Raving at the Confluence of Musical Space, Headspace, Temporal Space, and Cultural Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electro House 2015 Download Soundcloud

Electro house 2015 download soundcloud CLICK TO DOWNLOAD TZ Comment by Czerniak Maciek. Lala bon. TZ Comment by Czerniak Maciek. Yeaa sa pette. TZ. Users who like Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix ; Users who reposted Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix ; Playlists containing Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix Electro House by EDM Joy. Part of @edmjoy. Worldwide. 5 Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Electro House @ EDM Joy on your desktop or mobile device. An icon used to represent a menu that can be toggled by interacting with this icon. Best EDM Remixes Of Popular Songs - New Electro & House Remix; New Electro & House Best Of EDM Mix; New Electro & House Music Dance Club Party Mix #5; New Dirty Party Electro House Bass Ibiza Dance Mix [ FREE DOWNLOAD -> Click "Buy" ] BASS BOOSTED CAR MUSIC MIX BEST EDM, BOUNCE, ELECTRO HOUSE. FREE tracks! PLEASE follow and i will continue to post songs:) ALL CREDIT GOES TO THE PRODUCERS OF THE SONG, THIS PAGE IS FOR PROMOTIONAL USE ONLY I WILL ONLY POST SONGS THAT ARE PUT UP FOR FREE. 11 Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Free Electro House on your desktop or mobile device. Listen to the best DJs and radio presenters in the world for free. Free Download Music & Free Electronic Dance Music Downloads and Free new EDM songs and tracks. Get free Electro, House, Trance, Dubstep, Mixtape downloads. Exclusive download New Electro & House Best of Party Mashup, Bootleg, Remix Dance Mix Click here to download New Electro & House Best of Party Mashup, Bootleg, Remix Dance Mix Maximise Network, Eric Clapman and GANGSTA-HOUSE on Soundcloud Follow +1 entry I've already followed Maximise Music, Repost Media, Maximise Network, Eric. -

The Normal Heart

THE NORMAL HEART Written By Larry Kramer Final Shooting Script RYAN MURPHY TELEVISION © 2013 Home Box Office, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Home Box Office. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions previously set forth. 1 EXT. APPROACHING FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 1 Masses of beautiful men come towards the camera. The dock is full and the boat is packed as it disgorges more beautiful young men. NED WEEKS, 40, with his dog Sam, prepares to disembark. He suddenly puts down his bag and pulls off his shirt. He wears a tank-top. 2 EXT. HARBOR AT FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 2 Ned is the last to disembark. Sam pulls him forward to the crowd of waiting men, now coming even closer. Ned suddenly puts down his bag and puts his shirt back on. CRAIG, 20s and endearing, greets him; they hug. NED How you doing, pumpkin? CRAIG We're doing great. 3 EXT. BRUCE NILES'S HOUSE. FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 3 TIGHT on a razor shaving a chiseled chest. Two HANDSOME guys in their 20s -- NICK and NINO -- are on the deck by a pool, shaving their pecs. They are taking this very seriously. Ned and Craig walk up, observe this. Craig laughs. CRAIG What are you guys doing? NINO Hairy is out. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

It's a Wonderful Life

It’s a Wonderful Life KIOWA COUNTY 4 Watch the Table of Contents Movie Online 2 Reflections on a Small Town 4 Becoming George Bailey Three Journeys to One 10 Destination Three Poems by Two 14 Campbells 16 The Signature of a Life 22 Rural Free Delivery Holiday Tournament Defines 24 Christmas in Southeast CO 28 Eva’s Christmas Story “You see, George, you really 30 do have a wonderful life” Kiowa County Independent Publisher Betsy Barnett Advertising Cindy McLoud 1316 Maine Street Editor Priscilla Waggoner Web Page Kayla Murdock PO Box 272 Layout and Design William Brandt Distribution Denise Nelson Eads, CO 81036 Advertising John Contreras Special thanks to Sherri Mabe for use of [email protected] her photos: sherrimabeimages.com. Kiowa Countykiowacountyindependent.com Independent © December 2018 It’s a Wonderful Life | 1 ne morning not long ago, a prominent, local are, nonetheless, the things he does. What he is… man came into the newspaper office. He’s is a thinker. And he’d clearly been thinking about Odone that a few times before. He might be something that morning because he clearly had on his way to Denver, or he might have come to something to say. town on business. Whatever the circumstance or, “I’ve been all around the world,” he began. he’s stopped by the office just to say hello, just to “Russia. Asia. All sorts of different places in Eu- make sure we’re continuing to do what we do and, rope—I’ve been there. I’ve been very lucky to sometimes, just to let us know he’s glad we’re do- have opportunities present themselves that just ing it. -

M I K E S a R K I S S I a N Credits

MIKE SARKISSIAN CREDITS _____________________________________________________________________________ EXECUTIVE PRODUCER / PRODUCER FILM The White Stripes Under Great White Northern Lights Emmett Malloy Jack Johnson En Concert Emmett Malloy Jack Johnson A Weekend at the Greek Emmett Malloy Jack White Jack White Kneeling at The Anthem Emmett Malloy TV Paramount Dream: Birth of the Modern Athlete The Malloy Brothers National Geographic Breakthrough Season 2 Series Producer Revolution Studios Pilot – Everyday People Tim Wheeler GSN / Revolution Studios Drew Carey’s Improv-A-ganza 40 eps Liz Zannin The Dead Weather Live at the ROXY Tim Wheeler Jack Johnson Kokua Festival 05-09 Emmett Malloy From The Basement Raconteurs / Kills / Fleet Foxes Nigel Godrich From The Basement Queens of the Stone Age Nigel Godrich Sundance Channel 5 Years of Change – KOKUA Emmett Malloy Selena Gomez Girl Meets World – Disney Channel Tim Wheeler James Blunt Live & SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler Disney Channel Radio Disney Concert Special Tim Wheeler Nickelback Live at Home Nigel Dick Marie Digby Live At Rick Ruben Studios Mike Piscitelli Grace Potter Live In Burlington Tim Wheeler Alpha Rev Live @SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler Kate Vogel Live @SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler ZZ Ward Live @ The Troubadour Tim Wheeler Nick Jonas Live @ Capitol Records Giles Dunning Grace Potter Live @ The Waterfront Tim Wheeler R5 Live @ the O2 London Tim Wheeler COMMERCIALS Honda Happy Honda Days ’19 Campain Jed Hathaway Apple Apple TV+ 2019 March Launch Robin Cosimir Waze Waze Carpool Jeff + Pete Accenture Talent, Resilience, Disruption Jordan Bahat Google Google Cloud Jordan Bahat Amazon Fire TV Twin Peaks Pie Shop, Playlist Jeff + Pete Always Prepared, No Chance Whip It, Whip it Good Sharknado by the Sea Chicken Little Fingers Dove Real Moms Acura Emotion Is In IBM / Watson Not Easy Nicolas Davenel Max Factor Miracle Touch Camilla Akrins Visa Snapchat / Olympics Giles Dunning McDonalds Fans vs Critics Jordan Bahat Navy Federal Credit Union Veterans Bond Jeff + Pete Dr. -

PDF Transcript of This Episode Here

Medicine Stories Podcast Episode 35 with Alela Diane Giving Life to Songs and Babies December 18, 2018 [0:00:00] (Excerpt from today’s show by Alela Diane) What I experienced, and I’m sure what you experienced with your mom’s loss and getting pregnant with Nixie shortly thereafter, is how intertwined the connection between birth and death are. Those experiences are so linked in a really beautiful and spooky and magical way I think. [0:00:22] (Intro Music: acoustic guitar folk song "Wild Eyes" by Mariee Sioux) Amber: Hello and welcome! I am Amber Magnolia Hill, and this is Medicine Stories, where we are exploring what it is to be human upon the earth through interviews that center on ancestry, herbalism, myth, mind, and magic. And sometimes we dive into motherhood, as well, as in today’s podcast with Alela Diane. And music! Myth, mind, motherhood, and music. Alela and I talk about: ● Her unique name, her feral childhood, and her deeply rooted familial musical inheritance ● The painful life experiences that led Alela to start making music ● Songs that come in dreams, or that contain premonitions or foreknowledge of the future ● And then we move into talking about motherhood and the intersection of motherhood and work and creativity ● We talk about touring as a mom (taking them with and leaving them home) ● Our experiences of weaning our two daughters; we both have two girls ● Alela tells the whole story of how she almost lost her life bringing her second daughter into the world, giving her second daughter her life ● And then we close with a little story about how she knew when her grandmother had passed. -

Züritipp Clap Your Hands Say Yeah

MATCH & FUSE FESTIVAL 23 FUSION Das Festival bringt Musiker aus verschiedenen Genres zusammen. VON FRANK VON NIEDERHÄUSERN JAZZ Viele Jung-Jazzer fressen heute begierig über die stilistischen Gartenzäune. Kein Wunder, dass der Aus- tausch zwischen den Szenen heute intensiver geschieht denn je. Das Label Match & Fuse gibt solchen Interak- tionen seit fünf Jahren Zusatzschub und lädt zu inter- nationalen Festivals. Diesmal nach Zürich. In den Clubs Moods, Exil, Mehrspur und Laborbar stehen zwölf Kon- zerte an, die das Publikum hellhörig und die Musizie- renden inspirieren sollen. Aus hiesigen Küchen melden sich das wagemutig-hybride Elektro-Akustik-Trio Me & Mobi, die Tüftel-WG Schnellertollermeier oder Sängerin Lucia Cadotsch mit gleich zwei Varianten ihres Projekts Speak Low. Zu entdecken ist Drummer-Sän- gerin Siv Øyunn aus Oslo oder das französische Synth- Drummer-Duo In Girum mit Plaistow-Pianist Johann Die Wilde mags auch kuschelig. Bourquenez. Hoffentlich nicht zu sehr. DO BIS SA — 2000 DIVERSE ORTE BETH DITTO / Konzerte Musik MOODS / ZHDK / EXIL / LABORBAR WWW.MATCHANDFUSE.CH Eintritt 35 Franken WACHRÜTTLERIN CLAP YOUR Die Sängerin, die mit der Gruppe Gossip HANDS SAY YEAH berühmt wurde, hat eine Solokarriere eingeschlagen. Ihre Musik ist heute unauffälliger. VON ADRIAN SCHRÄDER POP Die Wucht ist weg. Gossip gibt es nicht Jennifer Decilveo hat sie über weite Strecken GUTE NUMMER mehr. Die Band, der wir Songs wie «Heavy ein Südstaatenpop-Album aufgenommen — 4.10.2017 28.9. Cross» oder «Coal to Diamonds» zu ver- – gespickt mit leisen Referenzen an die Sieb- INDIE Dreihundert Alben will die amerikanische Band danken haben, hat sich Anfang 2016 auf- ziger und Achtziger, mit Ausflügen in Soul, Clap Your Hands Say Yeah insgesamt veröffentlichen. -

Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews На Arrhythmia Sound

2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound Home Content Contacts About Subscribe Gallery Donate Search Interviews Reviews News Podcasts Reports Home » Reviews Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) Submitted by: Quarck | 19.04.2008 no comment | 198 views Aaron Spectre , also known for the project Drumcorps , reveals before us completely new side of his work. In protovoves frenzy breakgrindcore Specter produces a chic downtempo, idm album. Lost Tracks the result of six years of work, but despite this, the rumor is very fresh and original. The sound is minimalistic without excesses, but at the same time the melodies are very beautiful, the bit powerful and clear, pronounced. Just want to highlight the composition of Break Ya Neck (Remix) , a bit mystical and mysterious, a feeling, like wandering somewhere in the http://www.arrhythmiasound.com/en/review/aaron-spectre-lost-tracks-ad-noiseam-2007.html 1/3 2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound dusk. There was a place and a vocal, in a track Degrees the gentle voice Kazumi (Pink Lilies) sounds. As a result, Lost Tracks can be safely put on a par with the works of such mastadonts as Lusine, Murcof, Hecq. Tags: downtempo, idm Subscribe Email TOP-2013 Submit TOP-2014 TOP-2015 Tags abstract acid ambient ambient-techno artcore best2012 best2013 best2014 best2015 best2016 best2017 breakcore breaks cyberpunk dark ambient downtempo dreampop drone drum&bass dub dubstep dubtechno electro electronic experimental female vocal future garage glitch hip hop idm indie indietronica industrial jazzy krautrock live modern classical noir oldschool post-rock shoegaze space techno tribal trip hop Latest The best in 2017 - albums, places 1-33 12/30/2017 The best in 2017 - albums, places 66-34 12/28/2017 The best in 2017. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Thehard DATA Summer 2015 A.D

FFREE.REE. TheHARD DATA Summer 2015 A.D. EEDCDC LLASAS VEGASVEGAS BASSCONBASSCON & AAMERICANMERICAN GGABBERFESTABBERFEST REPORTSREPORTS NNOIZEOIZE SUPPRESSORSUPPRESSOR INTERVIEWINTERVIEW TTHEHE VISUALVISUAL ARTART OFOF TRAUMA!TRAUMA! DDARKMATTERARKMATTER 1414 YEARYEAR BASHBASH hhttp://theharddata.comttp://theharddata.com HARDSTYLE & HARDCORE TRACK REVIEWS, EVENT CALENDAR1 & MORE! EDITORIAL Contents Tales of Distro... page 3 Last issue’s feature on Los Angeles Hardcore American Gabberfest 2015 Report... page 4 stirred a lot of feelings, good and bad. Th ere were several reasons for hardcore’s comatose period Basscon Wasteland Report...page 5 which were out of the scene’s control. But two DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 factors stood out to me that were in its control, Noize Suppressor Interview... page 8 “elitism” and “moshing.” Th e Visual Art of Trauma... page 9 Some hardcore afi cionados in the 1990’s Q&A w/ CIK, CAP, YOKE1... page 10 would denounce things as “not hardcore enough,” Darkmatter 14 Years... page 12 “soft ,” etc. Th is sort of elitism was 100% anti- thetical to the rave idea that generated hardcore. Event Calendar... page 15 Hardcore and its sub-genres were born from the PHOTO CREDITS rave. Hardcore was made by combining several Cover, pages 5,8,11,12: Joel Bevacqua music scenes and genres. Unfortunately, a few Pages 4, 14, 15: Austin Jimenez hardcore heads forgot (or didn’t know) they came Page 9: Sid Zuber from a tradition of acceptance and unity. Granted, other scenes disrespected hardcore, but two The THD DISTRO TEAM wrongs don’t make a right. It messes up the scene Distro Co-ordinator: D.Bene for everyone and creativity and fun are the fi rst Arcid - Archon - Brandon Adams - Cap - Colby X. -

Thehard DATA Spring 2015 A.D

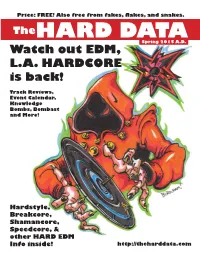

Price: FREE! Also free from fakes, fl akes, and snakes. TheHARD DATA Spring 2015 A.D. Watch out EDM, L.A. HARDCORE is back! Track Reviews, Event Calendar, Knowledge Bombs, Bombast and More! Hardstyle, Breakcore, Shamancore, Speedcore, & other HARD EDM Info inside! http://theharddata.com EDITORIAL Contents Editorial...page 2 Welcome to the fi rst issue of Th e Hard Data! Why did we decided to print something Watch Out EDM, this day and age? Well… because it’s hard! You can hold it in your freaking hand for kick drum’s L.A. Hardcore is Back!... page 4 sake! Th ere’s just something about a ‘zine that I always liked, and always will. It captures a point DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 in time. Th is little ‘zine you hold in your hands is a map to our future, and one day will be a record Photo Credits... page 14 of our past. Also, it calls attention to an important question of our age: Should we adapt to tech- Event Calendar... page 15 nology or should technology adapt to us? Here, we’re using technology to achieve a fun little THD Distributors... page 15 ‘zine you can fold back the page, kick back and chill with. Th e Hard Data Volume 1, issue 1 For a myriad of reasons, periodicals about Publisher, Editor, Layout: Joel Bevacqua hardcore techno have been sporadic at best, a.ka. DJ Deadly Buda despite their success (go fi gure that!) Th is has led Copy Editing: Colby X. Newton to a real dearth of info for fans and the loss of a Writers: Joel Bevacqua, Colby X. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here..