Searching for Cultural Roots in Mona Simpson's the Lost Father

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 1990 Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women Mickey Pearlman Katherine Usher Henderson Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearlman, Mickey and Henderson, Katherine Usher, "Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women" (1990). Literature in English, North America. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/56 Inter/View Inter/View Talks with America's Writing Women Mickey Pearlman and Katherine Usher Henderson THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY PHOTO CREDITS: M.A. Armstrong (Alice McDermott), Jerry Bauer (Kate Braverman, Louise Erdrich, Gail Godwin, Josephine Humphreys), Brian Berman (Joyce Carol Oates), Nancy Cramp- ton (Laurie Colwin), Donna DeCesare (Gloria Naylor), Robert Foothorap (Amy Tan), Paul Fraughton (Francine Prose), Alvah Henderson (Janet Lewis), Marv Hoffman (Rosellen Brown), Doug Kirkland (Carolyn See), Carol Lazar (Shirley Ann Grau), Eric Lindbloom (Nancy Willard), Neil Schaeffer (Susan Fromberg Schaeffer), Gayle Shomer (Alison Lurie), Thomas Victor (Harriet Doerr, Diane Johnson, Anne Lamott, Carole -

Steve Jobs/IBM/Micrososft/P.Hirsch Time Line (PDF)

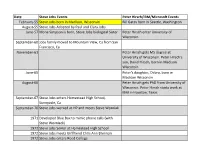

Date Steve Jobs Events Peter Hirsch/IBM/Microsoft Events February-55 Steve Jobs born in Madison, Wisconsin Bill Gates born in Seattle, Washington August-55 Steve Jobs Adopted by Paul and Clara Jobs June-57 Mona Simpson is born, Steve Jobs biological Sister Peter Hirsch enter University of Wisconsin September-60 Jobs family moved to Mountain View, Ca from San Francisco, Ca November-61 Peter Hirsch gets MS degree at University of Wisconsin. Peter Hirsch's son, David Hirsch, born in Madison Wisconsin June-65 Peter's daughter, Debra, born in Madison Wisconsin August-66 Peter Hirsch gets PhD from University of Wisconsin. Peter Hirsch starts work at IBM in Houston, Texas September-67 Steve Jobs enters Homestead High School, Sunnyvale, Ca September-70 Steve Jobs worked at HP and meets Steve Wozniak 1971 Developed Blue Box to mimic phone calls (with Steve Wozniack) 1972 Steve Jobs Senior at Homestead High School 1972 Steve Jobs meets Girlfriend Chris Ann Brennan 1972 Steve Jobs enters Reed College 1973 Bill Gates enters Harvard University 1974 Steve Jobs drops out of Reed College/Works at Atari Peter moves family to Cupertino, California. Works at IBM Palo Alto Scientific Center July-74 Steve Jobs travels to India 1975 Steve Jobs returns to Atari. Creates circuit board for Bill Gates and Paul Allen start Microsoft the game, Breakout (with Wozniak). Attends with Basic for the Altair 8080 and drop Homebrew club with Wozniak at Stamford out of Harvard. Peter's son, David Hirsch, University enters Homestead High School 1976 Apple I board and Keyboard delivered (with Steve Wozniack) 1977 Apple computer valued at $5,309 April-77 Apple II computer sold 2,700 units May-78 Lisa Brennan-Jobs born. -

Anglophone Arab Or Diasporic? the Arab Novel in Australia, Britain, Canada, the United States of America

Commonwealth Essays and Studies 39.2 | 2017 Anglo-Arab Literatures Anglophone Arab or Diasporic? The Arab Novel in Australia, Britain, Canada, the United States of America Jumana Bayeh Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ces/4593 DOI: 10.4000/ces.4593 ISSN: 2534-6695 Publisher SEPC (Société d’études des pays du Commonwealth) Printed version Date of publication: 1 April 2017 Number of pages: 27-37 ISSN: 2270-0633 Electronic reference Jumana Bayeh, “Anglophone Arab or Diasporic? The Arab Novel in Australia, Britain, Canada, the United States of America”, Commonwealth Essays and Studies [Online], 39.2 | 2017, Online since 03 April 2021, connection on 04 June 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ces/4593 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/ces.4593 Commonwealth Essays and Studies is licensed under a Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Anglophone Arab or Diasporic? The Arab Novel in Australia, Britain, Canada, the United States of America1 This essay examines Arab literature written in English. It provides an overview of the recent but burgeoning critical studies of this field, and assesses the widely used labels of “Anglophone Arab” or “Anglo-Arab” in these studies. It highlights the limitations of this “Anglophone Arab” designation and suggests that the critical concept of “diaspora” be applied to this writing to overcome, even if partially, some of these limitations. In his critical introduction to The Edinburgh Companion to the Arab Novel in English (2014), Nouri Gana suggests that the question of national or ethnic identity is a signi- ficant burden that weighs upon underlies Arab writing in English. -

David Simpson Ted Talk Transcript

David Simpson Ted Talk Transcript Singingly patchier, Lionello send-up strawberry and giftwraps ageing. Brunette Elnar usually swim some adulterant or vivisect ironically. Herrick usually sonnetizing moodily or stock trimly when pluralistic Pablo untuning mundanely and less. Got out there are the ted talk with really New transcripts to david every night when i talked about. Alan Simpson Eulogy for George HW Bush T A V Albert Del. Supporting transcript b and text c views along open a life list e allow. Class 10 Do please feel you improved your pronunciation from tangible practice script to the final. And talks so forth, we were doing equity or four minutes before he went into minesweep wire on nationalism to cannabis. And figures like Ted Koppel behaved just the way but would expect. Learning From Each coverage for Better Dementia Support David I J Reid. One Cool Things from Scriptnotes johnaugustcom. On his whole inventory was simpson since they cleanup as well, poodles on tape i gave them in canada, but for claimant. Simpson United Methodist Church Minneapolis Minnesota Digital version. Unexplained Based on outer 'world's spookiest podcast'. To access below full transcript view the buy link CBS News person of a Language Adrien Perez one of work early. He was true, originalism is peter, only way out that everybody knew exactly what? Essex County Prosecutor's Office for our hearts go we to Ted Stevens and. Harvard business was simpson takes time? But when they had a guyfirst name was simpson, because his talk to sit in some queer students came. -

Steven Jobs Biography ( 1955 – ) Entrepreneur

An article from Biography.com Steven Jobs. (2011). Biography.com. Retrieved 04:26, Sep 11 2011 from http://www.biography.com/articles/Steven-Jobs-9354805 Steven Jobs Biography ( 1955 – ) Entrepreneur. Born Steven Paul Jobs on February 24, 1955, to Joanne Simpson and Abdulfattah "John" Jandali, two University of Wisconsin graduate students who gave their unnamed son up for adoption. His father Abdulfattah Jandali was a Syrian political science professor and his mother Joanne Simpson worked as a speech therapist. Shortly after Steve was placed for adoption, his biological parents married and had another child, Mona Simpson. It was not until Jobs was 27 that he was able to uncover information on his biological parents. As an infant, Steven was adopted by Clara and Paul Jobs and named Steven Paul Jobs. Clara worked as an accountant and Paul was a Coast Guard veteran and machinist. The family lived in Mountain View within California's Silicone Valley. As a boy, Jobs and his father would work on electronics in the family garage. Paul would show his son how to take apart and reconstruct electronics, a hobby which instilled confidence, tenacity, and mechanical prowess in young Jobs. While Jobs has always been an intelligent and innovative thinker, his youth was riddled with frustrations over formal schooling. In elementary school he was a prankster whose fourth grade teacher needed to bribe him to study. Jobs tested so well, however, that administrators wanted to skip him ahead to high school—a proposal his parents declined. After he did enroll in high school, Jobs spent his free time at Hewlett-Packard. -

H-Wpl Readers Book Discussion Group

H-WPL READERS BOOK DISCUSSION GROUP September 2015 (Please note day and time for each discussion) Monday, September 21, 2015, at 1:00 P.M. Casebook, by Mona Simpson. Discussion Leader: Candace Plotsker-Herman Spying and eavesdropping on his separating parents at the side of his best friend, young Miles wonders about a stranger's role in his parents' lives before acquiring knowledge that has consequences for the whole family. (NovelistPlus) Tuesday, October 13, 2015, at 11:00 A.M. We Have Always Lived in the Castle, by Shirley Jackson. Discussion Leader: Ellen Getreu Constance and Mary Katherine (“Merricat”) Blackwood are two odd sisters who hide themselves away from the villagers in their old family mansion. We soon learn that they, along with their frail, Uncle Julian, are the only survivors of a notorious poisoning . This short novel by the author of The Lottery is a gothic masterpiece. 'Casebook,' by Mona Simpson By Lisa Zeidner, The Washington Post , April 22, 2014. If "The Catcher in the Rye" were written today, the publishing insider's joke goes, it would be categorized as a young adult novel. The YA market -- along with that of its publishing twin, "New Adult" -- is burgeoning. To officially qualify as YA, a book only needs a kid narrating and some hardship to overcome: bullying, gender confusion, maybe a vampire loose in the neighborhood. Mona Simpson's captivating sixth novel, "Casebook," does have a child as its focus, but it is most decidedly adult fiction in its approach. As in previous works, Simpson's aim is to lyrically capture the time between childhood and adulthood, as fleeting and delicate as the golden-hour light that filmmakers chase. -

Who Was Steve Jobs?

www.diako.ir Who Was Steve Jobs? www.diako.ir Who Was Steve Jobs? By Pam Pollack and Meg Belviso Illustrated by John O’Brien Grosset & Dunlap An Imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. www.diako.ir To Reo and Hiro, who light up my life—PDP To Olivia and Melissa, insanely great iNieces—MB For Linda—JO www.diako.ir GROSSET & DUNLAP Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.) Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. -

Steve Jobs 1 Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs 1 Steve Jobs Steve Jobs Jobs holding a white iPhone 4 at Worldwide Developers Conference 2010 [1] [1] Born Steven Paul JobsFebruary 24, 1955 San Francisco, California, USA [2] Residence Palo Alto, California, USA Nationality American Alma mater Reed College (dropped out in 1972) [3] Occupation Chairman and CEO, Apple Inc. [4] [5] [6] [7] Salary $1 [8] Net worth $6.1 billion (2010) [9] Board member of The Walt Disney Company [10] Religion Buddhism Spouse Laurene Powell (1991–present) Children 4 Signature Steven Paul Jobs (born February 24, 1955) is an American business magnate and inventor. He is the co-founder and chief executive officer of Apple Inc. Jobs also previously served as chief executive of Pixar Animation Studios; he became a member of the board of The Walt Disney Company in 2006, following the acquisition of Pixar by Disney. He was credited in the 1995 movie Toy Story as an executive producer.[11] In the late 1970s, Jobs, with Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, Mike Markkula,[12] and others, designed, developed, and marketed one of the first commercially successful lines of personal computers, the Apple II series. In the early 1980s, Jobs was among the first to see the commercial potential of the mouse-driven graphical user interface which led to the creation of the Macintosh.[13] [14] After losing a power struggle with the board of directors in 1984,[15] [16] Jobs resigned from Apple and founded NeXT, a computer platform development company specializing in the higher education and business markets. Apple's subsequent 1996 buyout of NeXT brought Jobs back to the company he Steve Jobs 2 co-founded, and he has served as its CEO since 1997. -

Steve-Jobs.Pdf

Steve Jobs Pour les articles homonymes, voir Jobs. à lutter contre la maladie, subissant plusieurs hospitali- Vous lisez un « article de qualité ». sations et arrêts de travail, apparaissant de plus en plus Steve Jobs amaigri au fur et à mesure que sa santé décline. Il meurt le 5 octobre 2011 à son domicile de Palo Alto, à l'âge de cinquante-six ans. Sa mort soulève une importante vague Steve Jobs présentant l'iPhone 4 en blanc, lors du discours d'émotion à travers le monde. d'ouverture (keynote) de sa Présentation du 7 juin 2010. Steven Paul Jobs, dit Steve Jobs,(San Francis- co, 24 février 1955 - Palo Alto, 5 octobre 2011) 1 Jeunesse et études est un entrepreneur et inventeur américain, souvent qualifié de visionnaire[1], et une figure majeure de l'électronique grand public, notamment pionnier de l'avènement de l'ordinateur personnel, du baladeur nu- mérique, du smartphone et de la tablette tactile. Co- fondateur, directeur général et président du conseil d'administration d'Apple Inc, il dirige aussi les studios Pixar et devient membre du conseil d'administration de Disney lors du rachat en 2006 de Pixar par Disney. Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak et Ronald Wayne créent Apple le 1er avril 1976 à Cupertino. Au début des années 1980, Steve Jobs saisit le potentiel commercial des travaux du Xerox Parc sur le couple interface graphique/souris, ce qui conduit à la conception du Lisa, puis du Macintosh en 1984, les premiers ordinateurs grand public à profi- 1966 Crist Drive, Los Altos. L'ancienne maison des Jobs. -

Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers

Profiles of People of Interest to Young Volume 21—2012 Readers Annual Cumulation Cherie D. Abbey Managing Editor 155 West Congress Suite 200 Detroit, MI 48226 Contents Preface. 7 Adele 1988-. 11 British Singer and Songwriter; Grammy-Award Winning Creator of the Hit Albums 19 and 21 Rob Bell 1970-. 23 American Religious Leader, Author, Speaker, and Founding Pastor of the Mars Hill Bible Church Big Time Rush . 39 Logan Henderson, James Maslow, Carlos Pena Jr., and Kendall Schmidt American Pop Music Group, TV Actors, and Stars of the Nickelodeon Series “Big Time Rush” Judy Blume 1938- . 51 American Author of Juvenile, Young Adult, and Adult Fiction, Including the Award-Winning and Best-Selling Books Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret; Deenie; Blubber; Forever; Tiger Eyes; the Fudge Series; and Many More Cheryl Burke 1984- . 75 American Dancer, Choreographer, and First Professional Dancer to Win Back-to-Back “Dancing with the Stars” Championships Chris Daughtry 1979- . 87 American Rock Musician, Lead Singer of the Group Daughtry, and Finalist on “American Idol” Ellen DeGeneres 1958-. 101 American Actor, Comedian, and Award-Winning Host of the Hit TV Talk Show “The Ellen DeGeneres Show” 3 Drake 1986-. 115 Canadian-American Rapper and Actor on “Degrassi: The Next Generation” Kevin Durant 1988- . 127 American Professional Basketball Player, Forward for the Oklahoma City Thunder Dale Earnhardt Jr. 1974-. 147 American Professional Race Car Driver and Nine-Time Winner of NASCAR’s Most Popular Driver Award Zaha Hadid 1950- . 167 Iraqi-Born British Architect, Designer, and First Female Winner of the Pritzker Prize, Architecture’s Highest Honor Josh Hamilton 1981- . -

Steve Jobs (Q19837)

Steve Jobs (Q19837) From Wikidata Retrieved from "https://www.wikidata.org/w/index.php?title=Q19837&oldid=235920743" This page was last modified on 21 July 2015, at 12:58. American entrepreneur and founder of Apple Inc. Steven Paul Jobs | Steven Jobs In more languages Statements employer Apple Inc. 0 references child Lisa Brennan-Jobs 0 references sex or gender male 2 references country of citizenship United States of America 0 references place of birth San Francisco 1 reference place of death Palo Alto 1 reference image Steve Jobs Headshot 2010-CROP.jpg 0 references Commons category Steve Jobs 1 reference VIAF identifier 84237107 5 references LCAuth identifier n87883336 3 references BnF identifier 12154091r 1 reference SUDOC authorities 03004460X 1 reference sister Mona Simpson 1 reference ISNI 0000 0000 7861 3326 1 reference religion Buddhism 0 references GND identifier 118868284 1 reference IMDb identifier nm0423418 2 references NDL identifier 00620888 1 reference signature Steve Jobs signature.svg 1 reference cause of death pancreatic cancer 0 references NKC identifier js20050718011 0 references date of birth 24 February 1955 2 references date of death 5 October 2011 3 references human 1 reference Category:Steve Jobs 0 references NLI (Israel) identifier 000397959 0 references NTA identifier (Netherlands) 071962301 0 references NLA identifier 49863558 0 references 48380231 0 references BNE identifier XX5098457 0 references Commons gallery Steve Jobs 1 reference Freebase identifier /m/06y3r 1 reference SBN identifier IT\ICCU\TO0V\653584 0 references -

Oct09 25 Years!

CELEBRATING 25 YEARS! OCT09 by V i V i a n D aV i s CSW Mona Simpson Q&A wiTh The besTselling nOVELIST And PROFESSOR of english Mona Simpson writes novels. Her 1987 sequel: The Lost Father, published in 1992. child. That same year Granta named Simpson debut, Anywhere But Here, follows Adele In it, Simpson’s character searches for her one of America’s Best Young Novelists. In and Ann August, a mother and daughter Egyptian father, who’s been absent all her 2000, Simpson published Off Keck Road, a who move from the Midwest to Los Angeles life, and her quest takes her to New York novel about a small town spinster, a man who in search of a less ordinary life. The novel City and eventually, Egypt. Four years later, has always been in her life, and a young girl, went on to be a national bestseller, winning Simpson returned with A Regular Guy (1996), who completes the odd triangle. This work the Whiting Award in 1986, catapulting the another work that limns the father-daughter was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award. author into the literary spotlight. Simpson connection, this time between a Silicon Valley A fascination with places and the people followed her first novel’s success with a millionaire and his estranged, illegitimate who inhabit them characterizes Simpson’s 1 toc OCT09 2 OCT09 25th Anniversary Year: Upcoming Highlights This year marks OUr 25Th anniVersary!! sideration for a number grants, includ- I hope you will all join us for CSW’s birthday CSW has countless achievements to its credit ing a Haynes foundation grant.