Skylax, for general exploration. -

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions Inaugural Colloquium of the Hellenistic Central Asia Research Network (HCARN) Department of Classics, University of Reading (UK) 15-17 April 2016 ABSTRACTS All conference sessions will be held in Lecture Room G 15, Henley Business School, University of Reading Whiteknights Campus. Baralay, Supratik (University of Oxford) The Arsakids between the Seleucids and the Achaemenids Abstract pending. Bordeaux, Olivier (Paris-Sorbonne) Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek numismatics: Methodologies, new research and limits Numismatics is one of the leading fields in Hellenistic Central Asia studies, since it has enabled historians to identify 45 different Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kings, while written sources only speak of 10. The coins struck by the Greek kings are often remarkable, both because of their quality and the multiple innovations some of them show: Indian iconography, local language (Brahmi or Kharoshthi), new weight system, etc. Yet, broad studies by properly trained numismatists still remained scarce, while new coins mainly find their origin on the art market rather than archaeological digs. The current situation in Central Asia, especially in Afghanistan and Pakistan, does not help archaeologists to broaden their fieldwork. Die-studies are more and more often the methodology followed by the numismatists in the last decade, so as to draw as much data as possible from large corpora. During our PhD research, we focused on six kings: Diodotus I and II, Euthydemus I, Eucratides I, Menander I and Hippostratus. Beyond individual results and hypothesis, we tried to ascertain this particular methodology regarding Central Asia Greek coinages. Generally, our die-studies provided good outcomes, while most of our attempts to geographically locate mints or even borders remain quite fragile, in the lack of archaeological data. -

An Archaeological Analysis of Early Buddhism and the Mauryan Empire at Lumbini, Nepal

Durham E-Theses The Mauryan Horizon: An Archaeological Analysis of Early Buddhism and the Mauryan Empire at Lumbini, Nepal TREMBLAY, JENNIFER,CARRIE How to cite: TREMBLAY, JENNIFER,CARRIE (2014) The Mauryan Horizon: An Archaeological Analysis of Early Buddhism and the Mauryan Empire at Lumbini, Nepal , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11038/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract The Mauryan Horizon: An Archaeological Analysis of early Buddhism and the Mauryan Empire at Lumbini, Nepal Jennifer Carrie Tremblay The archaeology of Buddhism in South Asia is reliant on the art historical study of monumental remains, the identification of which is tied to the textual historical sources that dominate Buddhist scholarship. The development and spread of early Buddhism from the third century BCE has been intrinsically linked with the Mauryan Emperor Asoka, and is consequently reliant on the identification of ‘Mauryan’ remains in the archaeological record.