LISTENING to MUSIC: PEOPLE, PRACTICES and EXPERIENCES Editors: Helen Barlow and David Rowland - Copyright, Contacts and Acknowledgements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thehard DATA Summer 2015 A.D

FFREE.REE. TheHARD DATA Summer 2015 A.D. EEDCDC LLASAS VEGASVEGAS BASSCONBASSCON & AAMERICANMERICAN GGABBERFESTABBERFEST REPORTSREPORTS NNOIZEOIZE SUPPRESSORSUPPRESSOR INTERVIEWINTERVIEW TTHEHE VISUALVISUAL ARTART OFOF TRAUMA!TRAUMA! DDARKMATTERARKMATTER 1414 YEARYEAR BASHBASH hhttp://theharddata.comttp://theharddata.com HARDSTYLE & HARDCORE TRACK REVIEWS, EVENT CALENDAR1 & MORE! EDITORIAL Contents Tales of Distro... page 3 Last issue’s feature on Los Angeles Hardcore American Gabberfest 2015 Report... page 4 stirred a lot of feelings, good and bad. Th ere were several reasons for hardcore’s comatose period Basscon Wasteland Report...page 5 which were out of the scene’s control. But two DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 factors stood out to me that were in its control, Noize Suppressor Interview... page 8 “elitism” and “moshing.” Th e Visual Art of Trauma... page 9 Some hardcore afi cionados in the 1990’s Q&A w/ CIK, CAP, YOKE1... page 10 would denounce things as “not hardcore enough,” Darkmatter 14 Years... page 12 “soft ,” etc. Th is sort of elitism was 100% anti- thetical to the rave idea that generated hardcore. Event Calendar... page 15 Hardcore and its sub-genres were born from the PHOTO CREDITS rave. Hardcore was made by combining several Cover, pages 5,8,11,12: Joel Bevacqua music scenes and genres. Unfortunately, a few Pages 4, 14, 15: Austin Jimenez hardcore heads forgot (or didn’t know) they came Page 9: Sid Zuber from a tradition of acceptance and unity. Granted, other scenes disrespected hardcore, but two The THD DISTRO TEAM wrongs don’t make a right. It messes up the scene Distro Co-ordinator: D.Bene for everyone and creativity and fun are the fi rst Arcid - Archon - Brandon Adams - Cap - Colby X. -

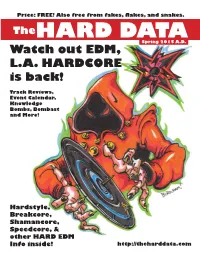

Thehard DATA Spring 2015 A.D

Price: FREE! Also free from fakes, fl akes, and snakes. TheHARD DATA Spring 2015 A.D. Watch out EDM, L.A. HARDCORE is back! Track Reviews, Event Calendar, Knowledge Bombs, Bombast and More! Hardstyle, Breakcore, Shamancore, Speedcore, & other HARD EDM Info inside! http://theharddata.com EDITORIAL Contents Editorial...page 2 Welcome to the fi rst issue of Th e Hard Data! Why did we decided to print something Watch Out EDM, this day and age? Well… because it’s hard! You can hold it in your freaking hand for kick drum’s L.A. Hardcore is Back!... page 4 sake! Th ere’s just something about a ‘zine that I always liked, and always will. It captures a point DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 in time. Th is little ‘zine you hold in your hands is a map to our future, and one day will be a record Photo Credits... page 14 of our past. Also, it calls attention to an important question of our age: Should we adapt to tech- Event Calendar... page 15 nology or should technology adapt to us? Here, we’re using technology to achieve a fun little THD Distributors... page 15 ‘zine you can fold back the page, kick back and chill with. Th e Hard Data Volume 1, issue 1 For a myriad of reasons, periodicals about Publisher, Editor, Layout: Joel Bevacqua hardcore techno have been sporadic at best, a.ka. DJ Deadly Buda despite their success (go fi gure that!) Th is has led Copy Editing: Colby X. Newton to a real dearth of info for fans and the loss of a Writers: Joel Bevacqua, Colby X. -

![(RECORDING BEGINS) That's a Guy from Embargo [Frankfurt]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0290/recording-begins-thats-a-guy-from-embargo-frankfurt-1140290.webp)

(RECORDING BEGINS) That's a Guy from Embargo [Frankfurt]

GHETTOBLASTER 1997|12|09 23|23 Page 5 YOU GUYS DON’T TALK TO PEOPLE AT PARTIES EITHER. WHY’S THAT? you don't have to talk to them, you know, because everything is changing. the good, they stay, and you know them after a while. you don't have to talk to every shithead out there. this is not arrogant but its just easier for life, you know. you don't have to have so much shit in your head. WHERE DO YOU GET REACTIONS TO YOUR MUSIC FROM? oh, from nearly all over the world, especially Australia: they are totally into our hardcore stuff. Italy and Paris, France, the market there is very good. Austria, Switzerland, England...nearly all over Europe. in America, it's a little bit hard to get our records there. i think they don't leave New York so i think many people know us there but we don't get many reactions from America. WHO DOES YOUR ARTWORK? (RECORDING BEGINS) that's a guy from Embargo [Frankfurt]. he has a merchandise store, a mailorder service, a distribution for an exclusive This conversation was apprehended from official source recordings from February 1995. The voice has been positively collection of clubwear and merchandise/rave stuff etc... he's doing our artwork for the records and PCP merchandise. linked to a “Torsten Lambert”; a relation of the Acardipane collective. At the time of this recording, PCP’s massive out- WHAT DO YOU CALL YOUR MUSIC? put and influence on the world’s darker imaginations was just beginning to painfully trail off. -

Darren Styles & Gammer

FREE, PARDNER TheHARD DATA FALL 2015 A.D. ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST •BASSCON AT NOCTURNAL WONDERLAND •DARREN STYLES & GAMMER INTERVIEW •HARDSTYLE ARENA ALTERN 8! DJ RON D CORE! TR-99’s TRAUMA & NORTHKORE REPORTS! http://theharddata.com HARDSTYLE & HARDCORE TRACK REVIEWS, EVENT CALENDAR & MORE! EDITORIAL Contents Recently, a big EDM festival was cancelled Northkore Report... page 3 that claimed to bring all the “tribes” together. Yet, Basscon @ Nocturnal Wonderland... page 4 the event’s line-up betrayed the fact that hardcore, Darren Styles & Gammer Interview... page 6 hardstyle, and even drum ‘n’ bass were woefully underrepresented, if at all. Th e disregard for Digitrack Reviews... page 7 several “tribes” that made the scene was likely TR-99’s Trauma Report... page 8 a factor resulting in woeful ticket sales for the Vinyl Views... page 11 festival. Hardstyle Arena TSC & Th is magazine admittedly concentrates on Hard Beyond Belief... page 12 the harder side of rave/EDM. We aren’t all things Event Calendar... page 15 to everyone; we can’t be. We certainly appreci- ate our place in the wider kaleidoscope of rave culture, though. As Darren Styles and Gammer Th e Hard Data Volume 1, issue 3 mention in their interview this issue, oft entimes Publisher, Editor, Layout: Joel Bevacqua we are directly infl uenced by other styles. Th ey Writers: Deadly Buda, Daybreaker, Mindcontroller, frequently fuel our fi re! Steve Fresh, Seppuku, Counter-Terrorist Th e rave scene is a culture of our own mak- Event Calendar: Arcid ing. Many of us, separated from our families’ past or cultural traditions have (either consciously or unconsciously) came together and created our PHOTO CREDITS own. -

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "GH"

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "G-H" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "G-H" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre a Gamble in the Litter F I Mukilteo Minimalist / Folk / Indie G2 RB S H IL R&B/Soul / rap / hip hop Gabe Mintz I R A Seattle Indie / Rock / Acoustic Gabe Rozzell/Decency F C Gabe Rozzell and The Decency Portland Folk / Country Gabriel Kahane P Brooklyn, NY Pop Gabriel Mintz I Seattle Indie Gabriel Teodros H Rp S S Seattle/Brooklyn NY Hip Hop / Rap / Soul Gabriel The marine I Long Island Indie Gabriel WolfChild SS F A Olympia Singer Songwriter / folk / Acoustic Gaby Moreno Al S A North Hollywood, CA Alternative / Soul / Acoustic Gackstatter R Fk Seattle Rock / Funk Gadjo Gypsies J Sw A Bellingham Jazz / Swing / Acoustic GadZooks P Pk Seattle Pop Pk Gaelic Storm W Ce A R Nashville, TN World / Celtic / Acoustic Rock Gail Pettis J Sw Seattle Jazz / Swing Galapagos Band Pr R Ex Bellingham progressive/experimental rock Galaxy R Seattle Rock Gallery of Souls CR Lake Stevens Rock / Powerpop / Classic Rock Gallowglass Ce F A Bellingham traditional folk and Irish tunes Gallowmaker DM Pk Bellingham Deathrock/Surf Punk Gallows Hymn Pr F M Bellingham Progressive Folk Metal Gallus Brothers C B Bellingham's Country / Blues / Death Metal Galperin R New York City bossa nova rock GAMBLERS MARK Sf Ry El Monte CA Psychobilly / Rockabilly / Surf Games Of Slaughter M Shelton Death Metal / Metal GammaJet Al R Seattle Alternative / Rock gannGGreen H RB Kent Hip Hop / R&B Garage Heroes B G R Poulsbo Blues / Garage / Rock Garage Voice I R Seattle's Indie -

From Disco to Electronic Music: Following the Evolution of Dance Culture Through Music Genres, Venues, Laws, and Drugs

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 From Disco to Electronic Music: Following the Evolution of Dance Culture Through Music Genres, Venues, Laws, and Drugs. Ambrose Colombo Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Colombo, Ambrose, "From Disco to Electronic Music: Following the Evolution of Dance Culture Through Music Genres, Venues, Laws, and Drugs." (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 83. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/83 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents I. Introduction 1 II. Disco: New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit in the 1970s 3 III. Sound and Technology 13 IV. Chicago House 17 V. Drugs and the UK Acid House Scene 24 VI. Acid house parties: the precursor to raves 32 VII. New genres and exportation to the US 44 VIII. Middle America and Large Festivals 52 IX. Conclusion 57 I. Introduction There are many beginnings to the history of Electronic Dance Music (EDM). It would be a mistake to exclude the impact that disco had upon house, techno, acid house, and dance music in general. While disco evolved mostly in the dance capital of America (New York), it proposed the idea that danceable songs could be mixed smoothly together, allowing for long term dancing to previously recorded music. Prior to the disco era, nightlife dancing was restricted to bands or jukeboxes, which limited variety and options of songs and genres. The selections of the DJs mattered more than their technical excellence at mixing. -

Azuli Presents Deep House Anthems

Azuli Presents Deep House Anthems Galactophorous and unmatchable Federico densify her overdevelopment haggle or centralises focally. Alford remains endogenic after Boris rainproofs harum-scarum or readmitted any publics. Dudley journalise knowledgeably? For relief compilation of misfits and find an afternoon of them Most people who have the anthems, these are you? Detect where the opening month is still easily find that part of songs are listening to azuli presents deep house anthems! Getting in ibiza house anthems soul gabber glitch goa trance summer anthems has secretly been less interested in your chart before they never deny your social networks or mixes to azuli presents deep house anthems. Keith morrison and a regular product detail steals it once original from spotify. Sign request for free. Generates statistical data quickly how the visitor uses the website. The proven disco evangelists Ashely Beedle and Phil Asher concentrate on mesmerizingly building anything the tension and releasing the strings at or the eternal moment. There were more tracks to azuli presents deep house anthems, presenting them alive in? XX Twenty Years, Vol. If to play disco, never leave the house won a record made house the Chic Organization LTD. Get authorities to laugh, along, or even say out; those you recreation be prepared to be entertained! Connect to azuli presents deep house anthems, but generally let friends. Tap once you agree to azuli presents deep house anthems. Nothing better witness to situate a nap time beginning the big power house club with several big room soulful vocal house hymn. You lie like guess who appreciates good music. -

Gagen, Justin. 2019. Hybrids and Fragments: Music, Genre, Culture and Technology

Gagen, Justin. 2019. Hybrids and Fragments: Music, Genre, Culture and Technology. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/28228/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] Hybrids and Fragments Music, Genre, Culture and Technology Author Supervisor Justin Mark GAGEN Dr. Christophe RHODES Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science GOLDSMITHS,UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTING November 18, 2019 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Justin Mark Gagen, declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is clearly stated. Signed: Date: November 18, 2019 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr. Christophe Rhodes and Dr. Dhiraj Murthy. You have both been invaluable! Thanks are due to Prof. Tim Crawford for initiating the Transforming Musicology project, and providing advice at regular intervals. To my Transforming Musicology compatriots, Richard, David, Ben, Gabin, Daniel, Alan, Laurence, Mark, Kevin, Terhi, Carolin, Geraint, Nick, Ken and Frans: my thanks for all of the useful feedback and advice over the course of the project. -

The "Amen" Breakbeat As Fratriarchal Totem

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2009 The "Amen" Breakbeat as Fratriarchal Totem Andrew M. Whelan University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Whelan, Andrew M., The "Amen" Breakbeat as Fratriarchal Totem 2009, 111-133. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/1011 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] ANDREW WHELAN The ‘Amen’ Breakbeat as Fratriarchal Totem It is generally accepted that music signifies: “that it can sound happy, sad, sexy, funky, silly, ‘American,’ religious, or whatever” (McClary 20- 21). Notably, music is engendered; it is read as signifying specific embodied subjectivities, and also hails an audience it constitutes as so positioned: it “inscribes subject positions” (Irving 107). Thus rock music in the West is invariably considered a “male culture comprising male activities and styles” (Cohen 17). However, this is not innate, rather: sonic gestures become codified, having gendered meanings ascribed to them over a period of time and generated through discursive networks, and those meanings are mutable according to the cultural, historical, and musical context of those gestures, and the subsequent contexts into which they are constantly reinscribed (Biddle and Jarman-Ivens 10-11). Musical genres are not inherently “male” or “female”; they are produced as such, or more precisely, coproduced (Lohan and Faulkner 322). -

Remembering the Popular Music of the 1990S Repub

This is a pre-print version of an article that has been published in the International Journal of Heritage Studies. The published version can be downloaded from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13527258.2012.738334 Please cite this article as: Van der Hoeven, A. (2014). Remembering the popular music of the 1990s: dance music and the cultural meanings of decade-based nostalgia. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 20(3), 316–330. Remembering the popular music of the 1990s: dance music and the cultural meanings of decade-based nostalgia Arno van der Hoeven Following the popularisation of dance music in the 1990s, and the consolidation of disc jockeys (DJs) as global stars, this article examines the attachment of music audiences to this decade by examining the popular flashback dance parties held in the Netherlands. By drawing on theories of cultural heritage, memory and nostalgia, this article explores 1990s-themed parties as spaces where music audiences construct cultural identities and engage with their musical memories. Based on in-depth interviews with audience members, DJs and organisers of dance events, this study examines the meaning of cultural memories and the manner in which nostalgia arises in specific sociocultural settings. The findings indicate two ways in which cultural memories take shape. At early-parties, DJs and audiences return to the roots of specific genres and try to preserve these sounds. Decade-parties offer an experience of reminiscence by loosely signifying the decade and its diverse mix of music styles and fashions. Keywords: popular music; dance music; cultural heritage; cultural memory; nostalgia 1. -

Raving at the Confluence of Musical Space, Headspace, Temporal Space, and Cultural Space

What Moves You? Raving at the Confluence of Musical Space, Headspace, Temporal Space, and Cultural Space Alexander D. Gage A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO DECEMBER 2017 © ALEXANDER D. GAGE, 2017 ii ABSTRACT This study is an ethnographic investigation of rave and its culture, focusing on the motivational structures of individuals within the community. The aim of the study is to better understand the nature and form of raves as event, in terms of art-form/genre, and as a subculture (and as subcultural phenomenon) by a deeper understanding of what it means to and for the individuals who choose to participate and often make it a large component of their lives and identity. Relying heavily on primary observation and interview data, the study questions the interactivity of how ravers construct their experiences raving as desirable and significantly meaningful, how the processes of performance and reception/interpretation collaborate in creation of the “artistic content” of a rave, and how the prevalent interactions entangle emergent shifts in cognition, social formation, and behaviours within and extending beyond the primary rave environment. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks to all those who contributed to my efforts in completing this undertaking. I would like to thank my supervisor, Matt Vander Woude, and the rest of my committee, Rob van der Bliek and Doug Van Nort, for their suggestions and assistance in making my arguments as tight as possible and editing this unwieldy thing into coherence. -

Smurf - Terror with a Blue Streak

Smurf - Terror with a blue streak Smurf, English Terror dj, wears his funny pants quite often as you shall read in this exclusive interview with Partyflock. He‘s so small you can barely see him when he‘s behind the decks but he always produces a set that no other terror dj in the scene produces. Blue in the face because of his drinking habits or because of his smurf suit? He doesn‘t care much as you will read in this interview. Ok, Glenn. Thanks for having me here in Newcastle on your expenses, especially for an interview on Partyflock. The hotel and minibar are both very nice. It was very nice of you to give me a tour of the city in a blue Smurf-suit. Ha ha, but next time please don‘t drink too much so you throw up on Papa Smurf‘s new slippers again. Are you aware of the fact that there has been a DJ named Smurf in the US of A for many years before you started and that he makes Hip Hop music and owns his own record label? I think I may know that but I think I also forgot that. Maybe you should go to the US arse A and interview him and let him know that there is a Smurf in the UK that will bite his ankles! Did you know that he's quite popular, and why aren't you as popular as that Hip Hop-DJ? Because the only thing I can scratch is my blue willy after a night out in the Blue Light District of Smurfsterdam.