History & Myth in South Yorkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Laughton-En-Le-Morthen Parish

LAUGHTON-EN-LE-MORTHEN PARISH COUNCIL Venue: Virtual Meeting Date: Wednesday, 18th November, 2020 Time: 7.15 p.m. A G E N D A 1. Agenda (Pages 1 - 4) Page 1 Agenda Item 1 Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish Council The Village Hall Firbeck Avenue Laughton-en-le-Morthen S25 1YD Clerk: Mrs C J Havenhand Telephone - 01709 528823 Email: [email protected] Notice of an ordinary meeting of Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish Council to be held on WEDNESDAY 18th NOVEMBER 2020 at 7.15pm. The meeting will be held remotely via a remote meeting platform. Access - The remote meeting platform can be accessed by using the following link: Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89433462440?pwd=RWFoTUtZcTJ2cllJeWhXdk5PaVF6dz09 Meeting ID: 894 3346 2440 Password: 661423 By Landline - By ringing any of these UK numbers and keying in your meeting ID and Password when asked: • 0203 481 5240 • 0131 460 1196 • 0203 051 2874 • 0203 481 5237 Please note you that depending on your call plan you may be charged for these numbers. Find your local number: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kdUrPoXGWf Meeting ID: 894 3346 2440 Password: 661423 This meeting is open to the public by virtue of the Public Bodies (Administration to Meetings) Act 1960 s1 and The Local Authorities (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority Meetings) (England) Regulations 2020. Yours Faithfully Mrs Caroline Havenhand Clerk and Financial Officer 12TH November 2020 Apologies for absence should be notified to the Clerk prior to the meeting. Page 1 of 4 Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish Council Agenda Ordinary Meeting 18th November 2020 Page 2 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION Following completion of the first business (election of Chairperson/receipt of declarations of Acceptance of office as necessary) and information on the recording of meetings, the Parish Council will invite members of the public to put questions on relevant parish matters or to make statements appertaining to items on the agenda for the meeting, prior to the commencement of other business. -

Agenda Annex

FORM 2 SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCILAgenda Annex Full Council Report of: Chief Executive ________________________________________________________________ Report to: Council ________________________________________________________________ Date: 4th March 2016 ________________________________________________________________ Subject: Polling District and Polling Place Review ________________________________________________________________ Author of Report: John Tomlinson 27 34091 ________________________________________________________________ Summary: Following the recent ward boundary changes the Authority is required to allocate Polling Districts and Polling Places. ________________________________________________________________ Reasons for Recommendations: The recommendations have been made dependent on the following criteria: 1. All polling districts must fall entirely within all Electoral areas is serves 2. A polling station should not have more than 2,500 electors allocated to it. ________________________________________________________________ Recommendations: The changes to polling district and polling place boundaries for Sheffield as set out in this report are approved. ________________________________________________________________ Background Papers: None Category of Report: OPEN Form 2 – Executive Report Page 1 January 2014 Statutory and Council Policy Checklist Financial Implications YES Cleared by: Pauline Wood Legal Implications YES Cleared by: Gillian Duckworth Equality of Opportunity Implications NO Cleared by: Tackling Health -

978–1–137–49934–9 Copyrighted Material – 978–1–137–49934–9

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137–49934–9 © Steve Ely 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–1–137–49934–9 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

An Heritage Impact Assessment and Historic Buildings Appraisal of the Rising Sun, Bamford, Derbyshire

An Heritage Impact Assessment and Historic Buildings Appraisal of the Rising Sun, Bamford, Derbyshire ARS Ltd Report 2017/151 OASIS archaeol5-304640 December 2017 Compiled By: Emma Grange and Michelle Burpoe Archaeological Research Services Ltd Angel House Portland Square Bakewell Derbyshire DE45 1HB Checked By: Clive Waddington MCIfA Tel: 01629 814540 Fax: 01629 814657 [email protected] www.archaeologicalresearchservices.com A Heritage Impact Assessment and Historic Buildings Appraisal of the Rising Sun, Bamford, Derbyshire A Heritage Impact Assessment and Historic Buildings Appraisal of the Rising Sun, Bamford, Derbyshire Archaeological Research Services Ltd Report 2017/151 December 2017 © Archaeological Research Services Ltd 2017 Angel House, Portland Square, Bakewell, Derbyshire, DE45 1HB www.archaeologicalresearchservices.com Prepared on behalf of: GiGi Developments Ltd Date of compilation: December 2017 Compiled by: Emma Grange and Michelle Burpoe Checked by: Clive Waddington MCIfA Local Planning Authority: Peak District National Park Authority Site central NGR: SK 19489 82837 i A Heritage Impact Assessment and Historic Buildings Appraisal of the Rising Sun, Bamford, Derbyshire EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Archaeological Research Services Ltd was commissioned by GiGi Developments Ltd to carry out a heritage impact assessment and historic buildings appraisal of the former Rising Sun Public House and Hotel, Bamford, Derbyshire. This heritage impact assessment and historic buildings appraisal has been commissioned ahead of the submission of a planning application for the proposed redevelopment of the site for hotel use with associated car parking to the side and rear. The assessment has identified that the majority of the Rising Sun complex is of a later date than the 18th century and is largely of little historical or architectural significance. -

Thorne Inset Campsall and Norton Inset Mexborough Inset Doncaster's

M L B D a S o Elmsa South Elmsall n s e s W ay ll L o T w 496 to Wakefield e T 408 405 For continuation of 301 to Askern 84b to Sykehouse u e n he d n a A Kirk 2 bb L Thorne Road e w a A1 L e n A L 51 B ’s W C a D Kirkton La E 409 407.X45 M 8877 d o A alk C 87a87a Field Lane e services in this area see n E For continuation of a r 6 t g h r Thorne Inset Northgate 3 a e Bramwith a o t h 303 51a n Burghwallis R u o r 8 g a 412 ckley 84 s R h i 301 s r Lan Campsall and Norton inset right r t e h c services in this area 303 a G 84b d 8 r h R 8 Ha L l D t H R 84b ig 303 e o o S 84a a h 8a o ll R a H n n 8787 see Thorne inset right fi c a d t 8a d M 84a e 8 8a 87 87a a St. a 496 d La . a gh s 303 Owston ne 84b z t e e id d 87a87a H 8877 r Thorpe 84 l e d 84 a R l o R n o 301 e R 87a87a d . 87a87a . L a a ne Skellow r d a a in Balne e L M n 301 t L A e s La e Hazel i a Stainforth l 6 t ll . -

Publications List

Doncaster & District Family History Society Publications List August 2020 Parishes & Townships in the Archdeaconry of Doncaster in 1914 Notes The Anglican Diocese of Sheffield was formed in 1914 and is divided into two Archdeaconries. The map shows the Parishes within the Archdeaconry of Doncaster at that time. This publication list shows Parishes and other Collections that Doncaster & District Family History Society has transcribed and published in the form of Portable Document Files (pdf). Downloads Each Parish file etc with a reference number can be downloaded from the Internet using: www.genfair.co.uk (look for the Society under suppliers) at a cost of £6 each. Postal Sales The files can also be supplied by post on a USB memory stick. The cost is £10 each. The price includes the memory stick, one file and postage & packing. (The memory stick can be reused once you have loaded the files onto your own computer). Orders and payment by cheque through: D&DFHS Postal Sales, 18 Newbury Way, Cusworth, Doncaster, DN5 8PY Additional files at £6 each can be included on a single USB memory stick (up to a total of 4 files depending on file sizes). Example: One USB memory stick with “Adlingfleet” Parish file Ref: 1091 = £10. 1st Additional file at £6: the above plus “Adwick le Street” Ref: 1112 = Total £16. 2nd Additional file at £6: “The Poor & the Law” Ref: 1125 = Total £22 Postage included. We can also arrange payment by BACs, but for card and non-sterling purchases use Genfair While our limited stocks last we will also supply files in the form of a CD at £6 each plus postage. -

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Procurement Transparency Payments "March 2021"

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Procurement Transparency Payments "March_2021" Supplier Value Paid (PETTY CASH ACCOUNT) 3,186.73 1974 RAPPORT LTD 1,428.00 1ST CALL MOBILITY LTD 4,280.40 3M UNITEK UK (ORTHODONTIC PRODUCTS) 459.26 4 WAYS HEALTHCARE LIMITED 13,373.50 A AGARWAL 1,122.60 A CASTANON 120.00 A CROPPER 240.00 A DARLING 10.20 A DOUGLAS 1,542.00 A FORRESTER 2,036.80 A GRAFTON 890.10 A GROSSMAN 616.00 A L CLINICIAN LIMITED (RAJAK) 5,552.50 A M KENNEDY 90.20 A MARSHALL 36.96 A MARSHALL 298.40 A MAZAI 2,731.80 A PARKIN 30.80 A RIDSDALE 6,246.58 A SHERRIDAN 20,000.00 A W BENT LTD 1,133.10 A WILKINSON 250.00 A ZUPPINGER 16.00 AAH PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 895,374.69 AB SCIENTIFIC LTD 813.12 ABBOTT LABORATORIES LTD 1,600.45 ABBOTT MEDICAL UK LTD 69,289.20 ABBOTT RAPID DIAGNOSTICS LTD 253.32 ABILITY HANDLING LTD 193.20 ABILITY SMART LIMITED 493.00 AC COSSOR & SON (SURGICAL) LTD 871.32 AC MAINTENANCE LTD 2,415.60 ACCORD FLOORING LTD 4,410.60 ACE JANITORIAL SUPPLIES LIMITED 22,570.21 ACES 189.00 ACORN INDUSTRIAL SERVICES LTD 612.75 ACTIVE DESIGN LTD 247.20 ACUMED LTD 6,013.14 ADAM ROUILLY LTD 2,744.40 ADEC DENTAL UK LTD 1,773.20 ADG ENGINEERING LTD 1,663.20 ADI ENVIRONMENTAL LTD 2,343.00 ADMOR LTD 387.88 ADUR & WORTHING COUNCILS 121.89 Page 1 of 35 Supplier Value Paid ADVANCED ACCELERATOR APPLICATIONS 183,439.50 ADVANCED DIGITAL INNOVATION (UK) LTD 1,680.26 ADVANCED HEALTH & CARE 32,436.58 ADVANCED LABELLING LIMITED 1,601.24 ADVANCED MEDICAL SYSTEMS LTD 163.20 ADVANCED STERILIZATION PRODUCTS (UK) LTD 335.40 ADVISEINC LTD 13,920.00 -

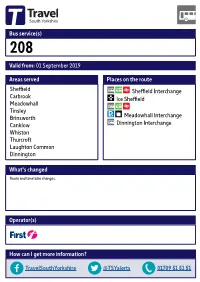

Valid From: 01 September 2019 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas

Bus service(s) 208 Valid from: 01 September 2019 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Carbrook Ice Sheffield Meadowhall Tinsley Brinsworth Meadowhall Interchange Canklow Dinnington Interchange Whiston Thurcroft Laughton Common Dinnington What’s changed Route and timetable changes. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 208 01/02/2019 Scholes Parkgate Dalton Thrybergh Braithwell Ecclesfield Ravenfield Common Kimberworth East Dene Blackburn ! Holmes Meadowhall, Interchange Flanderwell Brinsworth, Hellaby Bonet Lane/ Bramley Wincobank Brinsworth Lane Maltby ! Longley ! Brinsworth, Meadowhall, Whiston, Worrygoose Lane/Reresby Drive ! Ñ Whitehill Lane/ Meadowhall Drive/ Hooton Levitt Bawtry Road Meadowhall Way 208 Norwood ! Thurcroft, Morthen Road/Green Lane Meadowhall, Whiston, ! Meadowhall Way/ Worrygoose Lane/ Atterclie, Vulcan Road Greystones Road Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Green Arbour Road ! Pitsmoor Atterclie Road/ Brinsworth, Staniforth Road Comprehensive School Bus Park ! Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Peter Street Laughton Common, ! ! Station Road/Hangsman Lane ! Atterclie, AtterclieDarnall Road/Shortridge Street ! ! ! Treeton Dinnington, ! ! ! Ulley ! Doe Quarry Lane/ ! ! ! Dinnington Comp School ! Sheeld, Interchange Laughton Common, Station Road/ ! 208! Rotherham Road 208 ! Aughton ! Handsworth ! 208 !! Manor !! Dinnington, Interchange Richmond ! ! ! Aston database right 2019 Swallownest and Heeley Todwick ! Woodhouse yright p o c Intake North Anston own r C Hurlfield ! data © y Frecheville e Beighton v Sur e South Anston c ! Wales dnan ! r O ! ! ! ! Kiveton Park ! ! ! ! ! ! Sothall ontains C 2019 ! = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop 24 hour clock 24 hour clock Throughout South Yorkshire our timetables use the 24 hour clock to avoid confusion between am and pm times. -

Manor Oaks Farm, Manor Lane, Sheffield, South Yorkshire Volume 1: Text and Illustrations

Archaeological Research & Consultancy at the University of Sheffield Graduate School of Archaeology West Court 2 Mappin Street Sheffield S1 4DT Phone 0114 2225106 Fax 0114 2797158 Project Report 873b.3(1) Archaeological Building Recording and Watching Brief: Manor Oaks Farm, Manor Lane, Sheffield, South Yorkshire Volume 1: Text and Illustrations July 2007 By Mark Douglas and Oliver Jessop Prepared For: GREEN ESTATES LTD. Manor Lodge 115 Manor Lane Sheffield S2 1UH Manor Oaks Farm, Manor Lane, Sheffield, South Yorkshire National Grid Reference: SK 3763 8685 Archaeological Building Recording and Watching Brief Report 873b.3(1) © ARCUS 2007 Fieldwork Survey Reporting Steve Baker, Lucy Dawson, Mark Douglas, Steve Mark Douglas, Oliver Jessop and Mark Stenton Duckworth, Tegwen Roberts, Alex Rose-Deacon, Oliver Jessop and Simon Jessop Illustrations Archive Kathy Speight Lucy Dawson Checked by: Passed for submission to client: Date: Date: Oliver Jessop MIFA Anna Badcock Project Manager Assistant Director Archaeological Building Recording and Watching Brief: Manor Oaks, Sheffield – i ARCUS Report 873b.3(1) - July 2007 CONTENTS NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY................................................................................................ VI 1 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................7 2 AIMS AND METHODOLOGY............................................................................................7 2.1 Aims ................................................................................................................................. -

Convocations Called by Edward IV and Richard of Gloucester in 1483: Did They Ever Take Place?

Convocations Called by Edward IV and Richard of Gloucester in 1483: Did They Ever Take Place? ANNETTE CARSON IN I 4 8 3 , THE YEAR OF THREE KINGS, a series of dramatic regime changes led to unforeseen disruptions in the normal machinery of English government. It was a year of many plans unfulfilled, beginning with those of Edward IV who was still concerned over unfinished hostilities with James III of Scotland, and had also made clear his intention to wreak revenge on the treacherous Louis XI of France. All this came to naught when Edward's life ended suddenly and unexpectedly on 9 April. His twelve-year-old son, Edward V, was scheduled to be crowned as his successor, with Edward IV's last living brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, appointed as lord protector. But within two months Richard had become king in his place, with young Edward deposed on the grounds that his father's marriage to Queen Elizabeth Woodville was both bigamous and secret, thus rendering their children illegitimate. Since this article will be looking closely at the events of this brief period, perhaps it will be useful to start with a very simplified chronology of early 1483. The ques- tions addressed concern two convocations, called by royal mandate in February and May respectively, about which some erroneous assumptions will be revealed.' January/February Edward IV's parliament. 3 February A convocation of the southern clergy is called by writ of Edward IV. 9 April Edward IV dies. 17-19 April Edward's funeral takes place, attended by leading clergy. -

Valid From: 01 September 2019 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas Served Chapeltown Tankersley Stocksbridge Places on the Rout

Bus service(s) 201 Valid from: 01 September 2019 Areas served Places on the route Chapeltown Chapeltown Station Tankersley Wentworth Business Park Stocksbridge Fox Valley Retail Park What’s changed Change of operator (Powells) following award of tender. Operator(s) Some journeys operated with financial support from South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 201 18/10/2018 Oxspring Crane Moor Birdwell Thurgoland Pilley Green Moor Tankersley, Wentworth Way/Maple Rd Stocksbridge, Unsliven Road/ Stocksbridge, Ó Smithy Moor Lane Manchester Rd/ Tankersley, Maple Rd/ Opp Stocksbridge Library Wentworth Business Park Ò Stocksbridge, Fox Valley Way/Hunshelf Road 201 Stocksbridge, Manchester Rd/Victoria St Stocksbridge, Fox Valley Way/Manchester Rd High Green Howbrook Deepcar Chapeltown, Cart Rd/Newton Chambers Rd Chapeltown, Cart Rd/Chambers Dr Charltonbrook 201 Chapeltown, Lound Side/Chapeltown Stn database right 2018 and yright p o c own r C data © y e Wharnclie Side Grenoside v Sur e Oughtibridge c dnan r O High Bradfield ontains C 2018 = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop Stopping points for service 201 Chapeltown, Lound Side Station Road Cart Road Thorncliff e Road Tankersley Wentworth Way Maple Road Fox Valley Way Manchester Road Stocksbridge, Unsliven Road Stocksbridge, Unsliven Road Manchester Road Fox Valley Way Tankersley Wentworth Way Maple