Thinking About Art : a Thematic Guide to Art History / Penny Huntsman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Meeting in Columbus, Ohio October 25th-28th, 2017 Conference Chair, Aaron Petten, Columbus College of Art & Design Emma Abercrombie, SCAD Savannah The Millennial and the Millennial Female: Amalia Ulman and ORLAN This paper focuses on Amalia Ulman’s digital performance Excellences and Perfections and places it within the theoretical framework of ORLAN’s surgical performance series The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan. Ulman’s performance occurred over a twenty-one week period on the artist’s Instagram page. She posted a total of 184 photographs over twenty-one weeks. When viewed in their entirety and in relation to one another, the photographs reveal a narrative that can be separated into three distinct episodes in which Ulman performs three different female Instagram archetypes through the use of selfies and common Instagram image tropes. This paper pushes beyond the casual connection that has been suggested, but not explored, by art historians between the two artists and takes the comparison to task. Issues of postmodern identity are explored as they relate to the Internet culture of the 1990s when ORLAN began her surgery series and within the digital landscape of the Web 2.0 age that Ulman works in, where Instagram is the site of her performance and the selfie is a medium of choice. Abercrombie situates Ulman’s “image-body” performance within the critical framework of feminist performance practice, using the postmodern performance of ORLAN as a point of departure. J. Bradley Adams, Berry College Controlled Nature Focused on gardens, Adams’s work takes a range of forms and operates on different scales. -

E N G L I S H

Matura Examination 2017 E N G L I S H Advance Information The written Matura examination in English consists of four main sections (total 90 credits in sections I-III): Section I: Listening (credits: 14) Multiple choice and questions Section II: Reading Comprehension (credits: 20) 1. Short answer questions Section III: Use of English (credits: 56) 1. Synonyms 2. Antonyms 3. Word Formation 4. Sentence Transformation 5. Open Cloze Section IV: Writing, approx. 400 words (the mark achieved in this part will make up 50% of the overall mark) Time management: the total time is 240 minutes. We recommend you spend 120 minutes on sections I-III, and 120 minutes on section IV. Write legibly and unambiguously. Spelling is important in all parts of the examination. Use of dictionary: You will be allowed to use a monolingual dictionary after handing in sections I-III. The examination is based on Morgan Meis’s article “Frank Lloyd Wright Tried to Solve the City”, published in the “Critics” section of the May 22, 2014 issue of The New Yorker magazine. Frank Lloyd Wright Tried to Solve the City by MORGAN MEIS In: The New Yorker, May 22, 2014 Frank Lloyd Wright1 hated cities. He thought that they were cramped and crowded, stupidly designed, or, more often, built without any sense of design at all. He once wrote, “To look at the 5 plan of a great City is 5 to look at something like the cross-section of a fibrous tumor.” Wright was always looking for a way to cure the cancer of the city. -

Artistic Evolution at the Confluence of Cultures

Dochaku: Artistic Evolution at the Confluence of Cultures Toshiko Oiyama A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art, College of Fine Arts University of New South Wales 2011 Acknowledgements Had I known the extent of work required for a PhD research, I would have had a second, and probably a third, thought before starting. My appreciation goes to everyone who made it possible for me to complete the project, which amounts to almost all with whom I came in contact while undertaking the project. Specifically, I would like to thank my supervisors Dr David McNeill, Nicole Ellis, Dr Paula Dawson, Mike Esson and Dr Diane Losche, for their inspiration, challenge, and encouragement. Andrew Christofides was kind to provide me with astute critiques of my practical work, while Dr Vaughan Rees and my fellow PhD students were ever ready with moral support. Special thanks goes to Dr Janet Chan for giving me the first glimpse of the world of academic research, and for her insightful comments on my draft. Ms Hitomi Uchikura and Ms Kazuko Hj were the kind and knowledgeable guides to the contemporary art world in Japan, where I was a stranger. Margaret Blackmore and Mitsuhiro Obora came to my rescue with their friendship and technical expertise in producing this thesis. My sister Setsuko Sprague and my mother Nobuko Oiyama had faith in my ability to complete the task, which kept me afloat. Lastly, a huge thanks goes to my husband Derry Habir. I hold him partly responsible for the very existence of this project – he knew before I ever did that I wanted to do a PhD, and knew when and how to give me a supporting hand in navigating its long process. -

MF-Romanticism .Pdf

Europe and America, 1800 to 1870 1 Napoleonic Europe 1800-1815 2 3 Goals • Discuss Romanticism as an artistic style. Name some of its frequently occurring subject matter as well as its stylistic qualities. • Compare and contrast Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine reasons for the broad range of subject matter, from portraits and landscape to mythology and history. • Discuss initial reaction by artists and the public to the new art medium known as photography 4 30.1 From Neoclassicism to Romanticism • Understand the philosophical and stylistic differences between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine the growing interest in the exotic, the erotic, the landscape, and fictional narrative as subject matter. • Understand the mixture of classical form and Romantic themes, and the debates about the nature of art in the 19th century. • Identify artists and architects of the period and their works. 5 Neoclassicism in Napoleonic France • Understand reasons why Neoclassicism remained the preferred style during the Napoleonic period • Recall Neoclassical artists of the Napoleonic period and how they served the Empire 6 Figure 30-2 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Coronation of Napoleon, 1805–1808. Oil on canvas, 20’ 4 1/2” x 32’ 1 3/4”. Louvre, Paris. 7 Figure 29-23 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Oath of the Horatii, 1784. Oil on canvas, approx. 10’ 10” x 13’ 11”. Louvre, Paris. 8 Figure 30-3 PIERRE VIGNON, La Madeleine, Paris, France, 1807–1842. 9 Figure 30-4 ANTONIO CANOVA, Pauline Borghese as Venus, 1808. Marble, 6’ 7” long. Galleria Borghese, Rome. 10 Foreshadowing Romanticism • Notice how David’s students retained Neoclassical features in their paintings • Realize that some of David’s students began to include subject matter and stylistic features that foreshadowed Romanticism 11 Figure 30-5 ANTOINE-JEAN GROS, Napoleon at the Pesthouse at Jaffa, 1804. -

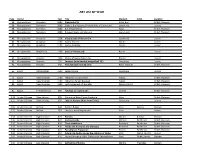

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

Magazine Media

SEPTEMBER 2012: IMAGES & ICONS M M MediaMagazine edia agazine Menglish and media centre issue 41 | septemberM 2012 FEMINIST ICONS OF NORDIC NOIR THE ICONOGRAPHY OF THE ALBUM COVER STEVE JOBS AND THE ICONIC APPLE THE ICONOGRAPHY OF THE WESTERN english english and media centre SELF-IMAGE AND THE | issue | 41 issue | september 2012 MEDIA ICONS IN THE HOOD MM MM MediaMagazine is published by the English and Media Centre, a Welcome to new readers just starting out on your media and non-profit making organisation. film journey – and welcome back to those of you returning to A2 The Centre publishes a wide range and other Level 3 courses. of classroom materials and runs courses for teachers. If you’re This first issue of the year is on Images and Icons – traditionally studying English at A Level, look out the first port of call in Media Studies. You’ll already be well for emagazine, also published by practised in reading and analysing still and moving images, but the Centre. what’s this slippery term icon? And what does iconography mean in the context of The English and Media Centre Media Studies? You’ll know the word from the graphic symbols on your desktop, but 18 Compton Terrace that’s only one meaning. At its simplest, it’s described as: ‘An image; a representation’ London N1 2UN or ‘a symbol resembling the thing it represents’. Most definitions remark on the Telephone: 020 7359 8080 term’s derivation from religious imagery: ‘the representation or picture of a sacred Fax: 020 7354 0133 or sanctified Christian personage, traditionally used and venerated in the Eastern Email for subscription enquiries: Church’ (http://www.thefreedictionary.com/icon). -

Reasons for the Spread of the Glamour Style in Modern Interiors, and The

1/2019 PUA DOI: 10.4467/00000000PUA.19.003.10006 Maryna Gurenko ([email protected]) Kyiv National University of Culture and Arts Reasons for the spread of the glamour style in modern interiors, and the specifics of its manifestation Powody rozpowszechniania stylu glamour w nowoczesnych wnętrzach i specyfika jego manifestacji Abstract The article analyses the origin of a peculiar phenomenon of glamour in different fields of human life and in various types of art. Based on the analysis of the source base, a direct connection of the appearance of glamour with the emergence of a new elite in the political arena was proven. The article has analysed the manifestations of glamour in interior design; it presents an assessment of this phenomenon and examples of the modern interior in the style of glamour. Keywords: glamour, interior design, philosophical and culturological phenomenon Streszczenie W artykule zostały przeanalizowane źródła szczególnego zjawiska splendoru (glamour) w różnych dziedzinach życia człowieka i w różnych odmianach sztuki. Na podstawie przeanalizowania bazy źród- łowej udowodniono bezpośrednie powiązanie powstania splendoru ze stanowieniem na politycznej arenie nowej elity. Przeanalizowano przejawy splendoru w designie wnętrz oraz przedstawiono oce- nę tego zjawiska. Słowa kluczowe: splendor (glamour), design wnętrz, zjawisko filozoficzne i kulturologiczne 42 PRZESTRZEŃ/URBANISTYKA/ARCHITEKTURA 1. INTRODUCTION In the present day, in the stylistic diversity of modern interiors, a separate ‘glamour’ style has emerged as an identification of refinement and treasures, and a demonstration of the social status of a customer and his or her personal image. The use of modernised elements of the styles of previous epochs which personified magnificence and pomposity became widespread. -

Mina, Okojie, Owusu and Cain to Judge Gordon Burn Prize 2021 Prize Opens for Entries Until Wednesday 7 April

Press release: Embargoed until Friday 5 March 2021 Mina, Okojie, Owusu and Cain to judge Gordon Burn Prize 2021 Prize opens for entries until Wednesday 7 April Denise Mina has been appointed as the new chair of the judges of the Gordon Burn Prize. Along with literary journalist and editor Sian Cain, novelist and short story writer Irenosen Okojie, and writer and poet Derek Owusu, she will judge the Gordon Burn Prize 2021. The prize is run in partnership by the Gordon Burn Trust, New Writing North, Faber & Faber and Durham Book Festival, a Durham County Council festival. It is now open for entry until Wednesday 7 April 2021. The Gordon Burn Prize, founded in 2012, remembers the late author of novels including Fullalove and Born Yesterday: The News as a Novel, and non-fiction including Happy Like Murderers: The Story of Fred and Rosemary West and Best and Edwards: Football, Fame and Oblivion. The prize seeks to celebrate the writing of those whose work follows in Burn’s footsteps. It recognises literature that is forward-thinking and fearless in its ambition and execution, often playing with style, pushing boundaries, crossing genres or challenging readers’ expectations. Like Gordon’s own work, the Gordon Burn Prize is open to a diverse range of themes and perspectives drawn from the breadth of today’s cultural and social concerns. It welcomes books by writers emerging from backgrounds underrepresented in the mainstream literary culture. The judges seek work that shows an affinity with the spirit and sensibility of Gordon's literary methods: novels which dare to enter history and interrogate the past; writers of non-fiction brave enough to recast characters and historical events to create a new and vivid reality. -

A Study of Bavarian Rocaille

Dissolving Ornament: A Study of Bavarian Rocaille Olaf Recktenwald School of Architecture McGill University, Montreal March 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Olaf Recktenwald 2016 To my parents Table of Contents List of Illustrations vii Abstract viii Résumé ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Concerning Rocaille 1.1 Introduction 9 1.2 National Considerations 11 1.3 Augsburg and Johann Esaias Nilson 17 1.4 Rocaille Theory 24 1.5 Style, Form, and Space 31 1.6 Rocaille and Rococo 45 1.7 Bavaria’s Silence 50 1.8 Eighteenth-Century Critiques 54 1.9 Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Critiques 75 1.10 Conclusion 84 2. Ornament and Architecture 2.1 Introduction 87 2.2 Architectural Ornament and Ancient Rhetoric 89 2.2.1 Introduction 89 2.2.2 Aristotle 97 2.2.3 Rhetorica ad Herennium 100 2.2.4 Cicero 103 2.2.5 Vitruvius 116 2.2.6 Quintilian 123 2.2.7 Tacitus 131 2.2.8 Conclusion 133 2.3 Alberti’s Interpretation of Ornament 134 2.4 Alberti’s Perspectival Frame 144 2.5 Conclusion 156 3. Nature and Architecture 3.1 Introduction 161 3.2 Biblical Cities 162 3.3 Ruins 170 3.4 Grottoes 178 3.5 Symbols 191 3.6 Conclusion 197 4. Theatricality 4.1 Introduction 199 4.2 Departure from Andrea Pozzo 200 4.3 Relation to Ferdinando Galli-Bibiena 215 4.4 Conclusion 228 Conclusion 231 Illustrations 238 Bibliography 255 List of Illustrations 1. -

2020 Spring Adult Rights Guide

Incorporating Gregory & company Highlights London Book Fair 2020 Highlights Welcome to our 2020 International Book Rights Highlights For more information please go to our website to browse our shelves and find out more about what we do and who we represent. Contents Fiction Literary Fiction 4 to 11 Upmarket Fiction 12 to 17 Commercial Fiction 18 to 19 Crime and Thriller 20 to 31 Non-Fiction Politics, Current Affairs, International Relations 32 to 39 History and Philosophy 40 to 43 Nature and Science 44 to 47 Biography and Memoir 48 to 54 Practical, How-To and Self-Care 55 to 57 Upcoming Publications 58 to 59 Recent Highlights 60 Prizes 61 Film and TV News 62 to 64 DHA Co-Agents 65 Primary Agents US Rights: Veronique Baxter; Jemima Forrester; Georgia Glover; Anthony Goff (AG); Andrew Gordon (AMG); Jane Gregory; Lizzy Kremer; Harriet Moore; Caroline Walsh; Laura West; Jessica Woollard Film & TV Rights: Clare Israel; Penelope Killick; Nicky Lund; Georgina Ruffhead Translation Rights Alice Howe: [email protected] Direct: France; Germany Margaux Vialleron: [email protected] Direct: Denmark; Finland; Iceland; Italy, the Netherlands; Norway; Sweden Emma Jamison: [email protected] Direct: Brazil; Portugal; Spain and Latin America Co-agented: Poland Lucy Talbot: [email protected] Direct: Croatia; Estonia; Latvia; Lithuania; Slovenia Co-agented: China; Hungary, Japan; Korea; Russia; Taiwan; Turkey; Ukraine Imogen Bovill: [email protected] Direct: Arabic; Albania; Bulgaria; Greece; Israel; Italy; Macedonia, Vietnam, all other markets. Co-agented: Czech Republic; Indonesia; Romania; Serbia; Slovakia; Thailand Contact t: +44 (0)20 7434 5900 f: +44 (0)20 7437 1072 www.davidhigham.co.uk General translation rights enquiries: Sam Norman: [email protected] THE PALE WITNESS Patricia Duncker A tour de force of historical fiction from the acclaimed novelist Patricia Duncker According to the Gospel of Matthew, the wife of Pontius Pilate interceded on Jesus’ behalf as Pilate was contemplating the prophet’s fate. -

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus This syllabus runs 13 weeks, with 2 sessions per week. The midterm is scheduled for the end of the seventh week. The final exam is slated for last class meeting but might be shifted to an exam period to give the instructor one more class period. Goals: • understanding of the basic terms, facts, and concepts in art history • comprehension of the progress of art as fluid development of a series of styles and trends that overlap and react to each other as well as to historical events • recognition of the basic concepts inherent in each style, and the outstanding exemplars of each Lecture Notes: For each lecture a number of exemplary works of art are listed. In some cases instructors may wish to discuss all of these works; in other cases they may wish to focus on only some of them. Textbooks: It should be possible to teach this course using any one of the five texts listed below as a primary textbook. Cole et al., Art of the Western World Gardner, Art Through the Ages Janson, History of Art, 2 vols. Schneider Adams, Laurie, A History of Western Art Stokstad, Art History, 2 vols. Writing Assignments: A short, descriptive paper on a single work of art or topic would be in order. Syllabus created by the Core Knowledge Foundation 1 https://www.coreknowledge.org/ Use of this Syllabus: This syllabus was created by Bruce Cole, Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts, Indiana University, as part of What Elementary Teachers Need to Know, a teacher education initiative developed by the Core Knowledge Foundation. -

PENDERECKI Utrenja

572031 bk Penderecki 4/2/09 16:15 Page 8 Stanisław Skrowaczewski, and in 1958 Witold Rowicki was again appointed artistic director and principal conductor, a post he held until 1977, when he was succeeded by Kazimierz Kord, serving until the end of the centenary celebrations in 2001. In 2002 Antoni Wit became general and artistic director of the Warsaw PENDERECKI Philharmonic – The National Orchestra and Choir of Poland. The orchestra has toured widely abroad, in addition to its busy schedule at home in symphony concerts, chamber concerts, educational work and other activities. It now has a complement of 110 players. Utrenja Antoni Wit Hossa • Rehlis • Kusiewicz • Nowacki • Bezzubenkov Antoni Wit, one of the most highly regarded Polish conductors, studied conducting with Henryk Czyz and composition with Krzysztof Penderecki Warsaw Boys’ Choir at the Academy of Music in Kraków, subsequently continuing his studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. He also graduated in law at the Jagellonian University in Kraków. Immediately after completing his studies he was Warsaw Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra engaged as an assistant at the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra by Witold Rowicki and was later appointed conductor of the Poznan Philharmonic, Antoni Wit collaborated with the Warsaw Grand Theatre, and from 1974 to 1977 was artistic director of the Pomeranian Philharmonic, before his appointment as director of the Polish Radio and Television Orchestra and Chorus in Kraków, from 1977 to 1983. From 1983 to 2000 he was the director of the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Katowice, and from 1987 to 1992 he was the chief conductor and then first guest conductor of Orquesta Filarmónica de Gran Canaria.