Italian Communist Party, 1947-1951

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pages 4 Rotella, Lot 51 Pagine

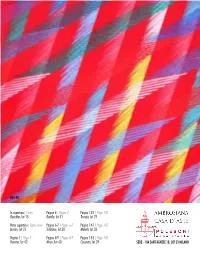

LOT 42 In copertina | Cover Pagine 4 | Pages 4 Pagina 133 | Page 133 Baechler, lot 15 Rotella, lot 51 Turcato, lot 29 Retro copertina | Back cover Pagine 6-7 | Pages 6-7 Pagina 142 | Page 142 Arman, lot 25 Schifano, lot 30 Melotti, lot 33 Pagina 1 | Page 1 Pagine 8-9 | Pages 8-9 Pagina 143 | Page 143 Dorazio, lot 42 Music, lot 60 Cassinari, lot 39 SEDE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18, 20123 MILANO ASTA ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 – presso LA POSTERIA 23 OTTOBRE - 4 NOVEMBRE, MILANO VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 0 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00 – ESCLUSO FESTIVI E 29 OTTOBRE) PREVIO APPUNTAMENTO 7-8-9 NOVEMBRE, MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00) UNICA SESSIONE MARTEDÌ 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 16.00 LOTTI 1 - 243 PRESENTAZIONE TELEVISIVA TOP LOTS Lunedì 2/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Martedì 3/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Giovedì 5/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Venerdì 6/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre OFFERTE SCRITTE FINO A LUNEDÌ 9 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 15.00 FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] È possibile partecipare in diretta on-line inscrivendosi (almeno 24 ore prima) sul nostro sito www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CONSULTAZIONE CATALOGO E MODULISTICA www.ambrosianacasadaste.com da venerdì 23 ottobre 2020 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. +39 0289459708 - FAX +39 0240703717 www.ambrosianacasadaste.com • [email protected] LOT 51 338 1226703 5 MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART -

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

W E L C O M E T O B O C C O

International Relations WELCOME TO BOCCONI Life at Bocconi Luigi Bocconi Università Commerciale WELCOME TO BOCCONI PART II: LIFE AT BOCCONI WELCOME TO BOCCONI Life at Bocconi INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________5 Bocconi University Internationalisation in figures Bocconi International perspective Academic Information Glossary for Students LIVING IN BOCCONI ISD ____________________________________________________________________________8 International Student Desk Welcome Desk Buddy Service University Tour Bocconi Welcome Kit Day Trips Italian Language Course What's on in Milan Cocktail for International Students HOUSING ______________________________________________________________________9 How can I pay my rent? How can I have my deposit back? USEFUL INFORMATION ________________________________________________________10 ID Card Punto Blu, Virtual Punto Blu and Internet points Certificates Bocconi E-mail and yoU@B Official Communications Meals Computer Rooms Access the Bocconi Computer Network with your own laptop Mailboxes Bookstore ACADEMIC INFORMATION ______________________________________________________15 Study Plan Exams Transcript - Only for Exchange Students SERVICES ____________________________________________________________________19 International Recruitment Service Library Language Centre ISU Bocconi (Student Assistance and Financial Aid) Working in Italy and abroad CESDIA SCHOLARSHIPS AND LOANS __________________________________________________20 ANNEX 1: Exchange Students __________________________________________________21 -

The Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti

From Page to Screen: the Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti Lucia Di Rosa A thesis submitted in confomity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) Graduate Department of ltalian Studies University of Toronto @ Copyright by Lucia Di Rosa 2001 National Library Biblioth ue nationale du Cana2 a AcquisitTons and Acquisitions ef Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WeOingtOn Street 305, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Otiawa ON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence ailowing the exclusive ~~mnettantà la Natiofliil Library of Canarla to Bibliothèque nation& du Canada de reprcduce, loan, disûi'bute or seil reproduire, prêter, dishibuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format é1ectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation, From Page to Screen: the Role of Literatuce in the Films af Luchino Vionti By Lucia Di Rosa Ph.D., 2001 Department of Mian Studies University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation focuses on the role that literature plays in the cinema of Luchino Visconti. The Milanese director baseci nine of his fourteen feature films on literary works. -

Carla Accardi Biography

SPERONE WESTWATER 257 Bowery New York 10002 T + 1 212 999 7337 F + 1 212 999 7338 www.speronewestwater.com Carla Accardi Biography 1924 Born Trapani, Sicily 2014 Died Rome, Italy One Person Exhibitions: 1950 “Carla Accardi. 15 Tempere,” Galleria Age d’Or, Rome, 16 November – 1 December 1951 “Accardi e Sanfilippo,” Libreria Salto, Milan, 31 March – 6 April (catalogue) 1952 “Carla Accardi,” Galleria Ill Pincio, Rome (catalogue) “Mostra personale della pittrice Carla Accardi,” Galleria d’Arte Contemporanea, Florence (catalogue) “Carla Accardi-Antonio Sanfilippo,” Galleria Il Cavallino, Venice, 5 – 23 July (catalogue) 1955 “Accardi,” Galleria San Marco, Rome, 16 – 30 June 1956 “Peintures de Accardi - Sculptures de Delahaye,” Galerie Stadler, Paris, 18 February – 8 March (catalogue) 1957 “Accardi,” Galleria Dell’Ariete, Milan (catalogue) 1958 “Carla Accardi,” Galleria La Salita, Rome “Carla Accardi. Peintures récentes,” Galeria L’Entracte, Lausanne, Switzerland 1959 “Dipinti e tempere di Carla Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin (catalogue) “Accardi. Opere recenti,” Galleria La Salita, Rome 1960 “Dipinti di Carla Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin (catalogue) 1961 “Carla Accardi,”Galleria La Salita, Rome “Carla Accardi,” Parma Gallery, New York, 23 May – 10 June “Carla Accardi: Recent Paintings,” New Vision Centre, London, 5 – 24 June 1964 “Italian Pavilion – Solo Room, ” curated by Carla Lonzi, XXXII Biennale di Venezia, Venice, 20 July – 18 October (catalogue) “Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin, 16 October – 15 November (catalogue) 1965 Galleria -

69. Il Novecento (15)

Blitz nell’arte figurativa 69. Il Novecento (15) Il linguaggio figurativo trovò maggiore spazio nell’Espressionismo, opponendosi al Dada che tanta parte ebbe, e ha tuttora, nell’arte moderna, soprattutto in versione Surrealista. Però, la figurazione adattata ai nuovi concetti si caricò di una responsabilità che appare superiore a quella dei tardi dadaisti. In particolare modo, gli Espressionisti moderni, attivi fra le due guerre mondiali e maggiormente dopo la Seconda, cercarono punti di riferimento precisi, sconosciuti ai cultori dell’onirismo. Questi ultimi hanno avuto, e hanno ancora, il pregio di presentare varie suggestioni e dunque varie possibilità di aprirsi a un reale privo di finalismo e di determinismo. La relatività delle cose non è un vicolo cieco, bensì la chance di aprire nuovi orizzonti. Come rovescio della medaglia, abbiamo spesso una sorta di resa a questo programma che, infatti, diventa un manierismo destinato all’inefficienza. Il linguaggio figurativo tradizionale è invece costretto a cercare punti di appoggio e, insieme a una specie di possibile chiusura, esso offre visioni che richiedono profonde riflessioni: magari banali anche nella consistenza, talvolta però più incisive e prolifiche di quanto costatabile e ipotizzabile. Si dimostra che la manipolazione della figura, fatta non a caso, fatta cioè non seguendo il mito del gesto, può arricchire la dinamicità dell’alfabeto usato dalle arti figurative dalla notte dei tempi. A questo punto, ispirazione Dada e rigore analitico perseguito con mezzi classici, trovano contatti, pur se solo raramente riescono a condizionarsi a vicenda. La finalità è la conoscenza possibile e probabile. Si tratta di una conoscenza nuova che chiama in causa l’intera personalità umana scaturita da esperienze pratiche, molto avanzate rispetto al passato, e da interrogativi sentimentali eterni che ora reclamano una risposta: talvolta, negli animi più sensibili e attenti, in modo disperato, per quanto mascherato da una sicurezza formale o semplicemente esecutiva. -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

Italiani a Parigi

italiani a Parigi Da Severini a S a v i n i o Da De ChiriCo a CamPigli Birolli Boldini Bucci campigli de chirico de pisis levi magnelli m e n z i o m o d i g l i a n i p a r e s c e pirandello prampolini rossi savinio severini soffici Tozzi zandomeneghi ItalIanI a ParIgI D a S e v e r I n I a S AVI n IO Da De ChIrico a CaMPIGLI Bergamo, 10 - 30 maggio 2014 Palazzo Storico Credito Bergamasco Curatori Angelo Piazzoli Paola Silvia Ubiali Progetto grafico Drive Promotion Design Art Director Eleonora Valtolina Indicazioni cromatiche VERDE BLU ROSSO C100 M40 Y100 C100 M80 Y20 K40 C40 M100 Y100 PANTONE 349 PANTONE 281 PANTONE 187 R39 G105 B59 R32 G45 B80 R123 G45 B41 ItalIanI a ParIgI Da Severini a SAVINIO Da De Chirico a Campigli p r e C u r so r i e D e r e D i Opere da collezioni private Birolli, Boldini, Bucci Campigli, de Chirico de Pisis, Levi, Magnelli Menzio, Modigliani Paresce, Pirandello Prampolini, Rossi Savinio, Severini, Soffici Tozzi, Zandomeneghi 1 I g ri a P a P r e f a z I o n e SaggIo CrItICo I a n li a T I 2 P r e f a z I o n e SaggIo CrItICo 3 Italiani a Parigi: una scoperta affascinante Nelle ricognizioni compiute tra le raccolte private non abbiamo incluso invece chi si mosse dall’Italia del territorio, nell’intento di reperire le opere che soltanto per soggiorni turistici o per brevi comparse. -

Villa Wolkonsky Leonardo in Milan the Renzi Government Guttuso at the Estorick Baron Corvo in Venice

Villa Wolkonsky Leonardo in Milan The Renzi Government Guttuso at the Estorick RIVISTA Baron Corvo in Venice 2015-2016 The Magazine of Dear readers o sooner had we consigned our first Rivista to the in their city. We hope that you too will make some printers, than it was time to start all over again. discoveries of your own as you make your way through the NStaring at a blank piece of paper, or more accurately pages that follow. an empty screen and wondering where the contributions We are most grateful for the positive feedback we received are going to come from is a daunting prospect. But slowly from readers last year and hope that this, our second issue, the magazine began to take shape; one or two chance will not disappoint. encounters produced interesting suggestions on subjects Buona lettura! we knew little or nothing about and ideas for other features developed from discussion between ourselves and British Linda Northern and Vanessa Hall-Smith Italian Society members. Thank you to all our contributors. And as the contributions began to arrive we found some unlikely connections – the Laocoon sculpture, the subject of an excellent talk which you can read about in the section dedicated to the BIS year, made a surprise appearance in a feature about translation. The Sicilian artist, Renato Guttoso, an exhibition of whose work is reviewed on page 21, was revealed as having painted Ian Greenlees, a former director of the British Institute of Florence, whose biography is considered at page 24. We also made some interesting discoveries, for example that Laura Bassi, an 18th century mathematician and physicist from Bologna, was highly regarded by no less a figure than Voltaire and that the Milanese delight in finding unusual nicknames for landmarks Vanessa Hall-Smith Linda Northern Cover photo: Bastoni in a Sicilian pack of cards. -

Italian Painting in Between the Wars at MAC USP

MODERNIDADE LATINA Os Italianos e os Centros do Modernismo Latino-americano Classicism, Realism, Avant-Garde: Italian Painting In Between The Wars At MAC USP Ana Gonçalves Magalhães This paper is an extended version of that1 presented during the seminar in April 2013 and aims to reevaluate certain points considered fundamental to the research conducted up to the moment on the highly significant collection of Italian painting from the 1920s/40s at MAC USP. First of all, we shall search to contextualize the relations between Italy and Brazil during the modernist period. Secondly, we will reassess the place Italian modern art occupied on the interna- tional scene between the wars and immediately after the World War II —when the collection in question was formed. Lastly, we will reconsider the works assem- bled by São Paulo’s first museum of modern art (which now belong to MAC USP). With this research we have taken up anew a front begun by the museum’s first director, Walter Zanini, who went on to publish the first systematic study on Brazilian art during the 1930s and 40s, in which he sought to draw out this relationship with the Italian artistic milieu. His book, published in 1993, came out at a time when Brazilian art historiography was in the middle of some important studies on modernism in Brazil and its relationship with the Italian artistic milieu, works such as Annateresa Fabris’ 1994 Futurismo Paulista, on how Futurism was received in Brazil, and Tadeu Chiarelli’s first articles on the relationship between the Italian Novecento and the São Paulo painters. -

Minerva Auctions

MINERVA AUCTIONS ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA MARTEDÌ 28 APRILE 2015 MINERVA AUCTIONS Palazzo Odescalchi Piazza SS. Apostoli 80 - 00187 Roma Tel: +39 06 679 1107 - Fax: +39 06 699 23 077 [email protected] www.minervaauctions.com FOLLOW US ON: Facebook Twitter Instagram LIBRI, AUTOGRAFI E STAMPE GIOIELLI, OROLOGI E ARGENTI Fabio Massimo Bertolo Andrea de Miglio Auction Manager & Capo Reparto Capo Reparto Silvia Ferrini Beatrice Pagani, Claudia Pozzati Office Manager & Esperto Amministratori DIPINTI E DISEGNI ANTICHI FOTOGRAFIA Valentina Ciancio Marica Rossetti Capo Reparto Specialist Adele Coggiola Junior Specialist & Amministratore Public Relations Muriel Marinuzzi Ronconi Amministrazione Viola Marzoli ARTE DEL XIX SECOLO Magazzino e spedizioni Claudio Vennarini Luca Santori Capo Reparto ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA Georgia Bava Capo Reparto Photo Stefano Compagnucci Silvia Possanza Layout Giovanni Morelli Amministratore Print CTS Grafica srl MINERVA AUCTIONS ROMA 111 ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA MARTEDÌ 28 APRILE 2015 ROMA, PALAZZO ODESCALCHI Piazza SS. Apostoli 80 PRIMA TORNATA - ORE 11 (LOTTI 1 - 169) SECONDA TORNATA - ORE 16 (LOTTI 170 - 349) ESPERTO / SPECIALIST Georgia Bava [email protected] REPARTO / DEPARTMENT Silvia Possanza [email protected] Per partecipare a questa asta online: www.liveauctioneers.com www.invaluable.com ESPOSIZIONE / VIEWING ROMA Da venerdì 24 a lunedì 27 aprile, ore 10.00 - 18.00 PREVIEW Per visionare i nostri cataloghi visitate il sito: ROMA www.minervaauctions.com Giovedì 23 aprile, ore 18.00 PRIMA TORNATA ORE 11 (LOTTI 1 - 169) Lotto 1 α 1 Jannis Kounellis (Pireo 1936) ROSA cartoncino sagomato e carta Japon nacrè, es.1/12, cm 76,5 x 57 Firma a matita in basso a sinistra Una piega al margine inferiore e tracce di umidità ai margini ed al verso. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process.