University of Nevada, Reno Between the Pit of Man's Fears and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry: Grades 7 & 8

1 Poetry: Grades 7 & 8 Barter Casey at the Bat The Creation The Crucifixion The Destruction of Sennacherib Do not go gentle into that good night From “Endymion,” Book I Forgetfulness The Highwayman The House on the Hill If The Listeners Love (III) The New Colossus No Coward Soul Is Mine One Art On His Blindness On Turning Ten Ozymandias Paul Revere's Ride The Road Goes Ever On (from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings) Sonnet Spring and Fall Stanzas th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 2 The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls The Village Blacksmith The World th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 3 Barter Sara Teasdale Life has loveliness to sell, All beautiful and splendid things, Blue waves whitened on a cliff, Soaring fire that sways and sings, And children's faces looking up Holding wonder in a cup. Life has loveliness to sell, Music like a curve of gold, Scent of pine trees in the rain, Eyes that love you, arms that hold, And for your spirit's still delight, Holy thoughts that star the night. Spend all you have for loveliness, Buy it and never count the cost; For one white singing hour of peace Count many a year of strife well lost, And for a breath of ecstasy Give all you have been, or could be. † th th South Texas Christian Schools Speech Meet 2019-2020 7 - 8 Grade Poetry 4 Casey at the Bat Ernest Lawrence Thayer The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day: The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play, And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same, A pall-like silence fell upon the patrons of the game. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

RAMSEY CAMPBELL INTERVIEWED RAMSEY CAMPBELL INTERVIEW ^By Brendan Ryder Page 13

ISSUE NO. 76 August 1992 ________ ISSN 0791-3966 RAMSEY CAMPBELL INTERVIEWED RAMSEY CAMPBELL INTERVIEW ^by Brendan Ryder page 13 THE TWILIGHT ZONE How to find your way around by Michael Cullen page 5 OUR SEMI-ANNUAL "MEGA" QUIZ It’s not just a quiz, it's the contents of page 11 MORPHING So how did Arnie turn into Michael Jackson? See on page 12 REGULAR FEATURES News 3 ISFA News 4 Letters 7 Meeting report 8 Movies 9 Videos 10 Book Reviews 15 Comics 18 Drabbles 19 PUBLISHED BY Wc welcome unsolicited manuscripts on the basis that the THE IRISH SCIENCE FICTION ISFA is poor, and if wc don’t actually pay contributors it ASSOCIATION doesn’t mean wc don’t appreciate them. So send us your news. Send us your opinions. Send us your doodles. Send 30, BEVERLY DOWNS us your shorts. But wash ’em first. KNOCKLYON ROAD Take that old dusty Royal out of the wardrobe and type it, TEMPLEOGUE, DUBLIN 16 if you can. If you can’t, well, it’s not the end of the world. FURTHER INFORMATION NOTE: OPINIONS EXPRESSED ARE NOT THOSE OF FROM THIS ADDRESS OR THE ISFA, EXCEPT WHERE STATED AS SUCH PHONE 934712 2 ISFA Newsletter August 1992 NEWS Crypt Creator Dies Wiliam M Gaines, publisher of Mad maga zine and the EC comics line which included Rings, No Strings Weird Science, Tales from the Crypt, and As part of the Galway Arts Festival which ran The Vault of Horror, died in Manhattan in from 15-26 July, the Canadian Theatre Sans June, at the age of 70. -

The Twilight Zone: Landmark Television Derek Kompare

The Twilight Zone: Landmark Television Derek Kompare From the original edition of How to Watch Television published in 2013 by New York University Press Edited by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell Accessed at nyupress.org/9781479898817 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND). 32 The Twilight Zone Landmark Television Derek Kompare Abstract: Few programs in television history are as iconic as Te Twilight Zone, which lingers in cultural memory as one of the medium’s most distinctive aesthetic and cultural peaks. Derek Kompare examines the show’s signature style and voice of its emblematic creator Rod Serling, exploring how the program’s legacy lives on today across genres and eras. As with any other art form, television history is in large part an assemblage of exemplary works. Industrial practices, cultural infuences, and social contexts are certainly primary points of media histories, but these factors are most ofen recognized and analyzed in the form of individual texts: moments when par- ticular forces temporarily converge in unique combinations, which subsequently function as historical milestones. Regardless of a perceived historical trajectory towards or away from “progress,” certain programs have come to represent the confuence of key variables at particular moments: I Love Lucy (CBS, 1951–1957) revolutionized sitcom production; Monday Night Football (ABC, 1970–2005; ESPN, 2005–present) supercharged the symbiotic relationship of sports and tele- vision; Hill Street Blues (NBC, 1981–1987) introduced the “quality” serial drama to primetime. Te Twilight Zone (CBS, 1959–1964) is an anomalous case, simultaneously one of the most important and least representative of such milestones. -

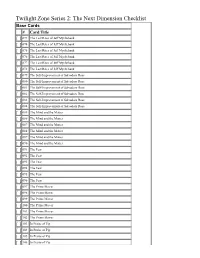

Twilight Zone Series 2: the Next Dimension Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 2: The Next Dimension Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 073 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 074 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 075 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 076 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 077 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 078 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 079 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 080 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 081 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 082 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 083 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 084 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 085 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 086 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 087 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 088 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 089 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 090 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 091 The Fear [ ] 092 The Fear [ ] 093 The Fear [ ] 094 The Fear [ ] 095 The Fear [ ] 096 The Fear [ ] 097 The Prime Mover [ ] 098 The Prime Mover [ ] 099 The Prime Mover [ ] 100 The Prime Mover [ ] 101 The Prime Mover [ ] 102 The Prime Mover [ ] 103 In Praise of Pip [ ] 104 In Praise of Pip [ ] 105 In Praise of Pip [ ] 106 In Praise of Pip [ ] 107 In Praise of Pip [ ] 108 In Praise of Pip [ ] 109 Nick of Time [ ] 110 Nick of Time [ ] 111 Nick of Time [ ] 112 Nick of Time [ ] 113 Nick of Time [ ] 114 Nick of Time [ ] 115 Shadow Play [ ] 116 Shadow Play [ ] 117 Shadow Play [ ] 118 Shadow Play [ ] 119 Shadow Play [ ] 120 Shadow Play [ ] 121 Four O'Clock [ ] 122 Four O'Clock [ ] 123 Four O'Clock [ ] 124 Four O'Clock [ ] 125 Four O'Clock [ ] 126 Four -

The Lonely Society? Contents

The Lonely Society? Contents Acknowledgements 02 Methods 03 Introduction 03 Chapter 1 Are we getting lonelier? 09 Chapter 2 Who is affected by loneliness? 14 Chapter 3 The Mental Health Foundation survey 21 Chapter 4 What can be done about loneliness? 24 Chapter 5 Conclusion and recommendations 33 1 The Lonely Society Acknowledgements Author: Jo Griffin With thanks to colleagues at the Mental Health Foundation, including Andrew McCulloch, Fran Gorman, Simon Lawton-Smith, Eva Cyhlarova, Dan Robotham, Toby Williamson, Simon Loveland and Gillian McEwan. The Mental Health Foundation would like to thank: Barbara McIntosh, Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities Craig Weakes, Project Director, Back to Life (run by Timebank) Ed Halliwell, Health Writer, London Emma Southgate, Southwark Circle Glen Gibson, Psychotherapist, Camden, London Jacqueline Olds, Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard University Jeremy Mulcaire, Mental Health Services, Ealing, London Martina Philips, Home Start Malcolm Bird, Men in Sheds, Age Concern Cheshire Opinium Research LLP Professor David Morris, National Social Inclusion Programme at the Institute for Mental Health in England Sally Russell, Director, Netmums.com We would especially like to thank all those who gave their time to be interviewed about their experiences of loneliness. 2 Introduction Methods A range of research methods were used to compile the data for this report, including: • a rapid appraisal of existing literature on loneliness. For the purpose of this report an exhaustive academic literature review was not commissioned; • a survey completed by a nationally representative, quota-controlled sample of 2,256 people carried out by Opinium Research LLP; and • site visits and interviews with stakeholders, including mental health professionals and organisations that provide advice, guidance and services to the general public as well as those at risk of isolation and loneliness. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

The Machine Gun Hand: Robots, Performance, and American Ideology in the Twentieth Century

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2017 The aM chine Gun Hand: Robots, Performance, and American Ideology in the Twentieth Century Benjamin Michael Phelan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Phelan, Benjamin Michael, "The aM chine Gun Hand: Robots, Performance, and American Ideology in the Twentieth Century" (2017). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4469. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4469 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE MACHINE GUN HAND: ROBOTS, PERFORMANCE, AND AMERICAN IDEOLOGY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Theatre by Benjamin Michael Phelan B.A., Brigham Young University, 2008 August 2017 Acknowledgments First, I must thank my major professor, friend, and advisor, Alan Sikes. Without his insightful comments throughout the years, this dissertation would have never gained much shape or inertia. I cannot thank him enough for his love and support and for the hours of meetings at Garden District Coffee or over the phone, helping me formulate my ideas into concrete chapters. This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous support of numerous faculty at Louisiana State University. -

VIVA LA VOZ Committee Members Will Not Seek Re-Election

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 THURSDAY, AUGUST 22, 2019 DEALS OF THE Lynn eld will meet Western Avenue site$DAY$ about rail trail design slated for townhousesPG. 3 By Thor Jourgensen meeting, tentatively scheduled for 7 p.m. By Gayla Cawley and everyone felt the best use for that ITEM STAFF in the middle school. ITEM STAFF site would be residential,” said James “Based on the ballot referendum last Cowdell, EDIC/Lynn’sDEALS executive direc- LYNNFIELD — For the rst time in year, it should be fairly well attended,” LYNN — A $200,000 clean-up has tor. “We’re really happy that we were ve years the town is on target to host a said Crawford. turned a contaminated lot on Western able to clean up the siteOF and THE now turn it special town meeting with Sept. 26 the The last special town meeting was held Avenue into a place for new homes. into a residential project$ that everyone$ tentative date for debating $348,000 in in June 2014 to discuss the fate of the Economic Development and Industrial can be proud of.” DAY rail trail design spending. Centre Farm property in the town cen- Corp. of Lynn (EDIC/Lynn), the proper- If the development getsPG. the 3green light, Almost 300 residents signed a citizen ter. ty’s owner which last housed a gas sta- when completed, it would result in 16 petition circulated by the Friends of Crawford said the design estimate sub- tion 20 years ago, will soon enter into new townhouses and eight single-family Lynn eld Rail Trail to put trail design mitted in the petition mirrors trail de- an agreement with Lynn Housing Au- homes in the neighborhood. -

TZPT124 Five Characters

This is the first transcript of The Twilight Zone Podcast for hearing impaired fans of The Twilight Zone. Although perhaps “transcript” isn't quite the right term, as this document is actually the notes I make prior to recording the show, which I then read from. Instead of just deleting them each time as I have done for 100 plus episodes of The Twilight Zone Podcast, I hope they will be of some enjoyment to hearing impaired fans of the show. Please bear in mind that these notes are made for me to riff on and read from, so the style and cadence may be different from if they were written for an article, and much as I've tried to clean them up they may be rough round the edges in places. My apologies that I didn't do this sooner, but I hope you enjoy them now. Best Wishes – Tom Elliot Five Characters in Search of an Exit Introduction: Where are we? What are we? Who are we? Three questions that we've probably all asked at some point in our lives, perhaps not in the plural sense, but certainly in the singular. Where am I? What am I? Who am I? Why am I here? What am I doing with my life? Who am I supposed to be? We're seconds into this Twilight Zone Podcast and already things are getting kind of heavy. But in this case, how can we not be? It's always a bit of a balancing act with this show. The Twilight Zone has many levels. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

Terra Nova, an Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience

Syracuse University SURFACE S.I. Newhouse School of Public Media Studies - Theses Communications 8-2012 Terra Nova, An Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ms_thesis Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Terra Nova, An Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience" (2012). Media Studies - Theses. 5. https://surface.syr.edu/ms_thesis/5 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Studies - Theses by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When it aired in Fall 2011 on Fox, Terra Nova was an experiment in creating a cult television program that appealed to a mass audience. This thesis is a case study of that experiment. I conclude that the show failed because of its attempts to maintain the sophistication, complexity and innovative nature of the cult genre while simultaneously employing an overly simplistic narrative structure that resembles that of mass audience programming. Terra Nova was unique in its transmedia approach to marketing and storytelling, its advanced special effects, and its dystopian speculative fiction premise. Terra Nova’s narrative, on the other hand, presented a nostalgically simple moralistic landscape that upheld old-fashioned ideologies and felt oddly retro to the modern SF TV audience. Terra Nova’s failure suggests that a cult show made for this type of broad audience is impossible.