The "Amen" Breakbeat As Fratriarchal Totem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Bass

First published by Velocity Press 2020 velocitypress.uk Copyright © Martin James 2020 Cover design: Designment designment.studio Typesetting: Paul Baillie-Lane pblpublishing.co.uk Photography: Cleveland Aaron, Andy Cotterill, Courtney Hamilton, Tristan O’Neill Martin James has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identied as the author of this work All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission from the publisher While the publishers have made every reasonable eort to trace the copyright owners for some of the photographs in this book, there may be omissions of credits, for which we apologise. ISBN: 9781913231026 1: Ag’A THE JUNGLISTS NAMING THE SOUND, LOCATING THE SCENE ‘It always has been such a terrible name. I’ve never known any other type of music to get so misconstrued by its name.’ (Rob Playford, 1996) Of all of the dance music genres, none has been surrounded with quite so much controversy over its name than jungle. No sooner had it been coined than exponents of the scene were up in arms about the racist implications. Arguments raged over who rst used the term and many others simply refused to acknowledge the existence of the moniker. It wasn’t the rst time that jungle had been used as a way to describe a sound. Kool and the Gang had called their 1973 funk standard Jungle Boogie, while an instrumental version with an overdubbed ute part and additional percussion instruments was titled Jungle Jazz. The song ends with a Tarzan yell and features grunting, panting and scatting throughout. -

Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews На Arrhythmia Sound

2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound Home Content Contacts About Subscribe Gallery Donate Search Interviews Reviews News Podcasts Reports Home » Reviews Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) Submitted by: Quarck | 19.04.2008 no comment | 198 views Aaron Spectre , also known for the project Drumcorps , reveals before us completely new side of his work. In protovoves frenzy breakgrindcore Specter produces a chic downtempo, idm album. Lost Tracks the result of six years of work, but despite this, the rumor is very fresh and original. The sound is minimalistic without excesses, but at the same time the melodies are very beautiful, the bit powerful and clear, pronounced. Just want to highlight the composition of Break Ya Neck (Remix) , a bit mystical and mysterious, a feeling, like wandering somewhere in the http://www.arrhythmiasound.com/en/review/aaron-spectre-lost-tracks-ad-noiseam-2007.html 1/3 2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound dusk. There was a place and a vocal, in a track Degrees the gentle voice Kazumi (Pink Lilies) sounds. As a result, Lost Tracks can be safely put on a par with the works of such mastadonts as Lusine, Murcof, Hecq. Tags: downtempo, idm Subscribe Email TOP-2013 Submit TOP-2014 TOP-2015 Tags abstract acid ambient ambient-techno artcore best2012 best2013 best2014 best2015 best2016 best2017 breakcore breaks cyberpunk dark ambient downtempo dreampop drone drum&bass dub dubstep dubtechno electro electronic experimental female vocal future garage glitch hip hop idm indie indietronica industrial jazzy krautrock live modern classical noir oldschool post-rock shoegaze space techno tribal trip hop Latest The best in 2017 - albums, places 1-33 12/30/2017 The best in 2017 - albums, places 66-34 12/28/2017 The best in 2017. -

Easter Eggs: Hidden Tracks and Messages in Musical Mediums

Proceedings ICMC|SMC|2014 14-20 September 2014, Athens, Greece Easter Eggs: Hidden Tracks and Messages in Musical Mediums Jonathan Weinel, Darryl Griffiths and Stuart Cunningham Creative & Applied Research for the Digital Society (CARDS) Glyndŵr University Plas Coch Campus, Mold Road, Wrexham, LL11 2AW, Wales +44 1978 293070 {j.weinel | Griffiths.d | s.cunningham}@glyndwr.ac.uk ABSTRACT the programmers’ office, in the style of the video game Doom [2]. The hidden game features credits and digital ‘Easter eggs’ are hidden components that can be found in images of the programmers. It is accessed by carrying computer software and various other media including out a particular series of actions on the 95th row of a music. In this paper the concept is explained, and various blank spreadsheet upon opening Excel. examples are discussed from a variety of mediums in- cluding analogue and digital audio formats. Through this discussion, the purpose of including easter eggs in musi- cal mediums is considered. We propose that easter eggs can serve to provide comic amusement within a work, but can also serve to support the artistic message of the art- work. Concealing easter eggs in music is partly depend- ent on the properties of the chosen medium; vinyl records Figure 1. Screenshots from the ‘hall of tortured souls’, in Mi- may use techniques such as double grooves, while digital crosoft Excel 95. formats such as CD may feature hidden tracks that follow long periods of empty space. Approaches such as these This paper will consider the purpose and realisation of and others are discussed. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Linda Martell, A.K.A

The Clerk’s Black History Series Debra DeBerry Clerk of Superior Court DeKalb County Linda(June 4, Martell 1941 -) Linda Martell, a.k.a. Thelma Bynem, was born June 4, 1941 in Leesville, South Carolina. One of five children, she began singing at the age of five and learned to cook for her family by the age of seven. She sang with a gospel church group with three of her bothers and later formed a trio called The Anglos with one of her sisters and a cousin; they performed at local clubs in the late 1950’s. She married in 1960 and the couple had three children. She changed her name at the suggestion of a local DJ who said she needed a better stage name. The DJ suggested she looked like a “Linda” - and Linda Martell and the Anglos were born. They released their first single in 1962, “A Little Tear (Was Falling From My Eyes)” on the Fire record label based in New York. Unfortunately, the single was never promoted and didn’t sell. They also recorded two more singles with no real financial return for their effort. Around 1966, Linda and her husband attended an Otis Redding concert in South Carolina. At one point during the evening, Otis, who had been paying particular attention to Linda, shocked the crowd (and her husband) by kissing Linda during the performance. Otis later asked Linda to go on the road with him, but her husband opined against it, fearing he would lose his wife to the popular singer. As fate would have it, Otis Redding died one year later in a plane crash while traveling on tour. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

Variations #6

Curatorial > VARIATIONS VARIATIONS #6 With this section, RWM continues a line of programmes devoted to exploring the complex map of sound art from The Library different points of view organised in curatorial series. We encounter the establishment of sound libraries, collections explicitly curated 'Variation' is the formal term for a musical composition based for further use: sound objects presented as authorless, unfinished ingredients. on a previous musical work, and many of those traditional Though some libraries contain newly commissioned generic sounds, specifically methods (changing the key, meter, rhythm, harmonies or designed for maximum flexibility, the most widely used sounds are often sourced tempi of a piece) are used in much the same manner today from commercial recordings, freed from their original context to propagate across by sampling musicians. But the practice of sampling is more dozens to hundreds of songs. From presets for digital samplers to data CD-ROMs than a simple modernization or expansion of the number of to hip-hop battle records, sounds increasingly detach from their sources, used options available to those who seek their inspiration in the less as references to any original moment, and more as objects in a continuous refinement of previous composition. The history of this music public domain. traces nearly as far back as the advent of recording, and its As hip-hop undergoes a conservative retrenchment in the wake of the early emergence and development mirrors the increasingly self- nineties sampling lawsuits, a widening variety of composers and groups expand conscious relationship of society to its experience of music. the practice of appropriative audio collage as a formal discipline. -

Thehard DATA Summer 2015 A.D

FFREE.REE. TheHARD DATA Summer 2015 A.D. EEDCDC LLASAS VEGASVEGAS BASSCONBASSCON & AAMERICANMERICAN GGABBERFESTABBERFEST REPORTSREPORTS NNOIZEOIZE SUPPRESSORSUPPRESSOR INTERVIEWINTERVIEW TTHEHE VISUALVISUAL ARTART OFOF TRAUMA!TRAUMA! DDARKMATTERARKMATTER 1414 YEARYEAR BASHBASH hhttp://theharddata.comttp://theharddata.com HARDSTYLE & HARDCORE TRACK REVIEWS, EVENT CALENDAR1 & MORE! EDITORIAL Contents Tales of Distro... page 3 Last issue’s feature on Los Angeles Hardcore American Gabberfest 2015 Report... page 4 stirred a lot of feelings, good and bad. Th ere were several reasons for hardcore’s comatose period Basscon Wasteland Report...page 5 which were out of the scene’s control. But two DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 factors stood out to me that were in its control, Noize Suppressor Interview... page 8 “elitism” and “moshing.” Th e Visual Art of Trauma... page 9 Some hardcore afi cionados in the 1990’s Q&A w/ CIK, CAP, YOKE1... page 10 would denounce things as “not hardcore enough,” Darkmatter 14 Years... page 12 “soft ,” etc. Th is sort of elitism was 100% anti- thetical to the rave idea that generated hardcore. Event Calendar... page 15 Hardcore and its sub-genres were born from the PHOTO CREDITS rave. Hardcore was made by combining several Cover, pages 5,8,11,12: Joel Bevacqua music scenes and genres. Unfortunately, a few Pages 4, 14, 15: Austin Jimenez hardcore heads forgot (or didn’t know) they came Page 9: Sid Zuber from a tradition of acceptance and unity. Granted, other scenes disrespected hardcore, but two The THD DISTRO TEAM wrongs don’t make a right. It messes up the scene Distro Co-ordinator: D.Bene for everyone and creativity and fun are the fi rst Arcid - Archon - Brandon Adams - Cap - Colby X. -

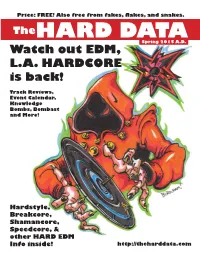

Thehard DATA Spring 2015 A.D

Price: FREE! Also free from fakes, fl akes, and snakes. TheHARD DATA Spring 2015 A.D. Watch out EDM, L.A. HARDCORE is back! Track Reviews, Event Calendar, Knowledge Bombs, Bombast and More! Hardstyle, Breakcore, Shamancore, Speedcore, & other HARD EDM Info inside! http://theharddata.com EDITORIAL Contents Editorial...page 2 Welcome to the fi rst issue of Th e Hard Data! Why did we decided to print something Watch Out EDM, this day and age? Well… because it’s hard! You can hold it in your freaking hand for kick drum’s L.A. Hardcore is Back!... page 4 sake! Th ere’s just something about a ‘zine that I always liked, and always will. It captures a point DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 in time. Th is little ‘zine you hold in your hands is a map to our future, and one day will be a record Photo Credits... page 14 of our past. Also, it calls attention to an important question of our age: Should we adapt to tech- Event Calendar... page 15 nology or should technology adapt to us? Here, we’re using technology to achieve a fun little THD Distributors... page 15 ‘zine you can fold back the page, kick back and chill with. Th e Hard Data Volume 1, issue 1 For a myriad of reasons, periodicals about Publisher, Editor, Layout: Joel Bevacqua hardcore techno have been sporadic at best, a.ka. DJ Deadly Buda despite their success (go fi gure that!) Th is has led Copy Editing: Colby X. Newton to a real dearth of info for fans and the loss of a Writers: Joel Bevacqua, Colby X. -

World and Time

z World and Time A Short Trip Around The Musical Globe z Jamaica . Reggae is a musical genre originating from Jamaica, through the expansion of two existing styles, Ska and Rocksteady. It has associations with the Rastafarian religious movement . Lyrics are often delivered in differing forms of Jamaican English (local dialect known as ‘patois’), with subjects based around the Rastafarian movement, social injustice, racism, peace and love. It is characterised by melodies played on the bass guitar, rhythmic stabs (known as ‘skank’) played on guitar/keyboards, and three drum grooves that feature syncopation, which means accenting weak beats of the bar – the one drop, rockers and steppers. The ‘One Drop’ groove z . Listen to the song ‘Get Up Stand Up’ by Bob Marley, the most famous exponent of the Reggae genre: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tg97JiBn1kE . Here is a sample of the drum groove in notation . Below is the groove isolated for you to play – Look at the notation and listen to the groove – notice how the bass drum is missing from the start of beats 1 and 3, which is uncommon in most other pop music genres. Try to count along – it’s difficult without the bass drum on 1 and 3! Cubaz . Afro-Cuban music is comprised of a number of styles, including montuno, cha cha cha and mambo. These styles gave birth to a huge sub-genre of Latin music known as Salsa. This was pioneered by Cuban musicians who had migrated to New York City in USA. Salsa lyrics can range from romantic affairs of the heart, to political subject matter (based around communism). -

Westminsterresearch Synth Sonics As

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Synth Sonics as Stylistic Signifiers in Sample-Based Hip-Hop: Synthetic Aesthetics from ‘Old-Skool’ to Trap Exarchos, M. This is an electronic version of a paper presented at the 2nd Annual Synthposium, Melbourne, Australia, 14 November 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 2nd Annual Synthposium Synthesisers: Meaning though Sonics Synth Sonics as Stylistic Signifiers in Sample-Based Hip-Hop: Synthetic Aesthetics from ‘Old-School’ to Trap Michail Exarchos (a.k.a. Stereo Mike), London College of Music, University of West London Intro-thesis The literature on synthesisers ranges from textbooks on usage and historiogra- phy1 to scholarly analysis of their technological development under musicological and sociotechnical perspectives2. Most of these approaches, in one form or another, ac- knowledge the impact of synthesisers on musical culture, either by celebrating their role in powering avant-garde eras of sonic experimentation and composition, or by mapping the relationship between manufacturing trends and stylistic divergences in popular mu- sic. The availability of affordable, portable and approachable synthesiser designs has been highlighted as a catalyst for their crossover from academic to popular spheres, while a number of authors have dealt with the transition from analogue to digital tech- nologies and their effect on the stylisation of performance and production approaches3. -

![(RECORDING BEGINS) That's a Guy from Embargo [Frankfurt]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0290/recording-begins-thats-a-guy-from-embargo-frankfurt-1140290.webp)

(RECORDING BEGINS) That's a Guy from Embargo [Frankfurt]

GHETTOBLASTER 1997|12|09 23|23 Page 5 YOU GUYS DON’T TALK TO PEOPLE AT PARTIES EITHER. WHY’S THAT? you don't have to talk to them, you know, because everything is changing. the good, they stay, and you know them after a while. you don't have to talk to every shithead out there. this is not arrogant but its just easier for life, you know. you don't have to have so much shit in your head. WHERE DO YOU GET REACTIONS TO YOUR MUSIC FROM? oh, from nearly all over the world, especially Australia: they are totally into our hardcore stuff. Italy and Paris, France, the market there is very good. Austria, Switzerland, England...nearly all over Europe. in America, it's a little bit hard to get our records there. i think they don't leave New York so i think many people know us there but we don't get many reactions from America. WHO DOES YOUR ARTWORK? (RECORDING BEGINS) that's a guy from Embargo [Frankfurt]. he has a merchandise store, a mailorder service, a distribution for an exclusive This conversation was apprehended from official source recordings from February 1995. The voice has been positively collection of clubwear and merchandise/rave stuff etc... he's doing our artwork for the records and PCP merchandise. linked to a “Torsten Lambert”; a relation of the Acardipane collective. At the time of this recording, PCP’s massive out- WHAT DO YOU CALL YOUR MUSIC? put and influence on the world’s darker imaginations was just beginning to painfully trail off.