My Persian Carpet: a Family and Cultural Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson: Two Carpets Essential Questions

Lesson: Two Carpets Essential Questions: Why are carpets important in Islamic cultures? What are the basic characteristics of West Asian carpet design? What are the similarities and differences between the Ottoman Turkish and Iranian carpets discussed in this lesson? Learning experience: Students will become familiar with two roughly contemporaneous carpets, one from Ottoman Anatolia and one from Iran. They will analyze their design and learn about some of the aesthetic priorities of the people who created them. Anticipatory set: In your house, your apartment, or your room: what kind of objects do you surround yourself with? Which are useful? Which are decorative? Which are both? Context: Carpets have been made for thousands of years throughout Central and West Asia. Flat-woven textiles (kilims—carpets without pile) were made in Turkey at least as early as 7000 BCE. The oldest surviving woolen pile carpet dates from the fifth century BCE, found in a burial site in the Altai mountains of southern Siberia. For pastoral nomadic inhabitants of the Eurasian steppe, carpets served as “floor coverings, prayer mats, tent decorations, canopies, as symbols of power, privilege and riches” (Abas 2004: 11). In the sedentary world of cities, towns, and farming villages, carpets were also more than floor covering. They were "an integral part of one’s living arrangements, one which took the place of chairs, beds, and sometimes tables” (www: Erdmann). Carpets, in short were necessities, not merely decorations, and so were worth the great care that was lavished on them. Those belonging to the wealthy never remained in one place all the time. -

Persian Collections

Size: 1 (Ft) = 30cm • SELL • TRADE PERSIAN • WASH MASTER PIECE MASTER PIECE • RESTORE NEW AND ANTIQUE 489594-P CARPETS www.persiancollections.com Collections THE fine persian carpet gallery Open 7 Days A Week Desa Sri Hartamas 32-2 & 34-2, Jalan 25/70A 6. Super Fine Tabriz, signed by Master Weaver. 11. Showroom 12. Great Stock. BIGGEST CARPET Kurk wool & silk on silk base, 400 x 600 cm. Take 8 years to weave. MUST SEE!!! Desa Sri Hartamas 50480 Kuala Lumpur SALE ☎ 03-2300 6966 Bangsar Shopping Centre 50% - 75% F4A, 1st Floor (East Wing) Bangsar Shopping Centre off 59000 Kuala Lumpur ☎ 03-2094 6966 Holiday Villa - Jln Ampang BGM-12, Ground Floor Megan Embassy (Holiday Villa) Jln Ampang, K.L. ☎ 012-308 0068 5. Super Fine Qum Silk, signed by Master Weaver. 7. Large selection on extra large carpet. 6th June 20th July 2008 13. Great Turnover! New Stock Arrive Monthly. 14. See Our Extensive Stock Selection. SALE Silk on silk base, 250 x 350 cm. Take more than 8 years to weave. MUST SEE!!! BRINGING WONDERS OF PERSIA TO YOUR HOME MORE THAN 5,000 CHOICE OF PERSIAN CARPETS ON SALE MASTER PIECE COLLECTABLE ITEM 1. Tribal Kilim Stool. 2. Fine Persian Tabriz. Dining Room Size. 8. Super Fine Qum Silk, sign by Master Weaver. 15. Super Fine Nain. 16. Super Fine Tabriz. Silk on silk base, 350 x 500 cm. Take 10-12 years to weave. DO NOT MISS!!! Wool & silk on cotton base, 500 x 800 cm Wool & silk on cotton base, 300 x 400 cm BEST BUY RM ***** MASTER PIECE 3. -

Glossary of Carpet and Rug Terms

Glossary of Carpet and Rug Terms 100% Transfer - The full coverage of the carpet floor adhesive into the carpet backing, including the recesses of the carpet back, while maintaining full coverage of the floor. Absorbent Pad (or Bonnet) Cleaning - A cleaning process using a minimal amount of water, where detergent solutions are sprayed onto either vacuumed carpet, or a cotton pad, and a rotary cleaning machine is used to buff the carpet, and the soil is transferred from the carpet to the buff pad, which is changed or cleaned as it becomes soiled. Acrylic/Modacrylic - A synthetic fiber introduced in the late 1940's, and carpet in the late 1950's, it disappeared from the market in the late 1980's due to the superior performance of other synthetics. Acrylics were reintroduced in 1990 in Berber styling to take advantage of their wool-like appearance. Modacrylic is a modified acrylic. While used alone in bath or scatter rugs, in carpeting it's usually blended with an acrylic. Acrylics are known for their dyeability, wearability, resistance to staining, color retention and resistance to abrasion. They're non-allergenic, mildew proof and moth proof. Adhesive - A substance that dries to a film capable of holding materials together by surface attachment. Anchor Coat - A latex or adhesive coating applied to the back of tufted carpet, to lock the tufts and prevent them from being pulled out under normal circumstances. Antimicrobial - A chemical treatment added to carpet to reduce the growth of common bacteria, fungi, yeast, mold and mildew. Antistatic - A carpet's ability to dissipate an electrostatic charge before it reaches a level that a person can feel. -

Treasures from Near Eastern Looms

The Bowdoin College Library Treasures from Near Eastern Looms ERNEST H. ROBERTS BRUNSWICK, MAINE 1981 Bowdoin College Museum of Art Brunswick, Maine September 11, 1981 to November 22, 1981 The Textile Museum Washington, District of Columbia December 11, 1981 to February 6, 1982 Cover: Carpel Fnn>incni, Caucasian, Dagistan area, ca. 1850 Photographs by Robert H. Stillwell Design by Michael W. Mahan Printed byJ.S. McCarthy Co., Inc., Augusta, Maine Copyright © 1981 by Ernest H. Roberts Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 81-68474 ISBN: 0-916606-02-3 Portions of this catalogue are reprinted in altered form from other publications. We are indebted to the following institutions for per- mission to use their material: to the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio, for the chapter introductions and descriptions of plates 12, 19, 24, 28, 63, and 65, which appeared in "Catalogue of Islamic Carpets," Allen An Museum Bulletin 3 (1978-1979) by Ernest H. Roberts; to The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C., for glossary entries and drawings from "Definitions and Explana- tions," a section of Early Caucasian Ru^s by Charles Grant Ellis, published by that museum in 1975, and for the loan of the map which appears on page 61 of this book; to the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, for descriptions of plates 28, 35, 44, 57, and 67 from A Rich Inheritance: Oriental Ruj^s oj 19th and Early 20th Centuries, published by that museum in 1974; and to the Near Eastern Art Research Center, Inc., for the description of plate 68 from Islamic Carpets by Joseph V. -

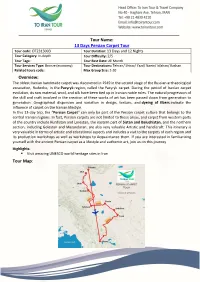

13 Days Persian Carpet Tour Overview

Tour Name: 13 Days Persian Carpet Tour Tour code: OT2313003 Tour Duration: 13 Days and 12 Nights Tour Category: In-depth Tour Difficulty: 2/5 Tour Tags: Tour Best Date: All Month Tour Services Type: Bronze (economy) Tour Destinations: Tehran/ Shiraz/ Yazd/ Naein/ Isfahan/ Kashan Related tours code: Max Group Size: 2-20 Overview: The oldest Iranian handmade carpet was discovered in 1949 in the second stage of the Russian archaeological excavation, Rudenko, in the Pazyryk region, called the Pazyryk carpet. During the period of Iranian carpet evolution, its raw material, wool, and silk have been tied up in Iranian noble roles. The natural progression of the skill and craft involved in the creation of these works of art has been passed down from generation to generation. Geographical dispersion and variation in design, texture, and dyeing of fibers indicate the influence of carpet on the Iranian lifestyle. In this 13-day trip, the “Persian Carpet” can only be part of the Persian carpet culture that belongs to the central Iranian regions. In fact, Persian carpets are not limited to these areas, and carpet from western parts of the country include Kurdistan and Lorestan, the eastern part of Sistan and Baluchistan, and the northern section, including Golestan and Mazandaran, are also very valuable Artistic and handicraft. This itinerary is very valuable in terms of artistic and educational aspects and includes a visit to the carpets of each region and its production workshops as well as workshops to Acquaintance them. If you are interested in familiarizing yourself with the ancient Persian carpet as a lifestyle and authentic art, join us on this journey. -

Azerbaijani Carpet of Safavid Era

Traditional crafts Roya TAGIYEVA Doctor of Arts Azerbaijani carpet of Safavid era Fragments of the Sheikh Safi carpet. Tabriz, 1539. Victoria and Albert Museum, London he Azerbaijani carpet has always, especially during mastered the art of miniature painting. In this respect, the cultural upsurge in the East, been a synthe- the 16th century, which went down in the history of Azer- Tsis of many aesthetic principles. Remaining tra- baijan as a golden age of culture, is characteristic. The ditional in their spirit and organization of the material, authentic masterpieces of carpet making of that time carpets absorbed a variety of elements of the reality - combined the subtlety and grace of miniature painting, their creators drew motifs from literature and creatively the traditional decorative-planar solution of motifs and 18 www.irs-az.com 2(30), SPRING 2017 Sheikh Safi carpet. Tabriz, 1539. Victoria and Albert Museum, London www.irs-az.com 19 Traditional crafts Namazlig. Tabriz, 16th century. Topkapi Museum, Istanbul 20 www.irs-az.com 2(30), SPRING 2017 Namazlig. Tabriz, 16th century. Topkapi Museum, Istanbul a magnificent color palette reflecting all the colorfulness and diversity of nature. In the 16th century, the Azerbaijani Safavid dynasty, which created a strong centralized state, encouraged the development of culture and art. In Tabriz, the capital of the mighty Safavid state, which became one of the leading cultural centers of the East, a bright and distinc- tive school of miniature painting took shape. Miniatures of this period stored in private collections, in the British Museum in London and in the Topkapi Museum in Istan- bul depict beautiful carpets with Kufic inscriptions, art compositions “islimi”, “khatai”, “bulud”, namaz (prayer) rugs with a smooth background, afshan compositions, “lachak- turunj” compositions, etc., as well as carpets with a plot. -

Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets Carol Bier, the Textile Museum

Graduate Theological Union From the SelectedWorks of Carol Bier February, 1996 Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets Carol Bier, The Textile Museum Available at: https://works.bepress.com/carol_bier/49/ 1 IU1 THE TEXTILE MUSEUM Approaches to Understanding Oriental Carpets CAROL BIER Curator, Eastern Hemisphere Collections The Textile Museum Studio photography by Franko Khoury MAJOR RUG-PRODUCING REGIONS OF THE WORLD Rugs from these regions share stylistic and technical features that enable us to identify major regional groupings as shown. Major Regional Groupings BSpanish (l5th century) ..Egypto-Syrian (l5th century) ItttmTurkish _Indian Persian Central Asian :mumm Chinese ~Caucasian 22 Major rug-producing regions of the world. Map drawn by Ed Zielinski ORIENTAL CARPETS reached a peak in production language, one simply weaves a carpet. in the late nineteenth century, when a boom in market Wool i.s the material of choice for carpets woven demand in Europe and America encouraged increased among pastoral peoples. Deriving from the fleece of a *24 production in Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus.* Areas sheep, it is a readily available and renewable resource. east of the Mediterranean Sea at that time were Besides fleece, sheep are raised and tended in order to referred to as. the Orient (in contrast to the Occident, produce dairy products, meat, lard and hide. The body which referred to Europe). To study the origins of these hair of the sheep yields the fleece. I t is clipped annually carpets and their ancestral heritage is to embark on a or semi-annually; the wool is prepared in several steps journey to Central Asia and the Middle East, to regions that include washing, grading, carding, spinning and of low rainfall and many sheep, to inhospitable lands dyeing. -

CARPET WARRANTY BROCHURE Technical and Cleaning Instructions

CARPET WARRANTY BROCHURE Technical and Cleaning Instructions Please check your sample to confirm what warranties apply Southwind Carpet Mills is proud to provide products made here in the USA. Page 1 of 14 Southwind Warranty Brochure CMGH01162019 HOUSEHOLD TEXTURE SOIL ABRASIVE LIMITED FADE ANTI MANUFACTURING SOUTHWIND LIMITED WARRANTY CHART* COVERAGE** PET RETENTION RESISTANCE WEAR STAIN RESISTANCE STATIC DEFECTS TM So Soft PET 25 Year 25 Year Life Time 25 Year Material Life Time 25 Year Life Time 2 years Sosoft NYLON® 25 Year 25 Year Lift Time 25 Year Material Life Time 25 Year Life Time 2 years NA 20 Year 20 Year 20 Year Material 20 Year NA NA 2 years Office I Solutions™ NA NA NA 10 Year Material NA* NA NA 2 years Polyester / Olefin / Polypropylene SOUTHWIND NA NA 3 Year 3 Year Material 3 Year 3 Year NA 3 years Indoor Outdoor / Carpet * This chart provides a snap shot of the warranties. For full details please refer to the actual copy of your warranty ** Material is pro-rated. For full details please refer to the actual copy of your warranty Page 2 of 14 Southwind Warranty Brochure CMGH01162019 Table of Contents Southwind Warranty Chart 2 General Warranty Information 4 Southwind Carpet Mills Performance Warranty Detail 5 Limited Stain Resistance Warranty 5 Limited Soil Resistance Warranty 6 Limited Anti-Static Warranty 6 Limited Abrasive Wear Warranty 6 Limited Texture Retention Warranty 7 Limited Fade Resistance Warranty 7 Limited Pet Urine Stain Warranty 7 General Terms, Limitations and Warranty Exclusions 8 Proration of Warranties 9 Limitations for all Southwind Carpet Mills' Carpet 10 Southwind Carpet Mills Limited Liability 11 Disclaimer of Implied Warranties 11 Carpet Cushion requirements 11 Homeowners Responsibilities and Obligations 12 How Do I File A Claim? 12 Caring for Your Carpet 12 What Is Normal and Acceptable? What Is Not? 13 Manufacturing Defect Warranty 14 Page 3 of 14 Southwind Warranty Brochure CMGH01162019 This brochure will explain Southwind’s warranty coverage and what you can expect from your recently installed carpet. -

Anatomy of Persian & Oriental

dÌ¿z»ZÀ¼ÁdÌ¿¹Â¸ »Öf{Ä],§d§Z]ÁxËZe0 ½ZÌ¿YËYįdY¾ËYº¸»|« |ÁĬÀ»¹Y|¯Y§d§Z]į «YÁ{ |¿YÃ{¯Á/Y§d§Z]į|Àf/ÅÖ»Y«Y¾Ì·ÁYĸ¼mY YÌ]{ÁZf/{Ö§Z]§»Y{,Á»Y½ZÌ¿YËY{§Ä]vÀ»/v^e dYÄÀÌ»¾ËY{Ä]neÁÔeµZ www.Rug.VestaNar.com Nasir al-Mulk Nasir al-Mulk is a famous historic mosque in the center of Shiraz, located near the Shah Cheragh shrine. It was constructed in the Qajar Dynasty in 1876 by Lord Mirza Hasan Ali Nasir al Mulk. The mosque is known for its extensive use in colored glass in its façade. The construction of the mosque uses other traditional structural elements as well such as “panj kasehi” (five concaves). These days, the mosque is more of a tourist attraction than a place for prayer. Like all mosques in Iran, you must remove your shoes before entering and the floor is lined with Persian rugs from wall to wall. We found out that underneath the rugs is actually a beautiful marble floor as well. www.Rug.VestaNar.com ½YËY¥Z^f{§½Z³|ÀÀ¯{ZÁ½Z³|ÀÀ¯|Ì·ÂeÄË{ZveYÄ»Z¿¶§ ¿Yc¸y{ ¹ÔY¾Ì^»¾Ë{½YÁY§ÄmÂeÄ]¶^«Ä·Z¬»{ÁÄË¿Y¾ÌÌaÃZ¼{ ºË{¯ÃZYZÆ¿Z¿YÖËZÌ¿{¶ËZ»Ä] ½M«cZËMYÖy]ÄÀËY¾¼ dY]Y]ºË¯½M«{cyMÁZÌ¿{cZ¼¸¯Y°e{Y| eį|Äf¨³ Á ºË{ÁMµZj»|ÅZ½YÂÀÄ]dYÄf§³Y«|̯Pe{»cyMÄ]ÄmÂeZÀ¯{ZÌ¿{Ä]ÄmÂeZÆ¿M{įYºË¯ įd¨³ºÌÅYÂy\¸»Ä»Y{Y{®ÀËY Ã|Á|À¿Z» dYÃ{Y{½ZÅZÀ³ÁÖZ »YÕZÌ]]cyMºÅZÌ¿{ºÅÕÁyYÁÕÂÌ¿{[Y~Ã|ÁºË¯½M«{|¿ÁY|y |ÀÀ¯Ö»\ËzeY|mZ»Ä¯Ö¿Z¯Á{ÂÖ»|mZ»{¹{»ÂuY¿Z»Ä¯Ö¯]cyMÁZÌ¿{{[Y~ ì]ÃÂÄËM 3 4 3 3 Ê5§º7 Æ4 3·Á3 É1 7 yZ5 Ì3 7¿|·YÊG 5§º7 Æ4 3·¾Ì3 ¨5 5WZy3 ÓF 5SZÅÂ3 ¸4 y4 |7 3˽7 Oº7 Æ4 3·½Z3 ¯Z3 »3 ®3 X5 3·ÁOZÆ3 5]Y3 yÊ3 5§Ö 3 3 Á3 Ä4 ¼4 YZ7 ÆÌ3 5§3 ¯3 ~7 4˽7 O5×YF |3 mZ5 3 »3 3 À3 »3 ¾7 ¼F »5 º4 3¸7 O¾7 »3 Á3 ºÌ1 -

Afghan Wars, Oriental Carpets, and Globalization

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Anthropology Papers Department of Anthropology 3-2011 Afghan Wars, Oriental Carpets, and Globalization Brian Spooner University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Spooner, B. (2011). Afghan Wars, Oriental Carpets, and Globalization. Expedition, 53 (1), 11-20. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/63 View this article on the Expedition Magazine website. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/63 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Afghan Wars, Oriental Carpets, and Globalization Abstract The afghan war rugs on exhibit at the Penn Museum from April 30 to July 31, 2011, raise a number of interesting questions—about carpets, Afghanistan, and the way the world as a whole is changing. These rugs, which come in a variety of sizes and qualities, derive from a tradition of oriental carpet-weaving that began to attract the attention of Western rug collectors in the late 19th century. Unlike the classic museum pieces that were produced on vertical looms in the cities of western Asia for use in palaces and grand houses, war rugs came from horizontal looms in small tribal communities of Turkmen and Baloch in the areas of central Asia on either side of the northern border of Afghanistan—tribal communities that were incorporated into the Russian Empire in the 19th century. Disciplines Anthropology | Social and Behavioral Sciences Comments View this article on the Expedition Magazine website. This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/63 Afghan Wars, Oriental Carpets, and Globalization by brian spooner he afghan war rugs on exhibit at the Penn Museum from April 30 to July 31, 2011, raise a number of interest- ing questions—about carpets, TAfghanistan, and the way the world as a whole is changing. -

Year Old Historical Background of The

Indian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Life Sciences ISSN: 2231– 6345 (Online) An Open Access, Online International Journal Available at www.cibtech.org/sp.ed/jls/2015/01/jls.htm 2015 Vol.5 (S1), pp. 1838-1856/Sara and Fatemeh Research Article THE ORIGIN OF THE MOTIFS AND THE FOUR- THOUSAND- YEAR OLD HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE PERSIAN CARPET Sara Naeemi Hir and Fatemeh Dehghany Department of Art Research, College of Art and Architecture, Yazd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Yazd, Iran *Author for Correspondence ABSTRACT Carpet is the mirrors of the Islamic and Iranian art and civilization. It is a priceless heritage remaining from a long time ago and has been approved in the birth certificate of our nation. The motifs are amongst the most important and most effective component used in the rug which have a fundamental role in it and attract any viewer at first glance. Rugs and the patterns of rugs have undergone changes in different eras. The data collection method in this article includes using the library resources the research method was historical- descriptive. As each government came to rule throughout history, it brought along change and upheaval with it and has led to change in social and cultural fields of that society. The rugs and the art of rug weaving are also inseparable parts of Iran’s culture which have also undergone this upheaval. Therefore this article has tried to examine the role of the governments in forming rug motifs and the progressing process of this art from the ancient times, the primary periods of Islam and after that up to the present era. -

Areathe Offical Publication of the Oriental Rug Importers Association, Inc

AREATHE OFFICAL PUBLICATION OF THE ORIENTAL RUG IMPORTERS ASSOCIATION, INC. DESIGN FOCUS Brian Murphy SPRING 2016 spring 2016 final.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 3/9/16 11:24 AM Page 2 HERMITAGE COLLECTION TRULY ORIGINAL RUGS, PILLOWS AND THROWS Visit us at High Point | April 16-20, IHFC D320 LOLOIRUGS.CO M/HERMITAGE spring 2016 final.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 3/9/16 11:24 AM Page 2 jamison 53304 jamison 53308 maddox 56503 Invite your customers to experience island-inspired living at its fi nest through the refi ned yet casual Tommy Bahama area rug collection. OWRUGS.COM/ Tommy spring 2016 final.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 3/9/16 11:24 AM Page 2 INTRODUCING THE CHELSEA COLLECTION AN EXCLUSIVE FINE WOOL AND SILK CARPET PRODUCTION N e w J e r s e y D e l h i S h a n g h a i D u b a i M e l b o u r n e spring 2016 final.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 3/9/16 11:24 AM Page 2 spring 2016 final.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 3/16/16 11:57 AM Page 6 From the President’s Desk Dear Colleagues and Friends, will enhance the image of the oriental and orien- tal style rug and spark a new awareness and Judging from reports, the most recent January appreciation of a wide variety of rugs from all rug trade shows were well attended and sales were producing countries. So while congratulations are solid. Dealers in attendance reported they had a in order for members who had been and now will good 2015, finishing the year with be actively importing rugs from strong sales.