The Portrayals of Symbols Characterizing Malaysian Cultural Values in the Local Children Animated Television Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Malaysian Cartoon Animation

THE EVOLUTION OF MALAYSIAN CARTOON ANIMATION Faryna Mohd Khalis Normah Mustaffa Mohd Nor Shahizan Ali Neesa Ameera Mohamed Salim [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT A cartoon can be defined as an unrealistic style of sketching and or funny figures that can make people laugh. Aside from entertainment purposes, cartoons are also used to send messages without a serious tone and indirectly telling something sarcastically. In April 2019, Malaysia was shocked by the headline that ‘Doraemon’ had been selected to represent the Japanese themed cartoon exhibition in conjunction with Visit Malaysia 2020. Malaysian art activists, specifically those who has a cartoon animation background, were very upset and expressed their dissatisfaction with the news. Local legendary cartoonist Datuk Lat also showed his disappointment and made a stand that a local cartoon character should have been chosen to represent Malaysia. Therefore, this research aims to illustrate the development of Malaysian cartoons from when they first started in newspapers, until their existence today in the form of animation on digital platforms. In sequence, Malaysia produced cartoons in newspapers, magazines, blogs, television and cinema, whereby this is in parallel with the development of technology. From hand- drawn art for ‘Usop Sontorian’ to digital animation for the film ‘Upin dan Ipin’, Malaysians should be more appreciative and proud of our local cartoons rather than those from other countries. Keywords: Local identity, Characteristic, Animation, Comic, Character design. Introduction Cartoons are fundamentally known as entertainment for kids. But due to cultural values, technological development and education, our cliché perception has changed to that cartoons are actually a source of effective communication for all ages (Muliyadi, 2001, 2010, 2015). -

Baju Kurung Sebagai Pakaian Adat Suku Melayu Di Malaysia

Foreign Case Study 2018 Sekolah Tinggi Pariwasata Ambarrukmo Yogyakarta BAJU KURUNG SEBAGAI PAKAIAN ADAT SUKU MELAYU DI MALAYSIA Selfa Nur Insani 1702732 Sekolah Tinggi Pariwasata Ambarrukmo Yogyakarta Abstract : Makalah ini merupakan hasil laporan Foreign Case Study untuk syarat publikasi ilmiah di Sekolah Tinggi Pariwasata Ambarrukmo Yogyakarta dengan Judul Baju Kurung Sebagai Pakaian Adat Suku Melayu di Malaysia. 1. PENDAHULUAN Penulis adalah seorang mahasiswi Sekolah Tinggi Pariwisata Ambarrukmo Yogyakarta (STIPRAM) semester VII jenjang Strata I jurusan Hospitality (ilmu kepariwisataan). Tujuan penulis berkunjung ke Malaysia adalah mengikuti Internship Program yang dilakukan oleh STIPRAM dengan Hotel The Royal Bintang Seremban Malaysia yang dimulai pada 15 September 2015 sampai dengan 11 Maret 2016 [1]. Selain bertujuan untuk Internship Program, penulis juga telah melakukan Program Foreign Case Study (FCS) selama berada di negari itu.Program FCS merupakan salah program wajib untuk mahasiswa Strata 1 sebagai standar kualifikasi menjadi sarjana pariwisata. Program ini meliputi kunjungan kebeberapa atau salah satu negara untuk mengkomparasi potensi wisata yang ada di luar negeri baik itu potensi alam ataupun budaya dengan potensi yang ada di Indoensia. Berbagai kunjungan daya tarik dan potensi budaya negeri malaysia telah penulis amati dan pelajari seperti Batu Cave, China Town, KLCC, Putra Jaya, Genting Highland, Pantai di Port Dikson Negeri Sembilan, Seremban, Arena Bermain I-City Shah Alam, pantai cempedak Kuantan pahang serta mempelajari kuliner khas negeri malaysia yaitu kue cara berlauk dan pakaian tradisional malasyia yaitu baju kurung. Malaysia adalah sebuah negara federasi yang terdiri dari tiga belas negara bagian dan tiga wilayah persekutuan di Asia Tenggara dengan luas 329.847 km persegi. Ibu kotanya adalah Kuala Lumpur, sedangkan Putrajaya menjadi pusat pemerintahan persekutuan. -

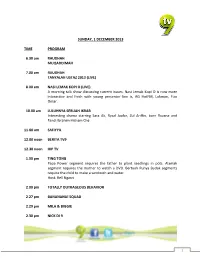

1 SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 Am

SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 am RAUDHAH MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am RAUDHAH TANYALAH USTAZ 2013 (LIVE) 8.00 am NASI LEMAK KOPI O (LIVE) A morning talk show discussing current issues. Nasi Lemak Kopi O is now more interactive and fresh with young presenter line is, AG HotFM, Lokman, Fizo Omar. 10.00 am LULUHNYA SEBUAH IKRAR Interesting drama starring Sara Ali, Ryzal Jaafar, Zul Ariffin, born Ruzana and Fandi Ibrahim Hisham Che 11.00 am SAFIYYA 12.00 noon BERITA TV9 12.30 noon HIP TV 1.00 pm TING TONG Papa Power segment requires the father to plant seedlings in pots. Alamak segment requires the mother to watch a DVD. Bertuah Punya Budak segments require the child to make a sandwich and water. Host: Bell Ngasri 2.00 pm TOTALLY OUTRAGEOUS BEHAVIOR 2.27 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 2.29 pm MILA & BIGGIE 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 1 TEAM UMIZOOMI 3.00 pm NICK DI 9 DORA THE EXPLORER 3.30 pm NICK DI 9 ADVENTURES OF JIMMY NEUTRONS 4.00 pm NICK DI 9 PLANET SHEEN 4.30 pm NICK DI 9 AVATAR THE LEGEND OF AANG 5.00 pm NICK DI 9 SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 5.28 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 5.30 pm BOLA KAMPUNG THE MOVIE Amanda is a princess who comes from the virtual world of a game called "Kingdom Hill '. She was sent to the village to find Pewira Suria, the savior who can end the current crisis. Cast: Harris Alif, Aizat Amdan, Harun Salim Bachik, Steve Bone, Ezlynn 7.30 pm SWITCH OFF 2 The Award Winning game show returns with a new twist! Hosted by Rockstar, Radhi OAG, and the game challenges bands with a mission to save their band members from the Mysterious House in the Woods. -

Malaysian-Omani Historical and Cultural Relationship: in Context of Halwa Maskat and Baju Maskat

Volume 4 Issue 12 (Mac 2021) PP. 17-27 DOI 10.35631/IJHAM.412002 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HERITAGE, ART AND MULTIMEDIA (IJHAM) www.ijham.com MALAYSIAN-OMANI HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL RELATIONSHIP: IN CONTEXT OF HALWA MASKAT AND BAJU MASKAT Rahmah Ahmad H. Osman1*, Md. Salleh Yaapar2, Elmira Akhmatove3, Fauziah Fathil4, Mohamad Firdaus Mansor Majdin5, Nabil Nadri6, Saleh Alzeheimi7 1 Dept. of Arabic Language and Literature, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia Email: [email protected] 2 Ombudsman, University Sains Malaysia Email: [email protected] 3 Dept. of History and Civilization, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia Email: [email protected] 4 Dept. of History and Civilization, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia Email: [email protected] 5 Dept. of History and Civilization, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia Email: [email protected] 6 University Sains Malaysia Email: [email protected] 7 Zakirat Oman & Chairman of Board of Directors, Trans Gulf Information Technology, Muscat, Oman Email: [email protected] * Corresponding Author Article Info: Abstract: Article history: The current re-emergence of global maritime activity has sparked initiative Received date:20.01.2021 from various nations in re-examining their socio-political and cultural position Revised date: 10.02. 2021 of the region. Often this self-reflection would involve the digging of the deeper Accepted date: 15.02.2021 origin and preceding past of a nation from historical references and various Published date: 03.03.2021 cultural heritage materials. -

1 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2012 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 Am

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2012 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 am MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am TANYALAH USTAZ Each episode features an Ustaz to answer all the questions via email or phone call based on the verses of Quran. 8.00 am NASI LEMAK KOPI O A morning talk show programme discussing current and interesting issues. Hosts: Aziz Desa, Abu Talib Husin, Syarifah Nur Syed Ali, Farrah Adeeba, Sharifah Shahirah, Ashraf Muslim, AG Hotfm and Farah Anuar. 10.00 am DENDAM ORANG MINYAK A terrific drama series for the whole family. Casts: Azhan Rani, Latiff Borgiba, Kuza, Aqasha dan Melissa Mauren 11.00 am SUKU (R) 11.30 am REMAJA 2011 (R) 12.00 pm BERITA TV9 12.30 pm SKRIN HUJUNG MINGGU BAKAR BACKHOE 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 WONDERPETS Linny the guinea pig, Tuck the turtle, and Ming-Ming the duckling are class pets in a schoolhouse. When they are left alone in the classroom after each school day ends, they wait for a special phone. 3.00 pm NICK DI 9 GO, DIEGO, GO!. 3.30 pm NICK DI 9 DORA, THE EXPLORER 4.00 pm NICK DI 9 HEY ARNOLD 1 4.30 pm NICK DI 9 THE ADVENTURES OF JIMMY NEUTRON 5.00 pm NICK DI 9 SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 5.28 pm BERITA ADIK Berita Adik is a new program for children on TV9. It will provide the latest information and useful info to the child and family about what is happening and being talked. Hosted by Dayana (Small Idol second season winner), Fimie (Best Child Actor) and Afiq (Actor role in Mahathir's Che Det The Musical). -

Tengkolok As a Traditional Malay Work of Art in Malaysia: an Analysis Of

ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 19, 2020 TENGKOLOK AS A TRADITIONAL MALAY WORK OF ART IN MALAYSIA: AN ANALYSIS OF DESIGN Salina Abdul Manan1, Hamdzun Haron2,Zuliskandar Ramli3, Mohd Jamil Mat Isa4, Daeng Haliza Daeng Jamal5 ,Narimah Abd. Mutalib6 1Institut Alam dan Tamadun Melayu, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. 2Pusat Citra Universiti, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. 3Fakulti Seni Lukis & Seni Reka, Universiti Teknologi MARA 4Fakulti Teknologi Kreatif dan Warisan, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan 5Bukit Changgang Primary School, Banting, Selangor Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received: May 2020 Revised and Accepted: August 2020 ABSTRACT: The tengkolok serves as a headdress for Malay men which have been made infamous by the royal families in their court. It is part of the formal attire or regalia prominent to a Sultan, King or the Yang DiPertuan Besar in Tanah Melayu states with a monarchy reign. As such, the tengkolok has been classified as a three-dimensional work of art. The objective of this research is to analyses the tengkolok as a magnificent piece of Malay art. This analysis is performed based on the available designs of the tengkolok derived from the Malay Sultanate in Malaysia. To illustrate this, the author uses a qualitative method of data collection in the form of writing. Results obtained showed that the tengkolok is a sublime creation of art by the Malays. This beauty is reflected in its variety of names and designs. The name and design of this headdress has proved that the Malays in Malaysia have a high degree of creativity in the creation of the tengkolok. -

Komposisi Muzik We Were Here Dalam Animasi Iban's Migration

KOMPOSISI MUZIK WE WERE HERE DALAM ANIMASI IBAN'S MIGRATION. Wendy James Jengan Sarjana Muda Seni Gunaan dengan Kepujian (Muzik) 201~ KOMPOSISI MUZIK WE WERE HERE DALAM ANIMASI IBAN'S MIGRA TION. WENDY JAMES JENGAN Projek ini merupakan salah satu keperluan untuk Ijazah Sarjana Muda Seni Gunaan dengan Kepujian (Muzik) Fakulti Seni Gunaan dan Kreatif UNIVERSITI MALAYSIA SARAW AK 2013 UNIVERSITI MALAYSIA SARAW AK BORANG PENGESAHAN STATUS TESIS ruDUL KOMPOSISI MUZIK WE WERE HERE DALAM ANIMASI IBAN'S MIGRATION. SESI PENGAJIAN :2009-2013 Saya WENDY JAMES JENGAN mengaku membenarkan tesis * ini disimpan di Pusat Khidmat Maklumat Akademik, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak dengan syarat-syarat kegunaan seperti berikut: 1. Tesis adalah hak milik Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. 2. Pusat Khidmat Maklumat Akademik, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak dibenarkan membuat salinan untuk tujuan pengajian sahaja. 3. Pusat Khidmat Maklumat Akademik, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak dibenarkan membuat pendigitan untuk membangunkan Pangkalan Data Kandungan Tempatan. 4. Pusat Khidmat Maklumat Akademik, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak dibenarkan membuat salinan tesis ini sebagai bahan pertukaran antara institusi pengajian tinggi. 5. *S ila tandakan ("" ) SULIT (Mengandungi maklumat yang berda~ah keselamatan D atau kepentingan seperti termaktub di dalam AKTA RAHS IA RASMI 1972) (Mengandungi maklumat Terhad yang telah ditentukan TERHAD D oleh organisasiibadan di mana penyelidikan G TIDAK TERHAD II TANDATANGAN PENULIS TANDATANGAN PENYELIA Tarikh : )..tl01- {I ~ Tarikh: P4-. or· .;to (;:, Alamat Tetap: 305, lorong 4f4,Tabuan Desa , 93350, Kuching, Sarawak. Catatan: * Tesis dimaksudkan sebagai tesis bagi Ijazah Doktor Falsafah, Sarjana dan Sarjana Muda * lika tesis ini SULIT atau TERHAD, sila lampirkan surat daripada pihak berkuasaJorganisasi berkenaan dengan menyatakan sekali sebab dan tempoh tesis ini perlu dikelaskan sebagai TERHAD. -

The Indian Culture By: Rachita Vinoth

The Indian Culture By: Rachita Vinoth Red, pink, yellow, green, purple, orange, blue, white. Colors float and wave around me. They are in front of me, beside me, behind me, everywhere! There are so many colors that it feels like I am in the sun where all the colors are combined. But to tell you the truth, I am in India. India is a place full of colors, and everywhere you look, everything is so lively and beautiful. There are so many varieties of everything here. India is even called “The Land of Diversity” because of the varieties of food, entertainment, traditions, festivals, clothing, religions, languages, and so much more. Every direction you look, from food to religion, you will see so many unique things. It helps you, it gives you energy, it is the thing that keeps you moving and working - it’s food. There are so many famous foods in India that it is called the land of spices. People from Northern India desire foods like Mughlaifood. Famous foods in Southern India are dosa, idli, and more rice-based dishes. Some foods that people across the country like are chole bhature, all kinds of bread like roti and naan, and of course the all time favorite biryani! Some Indian desserts that are famous are kheer, rasgulla, gulab jamun, and more different varieties. Indians like to play a musical game called antakshari. They also like to watch movies, and the movies are mostly musical, including many types of songs and dances. The movie industry, Bollywood, is almost as big as Hollywood now. -

Here and Elsewhere Recipe Book

Here and Elsewhere Recipe Book A collection of recipes and dishes from the families at Lillian de Lissa Nursery School. Perfect for trying at home with your family. page Pakoras, Dumplings Easy Soda Bread Fasolia or Kidney Bean Curry Fried Rice, Koshari Sanga’s Special Spicy Pork and Rice, Chicken Manila with Rice Chicken Stir Fry, Sweet and Sour Chicken or Fish Mash Potato Chicken Casserole, Jamaine’s Own Homemade Nuggets Chicken, Egg and Vegetable Fried Rice, Chicken Curry Somali Traditional Rice Zurbian or Biryani Rice, Lamb Couscous Yaprakh or Dolma, Spaghetti Bolognese Pancakes, Cornmeal Pudding Lemon Syrup Sponge Pudding Banana Cake Gingerbread Men, Strawberry Clown Cheesecake Mud Cake Pakoras A recipe from Mrs Suliman Ingredients: onions potatoes gram flour spinach salt green chillies dried ground coriander oil How to make it: Chop the vegetables into small pieces and put them in a bowl. Mix together and add chillies, salt and coriander. Add gram flour and mix with water to make a sticky paste. Form small pieces and fry the pakoras. Pakoras are a traditional Pakistani dish. I learnt how to make them from my mother and she learnt from her mother. It has been passed on from generation to generation. Dumplings A recipe from Alicia and her mum Stella Ingredients: flour water sugar milk ground nutmeg for flavour How to make it: Mix the ingredients together and roll into balls. Fry and serve with hotdogs or eggs. These are Nigerian dumplings, but back home they are made with flour ground from dried beans, without sugar and nutmeg. So this is an English version of Nigerian dumplings! Easy Soda Bread A recipe from the Little Red Hen and her helpers, Talia, Abdullah, Kumani, Amirah, Adna, Chaniya, Nuha, Reeyan, Jamaine, Ahmad Badr, Camara, Gracie, Sami, Rojaane and Anaya Ingredients: 170g self-raising flour 170g wholemeal flour ½ tsp salt ½ tsp baking powder 290ml milk or buttermilk How to make it: Mix the milk or buttermilk into the dry ingredients. -

Psychic Interview Ghosts Are Real TRCC Event Golfer's Tee Off Pedal

The Current Volume 19 Issue 1 October 2017 4 10 23 Psychic Interview Pedal Power TRCC Event Ghosts Are Real Cycle to Raise Funds Golfer's Tee Off Volume 19 Issue 1 October 2017 574 New London Turnpike, Norwich, CT 06360 www.threerivers.edu Contents 860-215-9000 Advisor Staff Contributors The Current is the official Kevin Amenta Catalina Anzola student publication of Brissett Cuadros Three Rivers Community Editor Gabrielle Mohan College. The Fall issue Chelsea Ahmed Aimee Sehl will be published two Erin Washington times this semester and Designer is free of charge. The Chelsea Ahmed Special Thanks Current is written, edited, Kathryn Gaffney and designed solely by Front Cover: Dean Ice students. Photo by Kevin Amenta Dr. Mary Ellen Jukoski Alexa Shelton Jean Rienzo The TRCC Copy Center Find and Like Us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TRCCTheCurrent/ 16 23 28 One Pan Meal TRCC Event Festival Weekend Easy College Dinner Golfer's Tee Off Italian and Greek Food Trinity COMPLETE 13 A Message From Your Dental Hygienist Fighting Cavities on Halloween IDP YOUR DEGREE 15 International Coastal Cleanup 2017 Cleaning Up Green Harbor Beach Fall in love with learning again! 18 Colors Soar To The Sky Hot Air Balloon Festival in Plainville Trinity’s Individualized Degree Program (IDP) offers: • Excellent need-based, year-round financial aid 20 Zombie Transformation Tutorial The Dead Never Looked So Good • Accessible academic advising • Full-time or part-time study • Faculty-guided undergraduate research 32 Unleash Your Inner Monster Students Predict Top 2017 Costumes • Phi Theta Kappa (PTK) Scholars Program • 41 majors and many minors Contact us to arrange for a personalized visit. -

MMU Creative Arts

Diecut line CREATIVE MULTIMEDIA & CINEMATIC ARTS Global. Entrepreneurial. Trendsetter. #GoForIt with MMU Diecut line PROSPECTUS www.mmu.edu.my Where Your Future Begins 4 Global. Entrepreneurial. Trendsetter. Diecut line PROFESSOR DATUK DR. AHMAD RAFI MOHAMED ESHAQ CEO/President, Multimedia University Diecut line “Education is the most powerful weapon used to change the world. Our greatest responsibility as educators is to teach our students to think both intensely and critically. By equipping our students with the right tools, knowledge and skills, they can go out into the world and shape their future. As a Premier Digital Tech University and being a trendsetter of the private higher learning provider in Malaysia, we are steadfast in preparing our graduates for leadership roles in their respective disciplines and professions.” — PROFESSOR DATUK DR. AHMAD RAFI MOHAMED ESHAQ CEO/President, Multimedia University Creative Multimedia & Cinematic Arts 3 CREATIVE MULTIMEDIA & CINEMATIC ARTS AT MMU If you have your heart set on a career in Creative Multimedia & Cinematic Arts, MMU is the university for you. MMU offers award-winning, practical and industry-ready degrees that will allow you to make a real and lasting impact in the creative field. We seek to empower our students with expertise and knowledge, and we are committed to an active and dynamic learning environment that will enhance your depth and perception as well as employability. Both our Faculties of Creative Multimedia and Cinematic Arts incorporate constantly updated syllabi originating from reputable institutions across the world as well as our own R&D experts to properly reflect new knowledge and discoveries. Half of our full-time academic staff are international lecturers, along with guest lecturers from Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Singapore who will be able to impart real-life experience to your learning. -

Shifting of Batik Clothing Style As Response to Fashion Trends in Indonesia Tyar Ratuannisa¹, Imam Santosa², Kahfiati Kahdar3, Achmad Syarief4

MUDRA Jurnal Seni Budaya Volume 35, Nomor 2, Mei 2020 p 133 - 138 P- ISSN 0854-3461, E-ISSN 2541-0407 Shifting of Batik Clothing Style as Response to Fashion Trends in Indonesia Tyar Ratuannisa¹, Imam Santosa², Kahfiati Kahdar3, Achmad Syarief4 ¹Doctoral Study Program of Visual Arts and Design, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jl. Ganesa 10 Bandung, Indonesia 2,3,4Faculty of Visual Arts and Design, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jl. Ganesa 10 Bandung, Indonesia. [email protected] Fashion style refers to the way of wearing certain categories of clothing related to the concept of taste that refers to a person’s preferences or tendencies towards a particular style. In Indonesia, clothing does not only function as a body covering but also as a person’s style. One way is to use traditional cloth is by wearing batik. Batik clothing, which initially took the form of non -sewn cloth, such as a long cloth, became a sewn cloth like a sarong that functions as a subordinate, evolved with the changing fashion trends prevailing in Indonesia. At the beginning of the development of batik in Indonesia, in the 18th century, batik as a women’s main clothing was limited to the form of kain panjang and sarong. However, in the following century, the use of batik cloth- ing became increasingly diverse as material for dresses, tunics, and blouses.This research uses a historical approach in observing batik fashion by utilizing documentation of fashion magazines and women’s magazines in Indonesia. The change and diversity of batik clothing in Indonesian women’s clothing styles are influenced by changes and developments in the role of Indonesian women themselves, ranging from those that are only doing domestic activities, but also going to school, and working in the public.