Red Diamond Threats Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria Update: August 30-September 4, 2014

Syria Update: August 30-September 4, 2014 6 August 31: Rebels from the 1 August 31 - September 4: After shooting down an Iranian drone on Islamic Front, Kurdish Front, August 31, Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) declared the Israeli border with Jabhat al-Nusra, and other groups Quneitra a “closed military zone” and deployed armored vehicles to the area clashed with ISIS ghters near on September 2. On September 4, IDF struck the regime’s 90th Brigade the Shahba Dam in northern Headquarters in Quneitra after mortars landed in Israeli territory in the Aleppo province, amid ongoing Golan Heights. ree regime soldiers were reported killed. rebel shelling of ISIS positions. 6 Aleppo 2 August 30: ISIS created a social media account for Hasakah “Wilayat al-Furat,” which extends from Abu Kamal in eastern 7 September 2-3: JN and Idlib-based rebels seized Syria to al-Qaim in western Iraq. is is the rst time ISIS Idlib four military checkpoints just northwest of Hama city, has announced a cross-border “Wilayat” – a term they use for 10 ar-Raqqa near Halfaya and Maharda. e checkpoints lie near a the administrative units of their areas of governance. regime supply route leading to the al-Ghab Plain and Latakia Idlib Province. 3 September 4: Rebel groups including Jabhat al-Nusra ( JN), al-Muthanna Islamic Movement, and FSA aliated 7 8 September 2: e Islamic Front and other rebels have Hama continued to target the Hama Military Airport, a major groups announced a new oensive in Quneitra province and Deir ez-Zour seized the villages of Majduliya and Masharah, located 8 Hama Military Airport regime transportation and resupply hub, and claimed to southeast of Quneitra city. -

Boko Haram, Iran, and Syria

SEPT 2016 Vol 2 Thr eat Tactics Report Thr eat Tactics Report Compendium Compendium BBookk oo HHaarraamm,, IIrraann,, aanndd SSyyrriiaa Includes a sampling of Threat Action Reports and Red Diamond articles TRADOC G-2 ACE Threats Integration DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Threat Tactics Report Compendium, Vol 2 Introduction TRADOC G-2 ACE Threats Integration (ACE-TI) is the source of the Threat Tactics Report (TTR) series of products. TTRs serve to explain to the Army training community how an actor fights. Elements that contribute to this understanding may include an actor’s doctrine, force structure, weapons and equipment, education, and warfighting functions. An explanation of an actor’s tactics and techniques is provided in detail along with recent examples of tactical actions, if they exist. An actor may be regular or irregular, and a TTR will have a discussion of what a particular actor’s capabilities mean to the US and its allies. An important element of any TTR is the comparison of the real-world tactics to threat doctrinal concepts and terminology. A TTR will also identify where the conditions specific to the actor are present in the Decisive Action Training Environment (DATE) and other training materials so that these conditions can easily be implemented across all training venues. Volume 2: Boko Haram, Iran, and Syria This compendium of Threat Tactics Reports, Volume 2, features the most current versions of three TTRs: Boko Haram (Version 1.0, published October 2015); Iran (Version 1.0, published June 2016); and Syria (Version 1.0, published February 2016). -

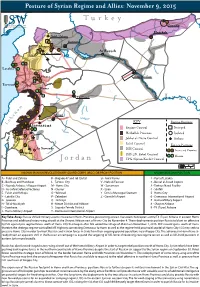

Regime and Allies: November 9, 2015

Posture of Syrian Regime and Allies: November 9, 2015 Turkey Z Qamishli Hasakah Nubl / Zahraa A Kuweires Aleppo B E C D Ar Raqqah Fu’ah / Kefraya Idlib 4 1 F G Latakia 2 H I J Hama Deir ez-Zor 3 7 K Tartous L Homs 5 M S 9 Y R I A N 8 T4 (Tiyas) Iraq n o n O a Sayqal b P e KEY Regime Positions L Q R Damascus S T 6 Regime Control Besieged U V Hezbollah Presence Isolated W Quneitra Jabhat al-Nusra Control Airbase l Rebel Control e X Foreign Positions a r As Suwayda ISIS Control s Y A B Iran and Proxies I Deraa ISIS, JN, Rebel Control 1 2 Russia Jordan YPG (Syrian Kurds) Control 10 mi 20 km KNOWN IRANIAN REVOLUTIONARY GUARD CORPS (IRGC) OR PROXY POSITION KNOWN RUSSIAN POSITION A - Nubl and Zahraa K - Brigade 47 and Tel Qartal U - Amal Farms 1 - Port of Latakia B - Bashkuy and Handarat L - Tartous City V - Nabi al-Fawwar 2 - Bassel al-Assad Airport C - Neyrab Airbase / Aleppo Airport M - Homs City W - Sanamayn 3 - Tartous Naval Facility D - As-Sara Defense Factories N - Qusayr X - Izraa 4 - Slinfah E - Fu’ah and Kefraya O - Yabroud Y - Dera’a Municipal Stadium 5 - Homs City F - Latakia City P - Zabadani Z - Qamishli Airport 6 - Damascus International Airport G - Joureen Q - Jamraya 7 - Hama Military Airport H - Tel al-Nasiriyah R - Mezze District and Airbase 8 - Shayrat Airbase I - Qumhana S - Sayyida Zeinab District 9 - T4 (Tiyas) Airbase J - Hama Military Airport T - Damascus International Airport Key Take-Away: Russia shifted military assets into eastern Homs Province, positioning at least ve attack helicopters at the T4 (Tiyas) Airbase in eastern Homs Province and additional rotary-wing aircraft at the Shayrat Airbase east of Homs City by November 4. -

(CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA-021

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA-021 April 2017 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, William Raynolds, Allison Cuneo, Kyra Kaercher, Darren Ashby Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports Syria 9 Incident Reports Iraq 86 Incident Reports Libya 121 Satellite Imagery and Geospatial Analysis 124 Heritage Timeline 127 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● New video footage shows damage to al-Kabir Mosque in al-Bab, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0048 ● New video footage shows damage to al-Iman mosque in al-Bab, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0049 ● New photographs show cleanup and reconstruction efforts taking place at Beit Ghazaleh in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0050 ● New photographs show cleanup and reconstruction efforts taking place at the al-Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0051 ● New photographs show cleanup and reconstruction efforts taking place at Suq Wara al-Jame in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0052 ● Shells land near the National Museum in Damascus, Damascus Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0053 ● Reported SARG airstrikes severely damage al-Sahbat al-Abrar Mosque in Damascus, Damascus Governorate. -

Erkenntnismittelliste Syrien

VERWALTUNGSGERICHT STADE Verzeichnis der vorhandenen Materialien über die Arabische Republik Syrien - 10. Kammer - Stand: 16.09.2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Das Gericht beabsichtigt, gemäß § 86 VwGO die genannten Materialien gegebenenfalls zur Entscheidung heranzuziehen. Falls Sie Einsicht in ein nicht frei verfügbares Erkenntnismit- tel benötigen, wenden Sie sich bitte an die Service-Einheit der 10. Kammer. I. Auswärtiges Amt A. Lageberichte 01.04.2004 13.12.2004 14.07.2005 17.03.2006 26.02.2007 05.05.2008 09.07.2009 28.12.2009 (Ad-hoc Ergänzungsbericht) 07.04.2010 (Ad-hoc Ergänzungsbericht) 27.09.2010 17.02.2012 (Ad-hoc-Bericht) 13.11.2018 Stand: November 2018 kein regulärer Asyllagebericht; Er- stellung im Hinblick auf die IMK im November 2018 20.11.2019 Stand: November 2019 kein regulärer Asyllagebericht; Er- stellung im Hinblick auf die IMK im Dezember 2019 19.05.2020 Fortschreibung des Berichts über die Lage in der Arabischen Republik Sy- rien vom November 2019 (Stand: Mai 2020), kein regulärer Asyllage- bericht; Erstellung im Hinblick auf die IMK im Juni 2020 04.12.2020 Bericht über die Lage in der Arabischen Republik Syrien (Stand: November 2020), kein regulärer Asyllagebericht; Erstellung im Hin- blick auf die IMK im Dezember 2020 - 2 - B. Auskünfte Datum Adressat Inhalt 14.01.2004 VG Darmstadt staatenlose Kurden; rot-orange- nes Plastikdokument; Wehr- dienst 14.01.2004 VG Darmstadt staatenlose Kurden; Ausweispa- piere; Bescheinigung des Orts- vorstehers; rot-orangene Plas- tikkarte; Maktumin 14.01.2004 VG Darmstadt Echtheit Personaldokument - Wehrdienst staatenloser Kurden 19.01.2004 VG Darmstadt Identitätsbescheinigung eines Mukhtars; geringer Beweiswert 19.01.2004 VG Bayreuth Identitätsbescheinigung; Volkszäh- lung 1962; rot-orangene Plastikkar- ten 04.03.2004 VG Braunschweig Ehrenmorde; Familienehre; Az. -

Syria Conflict (RAS) Is Now Produced Quarterly, Replacing 3.7 Deir-Ez-Zor the Monthly RAS of 2013

1. OVERVIEW 1.1 Executive Summary 1.2 Timeline Q3 1.3 Armed conflict and possible developments 1.4 Humanitarian Population Profile 1.5 Displacement profile 1.6 Humanitarian Access 1.7 Possible developments 1.8 Data sources and limitations REGIONAL 2. COUNTRYWIDE SECTORAL ANALYSIS 2.1 Protection 2.2 WASH 2.3 Livelihoods and Food Security 2.4 Shelter NFI ANALYSIS 2.5 Health 2.6 Education 3. GOVERNORATE PROFILES 3.1 Aleppo 3.2 Al-Hasakeh 3.3 Ar-Raqqa 3.4 As-Sweida Q3 2014 | 13 OCTOBER 2014 3.5 Damascus/Rural Damascus 3.6 Dar’a This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) is now produced quarterly, replacing 3.7 Deir-ez-Zor the monthly RAS of 2013. It seeks to bring together information from all sources in 3.8 Lattakia the region and provide holistic analysis of the overall Syria crisis. While Part I focuses on the situation within Syria, Part II covers the impact of the crisis on neighbouring 3.9 Hama countries. More information on how to use this document can be found on page 2. 3.10 Homs Please note that place names which are underlined are hyperlinked to their location 3.11 Idleb on Google Maps. The Syria Needs Analysis Project welcomes all information that could 3.12 Quneitra complement this report. For more information, comments or questions please email 3.13 Tartous [email protected]. 1. OVERVIEW 1.1 Executive Summary 1.2 Possible Developments 1.3 Timeline Q3 1.4 Humanitarian Population Profile 2. COUNTRIES 2.1 Lebanon 2.2 Jordan 2.3 Turkey 2.4 Iraq 2.5 Egypt ANNEX 1. -

DCS Table of Frequencies All Maps V10.Xlsx

DCS Syria Table of Frequencies Airfield Lat (N) Long (E) Runway(s) (ft) UHF / VHF TACAN VOR ILS (Runway/Frequency/Course) Elevation MF/HF ICAO Abu al-Duhur AB 35˚43'53" 37˚07'07" 09-27 (9496') 250.35 / 122.20 - - - 820' 3.950 / 38.80 OS57 Adana Sakirpasa Airport 36˚59'17" 35˚17'28" 05-23 (9071') 250.90 / 121.10 - 112.70 (ADA)RWY 05/108.70/056˚ 55' 4.225/39.350 LTAF Al Qusayr 34˚34'00" 36˚35'07" 10-28 (9600') 251.25 / 119.20 - - - 1729' 4.400 / 39.70 OS70 Al-Dumayr Military Airport 33˚36'16" 36˚44'08" 06-24 (9843') 251.55 / 120.30 - - - 2066' 4.550 / 40.00 OS61 Aleppo Int Airport 36˚10'55" 37˚12'37" 09-27 (9496') 250.75 / 119.10 - 114.50 (ALE) - 1253' 4.150 / 39.20 OSAP An Nasiriyah AB 33˚55'35" 36˚52'31" 04-22 (8318') 251.35 / 122.30 - - - 2746' 4.450 / 39.80 OS64 Bassel Al-Assad Int Airport 35˚24'38" 35˚56'52" 17-35 (9168') 250.45 / 118.10 - 114.80 (LTK) RWY 17/109.10/179˚ 93' 4.000 / 38.90 OSLK Beirut-Rafic Hariri Int 33˚50'14" 35˚29'14" 17-35 (10566'), 251.40 / 118.90 - 112.60 (KAD) RWY 17/109.50/179˚ RWY 16/110.10/169˚ 39' 4.475 / 39.85 OLBA 03-21, 16-34 RWY 03/110.70/035˚ Damascus Int Airport 33˚24'55" 36˚30'15" 05L-23R (11903'), 251.45 / 118.50 - 116.00 (DAM)RWY 23R/109.90/230˚ RWY 05R/111.10/050˚ 2007' 4.500 / 39.90 OSDI 05R-23L Eyn Shemer 32˚26'30" 35˚00'06" 09-27 (3826') 250.00 / 123.40 - - - 93' 3.750 / 38.40 LLES Gaziantep 36˚57'05" 37˚27'52" 10-28 (8871') 250.05 / 121.10 - 116.70 (GAZ)RWY 28/109.10/286˚ 2287' 3.775/38.450 LTAJ H4 35˚32'12" 38˚12'22" 10-28 (7179') 250.10 / 112.60 - - - 2257' 3.800 / 38.50 OJHR Haifa Airport -

An Army in All Corners: Assad's Campaign Strategy

APRIL 2015 CHRISTOPHER KOZAK MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 26 “AN ARMY IN ALL CORNERS” ASSAD’S CAMPAIGN STRATEGY IN SYRIA Cover: February 11, 2015A fighter loyal to Syria’s President Bashar Al-Assad hangs his picture as fellow fighters rest by a Syrian national flag after gaining control of the area in Deir al-Adas, a town south of Damascus, Daraa countryside February 10, 2015. Syrian government troops and their allies in the Lebanese group Hezbollah pressed a major offensive in southern Syria on Wednesday, taking new ground in a campaign against insurgents who pose one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Syrian state TV broadcast live from Deir al-Adas, a town some 30 km (19 miles) south of Damascus that it said had been captured. The sound of artillery being fired could be heard. The nearby town of Deir Maker was also captured, state TV said. Picture taken February 10, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2015 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2015 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org CHRISTOPHER KOZAK MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 26 “AN ARMY IN ALL CORNERS” ASSAD’S CAMPAIGN STRATEGY IN SYRIA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 26 | “AN ARMY IN ALL CORNERS” | CHRISTOPHER KOZAK | APRIL 2015 U.S. -

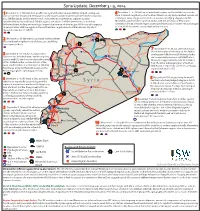

Syria SITREP MAP 2014-12-02

Syria Update: December 3 - 9, 2014 1 December 2 - 9: ISIS launched an oensive against the Deir ez-Zour Military Airport, seizing con- 6 December 3 – 9: ISIS militants clashed with regime and Hezbollah forces in the trol over several villages and checkpoints on the eastern outskirts of the base after clashes involving Hajar al-Aswad neighborhood of southern Damascus city and published a photo set two SVBIED attacks. On December 6 and 7, ISIS militants launched two separate assaults claiming to show a large number of local residents pledging allegiance to ISIS. spearheaded by two additional SVBIEDs against the airport itself but were forced to withdraw Meanwhile, Jaysh al-Islam reported clashes with ISIS amidst over fty regime following heavy shelling and an alleged regime deployment of chlorine gas. ISIS forces also engaged airstrikes in the Bir al-Qaseb region southeast of Damascus. ISIS later released images in heavy clashes with the regime in the southeastern neighborhoods of Deir ez-Zour city which of a small reinforcement convoy deployed to the area. involved a tank-borne SVBIED. Qamishli Ayn al-Arab 3 Ras al-Ayn 2 December 3: JN detonated a car bomb in the northern 2 Masakin Barzeh neighborhood of Damascus city, killing four regime soldiers. 4 Aleppo Hasakah 7 December 3 - 5: JN and other rebel forces seized the regime-held village of Abu Dali in Idlib Sara 3 December 2 – 9: YPG forces advanced in southeastern Idlib Province following clashes ar-Raqqa southern Ayn al-Arab/Kobane amidst ongoing which reportedly involved a JN VBIED attack. -

Transformations of the Syrian Military: the Challenge of Change and Restructuring

Transformations of the Syrian Military: The Challenge of Change and Restructuring Note of Appreciation Omran Center for Strategic Studies expresses its appreciation to the Carnegie Middle East Center for its partnership and support in this project funded by the European Union and Germany as part of the Syria Peace Process Support Initiative (SPPSI). All the information, ideas, opinions, themes and supplements contained in this book are the express the views of the authors and their research efforts and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Carnegie Middle East Center or the donors. -3- -3- Concepts and Practices -4- -4- Transformations of the Syrian Military: The Challenge of Change and Restructuring Omran Center for Strategic Studies -5- Omran Center for Strategic Studies An independent think tank and policy research center focusing on presenting an objective understanding of Syria and the region to become a reference for public policies impacting the region. Omran began in November 2013 in Istanbul, Turkey. It publishes studies and policy briefs regarding Syrian and regional affairs in the areas of politics, economic development, and local administration. Omran also conducts round-table discussions, seminars, and workshops that promote a more systematic and methodical culture of decision making among future leaders of Syria. Omran’s work support decision making mechanisms, provide practical solutions and policy recommendations to decision makers, identify challenges within the Syrian context, and foresee scenarios and alternative solutions Website: www.OmranStudies.org Email: [email protected] Publish date in English: December 31, 2018 © All rights reserved to Omran for Strategic Studies -6- Contributors Navvar Şaban Bashar Narsh, Ph.D Maen Tallaa Col. -

Summary-Of-Consultation-Results.Pdf

1 Contents Summary of consultation results ...................................................................................................... 5 Besieged areas..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Suggested solutions ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Detainees ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Suggested solutions ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Shelling ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Suggested solutions ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Syrian Civil Society Platform ..................................................................................................... -

"An Army in All Corners": Assad's Campaign Strategy in Syria

APRIL 2015 CHRISTOPHER KOZAK MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 26 “AN ARMY IN ALL CORNERS” ASSAD’S CAMPAIGN STRATEGY IN SYRIA Cover: February 11, 2015A fighter loyal to Syria’s President Bashar Al-Assad hangs his picture as fellow fighters rest by a Syrian national flag after gaining control of the area in Deir al-Adas, a town south of Damascus, Daraa countryside February 10, 2015. Syrian government troops and their allies in the Lebanese group Hezbollah pressed a major offensive in southern Syria on Wednesday, taking new ground in a campaign against insurgents who pose one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Syrian state TV broadcast live from Deir al-Adas, a town some 30 km (19 miles) south of Damascus that it said had been captured. The sound of artillery being fired could be heard. The nearby town of Deir Maker was also captured, state TV said. Picture taken February 10, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2015 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2015 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org CHRISTOPHER KOZAK MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 26 “AN ARMY IN ALL CORNERS” ASSAD’S CAMPAIGN STRATEGY IN SYRIA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 26 | “AN ARMY IN ALL CORNERS” | CHRISTOPHER KOZAK | APRIL 2015 U.S.