Catherine Ingrams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pages 4 Rotella, Lot 51 Pagine

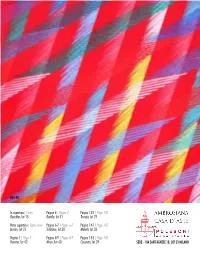

LOT 42 In copertina | Cover Pagine 4 | Pages 4 Pagina 133 | Page 133 Baechler, lot 15 Rotella, lot 51 Turcato, lot 29 Retro copertina | Back cover Pagine 6-7 | Pages 6-7 Pagina 142 | Page 142 Arman, lot 25 Schifano, lot 30 Melotti, lot 33 Pagina 1 | Page 1 Pagine 8-9 | Pages 8-9 Pagina 143 | Page 143 Dorazio, lot 42 Music, lot 60 Cassinari, lot 39 SEDE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18, 20123 MILANO ASTA ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 – presso LA POSTERIA 23 OTTOBRE - 4 NOVEMBRE, MILANO VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 0 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00 – ESCLUSO FESTIVI E 29 OTTOBRE) PREVIO APPUNTAMENTO 7-8-9 NOVEMBRE, MILANO, VIA SACCHI 7 (ORARIO 10.00-19.00) UNICA SESSIONE MARTEDÌ 10 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 16.00 LOTTI 1 - 243 PRESENTAZIONE TELEVISIVA TOP LOTS Lunedì 2/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Martedì 3/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Giovedì 5/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre Venerdì 6/11 ore 21.30-23 canale 134 del digitale terrestre OFFERTE SCRITTE FINO A LUNEDÌ 9 NOVEMBRE 2020 ORE 15.00 FAX +39 02 40703717 [email protected] È possibile partecipare in diretta on-line inscrivendosi (almeno 24 ore prima) sul nostro sito www.ambrosianacasadaste.com CONSULTAZIONE CATALOGO E MODULISTICA www.ambrosianacasadaste.com da venerdì 23 ottobre 2020 AMBROSIANA CASA D’ASTE / GALLERIA POLESCHI CASA D’ASTE - VIA SANT’AGNESE 18 20123 MILANO - TEL. +39 0289459708 - FAX +39 0240703717 www.ambrosianacasadaste.com • [email protected] LOT 51 338 1226703 5 MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART -

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

Aerial View and Its Role in Spatial Transformation: the Case of Istanbul a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Natural A

AERIAL VIEW AND ITS ROLE IN SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION: THE CASE OF ISTANBUL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY GÖKÇE ÖNAL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE IN ARCHITECTURE SEPTEMBER 2014 Approval of the thesis: AERIAL VIEW AND ITS ROLE IN SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION: THE CASE OF ISTANBUL submitted by GÖKÇE ÖNAL in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in Architecture Department, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Canan Özgen Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Güven Arif Sargın Head of Department, Architecture Inst. Dr. Mustafa Haluk Zelef Supervisor, Architecture Dept., METU Examining Committee Members: Prof. Dr. Belgin Turan Özkaya Architecture Dept., METU Inst. Dr. Mustafa Haluk Zelef Architecture Dept., METU Prof. Dr. Güven Arif Sargın Architecture Dept., METU Assoc. Dr. Namık Günay Erkal Architecture Dept., METU Inst. Dr. Davide Deriu Architecture Dept., University of Westminster Date: 04/09/2014 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Gökçe Önal Signature: iv ABSTRACT AERIAL VIEW AND ITS ROLE IN SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION: THE CASE OF ISTANBUL Önal, Gökçe M.Arch, Department of Architecture Supervisor: Inst. Dr. Mustafa Haluk Zelef September, 2014, 161 pages What is intended to be explored in this research is the historical course within which the transformation of aerial view has influenced the observation, documentation and realization of the built environment. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fillia's Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2r47405v Author Baranello, Adriana Marie Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fillia’s Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian By Adriana Marie Baranello 2014 © Copyright by Adriana Marie Baranello 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Fillia’s Futurism Writing, Politics, Gender and Art after the First World War By Adriana Marie Baranello Doctor of Philosophy in Italian University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Lucia Re, Co-Chair Professor Claudio Fogu, Co-Chair Fillia (Luigi Colombo, 1904-1936) is one of the most significant and intriguing protagonists of the Italian futurist avant-garde in the period between the two World Wars, though his body of work has yet to be considered in any depth. My dissertation uses a variety of critical methods (socio-political, historical, philological, narratological and feminist), along with the stylistic analysis and close reading of individual works, to study and assess the importance of Fillia’s literature, theater, art, political activism, and beyond. Far from being derivative and reactionary in form and content, as interwar futurism has often been characterized, Fillia’s works deploy subtler, but no less innovative forms of experimentation. For most of his brief but highly productive life, Fillia lived and worked in Turin, where in the early 1920s he came into contact with Antonio Gramsci and his factory councils. -

Aeropittura (Aeropainting) Watercolour, with Touches of Silver Pen, with Framing Lines in Green Ink, on Paper Laid Down Onto a Black Card (The Cover of a Notebook?)

Domenico (Mino) DELLE SITE (Lecce 1914 - Rome 1996) Aeropittura (Aeropainting) Watercolour, with touches of silver pen, with framing lines in green ink, on paper laid down onto a black card (the cover of a notebook?). Signed with monogram, inscribed and dated DSte FUTURISTA / 1932/ LF/ X in white gouache on the backing card, below the image. Titled AERO/ PITTURA on a separate sheet of paper cut out and pasted onto the lower right of the image. Further inscribed Delle Site Domenico / Alunno 4oCorso on the backing card. 93 x 103 mm. (3 5/8 x 4 1/8 in.) [image, at greatest dimensions]. 241 x 175 mm. (9 1/2 x 67/8 in.) [backing card] In September 1929 the Futurist theorist and founder Filippo Tomasso Marinetti published an article entitled ‘Perspectives of Flight and Aeropainting’ in the Gazzetta del Popolo in Turin, signed by Giacomo Balla, Fortunato Depero, Enrico Prampolini and several other Futurist painters. Republished in a revised and more complete version in 1931, the text served as a manifesto of the nascent branch of Futurism known as aeropittura, or Futurist aeropainting: ‘We Futurists declare that: 1. The changing perspectives of flight are an absolutely new reality that has nothing to do with the traditional reality of terrestrial perspectives. 2. The elements of this new reality have no fixed point and are built out of the same perennial mobility. 3. The painter cannot observe and paint unless he experiences the same speed as these elements. 4. Painting this new reality from the air imposes a profound contempt for detail and a need to summarize and transfigure everything…7. -

Futurism's Photography

Futurism’s Photography: From fotodinamismo to fotomontaggio Sarah Carey University of California, Los Angeles The critical discourse on photography and Italian Futurism has proven to be very limited in its scope. Giovanni Lista, one of the few critics to adequately analyze the topic, has produced several works of note: Futurismo e fotografia (1979), I futuristi e la fotografia (1985), Cinema e foto- grafia futurista (2001), Futurism & Photography (2001), and most recently Il futurismo nella fotografia (2009).1 What is striking about these titles, however, is that only one actually refers to “Futurist photography” — or “fotografia futurista.” In fact, given the other (though few) scholarly studies of Futurism and photography, there seems to have been some hesitancy to qualify it as such (with some exceptions).2 So, why has there been this sense of distacco? And why only now might we only really be able to conceive of it as its own genre? This unusual trend in scholarly discourse, it seems, mimics closely Futurism’s own rocky relationship with photography, which ranged from an initial outright distrust to a later, rather cautious acceptance that only came about on account of one critical stipulation: that Futurist photography was neither an art nor a formal and autonomous aesthetic category — it was, instead, an ideological weapon. The Futurists were only able to utilize photography towards this end, and only with the further qualification that only certain photographic forms would be acceptable for this purpose: the portrait and photo-montage. It is, in fact, the very legacy of Futurism’s appropriation of these sub-genres that allows us to begin to think critically about Futurist photography per se. -

ACTION | ABSTRACTION Alberto Burri Lucio Fontana

ACTION | ABSTRACTION Alberto Burri Lucio Fontana PRESS RELEASE 14th January 2019 TORNABUONI ART LONDON - 46 Albemarle St, W1S 4JN London Exhibition: 8th February - 30th March 2019 Press view: 10am - 12pm from 6th to 8th February Conference: 7th March, 5pm-7pm, Royal Academy of Arts London, ‘Alberto Burri: A Radical Legacy’ moderated by Tim Marlow, Director of Programmes at the Royal Academy, with professor Bruno Corà, President of the Alberto Burri Foundation, professor Luca Massimo Barbero, Director of the Art History Institute at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, and professor Bernard Blistène, Director of the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. This exhibition sets out to recapture one of the most dramatic periods of Post-War art in Italy. The selection of works by the avant-garde artists Alberto Burri and Lucio Fontana will shed light on how the trauma and destruction of two world wars spurred these artists to reject representation and to return to primordial forms of communication through material and gesture – in Fontana’s case, through a simple but supremely efective piercing of the canvas surface and, in Burri’s case, a radical and sometimes violent reimagining of the expressive potential of traditionally ‘non-artistic’ materials. The show will shine a light on the correspondences and convergences between these artists who, despite their vastly difering aesthetics, now stand together as luminaries of material- based abstraction and an inspiration to an entire generation of artists who grew up in their shadow. Tornabuoni Art will explore their work in a tightly curated selection of highlights on display in the London gallery. Both artists are being honoured with institutional exhibitions this year. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Carla Accardi Biography

SPERONE WESTWATER 257 Bowery New York 10002 T + 1 212 999 7337 F + 1 212 999 7338 www.speronewestwater.com Carla Accardi Biography 1924 Born Trapani, Sicily 2014 Died Rome, Italy One Person Exhibitions: 1950 “Carla Accardi. 15 Tempere,” Galleria Age d’Or, Rome, 16 November – 1 December 1951 “Accardi e Sanfilippo,” Libreria Salto, Milan, 31 March – 6 April (catalogue) 1952 “Carla Accardi,” Galleria Ill Pincio, Rome (catalogue) “Mostra personale della pittrice Carla Accardi,” Galleria d’Arte Contemporanea, Florence (catalogue) “Carla Accardi-Antonio Sanfilippo,” Galleria Il Cavallino, Venice, 5 – 23 July (catalogue) 1955 “Accardi,” Galleria San Marco, Rome, 16 – 30 June 1956 “Peintures de Accardi - Sculptures de Delahaye,” Galerie Stadler, Paris, 18 February – 8 March (catalogue) 1957 “Accardi,” Galleria Dell’Ariete, Milan (catalogue) 1958 “Carla Accardi,” Galleria La Salita, Rome “Carla Accardi. Peintures récentes,” Galeria L’Entracte, Lausanne, Switzerland 1959 “Dipinti e tempere di Carla Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin (catalogue) “Accardi. Opere recenti,” Galleria La Salita, Rome 1960 “Dipinti di Carla Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin (catalogue) 1961 “Carla Accardi,”Galleria La Salita, Rome “Carla Accardi,” Parma Gallery, New York, 23 May – 10 June “Carla Accardi: Recent Paintings,” New Vision Centre, London, 5 – 24 June 1964 “Italian Pavilion – Solo Room, ” curated by Carla Lonzi, XXXII Biennale di Venezia, Venice, 20 July – 18 October (catalogue) “Accardi,” Galleria Notizie, Turin, 16 October – 15 November (catalogue) 1965 Galleria -

Minerva Auctions

MINERVA AUCTIONS ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA MARTEDÌ 28 APRILE 2015 MINERVA AUCTIONS Palazzo Odescalchi Piazza SS. Apostoli 80 - 00187 Roma Tel: +39 06 679 1107 - Fax: +39 06 699 23 077 [email protected] www.minervaauctions.com FOLLOW US ON: Facebook Twitter Instagram LIBRI, AUTOGRAFI E STAMPE GIOIELLI, OROLOGI E ARGENTI Fabio Massimo Bertolo Andrea de Miglio Auction Manager & Capo Reparto Capo Reparto Silvia Ferrini Beatrice Pagani, Claudia Pozzati Office Manager & Esperto Amministratori DIPINTI E DISEGNI ANTICHI FOTOGRAFIA Valentina Ciancio Marica Rossetti Capo Reparto Specialist Adele Coggiola Junior Specialist & Amministratore Public Relations Muriel Marinuzzi Ronconi Amministrazione Viola Marzoli ARTE DEL XIX SECOLO Magazzino e spedizioni Claudio Vennarini Luca Santori Capo Reparto ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA Georgia Bava Capo Reparto Photo Stefano Compagnucci Silvia Possanza Layout Giovanni Morelli Amministratore Print CTS Grafica srl MINERVA AUCTIONS ROMA 111 ARTE MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA MARTEDÌ 28 APRILE 2015 ROMA, PALAZZO ODESCALCHI Piazza SS. Apostoli 80 PRIMA TORNATA - ORE 11 (LOTTI 1 - 169) SECONDA TORNATA - ORE 16 (LOTTI 170 - 349) ESPERTO / SPECIALIST Georgia Bava [email protected] REPARTO / DEPARTMENT Silvia Possanza [email protected] Per partecipare a questa asta online: www.liveauctioneers.com www.invaluable.com ESPOSIZIONE / VIEWING ROMA Da venerdì 24 a lunedì 27 aprile, ore 10.00 - 18.00 PREVIEW Per visionare i nostri cataloghi visitate il sito: ROMA www.minervaauctions.com Giovedì 23 aprile, ore 18.00 PRIMA TORNATA ORE 11 (LOTTI 1 - 169) Lotto 1 α 1 Jannis Kounellis (Pireo 1936) ROSA cartoncino sagomato e carta Japon nacrè, es.1/12, cm 76,5 x 57 Firma a matita in basso a sinistra Una piega al margine inferiore e tracce di umidità ai margini ed al verso. -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 the Continent That the EU Does Not Know

Art in Europe 1945 Art in — 1968 The Continent EU Does that the Not Know 1968 The The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 Supplement to the exhibition catalogue Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Phase 1: Phase 2: Phase 3: Trauma and Remembrance Abstraction The Crisis of Easel Painting Trauma and Remembrance Art Informel and Tachism – Material Painting – 33 Gestures of Abstraction The Painting as an Object 43 49 The Cold War 39 Arte Povera as an Artistic Guerilla Tactic 53 Phase 6: Phase 7: Phase 8: New Visions and Tendencies New Forms of Interactivity Action Art Kinetic, Optical, and Light Art – The Audience as Performer The Artist as Performer The Reality of Movement, 101 105 the Viewer, and Light 73 New Visions 81 Neo-Constructivism 85 New Tendencies 89 Cybernetics and Computer Art – From Design to Programming 94 Visionary Architecture 97 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Introduction Praga Magica PETER WEIBEL MICHAEL BIELICKY 5 29 Phase 4: Phase 5: The Destruction of the From Representation Means of Representation to Reality The Destruction of the Means Nouveau Réalisme – of Representation A Dialog with the Real Things 57 61 Pop Art in the East and West 68 Phase 9: Phase 10: Conceptual Art Media Art The Concept of Image as From Space-based Concept Script to Time-based Imagery 115 121 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know ZKM_Atria 1+2 October 22, 2016 – January 29, 2017 4 At the initiative of the State Museum Exhibition Introduction Center ROSIZO and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, the institutions of the Center for Fine Arts Brussels (BOZAR), the Pushkin Museum, and ROSIZIO planned and organized the major exhibition Art in Europe 1945–1968 in collaboration with the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe.