Pay to Play, Residential Development Fees in California, 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

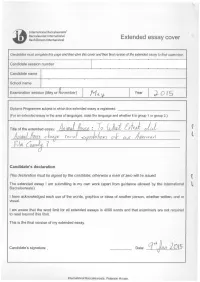

This Cover and Their Final Version Extended

then this cover and their final version extended and whether it is group 1 or Peterson :_:::_.,·. ,_,_::_ ·:. -. \")_>(-_>·...·,: . .>:_'_::°::· ··:_-'./·' . /_:: :·.·· . =)\_./'-.:":_ .... -- __ · ·, . ', . .·· . Stlpervisot1s t~pe>rt ~fld declaration J:h; s3pervi;o(,r;u~f dompietethisreport,. .1ign .the (leclaratton andtfien iiv~.ihe pna:1 ·tersion·...· ofth€7 essay; with this coyerattachedt to the Diploma Programme coordinator. .. .. .. ::,._,<_--\:-.·/·... ":";":":--.-.. ·. ---- .. ,>'. ·.:,:.--: <>=·. ;:_ . .._-,..-_,- -::,· ..:. 0 >>i:mi~ ~;!~;:91'.t~~~1TAt1.tte~) c P1~,§.~p,rmmeht, ;J} a:,ir:lrapriate, on the candidate's perforrnance, .111e. 9q1Jtext ·;n •.w111ctrth~ ..cahdtdatei:m ·.. thft; J'e:~e,~rch.·forf fle ...~X: tendfKI essay, anydifflcu/ties ef1COUntered anq ftCJW thes~\WfJ(fj ()VfJfCOfflf! ·(see .· •tl1i! ext~nciede.ssay guide). The .cpncl(ldipg interview .(vive . vope) ,mt;}y P.fOvidtli .US$ftJf .informf.ltion: pom1r1~nt~ .can .flelp the ex:amr1er award.a ··tevetfot criterion K.th9lisJtcjudgrpentJ. po not. .comment ~pverse personal circumstan9~s that•· m$iiybave . aff.ected the candidate.\lftl'1e cr.rrtotJnt ottime.spiimt qa;ndidate w~s zero, Jt04 must.explain tf1is, fn particular holft!1t was fhf;Jn ppssible .to ;;1.uthentic;at? the essa~ canciidaJe'sown work. You rnay a-ttachan .aclditfonal sherJtJf th.ere isinspfffpi*?nt f pr1ce here,·.···· · Overall, I think this paper is overambitious in its scope for the page length / allowed. I ~elieve it requires furt_her_ editing, as the "making of" portion takes up too ~ large a portion of the essay leaving inadequate page space for reflections on theory and social relevance. The section on the male gaze or the section on race relations in comedy could have served as complete paper topics on their own (although I do appreciate that they are there). -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

2019 National Sports and Entertainment History Bee Round 2

Sports and Entertainment Bee 2018-2019 Prelims 2 Prelims 2 Regulation (Tossup 1) This man stars in an oft-parodied commercial in which he states \Ballgame" before taking a drink of Gatorade Flow. In 2017, this man's newly acquired teammate told him \they say I gotta come off the bench." This man missed nearly the entire 2014-2015 season after suffering a horrific leg injury while practicing for the US National Team. Sam Presti sent Domantas Sabonis and Victor Oladipo to the Indiana Pacers in exchange for this player, who then surprisingly didn't bolt to the Lakers in the 2018 off-season. For the point, name this player who formed an unsuccessful \Big Three" with Carmelo Anthony and Russell Westbrook on the Oklahoma City Thunder. ANSWER: Paul Clifton Anthony George (accept PG13) (Tossup 2) This series used Ratatat's \Cream on Chrome" as background music for many early episodes. Side projects of this series include a \Bedtime" version featuring literature readings and an educational \Basics" version. This series' 2019 April Fools' Day gag involved the a 4Kids dub of Pokemon claiming that Brock loved jelly donuts. This series celebrated million-subscriber benchmarks with episodes featuring the Taco Town 15-layer taco and the Every-Meat Burrito and Death Sandwich from Regular Show. For the point, name this YouTube channel starring Andrew Rea, who cooks various foods as inspired by popular culture. ANSWER: Binging with Babish (Tossup 3) The creators of this game recently announced a \Royal" edition which will add a third semester of gameplay. In April 2019, a heavily criticzed Kotaku article claimed that this game's theme song, \Wake up, Get up, Get out there," contains a slur against people with learning disabilities. -

New Years Eve Films

Movies to Watch on New Year's Eve Going Out Is So Overrated! This year, New Year’s Eve celebrations will have to be done slightly differently due to the pandemic. So, the Learning Curve thought ‘Why not just ring in 2021 with some feel-good movies in your comfy PJs instead?’ After all, everyone knows that the best way to turn over a new year is snuggled up in front of the TV with a hot beverage in your hand. The good news is, no matter how you want to feel going into the next year, there’s a movie on this list that’ll deliver. Best of all — you won’t wake up the next day and begin January with a hangover! Godfather Part II (1974) Director: Francis Ford Coppola Starring: Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Robert Duvall Continuing the saga of the Corleone crime family, the son, Michael (Pacino) is trying to expand the business to Las Vegas, Hollywood and Cuba. They delve into double crossing, greed and murder as they all try to be the most powerful crime family of all time. Godfather part II is hailed by fans as a masterpiece, a great continuation to the story and the best gangster movie of all time. This is a character driven movie, as we see peoples’ motivations, becoming laser focused on what they want and what they will do to get it. Although the movie is a gripping slow crime drama, it does have one flaw, and that is the length of the movie clocking in at 3 hours and 22 minutes. -

National Lampoon's Animal House

From: Reviews and Criticism of Vietnam War Theatrical and Television Dramas (http://www.lasalle.edu/library/vietnam/FilmIndex/home.htm) compiled by John K. McAskill, La Salle University ([email protected]) N2825 NATIONAL LAMPOON’S ANIMAL HOUSE (USA, 1978) (Other titles: American college; Animal house) Credits: director, John Landis ; writers, Harold Ramis, Douglas Kenney, Chris Miller. Cast: John Belushi, Tim Matheson, John Vernon, Thomas Hulce. Summary: Comedy film set at a 1960s Middle Western college. The members of Delta Tau Chi fraternity offend the straight-arrow and up-tight people on campus in a film which irreverently mocks college traditions. One of the villains is an ROTC cadet who, it is noted at the end of the film, was later shot by his own men in Vietnam. Ansen, David. “Movies: Gross out” Newsweek 92 (Aug 7, 1978), p. 85. Barbour, John. [National Lampoon’s animal house] Los Angeles 23 (Sep 1978), p. 240-43. Bartholomew, David. “National Lampoon’s animal house” Film bulletin 47 (Oct/Nov 1978), p. R-F. Biskind, Peter. [National Lampoon’s animal house] Seven days 2/17 (Nov 10, 1978), p. 33. Bookbinder, Robert. The films of the seventies Secaucus, N.J. : Citadel, 1982. (p. 225-28) Braun, Eric. “National Lampoon’s animal house” Films and filming 25/7 (Apr 1979), p. 31-2. Canby, Vincent. “What’s so funny about potheads and toga parties?” New York times 128 (Nov 19, 1978), sec. 2, p. 17. Cook, David A.. Lost illusions : American cinema in the shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970-1979 New York : Scribner’s, 1999. -

Housing Policy Debate Tracking and Explaining Neighborhood

This article was downloaded by: [University of Pennsylvania], [John D. Landis] On: 18 May 2015, At: 08:30 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Housing Policy Debate Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rhpd20 Tracking and Explaining Neighborhood Socioeconomic Change in U.S. Metropolitan Areas Between 1990 and 2010 John D. Landisa a Department of City and Regional Planning, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA Published online: 18 May 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: John D. Landis (2015): Tracking and Explaining Neighborhood Socioeconomic Change in U.S. Metropolitan Areas Between 1990 and 2010, Housing Policy Debate, DOI: 10.1080/10511482.2014.993677 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2014.993677 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Canadianization of the American Media Landscape Eric Weeks

Document generated on 09/26/2021 3:27 a.m. International Journal of Canadian Studies Revue internationale d’études canadiennes Where is There? The Canadianization of the American Media Landscape Eric Weeks Culture — Natures in Canada Article abstract Culture — natures au Canada An increasing number of American film and television productions are filmed Number 39-40, 2009 inCanada. This paper argues that while the Canadianization of the American medialandscape may make financial sense, the trend actually causes harm to URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/040824ar the culturallandscape of both countries. This study examines reasons DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/040824ar contributing to thetendency to move production to Canada and how recent events have impactedHollywood's northern migration. Further, "authentic" representations of place onthe big and small screens are explored, as are the See table of contents effects that economic runawayproductions—those films and television programs that relocate production due tolower costs found elsewhere—have on a national cultural identity and audiencereception, American and Canadian Publisher(s) alike. Conseil international d'études canadiennes ISSN 1180-3991 (print) 1923-5291 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Weeks, E. (2009). Where is There? The Canadianization of the American Media Landscape. International Journal of Canadian Studies / Revue internationale d’études canadiennes, (39-40), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.7202/040824ar Tous droits réservés © Conseil international d'études canadiennes, 2009 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Best Movies in Every Genre

Best Movies in Every Genre WTOP Film Critic Jason Fraley Action 25. The Fast and the Furious (2001) - Rob Cohen 24. Drive (2011) - Nichols Winding Refn 23. Predator (1987) - John McTiernan 22. First Blood (1982) - Ted Kotcheff 21. Armageddon (1998) - Michael Bay 20. The Avengers (2012) - Joss Whedon 19. Spider-Man (2002) – Sam Raimi 18. Batman (1989) - Tim Burton 17. Enter the Dragon (1973) - Robert Clouse 16. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) – Ang Lee 15. Inception (2010) - Christopher Nolan 14. Lethal Weapon (1987) – Richard Donner 13. Yojimbo (1961) - Akira Kurosawa 12. Superman (1978) - Richard Donner 11. Wonder Woman (2017) - Patty Jenkins 10. Black Panther (2018) - Ryan Coogler 9. Mad Max (1979-2014) - George Miller 8. Top Gun (1986) - Tony Scott 7. Mission: Impossible (1996) - Brian DePalma 6. The Bourne Trilogy (2002-2007) - Paul Greengrass 5. Goldfinger (1964) - Guy Hamilton 4. The Terminator (1984-1991) - James Cameron 3. The Dark Knight (2008) - Christopher Nolan 2. The Matrix (1999) - The Wachowskis 1. Die Hard (1988) - John McTiernan Adventure 25. The Goonies (1985) - Richard Donner 24. Gunga Din (1939) - George Stevens 23. Road to Morocco (1942) - David Butler 22. The Poseidon Adventure (1972) - Ronald Neame 21. Fitzcarraldo (1982) - Werner Herzog 20. Cast Away (2000) - Robert Zemeckis 19. Life of Pi (2012) - Ang Lee 18. The Revenant (2015) - Alejandro G. Inarritu 17. Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972) - Werner Herzog 16. Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) - Frank Lloyd 15. Pirates of the Caribbean (2003) - Gore Verbinski 14. The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) - Michael Curtiz 13. The African Queen (1951) - John Huston 12. To Have and Have Not (1944) - Howard Hawks 11. -

Developing Policy from the Ground Up: Examining Entitlement in the Bay Area to Inform California's Housing Policy Debates

1_BIBER_FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 11/21/2018 10:48 AM Developing Policy from the Ground Up: Examining Entitlement in the Bay Area to Inform California’s Housing Policy Debates Moira O’Neill,1 Giulia Gualco-Nelson,2 and Eric Biber3 *Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the Silicon Valley Community Foundation for providing funding support for this research, and acknowledge the support of a team of talented students that assisted with research, including: Terry Chau, Madison Delaney, Shreya Ghoshal, Madeline Green, Megan Grosspietsch, Grace Jang, Heather Jones, Claire Kostohryz, Rachel Kramer, Erin Lapeyrolerie, Adrian Napolitano, Maxwell Radin, Raine Robichaud, Colette Rosenberg, Alicia Sidik, Nathan Theobald, Helen Veazey, Dulce Walton Molina, Kenneth Warner, Dean Wyrzykowski, and Luke Zhang. Thanks to Chris Elmendorf for helpful comments. Human Subjects Statement: The Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research at University of California at Berkeley reviewed and approved all research protocols. 1. Senior Research Fellow, Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment, Berkeley Law and Associate Research Scientist in Law & City Planning, Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California, Berkeley; Adjunct Assistant Professor and Associate Research Scholar, Urban Community and Health Equity Lab, Columbia University. 2. Associate Research Scholar, Urban Community and Health Equity Lab, Columbia University; Affiliate, Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment, BerkeleyLaw, University of California, Berkeley. 3. Professor of Law, BerkeleyLaw, University of California, Berkeley. 1 1_BIBER_FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 11/21/2018 10:48 AM Hastings Environmental Law Journal, Vol. 25, No. 1, Winter 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 5 PART I: BACKGROUND .......................................................................... 7 A. -

The Grand Budapest Hotel

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: “THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL,” “GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY” and “AMERICAN HORROR STORY: FREAK SHOW” Among Make-Up Artists Winners at the Make-Up Artists & Hair Stylists Guild Awards “BIRDMAN,” “DOWNTON ABBEY” and “DANCING WITH THE STARS” Among Hair Stylists Winners GUILLERMO DEL TORO RECEIVES DISTINGUISHED ARTISAN AWARD FROM GOLDEN GLOBE®-WINNER RON PERLMAN ***PLEASE GO TO HTTP://WWW.IMAGE.NET/MUAHS2015 TO ACCESS WINNER INFO, PHOTOS AND VIDEO FOOTAGE FROM THE EVENT*** LOS ANGELES, Feb. 14, 2015 – The Make-Up Artists & Hair Stylists Guild (MUAHS, IATSE Local 706) tonight announced winners of its Annual Make-Up Artists & Hair Stylists Guild Awards in 19 categories of film, television, commercials and live theater during the black-tie ceremony at the Paramount Studios Theatre. The awards took place before an audience of more than 500, including guild members, industry executives and press. MUAHS President Sue Cabral-Ebert presided over the awards ceremony with Wendi McLendon-Covey (The Goldbergs) serving as host. The MUAHS Awards after-party was courtesy of M.A.C. Cosmetics and spirits were presented by Patrón Tequila. Golden Globe®-winner Ron Perlman (Sons of Anarchy) presented the Distinguished Artisan Award to his longtime friend and collaborator Guillermo Del Toro (Crimson Peak). Acclaimed director John Landis presented the Make-Up Artist Lifetime Achievement Award to Oscar®- winning make-up legend Rick Baker. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) President Cheryl Boone Isaacs presented the Hair Stylist Lifetime Achievement Award to Emmy® Award-winning hair stylist Kathryn Blondell. Presenters for this year’s awards included Alfre Woodard (State of Affairs), Sarah Paulson and Jamie Brewer (American Horror Story: Freak Show), Darby Stanchfield (Scandal), Tony Revolori (The Grand Budapest Hotel), Ethan Embry (Grace and Frankie), Raymond Cruz (Better Call Saul), Amy Landecker (Transparent), Beau Garrett (Girlfriends’ Guide to Divorce) and Jillian Rose Reed (Awkward). -

In Re Beds & Bars Limited

THIS OPINION IS A PRECEDENT OF THE TTAB Mailed: May 5, 2017 UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE _____ Trademark Trial and Appeal Board _____ In re Beds & Bars Limited _____ Serial No. 85597669 _____ Michael E. Hall and Mark B. Harrison of Venable LLP, for Beds & Bars Limited. Ronald L. Fairbanks, Trademark Examining Attorney, Law Office 119, Brett J. Golden, Managing Attorney. _____ Before Quinn, Adlin and Masiello, Administrative Trademark Judges. Opinion by Quinn, Administrative Trademark Judge: Beds & Bars Limited (hereinafter “Applicant”) seeks registration on the Principal Register of the mark BELUSHI’S (in standard character format) for travel reservation, escorting of travellers, car parking, courier services, arranging and providing transportation for travellers, sightseeing, information services regarding travel (in International Class 39); and hotel, hostel, public houses, restaurant and catering services, reservation of temporary accommodation, Serial No. 85597669 boarding houses, cocktail lounges and coffee bars (in International Class 43).1 The Trademark Examining Attorney refused registration of Applicant’s mark pursuant to Section 2(e)(4) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(4), on the ground that the applied-for mark is primarily merely a surname. When the refusal was made final, Applicant appealed and requested reconsideration. The Examining Attorney denied the request for reconsideration but failed to address Applicant’s alternative amendment to the Supplemental Register. Applicant then filed a request for remand. After the Examining Attorney accepted this alternative amendment, the appeal was resumed on the sole issue of whether Applicant’s mark BELUSHI’S is registrable on the Principal Register. By way of additional background, the Examining Attorney, in the first Office Action dated August 8, 2012, raised two refusals, namely, the surname refusal and a refusal under Section 2(a) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C.