Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10.9 De Jesus Precarious Girlhood Dissertation Draft

! ! "#$%&#'()*!+'#,-((./!"#(0,$1&2'3'45!6$%(47'5)#$.!8#(9$*!(7!:$1'4'4$!;$<$,(91$42! '4!"(*2=>??@!6$%$**'(4&#A!B'4$1&! ! ! ;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*! ! ! ! ! E!8-$*'*! F4!2-$!! G$,!H(99$4-$'1!I%-((,!(7!B'4$1&! ! ! ! ! "#$*$42$.!'4!"'&,!:),7',,1$42!(7!2-$!6$J)'#$1$42*! :(#!2-$!;$5#$$!(7! ;(%2(#!(7!"-',(*(9-A!K:',1!&4.!G(<'45!F1&5$!I2).'$*L! &2!B(4%(#.'&!M4'<$#*'2A! G(42#$&,N!O)$0$%N!B&4&.&! ! ! ! ! ! P%2(0$#!>?Q@! ! R!;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*N!>?Q@ ! ! CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Desirée de Jesus Entitled: Precarious Girlhood: Problematizing Reconfigured Tropes of Feminine Development in Post-2009 Recessionary Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Film and Moving Image Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Lorrie Blair External Examiner Dr. Carrie Rentschler External to Program Dr. Gada Mahrouse Examiner Dr. Rosanna Maule Examiner Dr. Catherine Russell Thesis Supervisor Dr. Masha Salazkina Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director December 4, 2019 Dr. Rebecca Duclos Dean Faculty of Fine Arts ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,)-./0!1-)23..45!().62*7,8-9-:;!&*+.:<-;/)*4!%).=*0!.<!>*7-:-:*!?*@*2.=7*:8!-:! (.08ABCCD!&*+*00-.:,)E!'-:*7,! ! ?*0-)F*!4*!G*0/0! '.:+.)4-,!H:-@*)0-8EI!BCJD! ! !"##"$%&'()*+(,--.(/#"01#(2+3+44%"&5()*+6+($14(1(4%'&%7%31&)(3*1&'+(%&()*+(3%&+81)%3(9+:%3)%"&( -

Catherine Breillat

FLACH FILM PRODUCTION, CB FILMS & ARTE FRANCE PRESENT CARLA BESNAÏNOU JULIA ARTAMONOV KÉRIAN MAYAN DAVID CHAUSSE ( LA BELLE ENDORMIE ) A FILM BY CATHERINE BREILLAT In a castle somewhere in a bygone age... The fairy Carabosse cuts the umbilical cord of a newborn babe, a little girl called Anastasia.Three young scatterbrained fairies appear, their cheeks red from running... Too late, says Carabosse, at sixteen the child’s hand will be pierced and she’ll die. The young fairies burst into tears! Their lateness didn’t deserve that. Now they must ward off the fatal curse... They just manage to predict that instead of dying, Anastasia will fall asleep for 100 years. Sleeping for a century is very boring, so they bestow on her the possibility of wandering far and wide in her dreams during those 100 years of sleep... Dans un Château quelque part dans un temps lointain. La fée Carabosse coupe le cordon ombilical d’un nouveau-né, une petite fille prénommée Anastasia. Trois jeunes fées écervelées surgissent, les joues rouges d’avoir couru... Trop tard, dit Carabosse, à l’âge de 16 ans, l’enfant se transpercera la main et mourra. Les jeunes fées éclatent en sanglots ! Leur retard ne méritait pas ça ! Maintenant il faut conjurer le funeste sort… Tout juste peuvent elles prédire qu’au lieu de mourir Anastasia tombera endormie pour 100 ans. Un siècle de sommeil c’est très ennuyeux, elles lui donnent donc le loisir de faire l’école buissonnière en rêve pendant ces 100 années de sommeil…. As opposed to «Bluebeard», I would like to deal with this tale, not as a Contrairement à Barbe Bleue, je voudrais traiter ce conte, non comme story that two little girls tell each other, but as the story of a little girl une histoire que se racontent deux petites filles mais comme l’histoire who is born into a world she has no clear idea of, and so fabricates a même d’une petite fille qui naît, elle ne sait pas encore dans quel monde, child’s world of her own. -

The Beauty of the Real: What Hollywood Can

The Beauty of the Real The Beauty of the Real What Hollywood Can Learn from Contemporary French Actresses Mick LaSalle s ta n f or d ge n e r a l b o o k s An Imprint of Stanford University Press Stanford, California Stanford University Press Stanford, California © 2012 by Mick LaSalle. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data LaSalle, Mick, author. The beauty of the real : what Hollywood can learn from contemporary French actresses / Mick LaSalle. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8047-6854-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Motion picture actors and actresses--France. 2. Actresses--France. 3. Women in motion pictures. 4. Motion pictures, French--United States. I. Title. PN1998.2.L376 2012 791.43'65220944--dc23 2011049156 Designed by Bruce Lundquist Typeset at Stanford University Press in 10.5/15 Bell MT For my mother, for Joanne, for Amy and for Leba Hertz. Great women. Contents Introduction: Two Myths 1 1 Teen Rebellion 11 2 The Young Woman Alone: Isabelle Huppert, Isabelle Adjani, and Nathalie Baye 23 3 Juliette Binoche, Emmanuelle Béart, and the Temptations of Vanity 37 4 The Shame of Valeria Bruni Tedeschi 49 5 Sandrine Kiberlain 61 6 Sandrine -

A Film by Catherine BREILLAT Jean-François Lepetit Présents

a film by Catherine BREILLAT Jean-François Lepetit présents WORLD SALES: PYRAMIDE INTERNATIONAL FOR FLASH FILMS Asia Argento IN PARIS: PRESSE: AS COMMUNICATION 5, rue du Chevalier de Saint George Alexandra Schamis, Sandra Cornevaux 75008 Paris France www.pyramidefilms.com/pyramideinternational/ IN PARIS: Phone: +33 1 42 96 02 20 11 bis rue Magellan 75008 Paris Fax: +33 1 40 20 05 51 Phone: +33 (1) 47 23 00 02 [email protected] Fax: +33 (1) 47 23 00 01 a film by Catherine BREILLAT IN CANNES: IN CANNES: with Cannes Market Riviera - Booth : N10 Alexandra Schamis: +33 (0)6 07 37 10 30 Fu’ad Aït Aattou Phone: 04.92.99.33.25 Sandra Cornevaux: +33 (0)6 20 41 49 55 Roxane Mesquida Contacts : Valentina Merli - Yoann Ubermulhin [email protected] Claude Sarraute Yolande Moreau Michael Lonsdale 114 minutes French release date: 30th May 2007 Screenplay: Catherine Breillat Adapted from the eponymous novel by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly Download photos & press kit on www.studiocanal-distribution.com Produced by Jean-François Lepetit The storyline This future wedding is on everyone’s lips. The young and dissolute Ryno de Marigny is betrothed to marry Hermangarde, an extremely virtuous gem of the French aristocracy. But some, who wish to prevent the union, despite the young couples’ mutual love, whisper that the young man will never break off his passionate love affair with Vellini, which has been going on for years. In a whirlpool of confidences, betrayals and secrets, facing conventions and destiny, feelings will prove their strength is invincible... Interview with Catherine Breillat Film Director Photo: Guillaume LAVIT d’HAUTEFORT © Flach Film d’HAUTEFORT Guillaume LAVIT Photo: The idea “When I first met producer Jean-François Lepetit, the idea the Marquise de Flers, I am absolutely “18th century”. -

Abuse of Weakness

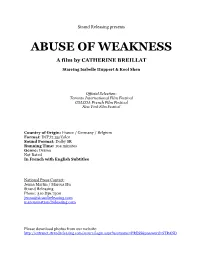

Strand Releasing presents ABUSE OF WEAKNESS A film by CATHERINE BREILLAT Starring Isabelle Huppert & Kool Shen Official Selection: Toronto International Film Festival COLCOA French Film Festival New York Film Festival Country of Origin: France / Germany / Belgium Format: DCP/2.35/Color Sound Format: Dolby SR Running Time: 104 minutes Genre: Drama Not Rated In French with English Subtitles National Press Contact: Jenna Martin / Marcus Hu Strand Releasing Phone: 310.836.7500 [email protected] [email protected] Please download photos from our website: http://extranet.strandreleasing.com/secure/login.aspx?username=PRESS&password=STRAND SYNOPSIS Inspired by director Catherine Breillat’s (FAT GIRL, ROMANCE) true life experiences, her latest film, ABUSE OF WEAKNESS, is an exploration of power and sex. Isabelle Huppert (THE PIANO TEACHER, 8 WOMEN) stars as Maud, a strong willed filmmaker who suffers a stroke. Bedridden, but determined to pursue her latest film project, she sees Vilko (Kool Shen), a con man who swindles celebrities, on a TV talk show. Interested in him for her new film, the two meet and Maud soon finds herself falling for Vilko's manipulative charm as their symbiotic relationship hurdles out of control. DIRECTOR’S NOTE Abuse of weakness is a criminal offense. I used it as the film’s title because I like the sound of it, but also because it has another meaning. Abuse of power. Yes, Maud has strength of character; paradoxically, it’s her weakness. Being an artist means also revealing one’s weaknesses to others. I would have preferred Maud not to be a film director and the story not to seem autobiographical, since even the spectator (at least in intimate movies, and mine are) looks at himself in a mirror. -

Festival Schedule

T H E n OR T HWEST FILM CE n TER / p ORTL a n D a R T M US E U M p RESE n TS 3 3 R D p ortl a n D I n ter n a tio n a L film festi v a L S p O n SORED BY: THE OREGO n I a n / R E G a L C I n EM a S F E BR U a R Y 1 1 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 0 WELCOME Welcome to the Northwest Film Center’s 33rd annual showcase of new world cinema. Like our Northwest Film & Video Festival, which celebrates the unique visions of artists in our community, PIFF seeks to engage, educate, entertain and challenge. We invite you to explore and celebrate not only the art of film, but also the world around you. It is said that film is a universal language—able to transcend geographic, political and cultural boundaries in a singular fashion. In the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous observation, “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler who is foreign,” this year’s films allow us to discover what unites rather than what divides. The Festival also unites our community, bringing together culturally diverse audiences, a remarkable cross-section of cinematic voices, public and private funders of the arts, corporate sponsors and global film industry members. This fabulous ecology makes the event possible, and we wish our credits at the back of the program could better convey our deep appreci- ation of all who help make the Festival happen. -

THE LAST MISTRESS (UNE VIEILLE MAÎTRESSE) a Film by Catherine Breillat

Presents THE LAST MISTRESS (UNE VIEILLE MAÎTRESSE) A Film by Catherine Breillat FILM FESTIVALS CANNES INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2007 TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2007 NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL 2007 CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2007 AFI FILM FESTIVAL 2007 SAN FRANCISCO FILM FESTIVAL 2008 – OPENING NIGHT (114 mins, France/Italy, 2007) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS THE LAST MISTRESS is a smoldering adaptation of Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly’s scandalous 19 th- century novel. Set during the reign of “citizen king” Louis Philippe, it chronicles the surprising betrothal of the aristocratic, handsome Ryno de Marigny (newcomer Fu-ad Aît Aattou) to Hermangarde (Roxane Mesquida of FAT GIRL), a young, beautiful and virginal aristocrat. Lurking in the margins – and in the imaginations of high society’s gossip-hounds – is de Marigny’s older, tempestuous lover of ten years, the feral La Vellini (Argento). Described as, “a capricious flamenca who can outstare the sun,” La Vellini still burns for de Marigny, and she will not go quietly. Though a fascinating departure into more traditional storytelling, THE LAST MISTRESS sees Breillat continuing her career-long interest in the ramifications of female desire, casting Argento as an impassioned independent woman for the ages, but it is also a surprisingly witty and touching – and needless to say sexily explicit - period drama that explores the age-old battle of the sexes. -

Cine-Excess VII: Conference Report by Alex Marlow-Mann

Cine-Excess VII: Conference Report by Alex Marlow-Mann Cine-Excess VII: European Erotic Cinema: Identity, Desire and Disgust was a three-day academic conference and film festival staged at mac birmingham from 15-17 November 2013. A joint collaboration between B-Film: The Birmingham Centre for Film Studies and the University of Brighton, the event was co-organised by Dr. Alex Marlow- Mann and Dr. Xavier Mendik and brought in a range of external partners including local arts organisations like Vivid Projects, academic partners like Birmingham City University, and in-kind sponsorship from Silver Ferox, Arc Media and Classic Miniatures. Conceived as a cross-over industry into academia event aimed at both scholars and the general film-going public, the event brought a number of high-profile industry figures and special guests to Birmingham for the first time. We were delighted to welcome the internationally acclaimed French filmmaker Catherine Breillat, who introduced a rare UK screening of her 1988 film 36 fillette / Virgin and delivered a public Q&A about her controversial explorations of female sexuality (Romance, Anatomy of Hell, Fat Girl, Brief Crossing). Catherine Breillat in conversation with Xavier Mendik and Kate Ince of B-Film. The event also featured cult Italian actor-auteur Francesco Barilli, who discussed working with figures like Bernardo Bertolucci and his own career as both a filmmaker and painter. Barilli also introduced the first ever UK screening of his long-lost masterpiece Pensione paura / Hotel Fear (1977) in a new version subtitled by Alex Marlow-Mann (B- Film) and Oliver Carter (Birmingham City University) especially for this screening. -

Tariff Item / Numéro Tarifaire 9899.00.00 Obscenity and Hate Propaganda Obscénité Et Propagande Haineuse Quarterly List of Ad

Canada Border Agence des services Services Agency frontaliers du Canada Tariff Item / Numéro tarifaire 9899.00.00 Obscenity and Hate Propaganda Obscénité et propagande haineuse Quarterly List of Admissible and Prohibited Titles Liste trimestrielle des titres admissibles et prohibés April to June 2010 / Avril à juin 2010 Prepared by / Préparé par : Prohibited Importations Unit, HQ L’Unité des importations prohibées, AC Quarterly List of Admissible and Prohibited Titles Liste trimestrielle des titres admissibles et prohibés Tariff item 9899.00.00 Numéro tarifaire 9899.00.00 April 1st to June 30th, 2010 1er avril au 30 juin 2010 This report contains a list of titles reviewed by the Prohibited Le rapport ci-joint contient une liste des titres examinés par Importations Unit (PIU), Border Programs Directorate, at l’Unité des importations prohibées (l’UIP), Direction des Headquarters in Ottawa, during the period April 1st to programmes frontaliers, à l’Administration centrale à Ottawa, er June 30th, 2010. Titles for which a determination was entre le 1 avril et le 30 juin 2010. Les titres pour rendered in accordance with section 58 of the Customs Act, or lesquels une décision a été rendue conformément à re-determined as per sections 59 and 60 of the Customs Act, l’article 58 de la Loi sur les douanes ou pour lesquels une during the stated period are listed, along with the related révision a été faite conformément aux articles 59 et 60 de la decision. Titles are categorized by commodity and listed Loi sur les douanes, durant la période en question, sont alphabetically. Where applicable, additional bibliographical indiqués, ainsi que la décision connexe. -

Roxane Mesquida Movie

1 / 4 Roxane Mesquida Movie Roxane Mesquida. Get a pass to watch the new movie I produced #teenageemotions slamdance.com/festival-passes · 684 posts · 64.5k followers · 1,048 .... Buy movie tickets in advance, find movie times, watch trailers, read movie ... Source: TV Line - French actress Roxane Mesquida will play Prince Louis' sister.. Movies · Movie Reviews · Trailers · Film Festivals · Movie Reunions · Movie Previews · Music · Music Reviews · Books · Book Reviews · Author Interviews.. List of Roxane Mesquida Movies and TV Shows on Netflix. If it's on Netflix you'll find it with our search engine. Search below to get started.. Top 10 last week queries: wings hauser net worth, wings hauser movies, wings ... Starring: Stephen Spinella, Roxane Mesquida, Jack Plotnick, Wings Hauser, .... No Horror movie marathon is complete without the Dario Argento directed ... Roxane Mesquida, Claude Sarraute, Yolande Moreau, Michael Lonsdale, Anne.. Roxane Mesquida returns, playing The Actress playing the mid- teen whose virginity is threatened by an Italian tourist. Libero de Rienzo filled .... Browse Roxane Mesquida movies and TV shows available on Prime Video and begin streaming right away to your favorite device. ... Roxane Mesquida, Claude Sarraute, Yolande Moreau, Michael Lonsdale, Anne. ... The original 1977 Dario Argento directed horror film "Suspiria" is officially .... We started on her rooftop to take a few classic Hollywood film star pictures against a sunny backdrop of palm trees. We then took some more shots in her living .... Dig into all the Roxane Mesquida TV Shows and Movies you want on your 30 day free trial. Enjoy unlimited access to TV and Movies from all your favourite ... -

Download File

A Monster for Our Times: Reading Sade across the Centuries Matthew Bridge Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Matthew Bridge All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT A Monster for Our Times: Reading Sade across the Centuries Matthew Bridge This doctoral dissertation looks at several readings and interpretations of the works of the Marquis de Sade, from the eighteenth century to the present. Ever since he was imprisoned under the Old Regime following highly publicized instances of physical and sexual abuse, Sade has remained a controversial figure who has been both condemned as a dangerous criminal and celebrated as an icon for artistic freedom. The most enduring aspect of his legacy has been a vast collection of obscene publications, characterized by detailed descriptions of sexual torture and murder, along with philosophical diatribes that offer theoretical justifications for the atrocities. Not surprisingly, Sade’s works have been subject to censorship almost from the beginning, leading to the author’s imprisonment under Napoleon and to the eventual trials of his mid-twentieth-century publishers in France and Japan. The following pages examine the reception of Sade’s works in relation to the legal concept of obscenity, which provides a consistent framework for textual interpretation from the 1790s to the present. I begin with a prelude discussing the 1956 trial of Jean-Jacques Pauvert, in order to situate the remainder of the dissertation within the context of how readers approached a body of work as quintessentially obscene as that of Sade. -

CATHERINE BREILLAT, 1999) REVIEWS/INTERVIEWS from Radio National with Michael Cathcart

1 CMS 4320 Women and Film Bonner ROMANCE (CATHERINE BREILLAT, 1999) REVIEWS/INTERVIEWS from Radio National with Michael Cathcart [Transcript from broadcast interview on Australian Public Radio] Catherine Breillat is one of France most interesting female film makers and quite a phenomenon. She's a best selling French novelist as well as a film maker. Romance is her sixth and latest film and it reveals sexuality from a completely female point of view. A woman's account of her own feelings, it's an unflinching depiction of various sexual experiences. Marie, the heroine whose husband refuses to have sex with her, sets out on her own journey for sexual satisfaction - and transcendence. The film has been controversial since it was screened last year at European film festivals. Yet it's been released around the world... in Great Britain, Ireland, Turkey and New Zealand. And yes, it will be released soon in Australia although it nearly did not make it. The Office of Film and Literature Classification had refused to classify the film... Its potential Australian distributor, with the suitable ironic name of Potential Films, appealed the ban, which was overturned on the 28th of January 2000. Catherine Breillat spoke to Arts Today's Rhiannon Brown when she brought Romance here last year for the Melbourne Film Festival. Rhiannon Brown: The central character in your film Romance is Marie, a young woman outraged by a society where sex has always been male and romance has always been female. She's in a relationship with Paul, her model boyfriend, who won't make love to her preferring to hide himself amongst his crisp, white sheets watching gymnastics on the television.