Innovating Authentically: Cultural Differentiation in the Animation Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Malaysian Cartoon Animation

THE EVOLUTION OF MALAYSIAN CARTOON ANIMATION Faryna Mohd Khalis Normah Mustaffa Mohd Nor Shahizan Ali Neesa Ameera Mohamed Salim [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT A cartoon can be defined as an unrealistic style of sketching and or funny figures that can make people laugh. Aside from entertainment purposes, cartoons are also used to send messages without a serious tone and indirectly telling something sarcastically. In April 2019, Malaysia was shocked by the headline that ‘Doraemon’ had been selected to represent the Japanese themed cartoon exhibition in conjunction with Visit Malaysia 2020. Malaysian art activists, specifically those who has a cartoon animation background, were very upset and expressed their dissatisfaction with the news. Local legendary cartoonist Datuk Lat also showed his disappointment and made a stand that a local cartoon character should have been chosen to represent Malaysia. Therefore, this research aims to illustrate the development of Malaysian cartoons from when they first started in newspapers, until their existence today in the form of animation on digital platforms. In sequence, Malaysia produced cartoons in newspapers, magazines, blogs, television and cinema, whereby this is in parallel with the development of technology. From hand- drawn art for ‘Usop Sontorian’ to digital animation for the film ‘Upin dan Ipin’, Malaysians should be more appreciative and proud of our local cartoons rather than those from other countries. Keywords: Local identity, Characteristic, Animation, Comic, Character design. Introduction Cartoons are fundamentally known as entertainment for kids. But due to cultural values, technological development and education, our cliché perception has changed to that cartoons are actually a source of effective communication for all ages (Muliyadi, 2001, 2010, 2015). -

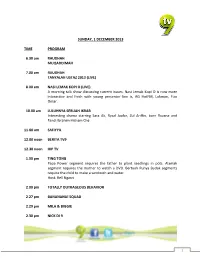

1 SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 Am

SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 am RAUDHAH MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am RAUDHAH TANYALAH USTAZ 2013 (LIVE) 8.00 am NASI LEMAK KOPI O (LIVE) A morning talk show discussing current issues. Nasi Lemak Kopi O is now more interactive and fresh with young presenter line is, AG HotFM, Lokman, Fizo Omar. 10.00 am LULUHNYA SEBUAH IKRAR Interesting drama starring Sara Ali, Ryzal Jaafar, Zul Ariffin, born Ruzana and Fandi Ibrahim Hisham Che 11.00 am SAFIYYA 12.00 noon BERITA TV9 12.30 noon HIP TV 1.00 pm TING TONG Papa Power segment requires the father to plant seedlings in pots. Alamak segment requires the mother to watch a DVD. Bertuah Punya Budak segments require the child to make a sandwich and water. Host: Bell Ngasri 2.00 pm TOTALLY OUTRAGEOUS BEHAVIOR 2.27 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 2.29 pm MILA & BIGGIE 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 1 TEAM UMIZOOMI 3.00 pm NICK DI 9 DORA THE EXPLORER 3.30 pm NICK DI 9 ADVENTURES OF JIMMY NEUTRONS 4.00 pm NICK DI 9 PLANET SHEEN 4.30 pm NICK DI 9 AVATAR THE LEGEND OF AANG 5.00 pm NICK DI 9 SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 5.28 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 5.30 pm BOLA KAMPUNG THE MOVIE Amanda is a princess who comes from the virtual world of a game called "Kingdom Hill '. She was sent to the village to find Pewira Suria, the savior who can end the current crisis. Cast: Harris Alif, Aizat Amdan, Harun Salim Bachik, Steve Bone, Ezlynn 7.30 pm SWITCH OFF 2 The Award Winning game show returns with a new twist! Hosted by Rockstar, Radhi OAG, and the game challenges bands with a mission to save their band members from the Mysterious House in the Woods. -

1 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2012 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 Am

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2012 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 am MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am TANYALAH USTAZ Each episode features an Ustaz to answer all the questions via email or phone call based on the verses of Quran. 8.00 am NASI LEMAK KOPI O A morning talk show programme discussing current and interesting issues. Hosts: Aziz Desa, Abu Talib Husin, Syarifah Nur Syed Ali, Farrah Adeeba, Sharifah Shahirah, Ashraf Muslim, AG Hotfm and Farah Anuar. 10.00 am DENDAM ORANG MINYAK A terrific drama series for the whole family. Casts: Azhan Rani, Latiff Borgiba, Kuza, Aqasha dan Melissa Mauren 11.00 am SUKU (R) 11.30 am REMAJA 2011 (R) 12.00 pm BERITA TV9 12.30 pm SKRIN HUJUNG MINGGU BAKAR BACKHOE 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 WONDERPETS Linny the guinea pig, Tuck the turtle, and Ming-Ming the duckling are class pets in a schoolhouse. When they are left alone in the classroom after each school day ends, they wait for a special phone. 3.00 pm NICK DI 9 GO, DIEGO, GO!. 3.30 pm NICK DI 9 DORA, THE EXPLORER 4.00 pm NICK DI 9 HEY ARNOLD 1 4.30 pm NICK DI 9 THE ADVENTURES OF JIMMY NEUTRON 5.00 pm NICK DI 9 SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 5.28 pm BERITA ADIK Berita Adik is a new program for children on TV9. It will provide the latest information and useful info to the child and family about what is happening and being talked. Hosted by Dayana (Small Idol second season winner), Fimie (Best Child Actor) and Afiq (Actor role in Mahathir's Che Det The Musical). -

Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings

Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA: PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS EDISI KEDUA TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA: PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS EDISI KEDUA Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Kuala Lumpur 2020 © Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia 2020 Hak cipta terpelihara. Tiada bahagian terbitan ini boleh diterbitkan semula atau ditukar dalam apa jua bentuk dan dengan apa jua sama ada elektronik, mekanikal, fotokopi, rakaman dan sebagainya sebelum mendapat kebenaran bertulis daripada Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. Diterbitkan oleh: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia 232, Jalan Tun Razak 50572 Kuala Lumpur Tel: 03-2687 1700 Faks: 03-2694 2490 www.pnm.gov.my www.facebook.com/PerpustakaanNegaraMalaysia blogpnm.pnm.gov.my twitter.com/PNM_sosial Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Data Pengkatalogan-dalam-Penerbitan TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA : PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS. – EDISI KEDUA. Mode of access: Internet eISBN 978-967-931-359-8 1. Subject headings--Malaysia. 2. Subject headings, Malay. 3. Government publications--Malaysia. 4. Electronic books. I. Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. 025.47 KANDUNGAN Sekapur Sirih Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia i Prakata Pengenalan ii Objektif iii Format iv-v Skop vi-viii Senarai Ahli Jawatankuasa Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings ix Senarai Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Tajuk Perkara Topikal (Tag 650) 1-152 Tajuk Perkara Geografik (Tag 651) 153-181 Bibliografi 183-188 Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Sekapur Sirih Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Syukur Alhamdulillah dipanjatkan dengan penuh kesyukuran kerana dengan izin- Nya Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia telah berjaya menerbitkan buku Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Edisi Kedua ini. -

PDF ATF Dec12

> 2 < PRENSARIO INTERNATIONAL Commentary THE NEW DIMENSIONS OF ASIA We are really pleased about this ATF issue of world with the dynamics they have for Asian local Prensario, as this is the first time we include so projects. More collaboration deals, co-productions many (and so interesting) local reports and main and win-win business relationships are needed, with broadcaster interviews to show the new stages that companies from the West… buying and selling. With content business is taking in Asia. Our feedback in this, plus the strength and the capabilities of the the region is going upper and upper, and we are region, the future will be brilliant for sure. pleased about that, too. Please read (if you can) our central report. There THE BASICS you have new and different twists of business devel- For those reading Prensario International opments in Asia, within the region and below the for the first time… we are a print publication with interaction with the world. We stress that Asia is more than 20 years in the media industry, covering Prensario today one of the best regions of the world to proceed the whole international market. We’ve been focused International with content business today, considering the size of on Asian matters for at least 15 years, and we’ve been ©2012 EDITORIAL PRENSARIO SRL PAYMENTS TO THE ORDER OF the market and the vanguard media ventures we see attending ATF in Singapore for the last 5 years. EDITORIAL PRENSARIO SRL in its main territories; the problems of the U.S. and As well, we’ve strongly developed our online OR BY CREDIT CARD. -

THURSDAY, AUGUST 1, 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.00 Am AL QURAN MENJAWAB BERSAMA DR DANIAL ZAINAL ABIDIN

THURSDAY, AUGUST 1, 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.00 am AL QURAN MENJAWAB BERSAMA DR DANIAL ZAINAL ABIDIN (RR) 6.30 am MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am TANYALAH USTAZ 2013: RAMADAN SPECIAL Each episode will feature an Ustaz to answer all the questions via email or phone call based on the verses of Quran. 8.00 am PESAN ATOK (R) 8.30 am UPIN & IPIN 9.00 pg SAFIYYA (R) 10.00 pg PASUKAN GERAKAN MARIN 3 (R) 11.00 pg MARHABBA DE LAILA (R) 12.00 pm BERITA TV9 12.30 pm DRAMA INDONESIA - LAGU CINTA NIRMALA A gripping sinetron for all to watch! Casts: Nabila Syakieb, Samuel Zylgwyn, Giovanni Yosafat Tobing, Dhini Aminarti, Sheila Marcia Joseph. 1.30 pm BABY LOONEY TUNES Baby Looney Tunes is an American animated television series that shows Looney Tunes characters as babies till toddlers. 2.00 pm SUPERMAN THE ANIMATED SERIES Batman Beyond tells the story of a new and different Batman. It takes place far in the future, years after Batman appeared for the last time. Terry McGinnis rekindles the fire in Bruce Wayne's bitter old heart, and takes up the role as the new Dark Knight - with the old one as his mentor. 2.28 pm BANANANA! SQUAD A capsule talk show hosted by 2 bubbly kids, who are sharing the ideas of what’s hot, fun in the kids world, with injection of general knowledge. Host: Hadi and Deera 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 WONDERPETS Linny the guinea pig, Tuck the turtle, and Ming-Ming the duckling are class pets in a schoolhouse. -

10 FRANCSS 10 Francs, 28 Rue De L'equerre, Paris, France 75019 France, Tel: + 33 1 487 44 377 Fax: + 33 1 487 48 265

MIPTV - MIPDOC 2013 PRE-MARKET UNABRIDGED COMPREHENSIVE PRODUCT GUIDE SPONSORED BY: NU IMAGE – MILLENNIUM FILMS SINCE 1998 10 FRANCSS 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, France 75019 France, Tel: + 33 1 487 44 377 Fax: + 33 1 487 48 265. www.10francs.fr, [email protected] Distributor At MIPTV: Christelle Quillévéré (Sales executive) Market Stand: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + 33 6 628 04 377 Fax: + 33 1 487 48 265 COLORS OF MATH Science, Education (60') Language: English Russian, German, Finnish, Swedish Director: Ekaterina Erementp Producer: EE Films Year of Production: 2011 To most people math appears abstract, mysterious, complicated, inaccessible. But math is nothing but another language to express the world. Math can be sensual. Math can be tasted, it smells, it creates sound and color. One can touch it - and be touched by it... Incredible Casting : Cedric Villani (french - he talks about « Taste »). Anatoly Fomenko (russian - he talks about « Sight »), Aaditya V. Rangan (american - he talks about « Smell »), Gunther Ziegler (german - he talks about « To touch » and « Geométry »), Jean- Michel Bismut (french - he talks about « Sound » … the sound of soul …), Maxime Kontsevich (russian - he talks about « Balance »). WILD ONE Sport & Adventure, Human Stories (52') Language: English Director: Jure Breceljnik Producer: Film IT Country of Origin: 2012 "The quest of a young man, athlete and disabled, to find the love of his mother and resolve the past" In 1977, Philippe Ribière is born in Martinique with the Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome. Abandoned by his parents, he is left to the hospital, where he is bound to spend the first four years of his life and undergo a series of arm and leg operations. -

Content Report

CISCONTENT:CONTENTRREPORTEPORT C ReviewОбзор of новостей audiovisual рынка content производства production и дистрибуции and distribution аудиовизуального in the CIS countries контента Media«»«МЕДИ ResourcesА РЕСУРСЫ МManagementЕНЕДЖМЕНТ» № 1(9)№6№2 13 27 января,1 April, 20122011 тема номераfocus Dearслово cредакциolleaGиues WeУже are в happyпервые to presentдни нового you the года April нам, issue редакof the цCISии youПервый business номер calendar Content Reportfor 2012 выходит do not в forget канун КИНОТЕАТРАЛЬНЫ Й Content Report,Report сразуwhere сталоwe tried понятно, to gather что вthe 2011 mostм toСтарого book timeНового to visitгода, the который major event(наконецто) for televi за- все мы будем усердно и неустанно трудиться. За вершает череду праздников, поэтому еще раз РЫН О К В УКРАИН Е : interesting up-to-date information about rapidly de- sion and media professionals in the CIS region Moscow filM velopingнимаясь contentподготовкой production первого and выпуска distribution обзора markets но хотим- KIEV пожелатьMEDIA WEEK наши 2012м подписчик, Septemberам в11-14, 2011 ЦИФРОВИЗАЦИ Я КА К ofвостей the CIS рынка region. производства As far as most и аудиовизуальног of the locally proо- году2012. найти Organized свой верный by Media путь иResources следовать Manему с- studios (22) ducedконтента series в этом and год TVу ,movies мы с радостью are further обнаружили distributed, упорством,agement company, трудясь неthis покладая unique media рук. У industryкаждого ОСНОВНОЙ ТРЕН Д andчто дажеbroadcast в новогодние mainly inside праздники the CIS р аterritories,бота во мн weо свояproject, дорога, one andно цель only уof нас a kindодн аin – theразвивать CIS and и РАЗВИТИ Я (25) pickedгих продакшнах up the most идет interesting полным хо andдом, original а дальше, projects как улучшатьCentral and отечественный Eastern Europe рынок. -

THE EVOLUTION of MALAYSIAN CARTOON ANIMATION 68 - 82 Faryna Mohd Khalis1, Normah Mustaffa2, Mohd Nor Shahizan Ali3, and Neesa Ameera Mohamed Salim4

COMMITTEE PAGE VOICE OF ACADEMIA Academic Series of Universiti Teknologi MARA Kedah Chief Editor Dr. Junaida Ismail Faculty of Administrative Science and Policy Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Editorial Team Aishah Musa Academy of Language Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Syahrini Shawalludin Faculty of Art and Design, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Etty Harniza Harun Faculty of Business Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Khairul Wanis Ahmad Facility Management & ICT Division, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Siti Natasha Mohd Yatim Research And Industrial Linkages Division, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Azida Hashim Research And Industrial Linkages Division, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Editorial Board Professor Dr M. Nauman Farooqi Faculty of Business & Social Sciences, Mount Allison University, New Brunswick, Canada Professor Dr Kiymet Tunca Caliyurt Faculty of Accountancy, Trakya University, Edirne, Turkey Professor Dr Diana Kopeva University of National and World Economy, Sofia, Bulgaria Associate Professor Dr Roshima Said Faculty of Accountancy, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Associate Professor Dr Zaherawati Zakaria Faculty of Administrative Science and Policy Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Dr Kamarudin Othman Department of Economics, Faculty of Business Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Kedah, Malaysia Dr -

12 Tahapan Dalam Narasi Film Animasi Boboiboy 2 Oscar Gordon Wong1, Imelda Ann Achin2

MUDRA Jurnal Seni Budaya Volume 36, Nomor 3, September 2021 p 316 - 325 P- ISSN 0854-3461, E-ISSN 2541-0407 Perjalanan Pahlawan: 12 Tahapan dalam Narasi Film Animasi Boboiboy 2 Oscar Gordon Wong1, Imelda Ann Achin2 1,2Visual Art Technology, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, 88400 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah [email protected] Tahun 2019 menjadi tahun yang fenomenal bagi perkembangan industri film animasi Malaysia karena telah berhasil dalam dua film animasi superhero secara keseluruhan. Namun, industri film animasi di Malaysia masih kurang kompetitif di peringkat internasional. Hal ini terlihat dari 17 film animasi yang telah diproduksi dari tahun 1998 hingga 2019, hanya dua film animasi superhero yang berhasil mendapat perhatian penonton. Hal ini disebabkan kurangnya pengetahuan tentang konsep dan fungsi karakter superhero dalam film animasi. Oleh karena itu, tujuan utama makalah ini bertujuan untuk mendemonstrasikan bagaimana struktur naratif “Perjalanan Pahlawan” dapat diterapkan dalam BoBoiBoy Movie 2 (2019). Metode penelitian ini melibatkan penggunaan alat analisis video yaitu Kinovea dan menggunakan “Lembaran Kerja Analisis Gambar Bergerak” untuk menjelaskan bagaimana “Perjalanan Pahlawan” film ini dalam menyampaikan cerita. Hasil penelitian ini menemukan bahwa setiap struktur naratif film superhero daripada setengah lingkaran memiliki makna penting dari satu setengah lingkaran ke setengah lingkaran lainnya. Hasilnya, menjelaskan konsep perdamaian dan kekacauan serta stasis dan perubahan struktur naratif film animasi superhero. Makalah ini akan memberikan informasi kepada peneliti tentang pentingnya dan penggunaan pendekatan “Perjalanan Pahlawan” untuk menganalisis film animasi superhero. Kata kunci: superhero, film animasi, struktur naratif, perjalanan pahlawan The Hero’s Journey: 12 Stages in The Narrative of Animation Boboiboy Movie 2 2019 is a phenomenal year for the development of the Malaysian animated film industry as it has successfully produced two superheroes animated films in total. -

Mipcom Edition

*LIST_1013_COVER_LIS_410_COVER 9/19/13 6:13 PM Page 2 The Leading Source for MIPCOM Program EDITION Information www.worldscreenings.com THE MAGAZINE OF PROGRAM LISTINGS OCTOBER 2013 MIP_APP_2013_Layout 1 9/19/13 7:35 PM Page 1 World Screen App For iPhone and iPad DOWNLOAD IT NOW Program Listings | Stand Numbers | Event Schedule | Daily News Photo Blog | Hotel and Restaurant Directories | and more... Sponsored by Brought to you by *LIST_1013_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 9/19/13 6:03 PM Page 598 TV LISTINGS 3 In This Issue 4K MEDIA 53 West 23rd St., 11/Fl. 3 22 New York, NY 10010, U.S.A. 4K Media HBO 9 Story Entertainment Hoho Rights Tel: (1-212) 590-2100 Imagina International Sales 4 IMPS e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 41 Entertainment Incendo A+E Networks website: www.yugioh.com ABC Commercial 23 ABS-CBN Corporation ITV-Inter Medya ITV Studios Global Entertainment 6 Kanal D activeTV Keshet International AFL Productions Ledafilms Alfred Haber Distribution all3media international 24 Stand: 13.11 American Cinema International Lionsgate Entertainment Contact: Shinichi Hanamoto, chmn. & pres. Mance Media 9 Story’s Peg + Cat 7 MarVista Entertainment corp. officer; Kristen Gray, SVP, business affairs; American Greetings Properties MediaBiz Animasia Studio Jennifer Coleman, VP, lic. & mktg.; Kaz Haruna; Peg + Cat (2-5 animated, 80x11 min.) Fol- APT Worldwide 25 Brian Lacey, intl. broadcast dist. cnslt. lows an adorable spirited little girl, Peg, and Armoza Formats MediaCorp Mediatoon Distribution her sidekick, Cat, as they embark on adven- 8 Miramax tures while learning basic math concepts Artear Mission Pictures International Artist View Entertainment Mondo TV S.p.A. -

Betul!: Satu Manifestasi Jati Diri Melayu (Betul! Betul! Betul!: a Manifestation of Malay Identity)

| 133 Betul! Betul! Betul!: Satu Manifestasi Jati Diri Melayu (Betul! Betul! Betul!: A Manifestation of Malay Identity) Norhafidah Ibrahim, Norzaliza Ghazali & Melor Fauzita Md Yusoff Pusat Pengajian Pendidikan dan Bahasa Moden, Kolej Sastera dan Sains, Universiti Utara Malaysia Abstrak: Kajian ini bertujuan untuk melihat unsur-unsur jati diri Melayu dalam filem animasi kartun Upin Ipin Geng: Pengembaraan Bermula. Kajian terhadap filem animasi kartun yang diterbitkan pada tahun 2009 ini menjurus kepada unsur-unsur jati diri Melayu iaitu berteraskan agama Islam, bahasa Melayu dan kebudayaan Melayu. Kartun sepertimana agen komunikasi massa yang lain tergolong dalam kumpulan penyampai budaya yang berkesan. Penciptaan kartun animasi ini dianggap sebagai sesuatu yang unik dan mempunyai nilainya tersendiri kerana mesej yang disampaikan mampu menjadi teladan, perbandingan dan pengajaran kepada masyarakat. Di Malaysia, animasi kartun Melayu yang popular dalam kalangan masyarakat yang menjadi pilihan adalah seperti Upin dan Ipin, Bola Kampung, BoboBoi dan pada satu ketika dulu Usop Sontorian dan Kluang Man. Hasil penelitian yang dilakukan terhadap filem animasi ini, jati diri Melayu merupakan sesuatu yang bernilai dan perlu dipelihara dan diperkukuhkan. Hal ini dapat dicapai apabila agama Islam, bahasa Melayu dan kebudayaan Melayu yang menjadi teras utama kepada jati diri Melayu itu dipelihara. Kesedaran betapa berharganya jati diri perlu ditanam dalam jiwa generasi muda masa kini dalam arus globalisasi yang semakin mengganas. Justeru, filem animasi ini menjadi wadah yang mampu menjana pembinaan jati diri Melayu dalam kalangan masyarakat terutamanya kanak-kanak. Kata Kunci: jati diri Melayu, Islam, bahasa Melayu, budaya Melayu. Abstract: This study aims to identify the elements of Malay identity in Upin Ipin cartoon animated film Geng: Penggembaraan Bermula.