The Machine Gun Hand: Robots, Performance, and American Ideology in the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Screendollars About Films, the Film Industry No

For Exhibitors July 13, 2020 Screendollars About Films, the Film Industry No. 125 Newsletter and Cinema Advertising The Good, The The Battle of The Big Gundown Il Gatto A Nove Novecento Days of Heaven The Thing Bad and The Ugly Algiers (1968) Code (1976) (1978) (1982) (1967) (1966) (1971) We celebrate the work of famous film composer Ennio Morricone, who passed away on last week on July 6th at the age of 91. Morricone’s career spanned almost 70 years and included groundbreadking scores for films of many genres. His compositions incorporated music performed by orchestras and ensembles of all sizes, playing many different instruments and even incorporating seemingly non-instrumental sounds such as the famous coyote-like howling in the opening of the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. These films are a list of the 10 most mind- blowing film scores, compiled by Randall Roberts of the LA Times. The Mission The The H8tful Eight "I really like conducting my music in concerts because I'm convinced it's not just (1986) Untouchables (2015) for films; it has its own life. It can live far away from the images of the movie." (1987) - Ennio Morricone Notable Industry News and Commentary (7/6-12) Screen Engine Launches Online Word-of-Mouth Screening Platform Amid Theater Closures (Hollywood Reporter) Theatre closures have blocked film studios from conducting pre-release, in-theatre screenings of their upcoming films. These focus group screenings have been an essential tool used by studios to evaluate audience response to upcoming films and TV series and to generate pre-release press coverage and buzz on social media. -

A Philosophical Perspective on Constructing Active Masculinities

Feminist Philosophy Quarterly Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 2 Care and the Self: A Philosophical Perspective on Constructing Active Masculinities Iva Apostolova Dominican University College, [email protected] Elaina Gauthier-Mamaril Aberdeen University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Apostolova, Iva and Elaina Gauthier-Mamaril. "Care and the Self: A Philosophical Perspective on Constructing Active Masculinities." Feminist Philosophy Quarterly4, (1). Article 2. Apostolova and Gauthier-Mamaril: Care and the Self: Caring Masculinities Care and the Self: A Philosophical Perspective on Constructing Active Masculinities Iva Apostolova and Élaina Gauthier-Mamaril Abstract Our paper focuses on the philosophical perspective of constructing active (as opposed to reactive) caring masculine agencies in the contemporary feminist discourse. Since contemporary feminisms are not simply anti-essentialist but, more importantly, polyphonic, we believe that it is far more appropriate to talk about ‘masculinities’ as opposed to ‘masculinity.’ We are proposing a revised understanding of the self in which the self is not defined primarily in the dichotomous, categorical one-other relationship. We use Paul Ricoeur’s anthropology to describe the self as relational, as well as Joan Tronto’s recent perspective on care, which fits well with a Ricoeurian reconstruction of the self. We also engage with Raewyn Connell’s discourse on masculinity and, more specifically, hegemonic masculinity. By using ‘caring masculine agencies’ as an alternative to ‘masculinity as reactive anti-femininity,’ we are proposing a paradigm shift that hopefully is flexible enough to respect the dynamism inherent to any act of gender- identification. Keywords: hegemonic masculinities, reactive masculinities, active/caring masculinities, ethics of care, relational self Our research aims at opening a new narrative space for masculinity within a feminist context. -

Cassie Jaye's Red Pill Too Truthful for Feminists to Tolerate

Cassie Jaye’s Red Pill too truthful for feminists to tolerate Cassie Jaye at the world premiere of The Red Pill earlier this month. Picture: Ian Stroud Bettina Arndt, The Australian, 12:00AM October 29, 2016 “The Red Pill: The movie about men that feminists didn’t want you to see.” This was the provocative headline that ran in Britain’s The Telegraph last November, a teaser for a documentary made by a feminist filmmaker who planned to take on men’s rights activists but was won over and crossed to the dark side to take up their cause. Despite a ferocious campaign to stop the movie being made, it’s finally been released and the Australian screening was due next week in Melbourne. However the gender warriors have struck again, using a change.com petition to persuade Palace Cinemas to cancel the booking. Palace took the decision after being told the movie would offend many in its core audience but by yesterday 8000 had signed petitions protesting the ban. Organisers are now scrambling to find another venue. Clearly this documentary has the feminists very worried — with good reason. Cassie Jaye is an articulate, 29-year-old blonde whose previous movies on gay marriage and abstinence education won multiple awards. But then she decided to interview leaders of the Men’s Rights Movement for a documentary she was planning about rape culture on American campuses. As a committed feminist, Jaye expected to be unimpressed by these renowned hate-filled misogynists, but to her surprise she was exposed to a whole range of issues she came to see as unfairly stacked against men and boys. -

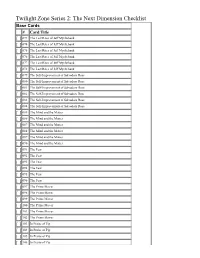

Twilight Zone Series 2: the Next Dimension Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 2: The Next Dimension Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 073 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 074 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 075 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 076 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 077 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 078 The Last Rites of Jeff Myrltebank [ ] 079 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 080 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 081 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 082 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 083 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 084 The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Rose [ ] 085 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 086 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 087 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 088 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 089 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 090 The Mind and the Matter [ ] 091 The Fear [ ] 092 The Fear [ ] 093 The Fear [ ] 094 The Fear [ ] 095 The Fear [ ] 096 The Fear [ ] 097 The Prime Mover [ ] 098 The Prime Mover [ ] 099 The Prime Mover [ ] 100 The Prime Mover [ ] 101 The Prime Mover [ ] 102 The Prime Mover [ ] 103 In Praise of Pip [ ] 104 In Praise of Pip [ ] 105 In Praise of Pip [ ] 106 In Praise of Pip [ ] 107 In Praise of Pip [ ] 108 In Praise of Pip [ ] 109 Nick of Time [ ] 110 Nick of Time [ ] 111 Nick of Time [ ] 112 Nick of Time [ ] 113 Nick of Time [ ] 114 Nick of Time [ ] 115 Shadow Play [ ] 116 Shadow Play [ ] 117 Shadow Play [ ] 118 Shadow Play [ ] 119 Shadow Play [ ] 120 Shadow Play [ ] 121 Four O'Clock [ ] 122 Four O'Clock [ ] 123 Four O'Clock [ ] 124 Four O'Clock [ ] 125 Four O'Clock [ ] 126 Four -

AUDIENCE GUIDE PRODUCTION SPONSOR Th February 25 – ® March 18Th, 2018 TABLE of CONTENTS

BY JORDAN HARRISON DIRECTED BY LISA RUBIN AUDIENCE GUIDE PRODUCTION SPONSOR th February 25 – ® March 18th, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 PRODUCTION CREDITS AUDIENCE ETIQUETTE 4 ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT 5 ABOUT THE DIRECTOR 6 PLAY SYNOPSIS 7 A BRIEF LOOK AT AI - THE FOUNDATION OF NEW TECHNOLOGY - ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN MEDICINE - MACHINE-BEINGS AND ELDER CARE 9 MONTREAL'S AI BOOM 11 ETHICAL ISSUES RELATED TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE 12 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 13 ABOUT THE SEGAL CENTRE FOR PERFORMING ARTS ABOUT THIS AUDIENCE GUIDE This audience guide is written, compiled and edited by Patrick Lloyd Brennan thanks to the generous support of Richter (Inclusivity and Engagement Partner) and the Mitzi & Mel Dobrin Family Foundation. This audience guide is meant to enhance and deepen our audience’s experience and understanding. All content is intended for educational purposes only. To reserve group tickets at a reduced rate, or for questions, comments, citations or references, please contact Patrick Lloyd Brennan: 514 739 2301 ext. 8360 [email protected] THE SEGAL CENTRE 5170 CÔTE-STE-CATHERINE MONTREAL, QUÉBEC, H3W 1M7 | SEGALCENTRE.ORG 2 FOR PERFORMING ARTS PRODUCTION CREDITS A SEGAL CENTRE PRODUCTION Written by JORDAN HARRISON Directed by LISA RUBIN CAST MARJORIE Clare Coulter JON Tyrone Benskin WALTER Eloi ArchamBaudoin and Ellen David as TESS CREATIVE TEAM ARTISTIC ASSOCIATE / ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Caitlin Murphy SET DESIGNER John C. Dinning COSTUME DESIGNER Louise Bourret LIGHTING DESIGNER Tim Rodrigues MUSIC Christian Thomas STAGE MANAGER Sarah-Marie Langlois ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER Birdie Gregor The Segal Theatre is a member of the Professional Association of Canadian Theatres and engages, under the terms of the Canadian Theatre Agreement, professional artists who are members of Canadian Actors’ Equity Association. -

The Last Remnant Xbox 360 Iso Download Region Free the Last Remnant

the last remnant xbox 360 iso download region free The Last Remnant. In ancient times, mysterious artifacts referred to as Remnants were discovered all over the world. People used these objects for their awesome powers — a choice that eventually began to cause a rift in the world's balance. Equality was replaced by those who ruled and those who were ruled over. War was inevitable. A thousand years later is when this story begins. Rush lives with his sister Irina on secluded Eulam Island, far from the power struggles for Remnants that are occurring back on the mainland. However, this peaceful life is shattered when his sister is suddenly kidnapped by a mysterious group of soldiers right before his eyes. He immediately sets off after them, unaware of the evils of the outside world but determined to find his sister at any cost. The Last Remnant. The first things that'll strike you about The Last Remnant, after its perplexingly long install process on Steam has completed, is that the menu system is a confusing mess. All the information is there, but navigating is a pain in the posterior. I even resorted to plugging in an Xbox 360 pad, which promptly failed to work. Finally I found all the options I wanted and there was an intriguing nugget hidden away in the clutter: you can play this JRPG in Japanese with English subtitles. The plot of The Last Remnant runs thus: you play Rush Sykes, whose sister has been spirited off by some ne'er-do-wells, leaving only her magic talisman behind. -

The Divergent Archive and Androcentric Counterpublics: Public Rhetorics, Memory, and Archives

THE DIVERGENT ARCHIVE AND ANDROCENTRIC COUNTERPUBLICS: PUBLIC RHETORICS, MEMORY, AND ARCHIVES BY EVIN SCOTT GROUNDWATER DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kelly Ritter, Chair Associate Professor Peter Mortensen Assistant Professor John Gallagher Associate Professor Jessica Enoch, University of Maryland ii ABSTRACT As a field, Writing Studies has long been concerned with the rhetorical representation of both dominant and marginalized groups. However, rhetorical theory on publics and counterpublics tends not to articulate how groups persuade others of their status as mainstream or marginal. Scholars of public/counterpublic theory have not yet adequately examined the mechanisms through which rhetorical resources play a role in reinforcing and/or dispelling public perceptions of dominance or marginalization. My dissertation argues many counterpublics locate and convince others of their subject status through the development of rhetorical resources. I contend counterpublics create and curate a diffuse system of archives, which I refer to as “divergent archives.” These divergent archives often lack institutional backing, rigor, and may be primarily composed of ephemera. Drawing from a variety of archival materials both within and outside institutionally maintained archives, I explore how counterpublics perceiving themselves as marginalized construct archives of their own as a way to transmit collective memories reifying their nondominant status. I do so through a case study that has generally been overlooked in Writing Studies: a collection of men’s rights movements which imagine themselves to be marginalized, despite their generally hegemonic positions. -

Religion As a Role: Decoding Performances of Mormonism in the Contemporary United States

RELIGION AS A ROLE: DECODING PERFORMANCES OF MORMONISM IN THE CONTEMPORARY UNITED STATES Lauren Zawistowski McCool A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Dr. Scott Magelssen, Advisor Dr. Jonathan Chambers Dr. Lesa Lockford © 2012 Lauren Zawistowski McCool All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Scott Magelssen, Advisor Although Mormons have been featured as characters in American media since the nineteenth century, the study of the performance of the Mormon religion has received limited attention. As Mormonism (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) continues to appear as an ever-growing topic of interest in American media, there is a gap in discourse that addresses the implications of performances of Mormon beliefs and lifestyles as performed by both members of the Church and non-believers. In this thesis, I closely examine HBO’s Big Love television series, the LDS Church’s “I Am a Mormon” media campaign, Mormon “Mommy Blogs” and the personal performance of Mormons in everyday life. By analyzing these performances through the lenses of Stuart Hall’s theories of encoding/decoding, Benedict Anderson’s writings on imagined communities, and H. L. Goodall’s methodology for the new ethnography the aim of this thesis is to fill in some small way this discursive and scholarly gap. The analysis of performances of the Mormon belief system through these lenses provides an insight into how the media teaches and shapes its audience’s ideologies through performance. iv For Caity and Emily. -

Orson Scott Card's <I>Ender's Game</I>

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Department of English, Literature, and Modern English Seminar Capstone Research Papers Languages 4-15-2013 The eH roic Fallacy: Orson Scott aC rd’s Ender’s Game and the Young Adult Reader Shawn L. Buice Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ english_seminar_capstone Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Buice, Shawn L., "The eH roic Fallacy: Orson Scott aC rd’s Ender’s Game and the Young Adult Reader" (2013). English Seminar Capstone Research Papers. 17. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/english_seminar_capstone/17 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Seminar Capstone Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shawn Buice Dr. Deardorff Senior Seminar 15 April 2013 The Heroic Fallacy: Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game and the Young Adult Reader Buice 1 This paper was an opportunity to connect my education as a student of literature with my past experience as a reader. I was always more comfortable reading young adult, science fiction or fantasy novels, perhaps because this is what I read growing up. Interestingly, a trend of the past decade in British literary criticism has been to study crossover literature. This includes books that have been widely read by both adults and children. The case for studying adolescent fiction intersects with studies of crossover fiction. Individuals for whom reading was a formative part of their upbringing, by taking a closer look at adolescent fiction can peer into the past and try to understand the events and experiences that shaped the yet unmolded identity. -

Downloaded,” and Galen Tryol Has a Son, Nicholas, with His Human Wife, Cally, When the Couple Lives on the Planet New Caprica

DISTRIBUTION AGREEMENT In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in who or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation ____________________________________ July 16, 2014__________ Sarah Toton Date From Mechanical Men to Cybernetic Skin-Jobs: A History of Robots in American Popular Culture By Sarah Toton Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts ________________________________________________ Cristine Levenduski, Ph.D. Co-Chair ________________________________________________ Kevin Corrigan, Ph.D. Co-Chair ________________________________________________ Ted Friedman, Ph.D. Outside Co-Chair ________________________________________________ Karla Oeler, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: ________________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies _______________________ Date ! From Mechanical Men to Cybernetic Skin-Jobs: A History of Robots in American Popular Culture -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

Oda Nobunaga in Japanese Videogames the Case of Nobunaga’S Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013)

Trabajo Fin de Máster Oda Nobunaga en los videojuegos japoneses El caso de Nobunaga’s Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013) Oda Nobunaga in Japanese videogames The case of Nobunaga’s Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013) Autora Claudia Bonillo Fernández Directoras Elena Barlés Báguena Amparo Martínez Herranz Facultad de Filosofía y Letras/ Departamento de Historia del Arte Curso 2017-2018 2 ÍNDICE I. PRESENTACIÓN DEL TRABAJO .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Delimitación del tema y causas de su elección ..................................................................................................... 3 2. Estado de la cuestión ............................................................................................................................................. 5 3. Objetivos del trabajo ............................................................................................................................................. 9 4. Metodología .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 4.1. Búsqueda, recopilación, lectura y análisis de material bibliográfico ........................................................... 10 4.2. Búsqueda, recopilación, lectura y análisis de material documental ............................................................. 11 4.3. Trabajo de campo ........................................................................................................................................