Who Were the Daughters of Allah?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(S): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature Author(s): John Day Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Sep., 1986), pp. 385-408 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3260509 . Accessed: 11/05/2013 22:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.207.2.50 on Sat, 11 May 2013 22:44:00 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JBL 105/3 (1986) 385-408 ASHERAH IN THE HEBREW BIBLE AND NORTHWEST SEMITIC LITERATURE* JOHN DAY Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University, England, OX2 6QA The late lamented Mitchell Dahood was noted for the use he made of the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts in the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible. Although many of his views are open to question, it is indisputable that the Ugaritic and other Northwest Semitic texts have revolutionized our understanding of the Bible. One matter in which this is certainly the case is the subject of this paper, Asherah.' Until the discovery of the Ugaritic texts in 1929 and subsequent years it was common for scholars to deny the very existence of the goddess Asherah, whether in or outside the Bible, and many of those who did accept her existence wrongly equated her with Astarte. -

Arsu and ‘Azizu a Study of the West Semitic "Dioscuri" and the Cods of Dawn and Dusk by Finn Ove Hvidberg-Hansen

’Arsu and ‘Azizu A Study of the West Semitic "Dioscuri" and the Cods of Dawn and Dusk By Finn Ove Hvidberg-Hansen Historiske-filosofiske Meddelelser 97 Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters DET KONGELIGE DANSKE VIDENSKABERNES SELSKAB udgiver følgende publikationsrækker: THE ROYAL DANISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND LETTERS issues the following series of publications: Authorized Abbreviations Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser, 8° Hist.Fil.Medd.Dan.Vid.Selsk. (printed area 1 75 x 104 mm, 2700 units) Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter, 4° Hist.Filos.Skr.Dan.Vid.Selsk. (History, Philosophy, Philology, (printed area 2 columns, Archaeology, Art History) each 199 x 77 mm, 2100 units) Matematisk-fysiske Meddelelser, 8° Mat.Fys.Medd.Dan.Vid.Selsk. (Mathematics, Physics, (printed area 180 x 126 mm, 3360 units) Chemistry, Astronomy, Geology) Biologiske Skrifter, 4° Biol.Skr. Dan. Vid.Selsk. (Botany, Zoology, Palaeontology, (printed area 2 columns, General Biology) each 199 x 77 mm, 2100 units) Oversigt, Annual Report, 8° Overs. Dan.Vid.Selsk. General guidelines The Academy invites original papers that contribute significantly to research carried on in Denmark. Foreign contributions are accepted from temporary residents in Den mark, participants in a joint project involving Danish researchers, or those in discussion with Danish contributors. Instructions to authors Manuscripts from contributors who are not members of the Academy will be refereed by two members of the Academy. Authors of papers accepted for publication will re ceive galley proofs and page proofs; these should be returned promptly to the editor. Corrections other than of printer's errors will be charged to the author(s) insofar as the costs exceed 15% of the cost of typesetting. -

Michael Defeats the Dragon

THE REVELATION OF JOHN Bible Study 31 Study by Lorin L Cranford Text: Rev. 12:7-12 All rights reserved © QUICK LINKS 1. What the text meant. Exegesis of the Text: Historical Aspects: A. War between Michael and Satan, vv. 7-9 External History B. Declaration of victory, vv. 10-12 Internal History Literary Aspects: Genre 2. What the text means. Literary Setting Literary Structure Michael Defeats the Dragon Greek NT Gute Nachricht Bibel NRSV NLT 7 Καὶ ἐγένετο πόλεμος ἐν 7 Dann brach im Himmel 7 And war broke out in 7 Then there was war τῷ οὐρανῷ, ὁ Μιχαὴλ καὶ οἱ ein Krieg aus. Michael mit heaven; Michael and his an- in heaven. Michael and the ἄγγελοι αὐτοῦ τοῦ πολεμῆσαι seinen Engeln kämpfte gegen gels fought against the drag- angels under his command μετὰ τοῦ δράκοντος. καὶ ὁ den Drachen. Der Drache mit on. The dragon and his angels fought the dragon and his δράκων ἐπολέμησεν καὶ οἱ seinen Engeln wehrte sich; 8 fought back, 8 but they were angels. 8 And the dragon ἄγγελοι αὐτοῦ, 8 καὶ οὐκ aber er konnte nicht stand- defeated, and there was no lost the battle and was forced ἴσχυσεν οὐδὲ τόπος εὑρέθη halten. Samt seinen Engeln longer any place for them in out of heaven. 9 This great αὐτῶν ἔτι ἐν τῷ οὐρανῷ. musste er seinen Platz im heaven. 9 The great dragon dragon -- the ancient serpent 9 καὶ ἐβλήθη ὁ δράκων ὁ Himmel räumen. 9 Der große was thrown down, that ancient called the Devil, or Satan, μέγας, ὁ ὄφις ὁ ἀρχαῖος, ὁ Drache wurde hinunterg- serpent, who is called the the one deceiving the whole καλούμενος Διάβολος καὶ estürzt! Er ist die alte Sch- Devil and Satan, the deceiver world -- was thrown down to ὁ Σατανᾶς, ὁ πλανῶν τὴν lange, die auch Teufel oder of the whole world—he was the earth with all his angels. -

Inquiry Into the Status of the Human Right to Freedom of Religion Or Belief

Inquiry into the status of the Human Right to Freedom of Religion or Belief Submission: Inquiry into the status of the human right to freedom of religion or belief This purpose of this submission is to raise the committee’s awareness that Islam: - militates against “the enjoyment of freedom of religion or belief” - incites to “violations or abuses” of religious freedom - is antithetical and inimical to the “protection and promotion of freedom of religion or belief” Any inquiry into “the human right to freedom of religion or belief” which avoids examining arguably the largest global threat to those freedoms would be abdicating its responsibility to fully inform its stakeholders. Whether it is the nine Islamic countries in the top ten of the World Watch List of Christian Persecution(1), crucifix-wearing “Christians in Sydney fac(ing) growing persecution at the hands of Muslim gangs”(2) or the summary execution of those who blaspheme or apostatise(3), Islam, in practice and in doctrine, militates against “the human right to freedom of religion or belief”. The purpose of this submission is not to illustrate “the nature and extent of (Islamic) violations and abuses of this right” [which are well-documented elsewhere(4)] but to draw the committee’s attention to the Islamic doctrinal “causes of those violations or abuses”. An informed understanding of Islam is crucial to effectively addressing potential future conflicts between Islamic teachings which impact negatively on “freedom of religion or belief” and those Western freedoms we had almost come to take for granted, until Islam came along to remind us that they must be ever fought for. -

Lesson 11 ELIJAH DEFEATS 450 PROPHETS of BAAL with 1 PRAYER Memory Verse: Psalm 54:1-2 God, Save Me Because of Who You Are

Q7 – God is Good at Victory! Parent Teaching Guide God wins the victory! We are studying Old Testament battle stories. These stories show us over and over again that God has the power and God wins the victory for His people when they follow His commandments (have faith in Him). We will study Jesus’ triumph over death, which brings us the victory of salvation. We can be victorious if we remain faithful to God and to the sacrifice of His son. God never promises that our lives will be easy. He does promise us victory through Christ if we trust Him. Date: Dec 13-19, 2020 Lesson 11 ELIJAH DEFEATS 450 PROPHETS OF BAAL WITH 1 PRAYER Memory Verse: Psalm 54:1-2 God, save me because of who You are. By Your strength show that I am innocent. Hear my prayer, God. Listen to what I say. Text: 1 Kings 18 King Ahab and Queen Jezebel were very wicked. They did not worship God, they worshiped Baal. When the prophet Elijah went to them and told them of their sin, they thought the prophets of Baal could defeat God’s prophet. God was able to light the alter even after it had been soaked with water. Baal could not. Isn’t God powerful! Talk to your child about God’s power. He can defeat any false god is we only let him. If we pray and let Him have control, He will defeat our enemies and keep us safe. Facts to Know PRAISE & PRAYER Show pictures of people praying. -

Idolatry in the Ancient Near East1

Idolatry in the Ancient Near East1 Ancient Near Eastern Pantheons Ammonite Pantheon The chief god was Moloch/Molech/Milcom. Assyrian Pantheon The chief god was Asshur. Babylonian Pantheon At Lagash - Anu, the god of heaven and his wife Antu. At Eridu - Enlil, god of earth who was later succeeded by Marduk, and his wife Damkina. Marduk was their son. Other gods included: Sin, the moon god; Ningal, wife of Sin; Ishtar, the fertility goddess and her husband Tammuz; Allatu, goddess of the underworld ocean; Nabu, the patron of science/learning and Nusku, god of fire. Canaanite Pantheon The Canaanites borrowed heavily from the Assyrians. According to Ugaritic literature, the Canaanite pantheon was headed by El, the creator god, whose wife was Asherah. Their offspring were Baal, Anath (The OT indicates that Ashtoreth, a.k.a. Ishtar, was Baal’s wife), Mot & Ashtoreth. Dagon, Resheph, Shulman and Koshar were other gods of this pantheon. The cultic practices included animal sacrifices at high places; sacred groves, trees or carved wooden images of Asherah. Divination, snake worship and ritual prostitution were practiced. Sexual rites were supposed to ensure fertility of people, animals and lands. Edomite Pantheon The primary Edomite deity was Qos (a.k.a. Quas). Many Edomite personal names included Qos in the suffix much like YHWH is used in Hebrew names. Egyptian Pantheon2 Egyptian religion was never unified. Typically deities were prominent by locale. Only priests worshipped in the temples of the great gods and only when the gods were on parade did the populace get to worship them. These 'great gods' were treated like human kings by the priesthood: awakened in the morning with song; washed and dressed the image; served breakfast, lunch and dinner. -

The Relationship of Yahweh and El: a Study of Two Cults and Their Related Mythology

Wyatt, Nicolas (1976) The relationship of Yahweh and El: a study of two cults and their related mythology. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2160/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] .. ýýý,. The relationship of Yahweh and Ell. a study of two cults and their related mythology. Nicolas Wyatt ý; ý. A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy rin the " ®artänont of Ssbrwr and Semitic languages in the University of Glasgow. October 1976. ý ý . u.: ý. _, ý 1 I 'Preface .. tee.. This thesis is the result of work done in the Department of Hebrew and ': eraitia Langusgee, under the supervision of Professor John rdacdonald, during the period 1970-1976. No and part of It was done in collaboration, the views expressed are entirely my own. r. .e I should like to express my thanks to the followings Professor John Macdonald, for his assistance and encouragement; Dr. John Frye of the Univeritty`of the"Witwatersrandy who read parts of the thesis and offered comments and criticism; in and to my wife, whose task was hardest of all, that she typed the thesis, coping with the peculiarities of both my style and my handwriting. -

The Concept of God (Allah) in Islam Abdulkareem Ahmad Tijjani, Ph.D

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF EDUCATIONAL BENCHMARK (IJEB), eISSN: Benchmark Journals 2489-0170pISSN:2489-4162 University of Uyo The Concept of God (Allah) in Islam Abdulkareem Ahmad Tijjani, Ph.D Department of Islamic Studies Federal College of Education, Kano Abstract Believing in God (Allah) is the Central focus of all religions. The concept of God of each religion provides the distinguishing difference between one religion and the other. In this paper, attempt is made to present the concept of God in Islam. The pillars of Islam, the articles of faith, and the confession of faith are succinctly presented. Its significance lies in identifying the conception and characteristics of God – Allah in Islam.These features differentiate Islamic monotheism from the doctrines of God in other religions. Keywords: Allah, Al-Tawhid, Articles of Faith, Al-Ghayb, the Kalimah Introduction The teachings of Islam could be categorized into two parts; the theoretical aspects which deal with the belief system of Islam, and the practical aspects which deal with the rituals such as prayer, zakat, fasting, jihad, etc. The theoretical aspects of Islam is the pivot around which the Islamic concept of God revolves. It centres on the belief in ‘al-Tawhid’ i.e. the oneness of Allah, and the articles of faith. The belief system of Islam is called usul-al- din. The word usul is the plural of asl which means a root or a principle. The practical aspects which is called ahkam, means, the ordinances and regulations of Islam. These aspects are referred to in the glorious Qur’an as Iman and Amal, i.e. -

Between the Cults of Syria and Arabia: Traces of Pagan Religion at Umm Al-Jimål

!"#$%&"%'#(")*%+!"$,""-%$."%/01$)%23%45#(6%6-&%7#68(69%:#6;")%23%<6=6-%>"1(=(2-%6$% % ?@@%61AB(@61*C%!"#$%&'(%)("*&(+%'",-.(/)$(0-1*/&,2,3.(,4(5,-$/)(6D%7@@6-9% % E"F6#$@"-$%23%7-$(G0($(")%23%B2#&6-%HIJJKL9%MNNAMKMD% Bert de Vries Bert de Vries Department of History Calvin College Grand Rapids, MI 49546 U.S.A. Between the Cults of Syria and Arabia: Traces of Pagan Religion at Umm al-Jimål Introduction Such a human construction of religion as a so- Umm al-Jimål ’s location in the southern Hauran cial mechanism to achieve security does not pre- puts it at the intersection of the cultures of Arabia to clude the possibility that a religion may be based the south and Syria to the north. While its political on theological eternal verities (Berger 1969: 180- geography places it in the Nabataean and Roman 181). However, it does open up the possibility of an realms of Arabia, its cultural geography locates it archaeology of religion that transcends the custom- in the Hauran, linked to the northern Hauran. Seen ary descriptions of cult centers and cataloguing of on a more economic cultural axis, Umm al-Jimål altars, statues, implements and decorative elements. is between Syria as Bilåd ash-Shåm, the region of That is, it presupposes the possibility of a larger agricultural communities, and the Badiya, the re- interpretive context for these “traces” of religion gion of pastoral nomad encampments. Life of soci- using the methodology of cognitive archaeology. ety on these intersecting axes brought a rich variety The term “traces” is meant in the technical sense of economic, political and religious cross-currents of Assmann’s theory of memory (2002: 6-11). -

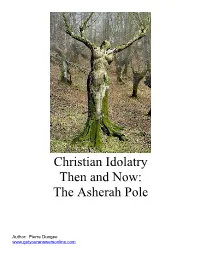

The Asherah Pole

Christian Idolatry Then and Now: The Asherah Pole Author: Pierre Dungee www.getyouranswersonline.com In this short book, we are going to look at the Asherah pole. Just so we have a working knowledge of idolatry, let’s look at what and idol is defined as: noun 1. a material object, esp a carved image, that is worshipped as a god 2. Christianity Judaism any being (other than the one God) to which divine honour is paid 3. a person who is revered, admired, or highly loved We also have the origin of this word, so let’s take a look at it here: o mid-13c., "image of a deity as an object of (pagan) worship," o from Old French idole "idol, graven image, pagan god," o from Late Latin idolum "image (mental or physical), form," used in Church Latin for "false god," o from Greek eidolon "appearance, reflection in water or a mirror," later "mental image, apparition, phantom,"also "material image, statue," from eidos "form" (see - oid). o Figurative sense of "something idolized" is first recorded 1560s (in Middle English the figurative sense was "someone who is false or untrustworthy"). Meaning"a person so adored" is from 1590s. From the origins of the word, you see the words ‘pagan’, ‘false god’, ‘statue’, so we can correctly infer that and idol is NOT a good thing that a Christian should be looking at or dealing with. The Lord has given strict instructions about idols as you can see in scripture here: Leviticus 26:1 - Ye shall make you no idols nor graven image, neither rear you up a standing image, neither shall ye set up any image of stone in your land, to bow down unto it: for I am the LORD your God. -

The Palmyrene Prosopography

THE PALMYRENE PROSOPOGRAPHY by Palmira Piersimoni University College London Thesis submitted for the Higher Degree of Doctor of Philosophy London 1995 C II. TRIBES, CLANS AND FAMILIES (i. t. II. TRIBES, CLANS AND FAMILIES The problem of the social structure at Palmyra has already been met by many authors who have focused their interest mainly to the study of the tribal organisation'. In dealing with this subject, it comes natural to attempt a distinction amongst the so-called tribes or family groups, for they are so well and widely attested. On the other hand, as shall be seen, it is not easy to define exactly what a tribe or a clan meant in terms of structure and size and which are the limits to take into account in trying to distinguish them. At the heart of Palmyrene social organisation we find not only individuals or families but tribes or groups of families, in any case groups linked by a common (true or presumed) ancestry. The Palmyrene language expresses the main gentilic grouping with phd2, for which the Greek corresponding word is ØuAi in the bilingual texts. The most common Palmyrene formula is: dynwpbd biiyx... 'who is from the tribe of', where sometimes the word phd is omitted. Usually, the term bny introduces the name of a tribe that either refers to a common ancestor or represents a guild as the Ben Komarê, lit. 'the Sons of the priest' and the Benê Zimrâ, 'the sons of the cantors' 3 , according to a well-established Semitic tradition of attaching the guilds' names to an ancestor, so that we have the corporations of pastoral nomads, musicians, smiths, etc. -

Bauhistorische Untersuchungen Am Almaqah-Heiligtum Von Sirwah Vom

BAUHISTORISCHE UNTERSUCHUNGEN AM ALMAQAH-HEILIGTUM VON SIRWAH VOM KULTPLATZ ZUM HEILIGTUM Von der Fakultät Architektur, Bauingenieurwesen und Stadtplanung der Brandenburgischen Technischen Universität Cottbus zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften (Dr.-Ing.) genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Dipl.-Ing. Nicole Röring geboren am 18.01.1972 in Lippstadt Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Adolf Hoffmann Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Klaus Rheidt Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Ernst-Ludwig Schwandner Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 06.10.2006 Band 1/Text In Erinnerung an meinen Vater Engelbert Röring Zusammenfassung Das Almaqah-Heiligtum von Sirwah befindet sich auf der südarabischen Halbinsel im Nordjemen etwa 80 km östlich der heutigen Hauptstadt Sanaa und ca. 40 km westlich von Marib, der einstigen Hauptstadt des Königreichs von Saba. Das Heiligtum, dessen Blütezeit auf das 7. Jh. v. Chr. zurückgeht, war dem sabäischen Reichsgott Almaqah geweiht. Das Heiligtum wird von einer bis zu 10 m hoch anstehenden und etwa 90 m langen, gekurvten Umfassungsmauer eingefasst. Im Nordwesten der Anlage sind zwei Propyla vorgelagert, die die Haupterschließungsachse bilden. Quer zum Inneren Propylon erstreckt sich entlang der Westseite eine einst überdachte Terrasse mit unterschiedlichen Einbauten. Kern der Gesamtanlage bildet ein Innenhof, der von der Umfassungsmauer mit einem umlaufenden Wehrgang gerahmt wird. Den Innenhof prägen unterschiedliche Einbauten rechteckiger Kubatur sowie insbesondere das große Inschriftenmonument, des frühen sabäischen Herrschers, Mukarrib Karib`il Watar, das eins der wichtigsten historischen Quellen Südwestarabiens darstellt. Die bauforscherische Untersuchung des Almaqah-Heiligtums von Sirwah konnte eine sukzessive Entwicklung eines Kultplatzes zu einem ‘internationalen’ Sakralkomplex nachweisen, die die komplexe Chronologie der Baulichkeiten des Heiligtums und eine damit einhergehende mindestens 1000jährige Nutzungszeit mit insgesamt fünfzehn Entwicklungsphasen belegt, die sich wiederum in fünf große Bauphasen gliedern lassen.