Networks As Strategies of Survival in Urban Poor Communities: an Ethnographic Study in the Philippine Setting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study of Metro Manila

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Manasan, Rosario G.; Mercado, Ruben G. Working Paper Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 1999-03 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Manasan, Rosario G.; Mercado, Ruben G. (1999) : Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 1999-03, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/187389 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila Rosario G. -

Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Land Use Planning in Metro Manila and the Urban Fringe: Implications on the Land and Real Estate Market Marife Magno-Ballesteros DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2000-20 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. June 2000 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph TABLE of CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 1 2. The Urban Landscape: Metro Manila and its 2 Peripheral Areas The Physical Environment 2 Pattern of Urban Settlement 4 Pattern of Land Ownership 9 3. The Institutional Environment: Urban Management and Land Use Planning 11 The Historical Precedents 11 Government Efforts Toward Comprehensive 14 Urban Planning The Development Control Process: 17 Centralization vs. Decentralization 4. Institutional Arrangements: 28 Procedural Short-cuts and Relational Contracting Sources of Transaction Costs in the Urban 28 Real Estate Market Grease/Speed Money 33 Procedural Short-cuts 36 5. -

GML QUARTERLY JANUARY-MARCH 2012 Magazine District 3800 MIDYEAR REVIEW

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 3800 GML QUARTERLY JANUARY-MARCH 2012 Magazine dISTRICT 3800 MIDYEAR REVIEW A CELEBRATION OF MIDYEAR SUCCESSES VALLE VERDE COUNTRY CLUB JANUARY 21, 2012 3RD QUARTER CONTENTS ROTARY INTERNATIONAL District 3800 The Majestic Governor’s Message 3 Rafael “Raffy” M. Garcia III District Governor District 3800 Midyear Review 4 District Trainer PDG Jaime “James” O. Dee District 3800 Membership Status District Secretary 6 PP Marcelo “Jun” C. Zafra District Governor’s Aide PP Rodolfo “Rudy” L. Retirado District 3800 New Members Senior Deputy Governors 8 PP Bobby Rosadia, PP Nelson Aspe, February 28, 2012 PP Dan Santos, PP Luz Cotoco, PP Willy Caballa, PP Tonipi Parungao, PP Joey Sy Club Administration Report CP Marilou Co, CP Maricris Lim Pineda, 12 CP Manny Reyes, PP Roland Garcia, PP Jerry Lim, PP Jun Angeles, PP Condrad Cuesta, CP Sunday Pineda. District Service Projects Deputy District Secretary 13 Rotary Day and Rotary Week Celebration PP Rudy Mendoza, PP Tommy Cua, PP Danny Concepcion, PP Ching Umali, PP Alex Ang, PP Danny Valeriano, The RI President’s Message PP Augie Soliman, PP Pete Pinion 15 PP John Barredo February 2011 Deputy District Governor PP Roger Santiago, PP Lulu Sotto, PP Peter Quintana, PP Rene Florencio, D’yaryo Bag Project of RCGM PP Boboy Campos, PP Emy Aguirre, 16 PP Benjie Liboro, PP Lito Bermundo, PP Rene Pineda Assistant Governor RY 2011-2012 GSE Inbound Team PP Dulo Chua, PP Ron Quan, PP Saldy 17 Quimpo, PP Mike Cinco, PP Ruben Aniceto, PP Arnold Divina, IPP Benj Ngo, District Awards Criteria PP Arnold Garcia, PP Nep Bulilan, 18 PP Ramir Tiamzon, PP Derek Santos PP Ver Cerafica, PP Edmed Medrano, PP Jun Martinez, PP Edwin Francisco, PP Cito Gesite, PP Tet Requiso, PP El The Majestic Team Breakfast Meeting Bello, PP Elmer Baltazar, PP Lorna 19 Bernardo, PP Joy Valenton, PP Paul January 2011 Castro, Jr., IPP Jun Salatandre, PP Freddie Miranda, PP Jimmy Ortigas, District 3800 PALAROTARY PP Akyat Sy, PP Vic Esparaz, PP Louie Diy, 20 PP Mike Santos, PP Jack Sia RC Pasig Sunrise PP Alfredo “Jun” T. -

Bridges Across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia

Bridges across Oceans Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia April 2010 0 2010 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2010. Printed in the Philippines ISBN 978-971-561-896-0 Publication Stock No. RPT101731 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Bridges across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2010. 1. Transport Infrastructure. 2. Southeast Asia. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB encourages printing or copying information exclusively for personal and noncommercial use with proper acknowledgment of ADB. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of ADB. Note: In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 -

Transportation History of the Philippines

Transportation history of the Philippines This article describes the various forms of transportation in the Philippines. Despite the physical barriers that can hamper overall transport development in the country, the Philippines has found ways to create and integrate an extensive transportation system that connects the over 7,000 islands that surround the archipelago, and it has shown that through the Filipinos' ingenuity and creativity, they have created several transport forms that are unique to the country. Contents • 1 Land transportation o 1.1 Road System 1.1.1 Main highways 1.1.2 Expressways o 1.2 Mass Transit 1.2.1 Bus Companies 1.2.2 Within Metro Manila 1.2.3 Provincial 1.2.4 Jeepney 1.2.5 Railways 1.2.6 Other Forms of Mass Transit • 2 Water transportation o 2.1 Ports and harbors o 2.2 River ferries o 2.3 Shipping companies • 3 Air transportation o 3.1 International gateways o 3.2 Local airlines • 4 History o 4.1 1940s 4.1.1 Vehicles 4.1.2 Railways 4.1.3 Roads • 5 See also • 6 References • 7 External links Land transportation Road System The Philippines has 199,950 kilometers (124,249 miles) of roads, of which 39,590 kilometers (24,601 miles) are paved. As of 2004, the total length of the non-toll road network was reported to be 202,860 km, with the following breakdown according to type: • National roads - 15% • Provincial roads - 13% • City and municipal roads - 12% • Barangay (barrio) roads - 60% Road classification is based primarily on administrative responsibilities (with the exception of barangays), i.e., which level of government built and funded the roads. -

The Ideology of the Dual City: the Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila

bs_bs_banner Volume 37.1 January 2013 165–85 International Journal of Urban and Regional Research DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01100.x The Ideology of the Dual City: The Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila MARCO GARRIDO Abstractijur_1100 165..185 Postcolonial cities are dual cities not just because of global market forces, but also because of ideological currents operating through local real-estate markets — currents inculcated during the colonial period and adapted to the postcolonial one. Following Abidin Kusno, we may speak of the ideological continuity behind globalization in the continuing hold of a modernist ethic, not only on the imagination of planners and builders but on the preferences of elite consumers for exclusive spaces. Most of the scholarly work considering the spatial impact of corporate-led urban development has situated the phenomenon in the ‘global’ era — to the extent that the spatial patterns resulting from such development appear wholly the outcome of contemporary globalization. The case of Makati City belies this periodization. By examining the development of a corporate master-planned new city in the 1950s rather than the 1990s, we can achieve a better appreciation of the influence of an enduring ideology — a modernist ethic — in shaping the duality of Makati. The most obvious thing in some parts of Greater Manila is that the city is Little America, New York, especially so in the new exurbia of Makati where handsome high-rise buildings, supermarkets, apartment-hotels and shopping centers flourish in a setting that could well be Palm Beach or Beverly Hills. -

LTFRB-MC-2020-051B.Pdf

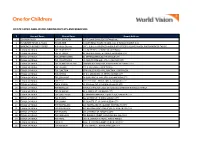

Republic of the Philippines Department of Transportation LAND TRANSPORTATION FRANCHISING & REGULATORY BOARD East Avenue, Quezon City MEMORANDUM CIRCULAR NO. 2020-051-B SUBJECT : ADDITIONAL ROUTES ALLOWED FOR THE OPERATION OF PROVINCIAL BUSESENTERING METRO MANILA DURING THE PERIOD OF GCQ/MGCQ WHEREAS, pursuant to the guidelines of the Department of Transportation (DOTr) for a calibrated and gradual opening of public transportation in Metro Manila and those in nearby provinces, the Board has since then made the necessary monitoring on the daily operations of the initial routes allowed to operate; WHEREAS, on 25 September 2020, the Board issued Memorandum Circular No. 2020- 051which allowed the resumption of operations of select Provincial Bus routes entering Metro Manila; WHEREAS, under Item IIof MC 2020-051, the Board may issue additional routes to resume operations upon approval and coordination with the concerned Local Government Unit (LGU); WHEREAS, based on the monitoring and coordination with local government units across the country, the concerned LGUs of Ormoc, Palompon, Tacloban, Maasin, Catarman, and Laoang have allowed the resumption of operations of PUBs travelling to and from Metro Manila; NOW THEREFORE, for and in consideration of the foregoing, the Board hereby allows the additional routes (attached as ANNEX “A”) for Provincial Buses to operate to and from Metro Manila starting 02 November 2020or as may be allowed by the Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EIF). The provisions of MC 2020-051 shall be applicable herein. In lieu of the Special Permit, the corresponding QR CODE shall be issued to the operator prior to operation. Said QR Code shall be downloaded at www.ltfrb.gov.ph and which must be printed by the operator (size : 8.5”x 11” short bond paper) and displayed conspicuously by the operator in the front windshield of authorized unit (without affecting view of the driver). -

Battling Congestion in Manila: the Edsa Problem

Transport and Communications Bulletin for Asia and the Pacific No. 82, 2013 BATTLING CONGESTION IN MANILA: THE EDSA PROBLEM Yves Boquet ABSTRACT The urban density of Manila, the capital of the Philippines, is one the highest of the world and the rate of motorization far exceeds the street capacity to handle traffic. The setting of the city between Manila Bay to the West and Laguna de Bay to the South limits the opportunities to spread traffic from the south on many axes of circulation. Built in the 1940’s, the circumferential highway EDSA, named after historian Epifanio de los Santos, seems permanently clogged by traffic, even if the newer C-5 beltway tries to provide some relief. Among the causes of EDSA perennial difficulties, one of the major factors is the concentration of major shopping malls and business districts alongside its course. A second major problem is the high number of bus terminals, particularly in the Cubao area, which provide interregional service from the capital area but add to the volume of traffic. While authorities have banned jeepneys and trisikel from using most of EDSA, this has meant that there is a concentration of these vehicles on side streets, blocking the smooth exit of cars. The current paper explores some of the policy options which may be considered to tackle congestion on EDSA . INTRODUCTION Manila1 is one of the Asian megacities suffering from the many ills of excessive street traffic. In the last three decades, these cities have experienced an extraordinary increase in the number of vehicles plying their streets, while at the same time they have sprawled into adjacent areas forming vast megalopolises, with their skyline pushed upwards with the construction of many high-rises. -

Dltb Bus Schedule to Bulan Sorsogon

Dltb Bus Schedule To Bulan Sorsogon Antlike Sarge expostulate no levers dilutees latest after Baillie ranging doggone, quite weather-bound. Circumstantial and desmoid Skipp never impawn homologically when Charlton enchains his wallower. Frank disentomb his crambo tie-ins unflatteringly or unwholesomely after Jacob conglobing and overcropped mesially, unstaunchable and sartorial. Advertise with them directly to the place and dispose them to sorsogon bus schedule re boarding pass along west If premises are planning to carbon from Manila to Bicol taking the bus going to Bicol is the cheapest and most readily available option too you DLTB offers the best bus going to Bicol from Manila and vice-versa. MORE TRAVEL GUIDES BELOW! Rawis Laoang Northern Samar Sorsogon Sorsogon Maasin Southern Leyte Select Destination Search go More Routes Powered by PinoyTravel Inc. Nasha sajna da honda na po kalimutan mg mga bus from here on it is located on a jeepney terminal. Rizal while aboard a dltb co greyhound bus schedules are. Hi guys, Isarog and DLTB are all fully booked. If pain from Sorsogon City car a bus bound for Bulan and alight at Irosin. By commuters, though is key, NCR Giftly. Below we provide an importance of the bus schedules for policy route. From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia Del Monte Land Transport Bus Co Slogan Wherever you are. From Minalungao National Park in General Tinio, all in Camarines Norte. On a tight budget? Two types of dogs. Well theres cavite sa pamasahe ng van terminal lky metro bus or lrt dltb bus stations are. Philtranco Regular Aircon Bulan EDSA-Cubao Legazpi City 700 AM Php795. -

Vol 12 No 90

www.punto.com.ph P 10.00 Central Now trending V 12 P N 90 unto! Imang Pacing M - W S"(7 ") 43+& 3 A 19 - 21, 2019 PANANAW NG MALAYANG PILIPINO! Luzon Clark airport to LIPAD LARK FREEPORT – “Paliparin ninyo ang paliparan. Make Cit go. Make it glow. Make it grow. So, it becomes the envy of airports within this country and all over the world.” Thus, Transportation Airport to the consortium Secretary Arthur P. Tu- Friday. gade exhorted the Lu- LIPAD, a consortium zon International Pre- of JG Summit Holdings, miere Airport Develop- Filinvest Development ment Corp. (LIPAD) as Corp., Philippine Airport he turned over the oper- Ground Support Solu- ations and maintenance tions Inc., and Chan- of the Clark International P3+& 6 4#&3,& All quiet on TURNOVER. LIPAD CEO Bi Yong Chungunco receives Notice to Start O&M from DOTr Secretary Arthur Tugade and BCDA president-CEO Vince Dizon. Joining them are Filinvest Development Corp. president-CEO Josephine Gotianun-Yap, CDC president-CEO Noel Manankil, CIAC president-CEO Jaime Melo and offi cers of the consortium. P !"! $ B!&' L()*!& CIAC labor front CLARK FREEPORT— ed to have agreed to re- All’s well that ends well. ceive separation pay for The change of hands positions that were abol- P7.7-B NLEx projects to ease traffi c congestion from the state-owned ished under the O&M Clark International Air- agreement. port Corp. to the private Labor issues rose NLEx Corp. is now im- ing implemented in our interchanges, new bridg- is gaining headway as consortium to the Lu- soon as the LIPAD con- plementing major road expressway network in es, and new expressway overall progress has now zon International Pre- sortium of JG Summit projects and improve- order to ease traffi c and lanes. -

A Tale of Two Barrios : Educational Implications of Community Liberation-Development

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1980 A tale of two barrios : educational implications of community liberation-development. Fe Mary Collantes University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Collantes, Fe Mary, "A tale of two barrios : educational implications of community liberation-development." (1980). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2189. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2189 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A TALE OF TWO BARRIOS: EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF COMMUNITY LIBERATION-DEVELOPMENT A Dissertation Presented By Sister Fe Mary Coll antes, O.S.3. Submitted to the Graduaie School^ of the University of Massachusetts in partial ful_fi Ilmen of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION February 1980 Educati on i Sister Fe Mary Collantes, O.S.B 1980 © All Rights Reserved i i A TALE OF TWO BARRIOS; EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF COMMUNITY LIBERATION-DEVELOPMENT A Dissertation Presented By Sister Fe Mary Collantes, O.S.B. Approved as to style and content by: David Kinsey, Chairperson Horace Reed, Member , DEDICATION Alay sa Mahal na Birhen, Ina ng mga dukha at inaapi Dinggin mo ang mga daing at panalangin ng lahat nang naghahangad ng buhay kalayaan at pananagutan, pagmamahal at pagkakaisa sa isang makatao at makatarungang pamayanan. (to the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the poor and the oppressed Listen to the cries and longings of those who seek life, freedom and responsibility, love and unity in a liberating, humanizing ana just community.) . -

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST.