The Restoration of Austrian Universities After World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die Figuren des Helmut Qualtinger in der Tradition des Wiener Volksstücks“ Verfasser Elias Natmessnig angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. A 317 Studienblatt: Studienrichtung lt. Theater- Film- und Medienwissenschaften Studienblatt: Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Christian Schulte 1 2 Inhalt Inhalt........................................................................................................................................... 3 1) Einleitung............................................................................................................................... 7 2) Inspirationen der Jugend...................................................................................................... 10 3) Das Volksstück .................................................................................................................... 15 3.1) Das Wiener Volksstück................................................................................................. 18 3.1.1) Johann Nepomuk Nestroy...................................................................................... 19 3.1.2) Zwischen Nestroy und Kraus................................................................................. 22 3.1.3) Karl Kraus.............................................................................................................. 24 3.2) Die Erneuerer ............................................................................................................... -

The Waldheim Phenomenon in Austria

Demokratiezentrum Wien Onlinequelle: www.demokratiezentrum.org Printquelle: Mitten, Richard: The Politics of the Antisemitic Prejudice. The Waldheim Phenomenon in Austria. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado 1992 (Chapter 1 and 8) Richard Mitten THE POLITICS OF ANTISEMITIC PREJUDICE : THE WALDHEIM PHENOMENON IN AUSTRIA Table of Contents: Acknowledgments Chapter One: Introduction: “Homo austriacus” agonistes Chapter Two: Austria Past and Present Chapter Three: From Election Catatonia to the “Waldheim Affair” Chapter Four: “What did you do in the war, Kurt?” Chapter Five: Dis“kurt”esies: Waldheim and the Language of Guilt Chapter Six: The Role of the World Jewish Congress Chapter Seven: The Waldheim Affair in the United States Chapter Eight: The “Campaign” against Waldheim and the Emergence of the Feindbild Chapter Nine: When “The Past” Catches Up 1 Autor/Autorin: Richard Mitten • The Campaign against Waldheim and the Emergence of the Feindbild Printquelle: Mitten, Richard: The Politics of the Antisemitic Prejudice. The Waldheim Phenomenon in Austria. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado 1992 (Chapter 1 and 8) • Onlinequelle: www.demokratiezentrum.org Demokratiezentrum Wien Onlinequelle: www.demokratiezentrum.org Printquelle: Mitten, Richard: The Politics of the Antisemitic Prejudice. The Waldheim Phenomenon in Austria. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado 1992 (Chapter 1 and 8) Introduction: “Homo austriacus” agonistes Gaiety, a clear conscience, the happy deed, the confidence in the future---all these depend, for the individual as well as for a people, on there being a line that separates the forseeable, the light, from the unilluminable and the darkness; on one’s knowing just when to forget, when to remember; on one’s instinctively feeling when necessary to perceive historically, when unhistorically. -

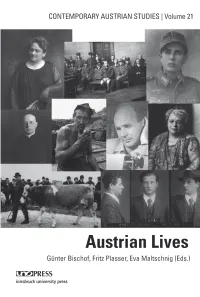

CAS21 for Birgit-No Marks

Austrian Lives Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser, Eva Maltschnig (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 21 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2012 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America. Book and cover design: Lauren Capone Cover photo credits given on the following pages: 33, 72, 119, 148, 191, 311, 336, 370, 397 Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press: by Innsbruck University Press: ISBN: 9781608010929 ISBN: 9783902811615 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lauren Capone University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Sándor Kurtán Universität Graz Corvinus University Budapest Peter Berger Günther Pallaver -

The Research Project ‘Cold War Discourses

ILCEA Revue de l’Institut des langues et cultures d'Europe, Amérique, Afrique, Asie et Australie 16 | 2012 La culture progressiste à l’époque de la guerre froide The Research Project ‘Cold War Discourses. Political Configurations and their Contexts in Austrian Literature between 1945 and 1966’ Das Forschungsprojekt ‚Diskurse des Kalten Krieges. Politische Konfigurationen und deren Kontexte in österrreichischer Literatur zwischen 1945 und 1966’ Stefan Maurer and Doris Neumann-Rieser Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ilcea/1451 DOI: 10.4000/ilcea.1451 ISSN: 2101-0609 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version ISBN: 978-2-84310-232-5 ISSN: 1639-6073 Electronic reference Stefan Maurer and Doris Neumann-Rieser, “The Research Project ‘Cold War Discourses. Political Configurations and their Contexts in Austrian Literature between 1945 and 1966’”, ILCEA [Online], 16 | 2012, Online since 04 July 2012, connection on 22 March 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ ilcea/1451 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ilcea.1451 This text was automatically generated on 22 March 2021. © ILCEA The Research Project ‘Cold War Discourses. Political Configurations and their... 1 The Research Project ‘Cold War Discourses. Political Configurations and their Contexts in Austrian Literature between 1945 and 1966’ Das Forschungsprojekt ‚Diskurse des Kalten Krieges. Politische Konfigurationen und deren Kontexte in österrreichischer Literatur zwischen 1945 und 1966’ Stefan Maurer and Doris Neumann-Rieser 1 The Research Project -

Austrian Lives

Austrian Lives Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser, Eva Maltschnig (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 21 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2012 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America. Book and cover design: Lauren Capone Cover photo credits given on the following pages: 33, 72, 119, 148, 191, 311, 336, 370, 397 Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press: by Innsbruck University Press: ISBN: 9781608010929 ISBN: 9783902811615 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lauren Capone University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Sándor Kurtán Universität Graz Corvinus University Budapest Peter Berger Günther Pallaver -

Holocaust Memory for the Millennium

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Royal Holloway - Pure HHoollooccaauusstt MMeemmoorryy ffoorr tthhee MMiilllleennnniiuumm LLaarriissssaa FFaayyee AAllllwwoorrkk Royal Holloway, University of London Submission for the Examination of PhD History 1 I Larissa Allwork, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: L.F. Allwork Date: 15/09/2011 2 Abstract Holocaust Memory for the Millennium fills a significant gap in existing Anglophone case studies on the political, institutional and social construction of the collective memory of the Holocaust since 1945 by critically analyzing the causes, consequences and ‘cosmopolitan’ intellectual and institutional context for understanding the Stockholm International Forum on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research (26 th January-28 th January 2000). This conference was a global event, with ambassadors from 46 nations present and attempted to mark a defining moment in the inter-cultural construction of the political and institutional memory of the Holocaust in the United States of America, Western Europe, Eastern Europe and Israel. This analysis is based on primary documentation from the London (1997) and Washington (1998) restitution conferences; Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research primary sources; speeches and presentations made at the Stockholm International Forum 2000; oral history interviews with a cross-section of British delegates to the conference; contemporary press reports, as well as pre-existing scholarly literature on the history, social remembrance and political and philosophical implications of the perpetration of the Holocaust and genocides. -

Vol. Xxiv/Xxv (2018/2019) No 31–32

THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSLETTER OF COMMUNIST STUDIES Der Internationale Newsletter der Kommunismusforschung La newsletter internationale des recherches sur le communisme Международный бюллетень исторических исследований коммунизма La Newsletter Internacional de Estudios sobre el Comunismo A Newsletter Internacional de Estudos sobre o Comunismo Edited by Bernhard H. Bayerlein and Gleb J. Albert VOL. XXIV/XXV (2018/2019) NO 31–32 Published by The European Workshop of Communist Studies With Support of the Institute of Social Movements and the Library of the Ruhr University Bochum ISSN 1862-698X http://incs.ub.rub.de The International Newsletter of Communist Studies XXIV/XXV (2018/19), nos. 31-32 2 Editors Bernhard H. Bayerlein Institute of Social Movements (ISB), University of Bochum, Germany [email protected] / [email protected] Gleb J. Albert Department of History, University of Zurich [email protected] Board of Correspondents Lars Björlin (Stockholm) Ottokar Luban (Berlin) Kasper Braskén (Åbo) Kevin McDermott (Sheffield) Hernán Camarero (Buenos Aires) Brendan McGeever (London) Cosroe Chaqueri † (Paris) Kevin Morgan (Manchester) Sonia Combe (Paris) Timur Mukhamatulin (New Brunswick) Mathieu Denis (Paris/Montréal) Manfred Mugrauer (Wien) Jean-François Fayet (Fribourg) Maria Luisa Nabinger (Rio de Janeiro) Jan Foitzik (Berlin) José Pacheco Pereira (Lisbon) Daniel Gaido (Córdoba, Argentina) Fredrik Petersson (Åbo/Stockholm) José Gotovitch (Bruxelles) Adriana Petra (Buenos Aires) Sobhanlal Datta Gupta (Calcutta) Kimmo Rentola -

QUASI JEDERMANN Helmut Qualtinger, Der Menschenimitator Mit Texten Von Carl Merz Und Helmut Qualtinger Musik Von Wiener Blond

MATERIALMAPPE QUASI JEDERMANN Helmut Qualtinger, der Menschenimitator Mit Texten von Carl Merz und Helmut Qualtinger Musik von Wiener Blond Ansprechperson für weitere Informationen Mag.ᵃ Julia Perschon | Theatervermittlung T +43 2742 90 80 60 694 | M +43 664 604 99 694 [email protected] | www.landestheater.net INHALTSVERZEICHNIS VORWORT 1. ZUR PRODUKTION ……………………………………………………….... 4 2. EINE HOMMAGE AN HELMUTQUALTINGER……………………………… 5 3. HELMUT QUALTINGER – BIOGRAFIE ……………………………………. 6 4. PROGRAMM QUASI JEDERMANN ………………………………………... 7 5. TEXTAUSZUG „DER HERR KARL“…………………….……………………. 8 6. ENTSTEHUNG UND INHALT VON „DER HERR KARL“ …………………. 9 7. HISTORISCHE EREIGNISSE UND PERSONEN BEI „DER HERR KARL“ 12 8. SONG AUS QUASI JEDERMANN ………………………………………… 15 9. IMPULSTEXT 1 – INTERVIEW MIT PETER TURRINI ………………… 16 10. IMPULSTEXT 2 – ÖSTERREICHS GESICHT ……………………….... 18 11. NACH DEM THEATERBESUCH ………………………………………... 19 2 VORWORT Liebe Pädagoginnen und Pädagogen, liebe Besucherinnen und Besucher, bis heute gilt Helmut Qualtinger als die Verkörperung der österreichischen Seele. Sein Wiener Schmäh, dessen sprachliche Wurzeln bis zu Ödön von Horváth, Karl Kraus und Johann Nepomuk Nestroy reichen, sorgte für Begeisterungsstürme bei seinem Publikum. Helmut Qualtinger, den das ganze Land liebevoll den „Quasi“ nannte, war ein Stachel im Fleisch der spießbürgerlichen Nachkriegszeit. Witz und bitterböser Tiefsinn, treffsichere Pointe und Verzweiflung an den herrschenden Zuständen lagen bei ihm nah beieinander. Mit dem Monolog „Der Herr Karl“ von 1961 setzten Qualtinger und Carl Merz dem typischen Mitläufer und gesinnungslosen Opportunisten ein literarisches Denkmal. „Der Herr Karl“ löste eine nationale Kontroverse aus und wurde, weit über die österreichischen Grenzen hinaus, zur Kultfigur. „Quasi Jedermann“ ist eine musikalische Hommage an den Schriftsteller, Schauspieler, Kabarettisten und unvergleichlichen „Menschenimitator“, wie Helmut Qualtinger sich selbst bezeichnete. -

Conc Erts && So Unds Museumss && Exhi Biittions

CONCERTS & SOUNDS MUSEUMS & EXHIBITIONS OPERA & MUSICAL THEATRE THEATRE & DANCE Joachim Meyerhoff in Antigone by Sophokles Contents CONCERTS & SOUNDS 5 MUSEUMS & EXHIBITIONS 19 OPERA & MUSICAL 69 THEATRE THEATRE & DANCE 79 Concept & Coordination: Julia Patuzzi ESR OFFICE All rights reserved by the Layout: Barbara Biegl Neutorgasse 9, 1010 Vienna, Austria ESR – European Society of Radiology Printed by: agensketterl Druckerei GmbH Phone: + 43 1 533 40 64-0 No responsibility is accepted for the Date of printing: February 2017 E-Mail: [email protected] correctness of the information. myESR.org Burgtheater, around 1900 Photochrom print (colour photo lithograph) Welcome to ECR Arts & Culture! The European Society of Radiology is proud and happy to present you with an extensive and distinguished cultural programme for your time at ECR 2017. Vienna fulfils anew its reputation as cultural capital of the world, providing a boundless variety of artistic endeavours. Be it the virtuosity of Vienna’s famous orchestras led by the world’s leading conductors, the transcendent beauty of the opera, or the sheer abundance of fine arts ranging from ancient Greek sculptures to Baroque paintings, from Art Nouveau furniture to installations representing visionary views of the 21st century – there is sure to be found something for every artistic taste. On the following pages you will find details and information regarding opera, concerts, museums, exhibitions, theatre and dance. We hope this brochure will help you make the most of your spare time during the congress. Enjoy your stay in Vienna! Julia Patuzzi ESR Office – Department of PR & Media Stefan Vladar Konzerthaus Musikverein Porgy & Bess Arena Gasometer Szene Wien Arnold Schönberg Center Haus der Musik Mozarthaus Vienna CONCERTS & SOUNDS 5 Isabelle van Keulen 6 Classical Music Concerts & Sounds Classical Music March 1, 19:30 Wiener KammerOrchester, Konzerthaus conductor Stefan Vladar Isabelle van Keulen, violin The Wiener Konzerthaus, inaugurated in 1913, is W.A. -

Helmut Qualtinger Oder: Die Demaskierung Einer Volksseele

Helmut Qualtinger oder: die Demaskierung einer Volksseele. Eine Abhandlung des Werks „Herr Karl“ zum politischen und gesellschaftlichen Zeitgeschehen und dessen Medienecho. D I P L O M A R B E I T Zur Erlangung des Magistergrades der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Wien eingereicht von Sabine Krangler Wien, November, 2006 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. EINLEITUNG ................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Forschungsstand und bisherige Ergebnisse................................................... 5 1.2 Fragestellung................................................................................................. 7 1.3 Methodisches Vorgehen.............................................................................. 10 2. PORTRÄT QUALTINGER........................................................................... 11 2.1 Tabellarische Kurzbiographie ..................................................................... 11 2.2 Die kleinbürgerliche Herkunft: Qualtingers Jugend ................................... 19 2.3 Das erste Skandalstück: „Jugend ohne Schranken“.................................... 22 2.3.1 Entstehungsgeschichte und Inhalt........................................................ 22 2.3.2 Gesellschaftl. und pol. Rahmenbedingungen....................................... 24 2.3.3 Reaktionen zur Uraufführung .............................................................. 26 2.4 Die zeitkritischen Kabarettjahre (1947-61)................................................ -

The Major Literary Polemicso Karl Kraus

Durham E-Theses The major literary polemicso Karl Kraus Carr, Gilbert J. How to cite: Carr, Gilbert J. (1972) The major literary polemicso Karl Kraus, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7938/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT This study of the most important of Kraus1s polemics against literary contemporaries centres on the relation of language and character. Any attempt simply to extract his opinions or to measure his verdicts against accepted critical opinion has been eschewed, as a misinterpretation of Kraus's whole purpose. Since his polemics were two- pronged attacks - on style and character - his conceptions of language and personality are outlined, and also related to his demand that the polemicist should embody artistic values. As a background to his demand for unity of man and work, the construction of his persona and the dualism in his thought and its implications for his critical procedure are discussed. -

UNIVERSITY of CALGARY Mocking Hitler: Nazi Speech & Humour In

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Mocking Hitler: Nazi Speech & Humour in Contemporary German Culture by Annika Orich A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE INTERDISCIPLINARY DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC, SLAVIC AND EAST ASIAN STUDIES and DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER, 2008 © Annika Orich 2008 ISBN: 978-0-494-51133-6 UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES The undersigned certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance, a thesis entitled “Mocking Hitler: Nazi Speech & Humour in Contemporary German Culture” submitted by Annika Orich in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the interdisciplinary degree of Master of Arts. 6XSHUYLVRUDr. Florentine Strzelczyk, GSEA &R6XSHUYLVRU, Dr. Adrienne Kertzer, English Dr. Michael Taylor, GSEA Dr. Lorraine Markotic, Faculty of Humanities 'DWH ii $EVWUDFW Mocking Hitler is by now an integral part of Germany’s contemporary culture of remembrance. Germans ridicule their former leader and his fellow myrmidons in jokes, films, comics, plays, cabaret, and anti-neo-Nazi satire. Yet, instead of making fun of the historic individual, Germans generally deride Hitler’s (self-)portrayal as the )KUHU and his mythological afterlife as the incarnation of absolute evil – a perception that is embodied by representations of Hitler the orator and Nazi speeches in general. On the basis of different examples of humour about Nazi speechmaking, this thesis identifies the reasons and functions that ridicule plays in Germans’ coming to terms with the Nazi past as well as its problematic and beneficial implications. While humour, on the one hand, demythologizes and exposes Hitler, it serves Germans, on the other hand, as a medium to normalize the memory of Hitler and to distance themselves from their perpetrator past.