Quantifying Music Trends and Facts Using Editorial Metadata from the Discogs Database

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electro House 2015 Download Soundcloud

Electro house 2015 download soundcloud CLICK TO DOWNLOAD TZ Comment by Czerniak Maciek. Lala bon. TZ Comment by Czerniak Maciek. Yeaa sa pette. TZ. Users who like Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix ; Users who reposted Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix ; Playlists containing Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix Electro House by EDM Joy. Part of @edmjoy. Worldwide. 5 Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Electro House @ EDM Joy on your desktop or mobile device. An icon used to represent a menu that can be toggled by interacting with this icon. Best EDM Remixes Of Popular Songs - New Electro & House Remix; New Electro & House Best Of EDM Mix; New Electro & House Music Dance Club Party Mix #5; New Dirty Party Electro House Bass Ibiza Dance Mix [ FREE DOWNLOAD -> Click "Buy" ] BASS BOOSTED CAR MUSIC MIX BEST EDM, BOUNCE, ELECTRO HOUSE. FREE tracks! PLEASE follow and i will continue to post songs:) ALL CREDIT GOES TO THE PRODUCERS OF THE SONG, THIS PAGE IS FOR PROMOTIONAL USE ONLY I WILL ONLY POST SONGS THAT ARE PUT UP FOR FREE. 11 Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Free Electro House on your desktop or mobile device. Listen to the best DJs and radio presenters in the world for free. Free Download Music & Free Electronic Dance Music Downloads and Free new EDM songs and tracks. Get free Electro, House, Trance, Dubstep, Mixtape downloads. Exclusive download New Electro & House Best of Party Mashup, Bootleg, Remix Dance Mix Click here to download New Electro & House Best of Party Mashup, Bootleg, Remix Dance Mix Maximise Network, Eric Clapman and GANGSTA-HOUSE on Soundcloud Follow +1 entry I've already followed Maximise Music, Repost Media, Maximise Network, Eric. -

Funkids Amb La Black Music Big Band & Brodas Junior

Dossier pedagògic — FunKids amb la Black Music Big Band Dossier pedagògic FunKids amb la Black Music Big Band & Brodas Junior Auditori de Girona Dossier pedagògic — FunKids amb la Black Music Big Band —3 Presentació —4 Fitxa artística —5 Black Music Big Band- BMBB —6 Què és una Big Band: una gran orquestra de jazz —7 Ball urbà — 2 Dossier pedagògic — FunKids amb la Black Music Big Band Presentació Qui no es mou amb la música funky? La proposta fresca Un espectacle i rítmica de l’Auditori Obert, en què els alumnes desco- briran l’essència de la música negra amb el funky i el soul amb més de 45 com a protagonistes. Un concert formatiu sobre la Big participants dalt Band, els seus instruments i estil amb explicacions en català i pinzellades en anglès (fàcilment comprensibles de l’escenari per als nens i nenes). Tot plegat de la mà dels joves de la entre músics i BMBB i al costat dels ballarins de Brodas Junior, que fa- ballarins ran del FunKids un concert ple d’espectacularitat i ritme! Qui no es mou amb la música funky? Arriba una proposta fresca i rítmica de l’Auditori Obert, en la qual els més joves descobriran l’essència de la música negra amb el funky i el soul com a protagonistes. Un concert formatiu i pedagògic que ens parlarà de la Big Band, els seus instru- ments i estil, el mon del ball urbà, etc.... Què podrem conèixer a FunKids? - Els seus instruments: secció de saxos, trompetes, trombons i la base rítmica - Escoltarem les diferents veus de la Black Music - Viurem els diferents estils de balls urbans com el locking, el popping, el bboying o el hiphop I tot això amb explicacions en català i pinzellades en anglès. -

The Kid3 Handbook

The Kid3 Handbook Software development: Urs Fleisch The Kid3 Handbook 2 Contents 1 Introduction 11 2 Using Kid3 12 2.1 Kid3 features . 12 2.2 Example Usage . 12 3 Command Reference 14 3.1 The GUI Elements . 14 3.1.1 File List . 14 3.1.2 Edit Playlist . 15 3.1.3 Folder List . 15 3.1.4 File . 16 3.1.5 Tag 1 . 17 3.1.6 Tag 2 . 18 3.1.7 Tag 3 . 18 3.1.8 Frame List . 18 3.1.9 Synchronized Lyrics and Event Timing Codes . 21 3.2 The File Menu . 22 3.3 The Edit Menu . 28 3.4 The Tools Menu . 29 3.5 The Settings Menu . 32 3.6 The Help Menu . 37 4 kid3-cli 38 4.1 Commands . 38 4.1.1 Help . 38 4.1.2 Timeout . 38 4.1.3 Quit application . 38 4.1.4 Change folder . 38 4.1.5 Print the filename of the current folder . 39 4.1.6 Folder list . 39 4.1.7 Save the changed files . 39 4.1.8 Select file . 39 4.1.9 Select tag . 40 The Kid3 Handbook 4.1.10 Get tag frame . 40 4.1.11 Set tag frame . 40 4.1.12 Revert . 41 4.1.13 Import from file . 41 4.1.14 Automatic import . 41 4.1.15 Download album cover artwork . 42 4.1.16 Export to file . 42 4.1.17 Create playlist . 42 4.1.18 Apply filename format . 42 4.1.19 Apply tag format . -

Songkong for Melco

Digital Music Metadata SongKong Music Tagger Automatically managing your music metadata Digitized Music Library - Problems • Different mechanisms used to rip or download music • Music stored in different audio formats • Music collections much larger than before • Quality of original metadata varies considerably • No comprehensive metadata standard • Manually adding metadata very time consuming • Impossible to keep metadata consistent as add to collection SongKong - Concept • Should be possible to automatch and add metadata for majority of music collection easily • Need to apply consistency over collection, and keep consistent • Fix metadata within files so customer not tied to a particular music player (iTunes/Roon, Naim Wav Metadata) • Need rich comprehensive metadata, simple album/artist/title not enough • But need to give customer enough control because there is no such thing as a single one-fit metadata solution • Music collections are valuable and personal so we need • An audit of what has changed • Ability to undo changes if we don’t like them SongKong Music Tagger Installation • Available for: • Windows • MacOS • Linux • Synology Disk Station • Qnap Nas • Melco N1 Audio Server • Desktop and Remote interface for Windows/MacOS, Linux Desktop • Remote Web Interface for others so can be controlled from web browser even on iPad or phone Three steps to Improved Metadata 1. Select your Music folder and Run Fix Songs task. 2. Review the Options, then press Start 3. Wait for completion, detailed report shows exactly what has changed 1. Select your Music folder and Run Fix Songs task 2. Review any Options, e.g Basic Options Format Options (Desktop view) Classical Options (Web Browser View) . -

Release 3.5.3

Ex Falso / Quod Libet Release 3.5.3 February 02, 2016 Contents 1 Table of Contents 3 i ii Ex Falso / Quod Libet, Release 3.5.3 Note: There exists a newer version of this page and the content below may be outdated. See https://quodlibet.readthedocs.org/en/latest for the latest documentation. Quod Libet is a GTK+-based audio player written in Python, using the Mutagen tagging library. It’s designed around the idea that you know how to organize your music better than we do. It lets you make playlists based on regular expressions (don’t worry, regular searches work too). It lets you display and edit any tags you want in the file, for all the file formats it supports. Unlike some, Quod Libet will scale to libraries with tens of thousands of songs. It also supports most of the features you’d expect from a modern media player: Unicode support, advanced tag editing, Replay Gain, podcasts & Internet radio, album art support and all major audio formats - see the screenshots. Ex Falso is a program that uses the same tag editing back-end as Quod Libet, but isn’t connected to an audio player. If you’re perfectly happy with your favorite player and just want something that can handle tagging, Ex Falso is for you. Contents 1 Ex Falso / Quod Libet, Release 3.5.3 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Table of Contents Note: There exists a newer version of this page and the content below may be outdated. See https://quodlibet.readthedocs.org/en/latest for the latest documentation. -

The THREE's a CROWD

The THREE’S A CROWD exhibition covers areas ranging from Hong Kong to Slavic vixa parties. It looks at modern-day streets and dance floors, examining how – through their physical presence in the public space – bodies create temporary communities, how they transform the old reality and create new conditions. And how many people does it take to make a crowd. The autonomous, affect-driven and confusing social body is a dynamic 19th-century construct that stands in opposition to the concepts of capitalist productivity, rationalism, and social order. It is more of a manifestation of social dis- order: the crowd as a horde, the crowd as a swarm. But it happens that three is already a crowd. The club culture remembers cases of criminalizing the rhythmic movement of at least three people dancing to the music based on repetitive beats. We also remember this pandemic year’s spring and autumn events, when the hearts of the Polish police beat faster at the sight of crowds of three and five people. Bodies always function in relation to other bodies. To have no body is to be nobody. Bodies shape social life in the public space through movement and stillness, gath- ering and distraction. Also by absence. Regardless of whether it is a grassroots form of bodily (dis)organization, self-cho- reographed protests, improvised social dances, artistic, activist or artivist actions, bodies become a field of social and political struggle. Together and apart. ARTISTS: International Festival of Urban ARCHIVES OF PUBLIC Art OUT OF STH VI: SPACE PROTESTS ABSORBENCY -

Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews На Arrhythmia Sound

2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound Home Content Contacts About Subscribe Gallery Donate Search Interviews Reviews News Podcasts Reports Home » Reviews Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) Submitted by: Quarck | 19.04.2008 no comment | 198 views Aaron Spectre , also known for the project Drumcorps , reveals before us completely new side of his work. In protovoves frenzy breakgrindcore Specter produces a chic downtempo, idm album. Lost Tracks the result of six years of work, but despite this, the rumor is very fresh and original. The sound is minimalistic without excesses, but at the same time the melodies are very beautiful, the bit powerful and clear, pronounced. Just want to highlight the composition of Break Ya Neck (Remix) , a bit mystical and mysterious, a feeling, like wandering somewhere in the http://www.arrhythmiasound.com/en/review/aaron-spectre-lost-tracks-ad-noiseam-2007.html 1/3 2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound dusk. There was a place and a vocal, in a track Degrees the gentle voice Kazumi (Pink Lilies) sounds. As a result, Lost Tracks can be safely put on a par with the works of such mastadonts as Lusine, Murcof, Hecq. Tags: downtempo, idm Subscribe Email TOP-2013 Submit TOP-2014 TOP-2015 Tags abstract acid ambient ambient-techno artcore best2012 best2013 best2014 best2015 best2016 best2017 breakcore breaks cyberpunk dark ambient downtempo dreampop drone drum&bass dub dubstep dubtechno electro electronic experimental female vocal future garage glitch hip hop idm indie indietronica industrial jazzy krautrock live modern classical noir oldschool post-rock shoegaze space techno tribal trip hop Latest The best in 2017 - albums, places 1-33 12/30/2017 The best in 2017 - albums, places 66-34 12/28/2017 The best in 2017. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

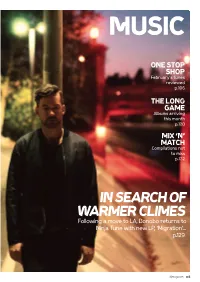

IN SEARCH of WARMER CLIMES Following a Move to LA, Bonobo Returns to Ninja Tune with New LP, ‘Migration’

MUSIC ONE STOP SHOP February’s tunes reviewed p.106 THE LONG GAME Albums arriving this month p.128 MIX ‘N’ MATCH Compilations not to miss p.132 IN SEARCH OF WARMER CLIMES Following a move to LA, Bonobo returns to Ninja Tune with new LP, ‘Migration’... p.129 djmag.com 105 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Roberto Clementi Avesys EP [email protected] Pets Recordings 8.0 Sheer class from Roberto Clementi on Pets. The title track is brooding and brilliant, thick with drama, while 'Landing A Man'’s relentless thump betrays a soft and gentle side. Lovely. Jagwar Ma Give Me A Reason (Michael Mayer Does The Amoeba Remix) Marathon MONEY 8.0 SHOT! Showing that he remains the master (and managing Baba Stiltz to do so in under seven minutes too), Michael Mayer Is Everything smashes this remix of baggy dance-pop dudes Studio Barnhus Jagwar Ma out of the park. 9.5 The unnecessarily young Baba Satori Stiltz (he's 22) is producing Imani's Dress intricate, brilliantly odd house Crosstown Rebels music that bearded weirdos 8.0 twice his age would give their all chopped hardcore loops, and a brilliance from Tact Recordings Crosstown is throwing weight behind the rather mid-life crises for. Think the bouncing bassline. Sublime work. comes courtesy of roadman (the unique sound of Satori this year — there's an album dizzying brilliance of Robag small 'r' is intentional), aka coming — but ignore the understatedly epic Ewan Whrume for a reference point, Dorsia Richard Fletcher. He's also Tact's Pearson mixes of 'Imani's Dress' at your peril. -

Navigating Noise Means Getting Off the Beaten Track in Order to Find, Or Rather, to Create Something New

Navigating Noise means getting off the beaten track in order to find, or rather, to create something new. This publication is the result of such unconventional navigations, which follow the track of noise on its path across art, science, and the humanities. The point of departure is the artwork Navigating Navigating Noise by Kerstin Ergenzinger. This ephemeral, somewhat Navigating out-worldly sound installation provides the framework for a collection of academic and artistic contributions that address the need for alternative means of orientation to deal with noise and to understand and (re)establish our unstable position within a highly technologized, mediated, and globalized reality. These navigations cover a broad terrain of research: from the starry skies to the deep oceans, from the ice cores of Greenland to sonic navigation in the animal kingdom, from spatial acoustics in World War I to noise music. Through a multidisciplinary approach, Navigating Noise paves the way for unexpected connections between research domains located at the border of knowing and not knowing. This endeavour tries to dig through and below existing semantic and epistemic systems. The contributors scrutinize the binary dichotomies of noise/information, noise/meaning, and noise/silence in order to reconfigure the relational framework that is constituted by these dichotomies. Released from this, noise no longer serves as the unwanted, semantic-free, and inefficient antithesis Noise that should be discarded, but rather embodies a dynamic, unpredictable, yet constitutive force with which we can soar towards more agile forms of sonic sense production. Noise Noise is the dynamic condition of the possibility for any form of meaning. -

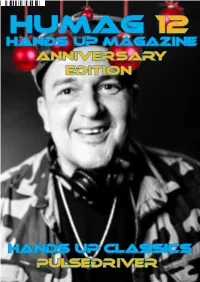

Hands up Classics Pulsedriver Hands up Magazine Anniversary Edition

HUMAG 12 Hands up Magazine anniversary Edition hANDS Up cLASSICS Pulsedriver Page 1 Welcome, The time has finally come, the 12th edition of the magazine has appeared, it took a long time and a lot has happened, but it is done. There are again specials, including an article about pulsedriver, three pages on which you can read everything that has changed at HUMAG over time and how the de- sign has changed, one page about one of the biggest hands up fans, namely Gabriel Chai from Singapo- re, who also works as a DJ, an exclusive interview with Nick Unique and at the locations an article about Der Gelber Elefant discotheque in Mühlheim an der Ruhr. For the first time, this magazine is also available for download in English from our website for our friends from Poland and Singapore and from many other countries. We keep our fingers crossed Richard Gollnik that the events will continue in 2021 and hopefully [email protected] the Easter Rave and the TechnoBase birthday will take place. Since I was really getting started again professionally and was also ill, there were unfortu- nately long delays in the publication of the magazi- ne. I apologize for this. I wish you happy reading, Have a nice Christmas and a happy new year. Your Richard Gollnik Something Christmas by Marious The new Song Christmas Time by Mariousis now available on all download portals Page 2 content Crossword puzzle What is hands up? A crossword puzzle about the An explanation from Hands hands up scene with the chan- Up. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC).