Article Full Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antique Japanese Swords for Sale

! Antique Japanese Swords For Sale As of October 24, 2012 Tokyo, Japan The following pages contain descriptions of genuine antique Japanese swords currently available for ownership. Each sword can be legally owned and exported outside of Japan. Descriptions and availability are subject to change without notice. Please enquire for additional images and information on swords of interest to [email protected]. We look forward to assisting you. Pablo Kuntz Founder, unique japan Unique Japan, Fine Art Dealer Antiques license issued by Meguro City Tokyo, Japan (No.303291102398) Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Index of Japanese Swords for Sale # SWORDSMITH & TYPE CM CERTIFICATE ERA / PERIOD PRICE 1 A SADAHIDE GUNTO 68.0 NTHK Kanteisho 12th Showa (1937) ¥510,000 2 A KANETSUGU KATANA 73.0 NTHK Kanteisho Gendaito (~1940) ¥495,000 3 A KOREKAZU KATANA 68.7 Tokubetsu Hozon Shoho (1644~1648) ¥3,200,000 4 A SUKESADA KATANA 63.3 Tokubetsu Kicho 17th Eisho (1520) ¥2,400,000 5 A ‘FUYUHIRO’ TACHI 71.6 NTHK Kanteisho Tenbun (1532~1555) ¥1,200,000 6 A TADAKUNI KATANA 65.3 NBTHK Hozon Jokyo (1684~1688) ¥1,150,000 7 A MORIIE KATANA 71.0 NBTHK Hozon Eisho (1504~1521) ¥1,050,000 HOLD A TAKAHIRA KATANA 69.7 Tokubetsu Kicho 5th Kanai (1628) 9 A NOBUHIDE KATANA 72.1 NTHK Kanteisho 2nd Bunkyu (1862) ¥2,500,000 10 A KIYOMITSU KATANA 67.6 NBTHK Hozon 2nd Eiroku (1559) ¥2,500,000 SOLD A KANEUJI KATANA 69.8 NTHK Kanteisho Kyoho (1716~1735) ¥2,000,000 12 A NAOTSUNA KATANA 61.8 NTHK Kanteisho Oei (1394~1427) ¥600,000 13 A YOSHIKUNI KATANA 69.0 Keian (1648~1651) -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’S Daughters – Part 2

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 8. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Abstract This section discusses the complex psychological and philosophical reason for Shogun Yoshimune’s contrasting handlings of his two adopted daughters’ and his favorite son’s weddings. In my thinking, Yoshimune lived up to his philosophical principles by the illogical, puzzling treatment of the three weddings. We can witness the manifestation of his modest and frugal personality inherited from his ancestor Ieyasu, cohabiting with his strong but unconventional sense of obligation and respect for his benefactor Tsunayoshi. Disciplines Family, Life Course, and Society | Inequality and Stratification | Social and Cultural Anthropology This is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 Weddings of Shogun’s Daughters #2- Seigle 1 11Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 e. -

View Checklist

Mountains and Rivers: Scenic Views of Japan, July 10, 2009-November 1, 2009 The landscape has long been an important part of Japanese art and literature. It was first celebrated in poetry, where invoking the name of a famous location, or meisho, was meant to summon a certain feeling. Later, paintings of these same locations would bring to mind their well-known poetic and literary history. Together, the poems and imagery comprised a canon of place and sentiment, as the same meisho were rendered again and again. During the Edo period (1603–1868) the landscape genre, initially available only to the elite, spread to the medium of woodblock printing, the art of commoner culture. In the 19th century, when most of the works in this exhibition were made, several factors led to the rise of the landscape genre in woodblock prints. Up to this time, the staples of the woodblock print medium had been images of beautiful courtesans and handsome kabuki theater actors. First among these factors was the rising popularity of domestic travel. The development of a system of major roads allowed many people to travel for both business and pleasure. Woodblock prints of locations along these travel routes could function as souvenirs for those who made the trip or as fantasy for those who could not. Rather than evoking a poetic past, these images of meisho were meant to tantalize viewers into imagining romantic far-off places. Another factor in the growth of the genre was the skill of two particular woodblock print artists— Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) (whose works are heavily represented here). -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods: vast majority, who were based in urban centers, could ill afford to be indifferent to money and the Diaries of the Toyama Family commerce. Largely divorced from the land and of Hachinohe incumbent upon the lord for their livelihood, usually disbursed in the form of stipends, samu- © Constantine N. Vaporis, University of rai were, willy-nilly, drawn into the commercial Maryland, Baltimore County economy. While the playful (gesaku) literature of the late Tokugawa period tended to portray them as unrefined “country samurai” (inaka samurai, Introduction i.e. samurai from the provincial castle towns) a Samurai are often depicted in popular repre- reading of personal diaries kept by samurai re- sentations as indifferent to—if not disdainful veals that, far from exhibiting a lack of concern of—monetary affairs, leading a life devoted to for monetary affairs, they were keenly price con- the study of the twin ways of scholastic, meaning scious, having no real alternative but to learn the largely Confucian, learning and martial arts. Fu- art of thrift. This was true of Edo-based samurai kuzawa Yukichi, reminiscing about his younger as well, despite the fact that unlike their cohorts days, would have us believe that they “were in the domain they were largely spared the ashamed of being seen handling money.” He forced paybacks, infamously dubbed “loans to maintained that “it was customary for samurai to the lord” (onkariage), that most domain govern- wrap their faces with hand-towels and go out ments resorted to by the beginning of the eight- after dark whenever they had an errand to do” in eenth century.3 order to avoid being seen engaging in commerce. -

1. Outlines and Characteristics of the Great East Japan Earthquake

The Great East Japan Earthquake Report on the Damage to the Cultural Heritage A ship washed up on the rooft op of an building by Tsunami (Oduchi Town, Iwate Prefecture ) i Collapsed buildings (Kesennuma City, Miyagi Prefecture ) ii Introduction The Tohoku Earthquake (East Japan Great Earthquake) which occurred on 11th March 2011 was a tremendous earthquake measuring magnitude 9.0. The tsunami caused by this earthquake was 8-9m high, which subsequently reached an upstream height of up to 40m, causing vast and heavy damage over a 500km span of the pacifi c east coast of Japan (the immediate footage of the power of such forces now being widely known throughout the world). The total damage and casualties due to the earthquake and subsequent tsunami are estimated to be approximately 19,500 dead and missing persons; in terms of buildings, 115,000 totally destroyed, 162,000 half destroyed, and 559,000 buildings being parti ally destroyed. Immediately aft er the earthquake, starti ng with President Gustavo Araoz’s message enti tled ‘ICO- MOS expresses its solidarity with Japan’, we received warm messages of support and encourage- ment from ICOMOS members throughout the world. On behalf of Japan ICOMOS, I would like to take this opportunity again to express our deepest grati tude and appreciati on to you all. There have been many enquiries from all over the world about the state of damage to cultural heritage in Japan due to the unfolding events. Accordingly, with the cooperati on of the Agency for Cultural Aff airs, Japan ICOMOS issued on 22nd March 2011 a fi rst immediate report regarding the state of Important Cultural Properti es designated by the Government, and sent it to the ICOMOS headquarters, as well as making it public on the Japan ICOMOS website. -

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Timelines and Maps Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books English Version © Keio University Timelines and Maps East Asian History at a Glance Books are part of the flow of history. But it is not only about Japanese history. Many books travel over the sea time to time for several reasons and a lot of knowledge and information comes and go with books. In this course, you’ll see books published in Japan as well as ones come from China and Korea. Let’s take a look at the history in East Asia. You do not have to remember the names of the historical period but please refer to this page for reference. Japanese History Overview This is a list of the main periods in Japanese history. This may be a useful reference as we proceed in the course. Period Name of Era Name of Era - mid-3rd c. CE Yayoi 弥生 mid-3rd c. CE - 7th c. CE Kofun (Tomb period) 古墳 592 - 710 Asuka 飛鳥 710-794 Nara 奈良 794 - 1185 Heian 平安 1185 - 1333 Kamakura 鎌倉 Nanboku-chō 1333 - 1392 (Southern and Northern Courts period) 南北朝 1392 - 1573 Muromachi 室町 1573 - 1603 Azuchi-Momoyama 安土桃山 1603 - 1868 Edo 江戸 1868 - 1912 Meiji 明治 Era names (Nengō) in Edo Period There were several era names (nengo, or gengo) in Edo period (1603 ~ 1868) and they are sometimes used in the description of the old books and materials, especially Week 2 and Week 4. Here is the list of the era names in Edo period for your convenience; 1 SINO-JAPANESE INTERACTIONS THROUGH RARE BOOKS KEIO UNIVERSITY © Keio University Timelines and Maps Start Era name English Start Era name English 1596 慶長 Keichō 1744 延享 Enkyō -

Guts and Tears Kinpira Jōruri and Its Textual Transformations

Guts and Tears Kinpira Jōruri and Its Textual Transformations Janice Shizue Kanemitsu In seventeenth-century Japan, dramatic narratives were being performed under drastically new circumstances. Instead of itinerant performers giving performances at religious venues in accordance with a ritual calendar, professionals staged plays at commercial, secular, and physically fixed venues. Theaters contracted artists to perform monthly programs (that might run shorter or longer than a month, depending on a given program’s popularity and other factors) and operated on revenues earned by charging theatergoers admission fees. A theater’s survival thus hinged on staging hit plays that would draw audiences. And if a particular cast of characters was found to please crowds, producing plays that placed the same characters in a variety of situations was one means of ensuring a full house. Kinpira jōruri 金平浄瑠璃 enjoyed tremendous though short-lived popularity as a form of puppet theater during the mid-1600s. Though its storylines lack the nuanced sophistication of later theatrical narra- tives, Kinpira jōruri offers a vivid illustration of how theater interacted with publishing in Japan during the early Tokugawa 徳川 period. This essay begins with an overview of Kinpira jōruri’s historical background, and then discusses the textualization of puppet theater plays. Although Kinpira jōruri plays were first composed as highly masculinized period pieces revolving around political scandals, they gradually transformed to incorporate more sentimentalism and female protagonists. The final part of this chapter will therefore consider the fundamental characteristics of Kinpira jōruri as a whole, and explore the ways in which the circulation of Kinpira jōruri plays—as printed texts— encouraged a transregional hybridization of this theatrical genre. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48194-6 — Japan's Castles Oleg Benesch , Ran Zwigenberg Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48194-6 — Japan's Castles Oleg Benesch , Ran Zwigenberg Index More Information Index 10th Division, 101, 117, 123, 174 Aichi Prefecture, 77, 83, 86, 90, 124, 149, 10th Infantry Brigade, 72 171, 179, 304, 327 10th Infantry Regiment, 101, 108, 323 Aizu, Battle of, 28 11th Infantry Regiment, 173 Aizu-Wakamatsu, 37, 38, 53, 74, 92, 108, 12th Division, 104 161, 163, 167, 268, 270, 276, 277, 12th Infantry Regiment, 71 278, 279, 281, 282, 296, 299, 300, 14th Infantry Regiment, 104, 108, 223 307, 313, 317, 327 15th Division, 125 Aizu-Wakamatsu Castle, 9, 28, 38, 62, 75, 17th Infantry Regiment, 109 77, 81, 277, 282, 286, 290, 311 18th Infantry Regiment, 124, 324 Akamatsu Miyokichi, 64 19th Infantry Regiment, 35 Akasaka Detached Palace, 33, 194, 1st Cavalry Division (US Army), 189, 190 195, 204 1st Infantry Regiment, 110 Akashi Castle, 52, 69, 78 22nd Infantry Regiment, 72, 123 Akechi Mitsuhide, 93 23rd Infantry Regiment, 124 Alnwick Castle, 52 29th Infantry Regiment, 161 Alsace, 58, 309 2nd Division, 35, 117, 324 Amakasu Masahiko, 110 2nd General Army, 2 Amakusa Shirō , 163 33rd Division, 199 Amanuma Shun’ichi, 151 39th Infantry Regiment, 101 American Civil War, 26, 105 3rd Cavalry Regiment, 125 anarchists, 110 3rd Division, 102, 108, 125 Ansei Purge, 56 3rd Infantry Battalion, 101 anti-military feeling, 121, 126, 133 47th Infantry Regiment, 104 Aoba Castle (Sendai), 35, 117, 124, 224 4th Division, 77, 108, 111, 112, 114, 121, Aomori, 30, 34 129, 131, 133–136, 166, 180, 324, Aoyama family, 159 325, 326 Arakawa -

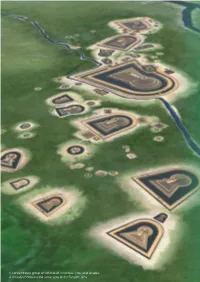

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

Hiraizumi Kiyoshi (1895-1984): 'Spiritual History' in the Service of the Nation In Twentieth Century Japan By Kiyoshi Ueda A Thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, in the University of Toronto © Copyright by Kiyoshi Ueda, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44743-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44743-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation.