Clostridioides-Difficile-Infection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Food Poisoning Toxins of Bacillus Cereus

toxins Review The Food Poisoning Toxins of Bacillus cereus Richard Dietrich 1,†, Nadja Jessberger 1,*,†, Monika Ehling-Schulz 2 , Erwin Märtlbauer 1 and Per Einar Granum 3 1 Department of Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Schönleutnerstr. 8, 85764 Oberschleißheim, Germany; [email protected] (R.D.); [email protected] (E.M.) 2 Department of Pathobiology, Functional Microbiology, Institute of Microbiology, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, 1210 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 3 Department of Food Safety and Infection Biology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, P.O. Box 5003 NMBU, 1432 Ås, Norway; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors have contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Bacillus cereus is a ubiquitous soil bacterium responsible for two types of food-associated gastrointestinal diseases. While the emetic type, a food intoxication, manifests in nausea and vomiting, food infections with enteropathogenic strains cause diarrhea and abdominal pain. Causative toxins are the cyclic dodecadepsipeptide cereulide, and the proteinaceous enterotoxins hemolysin BL (Hbl), nonhemolytic enterotoxin (Nhe) and cytotoxin K (CytK), respectively. This review covers the current knowledge on distribution and genetic organization of the toxin genes, as well as mechanisms of enterotoxin gene regulation and toxin secretion. In this context, the exceptionally high variability of toxin production between single strains is highlighted. In addition, the mode of action of the pore-forming enterotoxins and their effect on target cells is described in detail. The main focus of this review are the two tripartite enterotoxin complexes Hbl and Nhe, but the latest findings on cereulide and CytK are also presented, as well as methods for toxin detection, and the contribution of further putative virulence factors to the diarrheal disease. -

The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio In

microorganisms Review The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease Spase Stojanov 1,2, Aleš Berlec 1,2 and Borut Štrukelj 1,2,* 1 Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Biotechnology, Jožef Stefan Institute, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia * Correspondence: borut.strukelj@ffa.uni-lj.si Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 31 October 2020; Published: 1 November 2020 Abstract: The two most important bacterial phyla in the gastrointestinal tract, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, have gained much attention in recent years. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio is widely accepted to have an important influence in maintaining normal intestinal homeostasis. Increased or decreased F/B ratio is regarded as dysbiosis, whereby the former is usually observed with obesity, and the latter with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Probiotics as live microorganisms can confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. There is considerable evidence of their nutritional and immunosuppressive properties including reports that elucidate the association of probiotics with the F/B ratio, obesity, and IBD. Orally administered probiotics can contribute to the restoration of dysbiotic microbiota and to the prevention of obesity or IBD. However, as the effects of different probiotics on the F/B ratio differ, selecting the appropriate species or mixture is crucial. The most commonly tested probiotics for modifying the F/B ratio and treating obesity and IBD are from the genus Lactobacillus. In this paper, we review the effects of probiotics on the F/B ratio that lead to weight loss or immunosuppression. -

Hand Hygiene Solutions

PRODUCT OVERVIEWS Hand Hygiene Solutions Healing Hands Need Help, Too. Almost 80% of infectious Hand hygiene compliance Product selection matters diseases are transmitted rates are often very low Products containing aloe vera, via touch Outpatient clinics: Studies vitamin E and other emollients One of the most common have shown that hand hygiene can help to soothe and protect modes of transmission is frequency amongst clinic staff hands and even promote hand via the hands of healthcare ranges from 11-50%.2, 3 hygiene compliance.4 professionals.1 Designed for the demanding needs of healthcare professionals, Clorox Healthcare® provides a wide array of hand hygiene solutions formulated for frequent hand hygiene in healthcare settings. References 1. Tierno, P. The Secret Life of Germs. New York, NY, USA: Atria Books, 2001. 2. Kukanich KS, Kaur R, Freeman LC, Powell DA. Evaluation of a hand hygiene campaign in outpatient health care clinics. Am J Nurs. 2013 Mar;113(3):36-42. 3. Thompson D, Bowdey L, Brett M, Cheek, Using medical student observers of infection prevention, hand hygiene, and injection safety in outpatient settings: A cross-sectional survey. J Am J Infect. Control 2016; 44(4):374–380. 4. World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care Is Safer Care. 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144051/ (Accessed 22 February 2017) 5. CDC. “Handwashing: Clean Hands Save Lives-Show Me the Science-Why Wash Your Hands?” https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/why-handwashing.html (Accessed 15 March 2017). Hand hygiene is one of the most effective ways to stop the spread of germs and keep patients, staff and visitors safe.5 Our portfolio of hand hygiene solutions can be used to clean and soothe hands throughout your facility-from reception areas, to patient care areas to break rooms and offices. -

Drug-Resistant Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Methicillin

NEWS & NOTES Conference Summary pneumoniae can vary among popula- conference sessions was that statically tions and is influenced by local pre- sound methods of data collection that Drug-resistant scribing practices and the prevalence capture valid, meaningful, and useful of resistant clones. Conference pre- data and meet the financial restric- Streptococcus senters discussed the role of surveil- tions of state budgets are indicated. pneumoniae and lance in raising awareness of the Active, population-based surveil- Methicillin- resistance problem and in monitoring lance for collecting relevant isolates is the effectiveness of prevention and considered the standard criterion. resistant control programs. National- and state- Unfortunately, this type of surveil- Staphylococcus level epidemiologists discussed the lance is labor-intensive and costly, aureus benefits of including state-level sur- making it an impractical choice for 1 veillance data with appropriate antibi- many states. The challenges of isolate Surveillance otic use programs designed to address collection, packaging and transport, The Centers for Disease Control the antibiotic prescribing practices of data collection, and analysis may and Prevention (CDC) convened a clinicians. The potential for local sur- place an unacceptable workload on conference on March 12–13, 2003, in veillance to provide information on laboratory and epidemiology person- Atlanta, Georgia, to discuss improv- the impact of a new pneumococcal nel. ing state-based surveillance of drug- vaccine for children was also exam- Epidemiologists from several state resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae ined; the vaccine has been shown to health departments that have elected (DRSP) and methicillin-resistant reduce infections caused by resistance to implement enhanced antimicrobial Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). -

Ethanol Rins and Hand Sanitizer

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY NATIONAL VEHICLE AND FUEL EMISSIONS LABORATORY 2565 PLYMOUTH ROAD ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48105-2498 OFFICE OF AIR AND RADIATION May 11, 2020 Re: Ethanol RINs and Hand Sanitizer Production for EP3 Pathway Ethanol Facilities during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Dear Ethanol Producers: EPA administers the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program, including determining what volumes of fuel ethanol qualify for tradable credits (RINs) under the program. In 2014, as part of the RFS Program in 40 C.F.R. Part 80, we created the Efficient Producer Petition Process (EP3) as a streamlined process for corn starch and grain sorghum ethanol producers to demonstrate that their fuel satisfies the lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction requirements to qualify for RINs. Consistent with 40 C.F.R. § 80.1416, over 80 dry mill ethanol plants in the United States have been approved for EP3 pathways. Given the current 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), we understand that some consumers and health care professionals are currently experiencing difficulties accessing alcohol-based hand sanitizers. To enhance the availability of hand sanitizer products, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a number of temporary policies, including temporary guidance for producers of alcohol for hand sanitizer.1 Based on input from industry, we understand fuel ethanol facilities can quickly and significantly enhance the availability of alcohol suitable for hand sanitizer production. Ethanol production through an EP3 pathway is limited to 200-proof ethanol, whereas alcohol suitable for use as an ingredient in hand sanitizer (hand sanitizer alcohol) is commonly produced as 190-proof ethanol. -

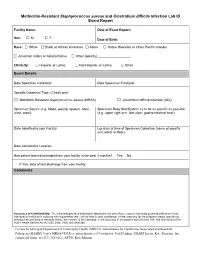

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Clostridium Difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report Facility Name: Date of Event Report: Sex: M F □ □ Date of Birth: Race: □ White □ Black or African American □ Asian □ Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander □ American Indian or Alaska Native □ Other [specify] __________________ Ethnicity: □ Hispanic or Latino □ Not Hispanic or Latino □ Other Event Details Date Specimen Collected: Date Specimen Finalized: Specific Organism Type: (Check one) □ Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) □ Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Specimen Source (e.g. blood, wound, sputum, bone, Specimen Body Site/System try to be as specific as possible urine, stool): (e.g. upper right arm, foot ulcer, gastrointestinal tract): Date Admitted to your Facility: Location at time of Specimen Collection (name of specific unit, ward, or floor): Date Admitted to Location: Has patient been discharged from your facility in the past 3 months? Yes No If Yes, date of last discharge from your facility: Comments Assurance of Confidentiality: The voluntarily provided information obtained in this surveillance system that would permit identification of any individual or institution is collected with a guarantee that it will be held in strict confidence, will be used only for the purposes stated, and will not otherwise be disclosed or released without the consent of the individual, or the institution in accordance with Sections 304, 306 and 308(d) of the Public Health Service Act (42 USC 242b, 242k, and 242m(d)). For use by Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH), Surveillance for Healthcare-Associated and Resistant Pathogens (SHARP) Unit’s MRSA/CDI Prevention Initiative (Coordinator: Gail Denkins, SHARP Intern: Kate Manton); fax completed forms to (517) 335-8263, ATTN: Kate Manton. -

Sporulation Evolution and Specialization in Bacillus

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/473793; this version posted March 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Research article From root to tips: sporulation evolution and specialization in Bacillus subtilis and the intestinal pathogen Clostridioides difficile Paula Ramos-Silva1*, Mónica Serrano2, Adriano O. Henriques2 1Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência, Oeiras, Portugal 2Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Oeiras, Portugal *Corresponding author: Present address: Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Marine Biodiversity, Leiden, The Netherlands Phone: 0031 717519283 Email: [email protected] (Paula Ramos-Silva) Running title: Sporulation from root to tips Keywords: sporulation, bacterial genome evolution, horizontal gene transfer, taxon- specific genes, Bacillus subtilis, Clostridioides difficile 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/473793; this version posted March 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Abstract Bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum are able to enter a developmental pathway that culminates with the formation of a highly resistant, dormant spore. Spores allow environmental persistence, dissemination and for pathogens, are infection vehicles. In both the model Bacillus subtilis, an aerobic species, and in the intestinal pathogen Clostridioides difficile, an obligate anaerobe, sporulation mobilizes hundreds of genes. -

Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel

Core Concepts for Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel 1 Presenter Russ Olmsted, MPH, CIC Director, Infection Prevention & Control Trinity Health, Livonia, MI Contributions by Heather M. Gilmartin, NP, PhD, CIC Denver VA Medical Center University of Colorado Laraine Washer, MD University of Michigan Health System 2 Learning Objectives • Outline the importance of effective hand hygiene for protection of healthcare personnel and patients • Describe proper hand hygiene techniques, including when various techniques should be used 3 Why is Hand Hygiene Important? • The microbes that cause healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) can be transmitted on the hands of healthcare personnel • Hand hygiene is one of the MOST important ways to prevent the spread of infection 1 out of every 25 patients has • Too often healthcare personnel do a healthcare-associated not clean their hands infection – In fact, missed opportunities for hand hygiene can be as high as 50% (Chassin MR, Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf, 2015; Yanke E, Am J Infect Control, 2015; Magill SS, N Engl J Med, 2014) 4 Environmental Surfaces Can Look Clean but… • Bacteria can survive for days on patient care equipment and other surfaces like bed rails, IV pumps, etc. • It is important to use hand hygiene after touching these surfaces and at exit, even if you only touched environmental surfaces Boyce JM, Am J Infect Control, 2002; WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care, WHO, 2009 5 Hands Make Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Other Microbes Mobile (Image from CDC, Vital Signs: MMWR, 2016) 6 When Should You Clean Your Hands? 1. Before touching a patient 2. -

Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Staphylococcus Aureus in Children

BRIEF REPORT Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in Children Gili Regev-Yochay, MD Context Widespread pneumococcal conjugate vaccination may bring about epidemio- Ron Dagan, MD logic changes in upper respiratory tract flora of children. Of particular significance may Meir Raz, MD be an interaction between Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, in view of the recent emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus. Yehuda Carmeli, MD, MPH Objective To examine the prevalence and risk factors of carriage of S pneumoniae Bracha Shainberg, PhD and S aureus in the prevaccination era in young children. Estela Derazne, MSc Design, Setting, and Patients Cross-sectional surveillance study of nasopharyn- geal carriage of S pneumoniae and nasal carriage of S aureus by 790 children aged 40 Galia Rahav, MD months or younger seen at primary care clinics in central Israel during February 2002. Ethan Rubinstein, MD Main Outcome Measures Carriage rates of S pneumoniae (by serotype) and S aureus; risk factors associated with carriage of each pathogen. TREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE AND Results Among 790 children screened, 43% carried S pneumoniae and 10% car- Staphylococcus aureus are com- ried S aureus. Staphylococcus aureus carriage among S pneumoniae carriers was 6.5% mon inhabitants of the upper vs 12.9% in S pneumoniae noncarriers. Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage among respiratory tract in children and S aureus carriers was 27.5% vs 44.8% in S aureus noncarriers. Only 2.8% carried both Sare responsible for common infec- pathogens concomitantly vs 4.3% expected dual carriage (P=.03). Risk factors for tions. Carriage of S aureus and S pneu- S pneumoniae carriage (attending day care, having young siblings, and age older than moniae can result in bacterial spread and 3 months) were negatively associated with S aureus carriage. -

Bacillus Cereus Pneumonia

‘Advances in Medicine and Biology’, Volume 67, 2013 Nova Science Publisher Inc., Editor: Berhardt LV To Alessia, my queen, and Giorgia, my princess Chapter BACILLUS CEREUS PNEUMONIA Vincenzo Savini* Clinical Microbiology and Virology, Spirito Santo Hospital, Pescara (PE), Italy ABSTRACT Bacillus cereus is a Gram positive/Gram variable environmental rod, that is emerging as a respiratory pathogen; particularly, pneumonia it causes may be serious and can resemble the anthrax disease. In fact, the organism is strictly related to the famous Bacillus anthracis, with which it shares genotypical, fenotypical, and pathogenic features. Treatment of B. cereus lower airway infections is becoming increasingly hard, due to the spread of multidrug resistance traits among members of the species. Hence, the present chapter’s scope is to shed a light on this bacterium’s lung pathogenicity, by depicting salient microbiological, epidemiological and clinical features it shows. Also, we would like to explore virulence determinants and resistance mechanisms that make B. cereus a life-threatening, potentially difficult-to-treat agent of airway pathologies. * Email: [email protected]. 2 Vincenzo Savini INTRODUCTION The genus Bacillus includes spore-forming species, strains of which are not usually considered to be clinically relevant when isolated from human specimens; in fact, these bacteria are known to be ubiquitously distributed in the environment and may easily contaminate culture material along with improperly handled sample collection devices (Miller, 2012; Brooks, 2001). Bacillus anthracis is the prominent agent of human pathologies within the genus Bacillus, although it is uncommon in most clinical laboratories (Miller, 2012). It is a frank pathogen, as it causes skin and enteric infections; above all, however, it is responsible for a serious lung disease (the ‘anthrax’) that is frequently associated with bloodstream infection and a high mortality rate (Frankard, 2004). -

Statistical Evaluation of Diagnostic Tests – Part 2 [Pre-Test and Post-Test Probability and Odds, Likelihood Ratios, Receiver

86 Journal of The Association of Physicians of India ■ Vol. 65 ■ July 2017 STATISTICS FOR RESEARCHERS Statistical Evaluation of Diagnostic Tests – Part 2 [Pre-test and post-test probability and odds, Likelihood ratios, Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve, Youden’s Index and Diagnostic test biases] NJ Gogtay, UM Thatte Introduction Understanding Probability From the example, it follows that and Odds and the Odds = p/1-p, where p is the n the previous article on probability of the event occurring. the statistical evaluation Relationship between the I Probability, on the other hand, of diagnostic tests –Part 1, we Two is given by the formula understood the measures of sensitivity, specificity, positive Let us understand probability p = Odds/1+Odds and negative predictive values. and odds with the example of The use of these metrices stems a drug producing bleeding in Bayesian Statistics, Pre- from the fact that no diagnostic 10/100 patients treated with it. Test Probability and Pre- test is ever perfect and every time The probability of bleeding will Test Odds we carry out a test, it will yield be 10/100 [10%], while the odds of one of four possible outcomes– bleeding will be 10/90 [11%]. This A clinician often suspects that true positive, false positive, true is because odds is defined as the a patient has the disease even negative or false negative. The 2 x probability of the event occurring before he orders a test [screening 2 table [Table 1] gives each of these divided by the probability of or diagnostic] on the patient. For four possibilities along with their the event not occurring.2 Thus, example, when a patient who is mathematical calculations when a every odds can be expressed as a chronic smoker and presents new test is compared with a gold probability and every probability with cough and weight loss of a standard test.1 as odds as these are two ways of six-month duration, the suspicion In this article, the second in explaining the same concept. -

Common Commensals

Common Commensals Actinobacterium meyeri Aerococcus urinaeequi Arthrobacter nicotinovorans Actinomyces Aerococcus urinaehominis Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus Actinomyces bernardiae Aerococcus viridans Arthrobacter oryzae Actinomyces bovis Alpha‐hemolytic Streptococcus, not S pneumoniae Arthrobacter oxydans Actinomyces cardiffensis Arachnia propionica Arthrobacter pascens Actinomyces dentalis Arcanobacterium Arthrobacter polychromogenes Actinomyces dentocariosus Arcanobacterium bernardiae Arthrobacter protophormiae Actinomyces DO8 Arcanobacterium haemolyticum Arthrobacter psychrolactophilus Actinomyces europaeus Arcanobacterium pluranimalium Arthrobacter psychrophenolicus Actinomyces funkei Arcanobacterium pyogenes Arthrobacter ramosus Actinomyces georgiae Arthrobacter Arthrobacter rhombi Actinomyces gerencseriae Arthrobacter agilis Arthrobacter roseus Actinomyces gerenseriae Arthrobacter albus Arthrobacter russicus Actinomyces graevenitzii Arthrobacter arilaitensis Arthrobacter scleromae Actinomyces hongkongensis Arthrobacter astrocyaneus Arthrobacter sulfonivorans Actinomyces israelii Arthrobacter atrocyaneus Arthrobacter sulfureus Actinomyces israelii serotype II Arthrobacter aurescens Arthrobacter uratoxydans Actinomyces meyeri Arthrobacter bergerei Arthrobacter ureafaciens Actinomyces naeslundii Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus Arthrobacter variabilis Actinomyces nasicola Arthrobacter citreus Arthrobacter viscosus Actinomyces neuii Arthrobacter creatinolyticus Arthrobacter woluwensis Actinomyces odontolyticus Arthrobacter crystallopoietes