CATHERINE BREILLAT, 1999) REVIEWS/INTERVIEWS from Radio National with Michael Cathcart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Film by Catherine BREILLAT Jean-François Lepetit Présents

a film by Catherine BREILLAT Jean-François Lepetit présents WORLD SALES: PYRAMIDE INTERNATIONAL FOR FLASH FILMS Asia Argento IN PARIS: PRESSE: AS COMMUNICATION 5, rue du Chevalier de Saint George Alexandra Schamis, Sandra Cornevaux 75008 Paris France www.pyramidefilms.com/pyramideinternational/ IN PARIS: Phone: +33 1 42 96 02 20 11 bis rue Magellan 75008 Paris Fax: +33 1 40 20 05 51 Phone: +33 (1) 47 23 00 02 [email protected] Fax: +33 (1) 47 23 00 01 a film by Catherine BREILLAT IN CANNES: IN CANNES: with Cannes Market Riviera - Booth : N10 Alexandra Schamis: +33 (0)6 07 37 10 30 Fu’ad Aït Aattou Phone: 04.92.99.33.25 Sandra Cornevaux: +33 (0)6 20 41 49 55 Roxane Mesquida Contacts : Valentina Merli - Yoann Ubermulhin [email protected] Claude Sarraute Yolande Moreau Michael Lonsdale 114 minutes French release date: 30th May 2007 Screenplay: Catherine Breillat Adapted from the eponymous novel by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly Download photos & press kit on www.studiocanal-distribution.com Produced by Jean-François Lepetit The storyline This future wedding is on everyone’s lips. The young and dissolute Ryno de Marigny is betrothed to marry Hermangarde, an extremely virtuous gem of the French aristocracy. But some, who wish to prevent the union, despite the young couples’ mutual love, whisper that the young man will never break off his passionate love affair with Vellini, which has been going on for years. In a whirlpool of confidences, betrayals and secrets, facing conventions and destiny, feelings will prove their strength is invincible... Interview with Catherine Breillat Film Director Photo: Guillaume LAVIT d’HAUTEFORT © Flach Film d’HAUTEFORT Guillaume LAVIT Photo: The idea “When I first met producer Jean-François Lepetit, the idea the Marquise de Flers, I am absolutely “18th century”. -

Abuse of Weakness

Strand Releasing presents ABUSE OF WEAKNESS A film by CATHERINE BREILLAT Starring Isabelle Huppert & Kool Shen Official Selection: Toronto International Film Festival COLCOA French Film Festival New York Film Festival Country of Origin: France / Germany / Belgium Format: DCP/2.35/Color Sound Format: Dolby SR Running Time: 104 minutes Genre: Drama Not Rated In French with English Subtitles National Press Contact: Jenna Martin / Marcus Hu Strand Releasing Phone: 310.836.7500 [email protected] [email protected] Please download photos from our website: http://extranet.strandreleasing.com/secure/login.aspx?username=PRESS&password=STRAND SYNOPSIS Inspired by director Catherine Breillat’s (FAT GIRL, ROMANCE) true life experiences, her latest film, ABUSE OF WEAKNESS, is an exploration of power and sex. Isabelle Huppert (THE PIANO TEACHER, 8 WOMEN) stars as Maud, a strong willed filmmaker who suffers a stroke. Bedridden, but determined to pursue her latest film project, she sees Vilko (Kool Shen), a con man who swindles celebrities, on a TV talk show. Interested in him for her new film, the two meet and Maud soon finds herself falling for Vilko's manipulative charm as their symbiotic relationship hurdles out of control. DIRECTOR’S NOTE Abuse of weakness is a criminal offense. I used it as the film’s title because I like the sound of it, but also because it has another meaning. Abuse of power. Yes, Maud has strength of character; paradoxically, it’s her weakness. Being an artist means also revealing one’s weaknesses to others. I would have preferred Maud not to be a film director and the story not to seem autobiographical, since even the spectator (at least in intimate movies, and mine are) looks at himself in a mirror. -

THE LAST MISTRESS (UNE VIEILLE MAÎTRESSE) a Film by Catherine Breillat

Presents THE LAST MISTRESS (UNE VIEILLE MAÎTRESSE) A Film by Catherine Breillat FILM FESTIVALS CANNES INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2007 TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2007 NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL 2007 CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2007 AFI FILM FESTIVAL 2007 SAN FRANCISCO FILM FESTIVAL 2008 – OPENING NIGHT (114 mins, France/Italy, 2007) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS THE LAST MISTRESS is a smoldering adaptation of Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly’s scandalous 19 th- century novel. Set during the reign of “citizen king” Louis Philippe, it chronicles the surprising betrothal of the aristocratic, handsome Ryno de Marigny (newcomer Fu-ad Aît Aattou) to Hermangarde (Roxane Mesquida of FAT GIRL), a young, beautiful and virginal aristocrat. Lurking in the margins – and in the imaginations of high society’s gossip-hounds – is de Marigny’s older, tempestuous lover of ten years, the feral La Vellini (Argento). Described as, “a capricious flamenca who can outstare the sun,” La Vellini still burns for de Marigny, and she will not go quietly. Though a fascinating departure into more traditional storytelling, THE LAST MISTRESS sees Breillat continuing her career-long interest in the ramifications of female desire, casting Argento as an impassioned independent woman for the ages, but it is also a surprisingly witty and touching – and needless to say sexily explicit - period drama that explores the age-old battle of the sexes. -

Tariff Item / Numéro Tarifaire 9899.00.00 Obscenity and Hate Propaganda Obscénité Et Propagande Haineuse Quarterly List of Ad

Canada Border Agence des services Services Agency frontaliers du Canada Tariff Item / Numéro tarifaire 9899.00.00 Obscenity and Hate Propaganda Obscénité et propagande haineuse Quarterly List of Admissible and Prohibited Titles Liste trimestrielle des titres admissibles et prohibés April to June 2010 / Avril à juin 2010 Prepared by / Préparé par : Prohibited Importations Unit, HQ L’Unité des importations prohibées, AC Quarterly List of Admissible and Prohibited Titles Liste trimestrielle des titres admissibles et prohibés Tariff item 9899.00.00 Numéro tarifaire 9899.00.00 April 1st to June 30th, 2010 1er avril au 30 juin 2010 This report contains a list of titles reviewed by the Prohibited Le rapport ci-joint contient une liste des titres examinés par Importations Unit (PIU), Border Programs Directorate, at l’Unité des importations prohibées (l’UIP), Direction des Headquarters in Ottawa, during the period April 1st to programmes frontaliers, à l’Administration centrale à Ottawa, er June 30th, 2010. Titles for which a determination was entre le 1 avril et le 30 juin 2010. Les titres pour rendered in accordance with section 58 of the Customs Act, or lesquels une décision a été rendue conformément à re-determined as per sections 59 and 60 of the Customs Act, l’article 58 de la Loi sur les douanes ou pour lesquels une during the stated period are listed, along with the related révision a été faite conformément aux articles 59 et 60 de la decision. Titles are categorized by commodity and listed Loi sur les douanes, durant la période en question, sont alphabetically. Where applicable, additional bibliographical indiqués, ainsi que la décision connexe. -

Download File

A Monster for Our Times: Reading Sade across the Centuries Matthew Bridge Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Matthew Bridge All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT A Monster for Our Times: Reading Sade across the Centuries Matthew Bridge This doctoral dissertation looks at several readings and interpretations of the works of the Marquis de Sade, from the eighteenth century to the present. Ever since he was imprisoned under the Old Regime following highly publicized instances of physical and sexual abuse, Sade has remained a controversial figure who has been both condemned as a dangerous criminal and celebrated as an icon for artistic freedom. The most enduring aspect of his legacy has been a vast collection of obscene publications, characterized by detailed descriptions of sexual torture and murder, along with philosophical diatribes that offer theoretical justifications for the atrocities. Not surprisingly, Sade’s works have been subject to censorship almost from the beginning, leading to the author’s imprisonment under Napoleon and to the eventual trials of his mid-twentieth-century publishers in France and Japan. The following pages examine the reception of Sade’s works in relation to the legal concept of obscenity, which provides a consistent framework for textual interpretation from the 1790s to the present. I begin with a prelude discussing the 1956 trial of Jean-Jacques Pauvert, in order to situate the remainder of the dissertation within the context of how readers approached a body of work as quintessentially obscene as that of Sade. -

Catherine Breillat. Adolescencia, Subversión Y Ritos De Paso

Del 5 al 27 de febrero Catherine Breillat. Adolescencia, subversión y ritos de paso Los días 5 y 6 de febrero, Catherine Breillat estará disponible para entrevistas La Casa Encendida presenta a una de las directoras más prolija, controvertida y transgresora del cine francés con el ciclo “Catherine Breillat. Adolescencia, subversión y ritos de paso”, una oportunidad para descubrir una visión reveladora sobre el tránsito de la adolescencia femenina, los cambios corporales que acontecen, el despertar al deseo sexual, la pérdida de la virginidad y donde, en lo cotidiano, se insertan las fantasías eróticas. Catherine Breillat (Bressuire, Francia, 1948) tiene una larga y coherente trayectoria en el cine que dura más de cuarenta años. Fue tras el estreno de su polémica Romance (1999) – película con escenas de sexo real destinada al circuito comercial– cuando su nombre salió de los círculos de los expertos en cine y literatura para ocupar un lugar en el ámbito internacional. La visión de Breillat rompe con los estereotipos de género y los roles sexuales, contraviene a nivel visual los condicionamientos familiares y las normas sociales, y reconceptualiza las nociones de obscenidad, impureza, pornografía o abyección, en un posicionamiento donde, de nuevo, lo íntimo y lo personal es político. Su obra resulta tan controvertida y perturbadora por negarse a someter el cuerpo femenino al poder de la mirada masculina, dejando así que la mirada femenina construya. Cuestiona también que el deseo femenino no sea más que una respuesta al deseo del otro masculino. El ciclo se centra en cuatro de sus películas que tratan más de cerca el tema de la adolescencia femenina, momento de transformación física y psicológica y de iniciación a la sexualidad adulta, que la directora representa como un rito de paso, donde las heroínas se buscan a sí mismas y pasan por diferentes pruebas. -

Porn Star, Vivid Entertainment Group Best Actor – Video

Nominations for 2004 AVN Awards Show Best Film Compulsion, Elegant Angel Productions Heart of Darkness, Vivid Entertainment Group Heaven's Revenge, Vivid Entertainment Group Looking In, Vivid Entertainment Group Snakeskin, Erotic Angel Sordid, Vivid Entertainment Group Best Video Feature Acid Dreams, Private North America Barbara Broadcast Too!, VCA Pictures Beautiful, Wicked Pictures Improper Conduct, Wicked Pictures Little Runaway, Multimedia Pictures Magic Sex, Simon Wolf Productions New Wave Hookers 7, VCA Pictures No Limits, Digital Playground Not a Romance, Wicked Pictures Perverted Stories The Movie, JM Productions Phoenix Rising 2, New Sensations Rawhide, Adam & Eve Riptide, Sin City Entertainment Stud Hunters, Adam & Eve Tricks, Vivid Entertainment Group Young Sluts Inc. 12, Hustler Video Best Gonzo Tape Ass Cleavage, Zero Tolerance Crack Her Jack, John Leslie/Evil Angel Productions Double Parked, DVSX Flesh Hunter 5, Jules Jordan/Evil Angel Productions Hot Bods & Tail Pipe 28, Celestial Productions International Tushy, Seymore Butts/Pure Play Media Jack's Playground 2, Digital Playground Just Over Eighteen 5, Red Light District Multiple P.O.V., Vouyer Productions/Red Light District No Cum Dodging Allowed, Red Light District Runaway Butts 6, Joey Silvera/Evil Angel Productions Shane's World 32: Campus Invasion, Shane’s World Studios/New Sensations Terrible Teens, Metro Studios The Voyeur 24, John Leslie/Evil Angel Productions World Sex Tour 27, Anabolic Video Best Gonzo Series Balls Deep, Anabolic Video Buttman, Evil Angel Productions -

THE SLEEPING BEAUTY from the Internationally Acclaimed Director of Bluebeard, the Last Mistress, Fat Girl, Romance, Sex Is Comedy, and Anatomy of Hell

FOR MORE INFORMATION: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Samantha Klinger - 310.836.7500 Street Date - November 8, 2011 [email protected] Pre-Book Date - October 11, 2011 THE SLEEPING BEAUTY From the internationally acclaimed director of Bluebeard, The Last Mistress, Fat Girl, Romance, Sex Is Comedy, and Anatomy Of Hell On Tuesday, November 8, 2011 Strand Releasing proudly releases on DVD the latest of French provocateur Catherine Breillat's subverted fairytales, THE SLEEPING BEAUTY, a twisted retelling that ends far from "happily ever after". Starring Clara Besnaïnou, Julia Artamonov, Kerian Mayan, and David Chausse. Based on a tale by Charles Perrault, three fairies alter a curse on a young princess who is destined to die at an early age. Instead she embarks upon a hundred-year sleep, in which she is allowed to live a full and vivid life within her dreams. She experiences a sexual awakening that reshapes her view on Prince Charming when she has no clear perception of reality. Charles Perrault's Stories or Fairy Tales From Bygone Eras has drawn countless retellings in the form of animated films, ballets and children's books. BLUEBEARD was the first film Catherine Breillat deconstructed from one of his classic tales as THE SLEEPING BEAUTY is her second quintessential fairytale retold for adults and SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS will be the final installment of her vision to the trilogy. Winner of the Art Cinema Award (C.I.A.E.) at the Venice International Film Festival. An Official Selection at the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema in New York, ColCoa (French Film Festival in Los Angeles), Toronto, and San Francisco International Film Festivals. -

The Viewing Habits of Users of Sexually Explicit Movies: a Hawke's

The Viewing Habits of Users of Sexually Explicit Movies: a Hawke’s Bay sample Venezia Kingi Elisabeth Poppelwell Report for the Office of Film and Literature Classification December 2005 Crime and Justice Research Centre Victoria University of Wellington ISBN 0-477-10010-4 Copyright Contents Foreword 3 Acknowledgements 4 Chapter 1 Introduction 6 Chapter Methodology 8 2.1 Methods 8 2.2 Ethical issues and safety procedures 8 2.3 Research methods and number of participants 9 2.4 Interview schedule and information sheet 9 2.5 Analysis of responses 10 2.7 Interviews 11 .8 Couples who were interviewed 14 .9 Women who were interviewed 14 .10 Maori participants 15 .11 Limitations of the research 15 Chapter 3 Findings 16 3.1 Introduction 16 3.2 Sourcing sexually explicit movies 16 3.3 Viewing sexually explicit movies 17 3.4 Viewing preferences 0 3.5 Reasons for viewing sexually explicit movies 1 3.6 Trying out activities seen in sexually explicit movies 3 3.7 Views on the content of sexually explicit movies 6 3.8 Internet usage 35 3.9 Other media usage 36 3.10 Views about watching sexually explicit movies 37 3.11 The impact of viewing sexually explicit movies 43 3.12 Is the sexual behaviour shown in movies realistic? 44 3.13 Views on who watches sexually explicit movies 46 3.14 Views on censorship of sexually explicit movies in New Zealand 48 3.15 Reasons for taking part in the research 50 3.16 In summary 5 Research for the Office of Film and Literature Classification Chapter 4 Comparing the two studies 55 4.1 Introduction 55 4.2 Samples 55 4.3 -

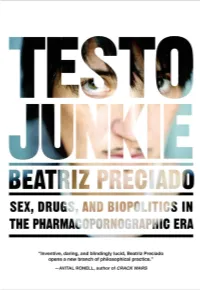

Testo Junkie Is a Key Text to Comprehend the Deep Interconnectedness of Sex and Drugs Today.”

“ Testo Junkie is a wild ride. Preciado leaves the identity politics of taking T to others, and instead, in the tradition of William S. Burroughs, Kathy Acker, and Jean Genet, s/he conducts a wild textual experiment. The results are spectacular . The gendered body will never be the same again.” —JACK HALBERSTAM, author of THE QUEER ART OF FAILURE “ Beatriz Preciado’s brilliant book oscillates between high theory and the surging rush of testosterone. Flush with elegant theoretical formulations, lascivious sex nar- ratives, and astute histories of gender, Testo Junkie is a key text to comprehend the deep interconnectedness of sex and drugs today.” —JOSÉ ESTEBAN MUÑOZ, author of CRUISING UTOPIA “The ideas in Beatriz Preciado’s pornosophical gem are a thousand curious fingers slipped beneath the underpants of conventional thinking. Teach the sex scenes in your seminars, and read the flights of theory aloud to your latest lover amid a tangle of sweaty sheets.” —SUSAN STRYKER, author of THE TRANSGENDER STUDIES READER “ Testo Junkie is unlike anything I’ve ever read. Beatriz Preciado has produced a volume of work that goes far beyond memoir to create an entirely new way of understanding not only the history of sex, gender, and the body, but of life as we have come to know it. Powerful and disturbing in the most pleasurable way.” —DEL LAGRACE VOLCANO, author of FEMMES OF POWER “ Beatriz Preciado offers an exhilarating and sometimes shattering portrait of how gen- dershapesthewaysweliveandfuckandgrieveandfightandlove.Testo Junkie is a fearless chronicle of the gender revolution currently in progress. Anyone who has a gender—or has dispensed with one—should read this book.” —GAYLE SALAMON, author of ASSUMING A BODY “ Inventive, daring, and blindingly lucid, Beatriz Preciado opens a new branch of phil- osophical practice. -

Vogov.Io Contents

WHITE PAPER Blockchain penetrates deeper VERSION 1.1 August 7, 2018 www.vogov.io Contents Introduction 3 Background 5 Fan Engagement 5 Ease of Purchase 5 Cryptocurrency Acceptance and Business Usage 7 Extended Cryptocurrency Billing 8 Low Fees 9 Anonymity 10 Market Cap 10 OGO coin: Token Economy 12 Triple Token Value 13 Token Demand Generation 15 Limited Supply 15 Burn Mechanism 16 Partnerships 17 Liquidity Pool 18 VogoV: A Decentralized Adult Film Studio 20 Gonzo 20 Interactiveness, Decentralization and Voting 21 OgoShift: An Adult-Industry Сryptocurrency Infrastructure 25 Wallet 26 Merchant Account 27 Marketplace 29 Exchange 30 Crowdsale Conditions and Terms 31 Token and Crowdsale Details 31 Crowdsale Rounds Difference 32 Crowdsale Bonuses 34 Token Distribution 35 Crowdsale Success and Project Implementation 36 Roadmap 37 Advisors 39 Team 40 Conclusion 43 Disclaimer 44 Introduction Blockchain technology and cryptocurrency has created a signifcant worldwide technological shift that has also affected the adult entertainment industry. VogoV is taking advantage of this technological shift and the limited competition in the open market to create a practical token ecosystem combining the adult entertainment industry and cryptocurrency. We are changing the way the adult entertainment industry utilizes and interacts with cryptocurrency, starting with its acceptance and business usage and ending up with the non-technological value that a token may bring. At present, most adult businesses only utilize cryptocurrency as an alternative payment method. We believe that cryptocurrency can be used for much more. VogoV plans to embark on a grand experiment to investigate how willing the adult entertainment industry is to accept and work within the blockchain environment. -

Portrayal of the Disabled Body in Catherine Breillat's Abus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by espace@Curtin ‘C’était moi mais ce n’était pas moi’: portrayal of the disabled body in Catherine Breillat’s Abus de faiblesse (2013) Kath Dooley [[email protected]] Department of Screen Arts, Curtin University, Kent St, Bentley WA 6102, Australia Writer/director Catherine Breillat's most recent film Abus de faiblesse (2013) explores an important moment of bodily transition: the change from able to disabled body. This semi-autobiographic film follows the story of film director, Maud (Breillat's alter ego), who forms a destructive relationship with a conman, Vilko, after she suffers a disabling stroke. This film shows consistency with Breillat's previous work in its exploration of the constructed nature of the female body onscreen. In the past the filmmaker has portrayed moments of trauma and transition (such as childbirth, loss of virginity or rape) to subvert processes of objectification. The article argues that Abus de faiblesse challenges and subverts representation of the post-menopausal and disabled body onscreen. The film interrogates binary oppositions such as able/disabled and independence/dependency to challenge representations of the disabled body as 'other'. With reference to scholarly work on disability (Mitchell and Snyder 2006) and the aging female body (Markson 2003; Ussher 2006) the article suggests that Maud's sadomasochistic relationship with Vilko is driven by a quest to retain her subjectivity after her stroke. The article demonstrates that the film dissects the feared and the unknown territory of the aging female body.