The Absence of Presence. Homiletical Reflections on Luther's Notion of the Masks of God (Larvae Dei)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry: Grades 7 & 8

1 Poetry: Grades 7 & 8 Barter Casey at the Bat The Creation The Crucifixion The Destruction of Sennacherib Do not go gentle into that good night From “Endymion,” Book I Forgetfulness The Highwayman The House on the Hill If The Listeners Love (III) The New Colossus No Coward Soul Is Mine One Art On His Blindness On Turning Ten Ozymandias Paul Revere's Ride The Road Goes Ever On (from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings) Sonnet Spring and Fall Stanzas th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 2 The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls The Village Blacksmith The World th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 3 Barter Sara Teasdale Life has loveliness to sell, All beautiful and splendid things, Blue waves whitened on a cliff, Soaring fire that sways and sings, And children's faces looking up Holding wonder in a cup. Life has loveliness to sell, Music like a curve of gold, Scent of pine trees in the rain, Eyes that love you, arms that hold, And for your spirit's still delight, Holy thoughts that star the night. Spend all you have for loveliness, Buy it and never count the cost; For one white singing hour of peace Count many a year of strife well lost, And for a breath of ecstasy Give all you have been, or could be. † th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 4 Casey at the Bat Ernest Lawrence Thayer The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day: The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play, And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same, A pall-like silence fell upon the patrons of the game. -

The Lonely Society? Contents

The Lonely Society? Contents Acknowledgements 02 Methods 03 Introduction 03 Chapter 1 Are we getting lonelier? 09 Chapter 2 Who is affected by loneliness? 14 Chapter 3 The Mental Health Foundation survey 21 Chapter 4 What can be done about loneliness? 24 Chapter 5 Conclusion and recommendations 33 1 The Lonely Society Acknowledgements Author: Jo Griffin With thanks to colleagues at the Mental Health Foundation, including Andrew McCulloch, Fran Gorman, Simon Lawton-Smith, Eva Cyhlarova, Dan Robotham, Toby Williamson, Simon Loveland and Gillian McEwan. The Mental Health Foundation would like to thank: Barbara McIntosh, Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities Craig Weakes, Project Director, Back to Life (run by Timebank) Ed Halliwell, Health Writer, London Emma Southgate, Southwark Circle Glen Gibson, Psychotherapist, Camden, London Jacqueline Olds, Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard University Jeremy Mulcaire, Mental Health Services, Ealing, London Martina Philips, Home Start Malcolm Bird, Men in Sheds, Age Concern Cheshire Opinium Research LLP Professor David Morris, National Social Inclusion Programme at the Institute for Mental Health in England Sally Russell, Director, Netmums.com We would especially like to thank all those who gave their time to be interviewed about their experiences of loneliness. 2 Introduction Methods A range of research methods were used to compile the data for this report, including: • a rapid appraisal of existing literature on loneliness. For the purpose of this report an exhaustive academic literature review was not commissioned; • a survey completed by a nationally representative, quota-controlled sample of 2,256 people carried out by Opinium Research LLP; and • site visits and interviews with stakeholders, including mental health professionals and organisations that provide advice, guidance and services to the general public as well as those at risk of isolation and loneliness. -

The Lonely Page

The Lonely Page Edited by Emily DeDakis © eSharp 2011 eSharp University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8QQ http://www.gla.ac.uk/esharp © eSharp 2011 No reproduction of any part of this publication is permitted without the written permission of eSharp eSharp The Lonely Page Contents Introduction 5 Emily DeDakis, editor (Queen’s University Belfast) Suicide, solitude and the persistent scraping 10 Shauna Busto Gilligan (NUI Maynooth/ University of Glamorgan) Game: A media for modern writers to learn from? 20 Richard Simpson (Liverpool John Moores University) Imaginary ledgers of spectral selves: A blueprint of 29 existence Christiana Lambrinidis (Centre for Creative Writing & Theatre for Conflict Resolution, Greece) ‘The writing is the thing’: Reflections on teaching 36 creative writing Micaela Maftei (University of Glasgow) The solitude room 47 Cherry Smyth (University of Greenwich) How critical reflection affects the work of the writer 55 Ellie Evans (Bath Spa University) Beyond solitude: A poet’s and painter’s collaboration 66 Stephanie Norgate (University of Chichester) & Jayne Sandys-Renton (University of Sussex) Making the Statue Move: Balancing research within 81 creative writing Anne Lauppe-Dunbar (Swansea University, Wales) 3 eSharp The Lonely Page Two inches of ivory: Short-short prose and gender 92 Laura Tansley (University of Glasgow) The beginnings of solitude 102 David Manderson (University of West Scotland) An extract from the novel The Bridge 110 Karen Stevens (University of Chichester) Poems from the sequence Distance 116 Cath Nichols (Lancaster University) An extract from the novel Lost Bodies 120 David Manderson (University of West Scotland) From the poem Now you're a woman 126 Cherry Smyth (University of Greenwich) Parts One, Two and Three 127 Laura Tansley (University of Glasgow) Marthé 134 Barbara A. -

Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes.Xlsx

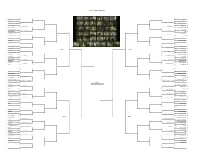

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last 57 56 Eye of the Beholder 1 Time Enough at Last Eye of the Beholder 32 The Fever 4 5 The Mighty Casey 32 16 A World of Difference 25 19 The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 I Shot an Arrow into the Air A Most Unusual Camera 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 35 41 A Most Unusual Camera 17 8 Third from the Sun 44 37 The Howling Man 8 Third from the Sun The Howling Man 25 A Passage for Trumpet 16 Nervous22 Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 34 45 The Invaders 9 Love Live Walter Jameson The Invaders 24 The Purple Testament 25 13 Dust 24 5 The Hitch-Hiker 52 41 The After Hours 5 The Hitch-Hiker The After Hours 28 The Four of Us Are Dying 8 19 Mr. Bevis 28 12 What You Need 40 31 A World of His Own 12 What You Need A World of His Own 21 Escape Clause 19 28 The Lateness of the Hour 21 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 37 48 The Silence 4 And When the Sky Was Opened The Silence 29 The Chaser 21 11 The Mind and the Matter 29 13 A Nice Place to Visit 35 35 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit The Night of the Meek 20 Perchance to Dream 24 24 The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Season 2 6 Walking Distance 37 43 Nick of Time 6 Walking Distance Nick of Time 27 Mr. -

Why Did Tliu Is a Special Return Encasement and We Confidently Present This Mast-- Er Keystone Fttnfaat Tor Laughing Cluunbcniuild Wanted

TEN PAGES DAILY EAST OREGONIAN, PENDLETON, OREGON, SATURDAY, AUGUST 12. 1916. PAGE FIVE wear .nrm ,. n mi h mi M 1 .jkmt. i M h vii;i ('unnns ha m home this mon re she hail been vls- - iting lor aevera at ML--8 Maflflm Burgess, who has mm ' Willi in The THEATRE in ii visiting relatives Dalles fur the past few 'lays, li lt PROGRAM for Sea-sid- Sunday and Monday SATURDAY'S Miss Sarah Bmltb will arrive In the 5 mm n UK from Berkeley, Cal., to be a OLIVER MOROSCO PRESENTS houat guest Of, Mrs. Charles Heard. "THE LION'S NEMESIS" Miss Smith Is en mute to her home Grande. 2 Acts, Margaret Gibson, William Clifford and the Bostock Animals.. in I.a Otto Serrell, prominent' Vansycle Edna Goodrich Car- "JERRY AND THE MOON- - "THAT GAL OF BURKE'S" Bud Fisher's Comic In rmer. came in this morning on the SHINERS" toons, N. P. train. With a Cast of Unusual Excellence, in Laughable comedy with Western drama. Anna Little MUTT & JEFF THIRST and Frank Borzaga. QUENCHERS." i Charles W. Mi-I- han, former local George Ovey. newspaper man. arrived In Pendleton today from Salt Lake, joining Mrs ADULTS 10c CHILDREN 5c Me ghan who Is visiting her parents, The Making Mr. and Mrs. John Haihy, Jr Miss Juste Reed of Walla Walla, SUNDAY'S PROGRAM was in the city yesterday. of Maddalena j W. Kollons, division superintendent! i ii William Fox Presents of the ., Is in the city. EDNA GOODRICH well-know- Minnie Kinnear of Walla Walla, THt CLIVtfl MO" '.f 0 PHOT0rt--t CO A Thrilling Picturization of the n Play. -

Songs of the Cattle Trail and Cow Camp

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism English, Department of January 1919 Songs of the Cattle Trail and Cow Camp John A. Lomax M.A. University of Texas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Lomax, John A. M.A., "Songs of the Cattle Trail and Cow Camp" (1919). University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism. 13. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SONGS OF THE CATTLE TRAIL AND COW CAMP COLLECTED BY JOHN A. LOMAX, B.A., M.A. Executive Secretary Ex-Students' Association• ~. the University of Texas. For three years Sheldon Fellow from Harvard University 0 '\9 for the Collection of American Ballads; Ex-President THE MACMILLAN COMPANY American Folk-Lore Society. Collector of ow YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO· DALLAS ATLANTA· SAN FRANCISCO "Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier MACMILLAN & CO., LIMITED Ballads"; joint author with Dr. LONDON· BOMBAY· CALCUTTA H. Y. Benedict of "The MELBOURNE Book of Texas." THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TORONTO WITH A FOREWORD BY WILLIAM LYON PHELPS Jaew !!Jork THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1919 A./Z right. t'eeet'ved "THAT THESE DEAR FRIENDS I LEAVE BEHIND MAY KEEP KIND HEARTS' REMEMBRANCE OF THE LOVE WE HAD." Solon. -

Season4article.Pdf

N.B.: IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE TWO-PAGE VIEW IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. VIEW/PAGE DISPLAY/TWO-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT) and ENABLE SCROLLING “EVENING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” (minus ‘The’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019 The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Author permissions are required to reprint all or part of this work. www.twilightzonemuseum.com * www.facebook.com/twilightzonemuseum Preface At this late date, little has not been said about The Twilight Zone. It’s often imitated, appropriated, used – but never remotely matched. From its quiet and decisively non-ostentatious beginnings, it steadily grew into its status as an icon and televisional gemstone…and not only changed the way we looked at the world but became an integral part of it. But this isn’t to say that the talk of it has been evenly distributed. Certain elements, and full episodes, of the Rod Serling TV show get much more attention than others. Various characters, plot elements, even plot devices are well-known to many. But I dare say that there’s a good amount of the series that remains unknown to the masses. In particular, there has been very much less talk, and even lesser scholarly treatment, of the second half of the series. This “study” is two decades in the making. It started from a simple episode guide, which still exists. Out of it came this work. The timing is right. In 2019, the series turns sixty years old. -

University of Nevada, Reno Between the Pit of Man's Fears and The

University of Nevada, Reno Between the Pit of Man’s Fears and the Summit of his Knowledge: Rethinking Masculine Paradigms in Postwar America via Television’s The Twilight Zone A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Erin Kathleen Cummings Dr. C. Elizabeth Raymond/Thesis Advisor August 2011 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by ERIN KATHLEEN CUMMINGS entitled Between the Pit of Man’s Fears and the Summit of his Knowledge: Rethinking Masculine Paradigms in Postwar America via Television’s The Twilight Zone be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Alicia Barber, Ph.D., Committee Member Dennis Dworkin, Ph.D., Committee Member Stacey Burton, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School August, 2011 i Abstract During the opening credits of the first season of The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling defined the Twilight Zone as another dimension located “between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge.” Serling’s creative commentary theoretically speaks to the process through which gender paradigms have been constructed and transformed over time. As Gail Bederman explains in Manliness and Civilization (1995), gender construction is a historical, dynamic process in which men and women actively transform gender ideals by blending, adapting, and renegotiating older models in conjunction with concurrent modes. Between the summit of knowledge (that which is known) and the pit of fear (that which is unknown) gender is indeed constructed. -

The Lonely Island

EDINBURGH, THE SETTLEMENT OF TRISTAN DA CUNHA, FROM THE SEA THE LONELY ISLAND BY ROSE ANNIE ROGERS WIFE OF THE LATE HENRY MARTYN ROGERS MISSIONARY PRIEST AT TRISTAN DA CUNHA AND FELLOW-WORKER WITH HIM ON THAT ISLAND WITH A MAP AND 24 ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON: GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD. RUSKIN OUSE, 40 MUSEUM STREET, W.C.1 Abstracted from Admiralty Chart No. 1769 and reduced. Agent Mr. J. D. Potter, 145, Minories, E.1. DEDICATED TO THE MEMBERS OF OUT LITTLE FLOCK ON THE ISLAND OF TRISTAN DA CUNHA HENRY MARTYN ROGERS In Memoriam HENRY MARTYN ROGERS Born February 22, 1879. Died May 14, 1926. "The rushing of the Atlantic waves is still in my ears, while I can still smell the kelp on the beach, and can see those eager, tear-stained faces pleading for our return—for my heart is ever there and I hope I may yet be able to return to the little island flock I love so well." HENRY MARTYN ROGERS, in a public lecture delivered shortly before his death. IN MEMORIAM THE service of Henry Martyn Rogers on behalf of the people of Tristan da Cunha has been a sacrifice throughout, and it has ended in the supreme sacrifice. He volunteered well knowing that there was the minimum of reward attaching to the work, and it afforded no means of provision for the future. He knew, too, that the funds available did not admit of adequate equipment or safeguard against those privations that were inevitable in life on a barren rock in the very centre of the South Atlantic Ocean and out of the way of all regular ships' traffic. -

The Lonely Crowd – Issue Four

the lonely crowd / spring the lonely crowd the lonely crowd new home of the short story Edited and Designed by John Lavin Advisory Editor Michou Burckett St. Laurent Front & Back Cover Photos by Jo Mazelis Frontispiece from ‘The Greystone’ by Seamus Sullivan Published by The Lonely Press, 2016 Printed in Wales by Gwasg Gomer Copyright The Lonely Crowd and its contributors, 2016 ISBN 978-0-9932368-3-9 The Lonely Crowd is an entirely self-funded enterprise. Please consider supporting us by subscribing to the magazine here www.thelonelycrowd.org/the-lonely-store If you would like to advertise in The Lonely Crowd please email [email protected] Please direct all other enquiries to [email protected] Visit our website for more new short fiction, poetry and photography www.thelonelycrowd.org Contents Liling's Escape Kate Hamer - 9 Three Poems Joe Dunthorne - 19 Woman Waiting at a Station Alan McMonagle - 22 Made You Look Valerie Sirr - 31 Three Poems Polly Atkin - 40 Crusades Marie Gethins - 46 Janet Norbury Charlie Hill - 62 Like the Dust Leila Segal - 65 Three Poems Zelda ChapPel - 72 Undertaker Bethany W. Pope - 76 The Ukrainian Girl Catherine McNamara - 85 The Sparkle of River Through the Trees Neil CamPbell - 96 Three Poems James Aust - 105 June 20: The Ratling Robert Minhinnick - 113 The Greystone Seamus Sullivan - 117 June 24: Razors Robert Minhinnick - 128 Point of Lay Siân Melangell Dafydd - 133 Two Poems Scarlett Sabet - 142 For You Are Julia C. G. Menon - 147 Looks Like Rain Susie Wild - 156 Two Poems Carol Lipszyc - 159 One and Only Girl Laura Windley - 169 Priest Giles Rees - 177 Three Poems Sarah James - 188 Villavicencio Iain Robinson - 192 Herr Munch Visits the Zoo Diana Powell - 206 Two Poems Katharine Stansfield - 214 The Last Minutes of BA Flight 465 Armel Dagorn - 217 Per Ardua Sergo Nigel Jarrett - 221 A Different River Pia Ghosh Roy - 230 Six Secrets of Ivy Samantha Wynne-Rhydderch - 239 About the Authors - 240 spring Three Poems Joe Dunthorne New lessons My thesis (self-funded) is: attractive people are hapPy. -

Rod Serling Papers, 1945-1969

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5489n8zx No online items Finding Aid for the Rod Serling papers, 1945-1969 Finding aid prepared by Processed by Simone Fujita in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Kelley Wolfe Bachli, 2010. Prior processing by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Rod Serling 1035 1 papers, 1945-1969 Descriptive Summary Title: Rod Serling papers Date (inclusive): 1945-1969 Collection number: 1035 Creator: Serling, Rod, 1924- Extent: 23 boxes (11.5 linear ft.) Abstract: Rodman Edward Serling (1924-1975) wrote teleplays, screenplays, and many of the scripts for The Twilight Zone (1959-65). He also won 6 Emmy awards. The collection consists of scripts for films and television, including scripts for Serling's television program, The Twilight Zone. Also includes correspondence and business records primarily from 1966-1968. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. -

Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism English, Department of January 1911 Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads John A. Lomax M.A. University of Texas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Lomax, John A. M.A., "Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads" (1911). University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism. 12. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. COWBOY SONGS AND OTHER FRONTIER BALLADS COLLECTED BY * * * What keeps the herd from running, JOHN A. LOMAX, M. A. THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS Stampeding far and wide? SHELDON FELLOW FOR THE INVESTIGATION 1)F AMERICAN BALLADS, The cowboy's long, low whistle, HARVARD UNIVERSITY And singing by their side. * * * WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY BARRETT WENDELL 'Aew moth STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY I9Il All rights reserved Copyright 1910 <to By STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY MR. THEODORE ROOSEVELT Set up lUld electrotyped. Published November, 1910 WHO WHILE PRESIDENT wAs NOT TOO BUSY TO Reprinted April, 1911 TURN ASIDE-CHEERFULLY AND EFFECTIVELY AND AID WORKERS IN THE FIELD OF AMERICAN BALLADRY, THIS VOLUME IS GRATEFULLY DEDICATED ~~~,. < dti ~ -&n ~7 e~ 0(" ~ ,_-..~'t'-~-L(? ~;r-w« u-~~' ,~' l~) ~ 'f" "UJ ":-'~_cr l:"0 ~fI."-.'~ CONTENTS ::(,.c.........04.._ ......_~·~C&-.