Marquess of Rockingham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAHS-009/Fall 2004

Midwest Art History Society NEWSLETTERNumber 31, 2004 MAHS Conference 2005, Cincinnati, Ohio, April 7-9, 2005 Zaha Hadid’s Rosenthal Contemporary Arts Center. In addition, there will be a tour of University of Cincinnati campus architecture Saturday morning featuring the Vontz Center for Molecular Studies, Frank Gehry, the Engineering Research Center, Michael Graves, and the College-Conservatory of Music by Henry Cobb. Walking tours of down Cincinnati’s public art will be offered both Friday and Saturday mornings. A field trip to Shakertown will be available Sunday, with an optional drop-off at the airport at the end of the day. Session will include several linked to local culture and events, such as Ohio Valley Architecture. A Whistler session will complement an exhibition at Aronoff Center for Design and Art, Peter Eisenman, 1996, University of Cincinnati, the Taft Museum of Art. Other interesting ses- Cincinnati, Ohio. sions include “African Art Today: Definitions and Directions,” “Baroque Around the World,” “The Role of Art History in Art Museums Today,” and Queen City Offers Exciting Architecture, New Special tours will be offered on Wednesday and “Design/History/Feminism/Visual Cultural Institutions, and Full Range of Sessions Saturday afternoons. Conference attendees will Studies.” A complete list of sessions, along with have the opportunity to take an orientation tour instructions for submitting proposals, can be MAHS invites abstracts for its 32st annual confer- (by bus) of Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky on found on pages 2-4 of the newsletter. Hotel ence, to be held April 7-9, 2005 in Cincinnati, Wednesday afternoon. A walking tour of down- information and a conference registration form Ohio. -

Loans in And

LOANS TO THE NATIONAL GALLERY April 2018 – March 2019 The following pictures were on loan to the National British (?) The Fourvière Hill at Lyon (currently Leighton Archway on the Palatine Gallery between April 2018 and March 2019 on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Leighton Houses in Venice *Pictures returned Bürkel Distant View of Rome with the Baths Leighton On the Coast, Isle of Wight of Caracalla in the Foreground (currently on loan Leighton An Outcrop in the Campagna THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST / to the Ashmolean Museum Oxford) Leighton View in Capri (currently on loan HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Buttura A Road in the Roman Campagna to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Fra Angelico Blessing Redeemer Camuccini Ariccia Leighton A View in Spain Gentile da Fabriano The Madonna and Camuccini A Fallen Tree Trunk Leighton The Villa Malta, Rome Child with Angels (The Quaratesi Madonna) Camuccini Landscape with Trees and Rocks Possibly by Leighton Houses in Capri Gossaert Adam and Eve (currently on loan to the Ashmolean Mason The Villa Borghese (currently on loan Leighton Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna is carried Museum, Oxford) to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) in Procession through the Streets of Florence Cels Sky Study with Birds Michallon A Torrent in a Rocky Gorge (currently Pesellino Saints Mamas and James Closson Antique Ruins (the Baths of Caracalla?) on loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Closson The Cascade at Tivoli (currently on loan Michallon A Tree THE WARDEN AND FELLOWS OF to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Nittis Winter Landscape ALL -

Banksy. Urban Art in a Material World

Ulrich Blanché BANKSY Ulrich Blanché Banksy Urban Art in a Material World Translated from German by Rebekah Jonas and Ulrich Blanché Tectum Ulrich Blanché Banksy. Urban Art in a Material World Translated by Rebekah Jonas and Ulrich Blanché Proofread by Rebekah Jonas Tectum Verlag Marburg, 2016 ISBN 978-3-8288-6357-6 (Dieser Titel ist zugleich als gedrucktes Buch unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-3541-2 im Tectum Verlag erschienen.) Umschlagabbildung: Food Art made in 2008 by Prudence Emma Staite. Reprinted by kind permission of Nestlé and Prudence Emma Staite. Besuchen Sie uns im Internet www.tectum-verlag.de www.facebook.com/tectum.verlag Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Table of Content 1) Introduction 11 a) How Does Banksy Depict Consumerism? 11 b) How is the Term Consumer Culture Used in this Study? 15 c) Sources 17 2) Terms and Definitions 19 a) Consumerism and Consumption 19 i) The Term Consumption 19 ii) The Concept of Consumerism 20 b) Cultural Critique, Critique of Authority and Environmental Criticism 23 c) Consumer Society 23 i) Narrowing Down »Consumer Society« 24 ii) Emergence of Consumer Societies 25 d) Consumption and Religion 28 e) Consumption in Art History 31 i) Marcel Duchamp 32 ii) Andy Warhol 35 iii) Jeff Koons 39 f) Graffiti, Street Art, and Urban Art 43 i) Graffiti 43 ii) The Term Street Art 44 iii) Definition -

Early 19Th Century (Romanticism) 1. Caspar David Friedrich 2. JMW Turner

SESSION 9 (Monday 7th May) Early 19th Century (Romanticism) 1. Caspar David Friedrich 1.1. The Monk by The Sea 1808-10 Oil on canvas (110 x 171cm) Alte Natinagalerie, Berlin 1.2. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog 1818 (95 x 75cm) Kuntshalle, Hamburg 2. JMW Turner [RM] 2.1. The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons Philadelphia Museum of Art 2.2. The Slave Ship 1840 Oil on canvas (91 x 122cm) Museum of Fine Arts. Boston 2.3. Rain, Steam and Speed 1844 Oil on canvas (91 x 121cm) National Gallery 3. John Constable [RM] 3.1. The Haywain. 1821 Oil on canvas (130 x 185cm) National Gallery 3.2. Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, 1831, Oil on canvas, 151.8 x 189.9 cm (National Gallery) 4. George Stubbs 4.1. Whistlejacket c1762 Oil on canvas (292 x 246cm) National Gallery 5. Sir Edward Landseer [RM] 5.1. The Monarch of the Glen 1850/51 Oil on canvas Scottish national Gallery 6. Eugene Delacroix [RM] 6.1. The Massacre at Chios 1824 Oil on canvas (419 x 354cm) Louvre 6.2. The Death of Sardanapalus. 1827 Oil on canvas (392 x 496 cm) Louvre 6.3. Liberty leading the People 1830 Oil on canvas (102 x 128cm) Louvre 7. John Martin 7.1. The Great Day of His Wrath 1851-3 Oil on canvas (197 x 303cm) Tate Britain Title screen – Turner’s Painter at the Easel In my view, the late 18th and early 19th century saw a step change in the history of paintings. -

History & Myth in South Yorkshire

History & Myth in South Yorkshire 1 History & Myth in South Yorkshire HISTORY AND MYTH IN SOUTH YORKSHIRE Stephen Cooper Copyright Stephen Cooper, 2019 The right of Stephen Cooper to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 History & Myth in South Yorkshire To the staff and volunteers at Wentworth Woodhouse. 3 History & Myth in South Yorkshire I often think it odd that it should be so dull, for a great deal of it must be invention. Quotation in E.H.Carr’s What is History? (1961). 4 History & Myth in South Yorkshire CONTENTS List of illustrations Preface by David Allott Introduction Acknowledgements 1 THE BATTLE OF BRUNANBURH The Problem; Solutions; The Forgetting of Brunanburh 2 CONISBROUGH & IVANHOE Sir Walter Scott; The Norman Yoke; Merrie England 3 THOMAS ROTHERHAM’S COLLEGE The College; William Senes & Heresy; The Destruction of the College 4 WITCHCRAFT IN YORKSHIRE William West; Sorcery; The Witch-craze; The Waning of the Superstition 5 THE DRAGON OF WANTLEY The Legend; Sheffield; Wharncliffe Chase 6 STRAFFORD’S LOYAL SERVANT John Marris; Wentworth & Strafford; The Sieges of Pontefract Castle; Trial & Execution 7 ROCKINGHAM & AMERICA In Government; The Dispute with George III; The First Administration; The American War of Independence; The Second Administration 8 THE CLIFFE HOUSE BURGLARY The Burglary; The Investigation; Trial & Conviction; Myths 5 History & Myth in South Yorkshire 9 MUTTON TOWN The Raid; The Arrest; The Trial; Mutton Town 10 THE -

Sir William Strickland Racing

Sir William Strickland, York House, The Talbot Hotel and Langton Wold Racecourse The association between York House and the Strickland Hunting Lodge and the Langton Wold Racecourse and the racing industry in Malton and Norton is strong and significant. The site of the Talbot Hotel was purchased by Strickland from the Hebblethwaite’s in 1672. York House belonged to Strickland after 1684 and his passion for racing, horse-breeding and his role as Master of Ceremonies at Langton Wold seems to have informed the architectural design of the garden front off York House (see above). York House in its exterior appearance as well as its interior lay-out and design, and that of its gardens was transformed by Strickland as a vehicle of display and ceremony associated not only with his role as MP for the town but in his role and status within the local and regional horse-racing fraternity. It was a place for business meetings and social events. York House may have briefly become the Malton residence of the Watson Wentworths after 1739 when they acquired it from the executors of the 4 th Baronet’s estate. The Marquess of Rockingham was, of course, himself an avid racehorse breeder and owner and ran horses in the area and the role for York House that Strickland created will have continued during Rockingham’s time, for all that at this time he was mainly resident at Wentworth Woodhouse, one of Europe’s largest houses, works to which by John Carr would be continued by his son Charles after 1760 and would include the construction after 1766 of grand stables for some 84 horses, of which Whistlejacket had already become the most famous, winning the 2,000 Guineas at York in 1759 and being painted by George Stubbs in 1762. -

Copyright by Kevin Jordan Bourque 2012

Copyright by Kevin Jordan Bourque 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Kevin Jordan Bourque certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Blind Items: Anonymity, Notoriety, and the Making of Eighteenth-Century Celebrity Committee: Janine Barchas, Co-Supervisor Lisa L. Moore, Co-Supervisor Lance Bertelsen David Brewer Elizabeth A. Hedrick Blind Items: Anonymity, Notoriety, and the Making of Eighteenth-Century Celebrity by Kevin Jordan Bourque, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2012 “Talent is not what Uncle Buck and I deal in, Miss Van Allen,” I said, lightly resting my hand on Buck’s clenched fist. “We deal in myths. At any given moment the world requires one full-bodied blonde Aphrodite (Jean Harlow), one dark siren of flawless beauty (Hedy Lamarr), one powerful inarticulate brute of a man (John Wayne), one smooth debonair charmer (Melvyn Douglas), one world-weary corrupt lover past his prime (Humphrey Bogart), one eternal good-sex woman-wife (Myrna Loy), one wide-eyed chicken boy (Lon McCallister), one gentle girl singer (Susanna Foster), one winning stud (Clark Gable), one losing stud outside the law (James Cagney), and so on. Olympus supports many gods and goddesses and they are truly eternal, since whenever one fades or falls another promptly takes his place, for the race requires that the pantheon be always filled... And so, like priestesses, despite all personal hardship, we must constantly test and analyze the young men and women of America in order to find the glittering few who are immortal, who are the old, the permanent gods of our race reborn.” – Gore Vidal, Myra Breckinridge (1968) Acknowledgments My time working on and thinking about this project has been spent within a coterie of exceptionally generous, brilliant and nurturing people. -

An Adoring Friend from Across the Ocean Discusses Jeanne Mellin Herrick’S Unique Artwork, Unflinching Horsemanship, and Her Place in Our Breed’S History

u FOCUS ON WOMEN IN OUR INDUSTRY u An adoring friend from across the ocean discusses Jeanne Mellin Herrick’s unique artwork, unflinching horsemanship, and her place in our breed’s history. By Doug Wade ometimes in life paths cross, fate intervenes and you meet cousins,” Jeanne developed and honed her skills with the paint brush, individuals who shape your life. Such is the case here. oils, gouache, watercolor, and also started to learn about sculpting, A boy from the United Kingdom meets an effervescent; calligraphy, and design. Whenever in conversation about RISD, there charismatic artist and horsewoman from the United States would always be a raised eyebrow as she explained (animatedly) Sand a life lasting friendship is born. I first met Jeanne Mellin Herrick how the tutors never let her paint her beloved horses, but “they’d when I was about 10 years of age. She had flown into Great Britain to rather me go to life drawing classes to paint and draw people!” This judge the first Morgan horse show, the Hertfordshire County Show, infuriated Jeanne. She dreamed, and day dreamed, about her four- and she was staying at our family home. That very first evening, as a legged friends. All Jeanne wanted to do was paint and draw horses. horse crazy kid, I was mesmerized—Jeanne talked and shared many This is what really mattered to the young aspiring artist. beautiful images of her horses and, of course, of her paintings. I was I went to work for Fred and Jeanne Herrick during long, completely hooked and transfixed by this amazing lady! glorious, and very happy summers of the 1980s at Saddleback The story of Jeanne Mellin Herrick has been well documented. -

Beyond the Pale and Back Again: Contemporary British Art and the Case of Mark Wallinger

BEYOND THE PALE AND BACK AGAIN: CONTEMPORARY BRITISH ART AND THE CASE OF MARK WALLINGER By BRANTLEY BALDWIN JOHNSON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Brantley Baldwin Johnson 2 To the most important professors who helped me see this project through: Tom Johnson and Mary Baldwin 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank first and foremost my faculty committee members: Dr. Alexander Alberro, Dr. Florence Babb, Dr. Elizabeth Ross, Dr. Eric Segal, and Dr. Shepherd Steiner. My Floridian friends, students, and mentors have enhanced my confidence and reassured my unease during many stressful occasions. Several colleagues in London were critical in the research and planning stages: most notably Anthony Spira at the Whitechapel Gallery and Milton Keynes Gallery. The staff at the Anthony Reynolds Gallery (Maria Stathi in particular) allowed me unlimited access to rare video works and press materials. This dissertation was enriched as well by the generosity and candidness of Mark Wallinger himself. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................7 ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................................10 -

HLF Major Grants – the First 100

Case studies HLF Major Grants – The first 100 June 2015 1 Contents HLF Major Grants – The first 100 .......................................................................................... 1 Ashmolean Museum ............................................................................................................. 5 Beaney House of Art & Knowledge ....................................................................................... 7 Big Pit ................................................................................................................................... 8 Birmingham Town Hall ........................................................................................................ 11 Bletchley Park ..................................................................................................................... 12 Brighton Museum and Art Gallery ....................................................................................... 15 British Film Institute Film and TV Archive ............................................................................ 17 British Museum: Education and Information Centre ............................................................ 18 Cardiff Castle ...................................................................................................................... 20 Christ Church, Spitalfields ................................................................................................... 22 Churchill Archive ................................................................................................................ -

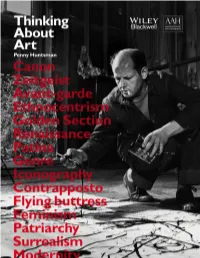

Thinking About Art : a Thematic Guide to Art History / Penny Huntsman

Thinking About Art Thinking About Art A Thematic Guide to Art History Penny Huntsman Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913, bronze, 1175 × 876 × 368 mm, cast 1972. London, Tate. Source: © Tate, London 2015. This edition first published 2016 © 2016 Association of Art Historians Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Penny Huntsman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and prod- uct names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

GEORGE STUBBS Stubbs Portrait of a Gentleman Upon a Grey Hunter, 1781 International Art Dealers & Advisors

TRINITY HOUSE international art dealers & advisors GeorgeGEORGE STUBBS Stubbs Portrait of a gentleman upon a grey hunter, 1781 International Art Dealers & Advisors Trinity House Paintings Trinity House Paintings is an international art dealership. We specialise in Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, Modern British and 19th Century works, along with other exceptional pieces. We have a strong reputation for the quality of the artworks that we exhibit and offer to our clients, be they paintings, drawings or sculptures. Established in 2006 by Steven Beale, Trinity House has become a major player in the UK and global art world. Originating in the picturesque Cotswolds village of Broadway, we expanded into Mayfair, London in 2009, and in 2011 we opened our third gallery in Manhattan, New York, with our fourth gallery in San Francisco opening this year. Having these four locations, in addition to exhibiting at the major international art fairs in Europe and the US has allowed us to have personal relationships with our clients across the globe. At Trinity House, we act on behalf of private collectors, interior designers and museums, as well as other interested customers, advising on every aspect of sourcing, buying, selling and maintaining fine art. We recognize that clients need not only to be offered fine paintings and works of art, but also to be provided with expert, straightforward advice on buying art and building a collection. Our aim is to make the market approachable by acting as guides through the various aspects involved in buying and selling art. We have a strong reputation for the quality of the art that we exhibit and offer to our clients.