Harmonisation of Arabic and Latin Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

Developing an Arabic Typography Course for Visual Communication Design

Developing an Arabic Typography course for Visual Communication Design Students in the Middle East and North African Region A thesis submitted to the School of Visual Communication Design, College of Communication and Information of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts by Basma Almusallam May, 2014 Thesis written by Basma Almusallam B.F.A, Kuwait University, 2008 M.F.A, Kent State University, 2014 Approved by ___________________________ Jillian Coorey, M.F.A., Advisor ___________________________ AnnMarie LeBlanc, M.F.A., Director, School of Visual Communication Design ___________________________ Stanley T. Wearden, Ph.D., Dean, College of Communication and Information Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………...... iii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………….. v PREFACE………………………………………………………………………………..... vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………. 1 The Current Issue………………………………………………….. 1 Core Objectives……………………………………………………. 3 II. THE HISTORY OF THE ARABIC WRITING SYSTEM, CALLIGRAPHY AND TYPOGRAPHY………………………………………....………….. 4 The Arabic Writing System……………………………………….. 4 Arabic Calligraphy………………………………………………… 5 The Undocumented Art of Arabic Calligraphy……………….…… 6 The Shift Towards Typography and the Digital Era………………. 7 The Pressing Issue of the Present………………………………….. 8 A NOTE ON THE PROCESS…………………………………………………………….. 10 Applying a Framework for Research Documentation…………….. 11 Mental Model……………………………………………………… 12 Proposed User Testing……………………………………………. -

Language Culture Type 2.Indd

Arabic script and typography is alphabetical; the direction of writing is from right to left; within a word, most letters form connected groups. AOne expects an alphabet to consist of a few dozen letters repre- senting one unique sound each. The Arabic alphabet evolved somewhat away from this ideal: although most letters correspond to a sound, a few letters are ambivalent between two or more sounds. Some letters don’t represent sound at all: they have only a grammatical function. For modern office use there are 28 basic letters, eight of them only differentiated from other letters by diacritics, and six optional letters for representing vowels. Older spellings made less use of diacritics for dif- ferentiating; on the other hand, to facilitate Qur’an recitation, additional vowel signs occur, along with elaborate cantillation marks. To acknowl- edge slight variations of the received text, some Qur’an editions have ad- ditional diacritics, discretely adding or eliminating consonant letters. As the Arabic script evolved into a connected script, it developed an elaborate system of assimilations and dissimilations between adjacent letters. Outside a small group of connoisseurs and calligraphers who study the principles established by the Ottoman letter artists, surpris- ingly little is understood of the efficiency and subtlety of this system,¹ and modern industrial type designs follow the approach found in el- ementary Western teaching materials.² There, beginners in Arabic script are given a maximally simplified scheme. While simplification is totally sound from a pedagogical perspective, it provides too narrow a basis for the development of professional typography. The Arabic script stems from the same source as the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew writing systems: Phoenician (figure 1).³ The underlying proto- alphabet had some two dozen characters; there were no vowels. -

Designing Software to Meet the Needs of International Users

DESIGNING SOFTWARE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL USERS A Project Report Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by David Mohr December 2013 © 2013 David Mohr ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY The Undersigned Graduate Committee Approves the Project Report Titled DESIGNING SOFTWARE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL USERS by David Mohr APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY _____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Chuck Darrah, Department of Anthropology Date _____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Roberto Gonzalez, Department of Anthropology Date _____________________________________________________________________________ Professor Awad Awad, Middle Eastern Studies, Department of Humanities, Date Arabic Coordinator, Department of World Languages and Literatures Abstract Most software applications are designed and built in North America, catering to English- speaking, North American users. Ethnography is commonly used to ensure the product addresses the needs of domestic customers, but there is no analogous research with regard to foreign consumers. As a result, often times the features in these applications fail to sufficiently address the needs, expectations, and workflow of non-English-speaking users. Although software engineering manuals minutely detail the technical aspects of bringing an English application to -

Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone

Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Table of Contents 1. General Information 2 1.1 Use of Latin Script characters in domain names 3 1.2 Target Script for the Proposed Generation Panel 4 1.2.1 Diacritics 5 1.3 Countries with significant user communities using Latin script 6 2. Proposed Initial Composition of the Panel and Relationship with Past Work or Working Groups 7 3. Work Plan 13 3.1 Suggested Timeline with Significant Milestones 13 3.2 Sources for funding travel and logistics 16 3.3 Need for ICANN provided advisors 17 4. References 17 1 Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information The Latin script1 or Roman script is a major writing system of the world today, and the most widely used in terms of number of languages and number of speakers, with circa 70% of the world’s readers and writers making use of this script2 (Wikipedia). Historically, it is derived from the Greek alphabet, as is the Cyrillic script. The Greek alphabet is in turn derived from the Phoenician alphabet which dates to the mid-11th century BC and is itself based on older scripts. This explains why Latin, Cyrillic and Greek share some letters, which may become relevant to the ruleset in the form of cross-script variants. The Latin alphabet itself originated in Italy in the 7th Century BC. The original alphabet contained 21 upper case only letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, Z, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V and X. -

Processing South Asian Languages Written in the Latin Script: the Dakshina Dataset

Processing South Asian Languages Written in the Latin Script: the Dakshina Dataset Brian Roarky, Lawrence Wolf-Sonkiny, Christo Kirovy, Sabrina J. Mielkez, Cibu Johnyy, Işın Demirşahiny and Keith Hally yGoogle Research zJohns Hopkins University {roark,wolfsonkin,ckirov,cibu,isin,kbhall}@google.com [email protected] Abstract This paper describes the Dakshina dataset, a new resource consisting of text in both the Latin and native scripts for 12 South Asian languages. The dataset includes, for each language: 1) native script Wikipedia text; 2) a romanization lexicon; and 3) full sentence parallel data in both a native script of the language and the basic Latin alphabet. We document the methods used for preparation and selection of the Wikipedia text in each language; collection of attested romanizations for sampled lexicons; and manual romanization of held-out sentences from the native script collections. We additionally provide baseline results on several tasks made possible by the dataset, including single word transliteration, full sentence transliteration, and language modeling of native script and romanized text. Keywords: romanization, transliteration, South Asian languages 1. Introduction lingua franca, the prevalence of loanwords and code switch- Languages in South Asia – a region covering India, Pak- ing (largely but not exclusively with English) is high. istan, Bangladesh and neighboring countries – are generally Unlike translations, human generated parallel versions of written with Brahmic or Perso-Arabic scripts, but are also text in the native scripts of these languages and romanized often written in the Latin script, most notably for informal versions do not spontaneously occur in any meaningful vol- communication such as within SMS messages, WhatsApp, ume. -

Characters for Classical Latin

Characters for Classical Latin David J. Perry version 13, 2 July 2020 Introduction The purpose of this document is to identify all characters of interest to those who work with Classical Latin, no matter how rare. Epigraphers will want many of these, but I want to collect any character that is needed in any context. Those that are already available in Unicode will be so identified; those that may be available can be debated; and those that are clearly absent and should be proposed can be proposed; and those that are so rare as to be unencodable will be known. If you have any suggestions for additional characters or reactions to the suggestions made here, please email me at [email protected] . No matter how rare, let’s get all possible characters on this list. Version 6 of this document has been updated to reflect the many characters of interest to Latinists encoded as of Unicode version 13.0. Characters are indicated by their Unicode value, a hexadecimal number, and their name printed IN SMALL CAPITALS. Unicode values may be preceded by U+ to set them off from surrounding text. Combining diacritics are printed over a dotted cir- cle ◌ to show that they are intended to be used over a base character. For more basic information about Unicode, see the website of The Unicode Consortium, http://www.unicode.org/ or my book cited below. Please note that abbreviations constructed with lines above or through existing let- ters are not considered separate characters except in unusual circumstances, nor are the space-saving ligatures found in Latin inscriptions unless they have a unique grammatical or phonemic function (which they normally don’t). -

Greek Type Design Introduction

A primer on Greek type design by Gerry Leonidas T the 1997 ATypI Conference at Reading I gave a talk Awith the title ‘Typography & the Greek language: designing typefaces in a cultural context.’ The inspiration for that talk was a discussion with Christopher Burke on designing typefaces for a script one is not linguistically familiar with. My position was that knowledge and use of a language is not a prerequisite for understanding the script to a very high, if not conclusive, degree. In other words, although a ‘typographically attuned’ native user should test a design in real circumstances, any designer could, with the right preparation and monitoring, produce competent typefaces. This position was based on my understanding of the decisions a designer must make in designing a Greek typeface. I should add that this argument had two weak points: one, it was based on a small amount of personal experience in type design and a lot of intuition, rather than research; and, two, it was quite possible that, as a Greek, I was making the ‘right’ choices by default. Since 1997, my own work proved me right on the first point, and that of other designers – both Greeks and non- Greeks – on the second. The last few years saw multilingual typography literally explode. An obvious arena was the broader European region: the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997 which, at the same time as bringing the European Union closer to integration on a number of fields, marked a heightening of awareness in cultural characteristics, down to an explicit statement of support for dialects and local script variations. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Encoding Diversity for All the World's Languages

Encoding Diversity for All the World’s Languages The Script Encoding Initiative (Universal Scripts Project) Michael Everson, Evertype Westport, Co. Mayo, Ireland Bamako, Mali • 6 May 2005 1. Current State of the Unicode Standard • Unicode 4.1 defines over 97,000 characters 1. Current State of the Unicode Standard: New Script Additions Unicode 4.1 (31 March 2005): For Unicode 5.0 (2006): Buginese N’Ko Coptic Balinese Glagolitic Phags-pa New Tai Lue Phoenician Nuskhuri (extends Georgian) Syloti Nagri Cuneiform Tifinagh Kharoshthi Old Persian Cuneiform 1. Current State of the Unicode Standard • Unicode 4.1 defines over 97,000 characters • Unicode covers over 50 scripts (many of which are used for languages with over 5 million speakers) 1. Current State of the Unicode Standard • Unicode 4.1 defines over 97,000 characters • Unicode covers over 50 scripts (often used for languages with over 5 million speakers) • Unicode enables millions of users worldwide to view web pages, send e-mails, converse in chat-rooms, and share text documents in their native script 1. Current State of the Unicode Standard • Unicode 4.1 defines over 97,000 characters • Unicode covers over 50 scripts (often used for languages with over 5 million speakers) • Unicode enables millions of users worldwide to view web pages, send e-mails, converse in chat- rooms, and share text documents in their native script • Unicode is widely supported by current fonts and operating systems, but… Over 80 scripts are missing! Missing Modern Minority Scripts India, Nepal, Southeast Asia China: -

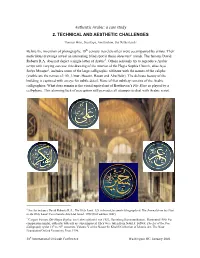

Authentic Arabic: a Case Study 2. TECHNICAL and AESTHETIC CHALLENGES

Authentic Arabic: a case study 2. TECHNICAL AND AESTHETIC CHALLENGES Thomas Milo, DecoType, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Before the invention of photography, 19th century travelers often were accompanied by artists. Their meticulous drawings reveal an interesting blind spot in these observers’ minds. The famous David Roberts R.A. does not depict a single letter of Arabic1. Others seriously try to reproduce Arabic script with varying success: this drawing of the interior of the Hagia Sophia Church, alias Aya Sofya Mosque2, includes some of the large calligraphic tableaux with the names of the caliphs (visible are the names of: Ali, Umar, Husain, Hasan and Abu Bakr). The delicate beauty of the building is captured with an eye for subtle detail. None of that subtlety remains of the Arabic calligraphies. What does remain is the visual equivalent of Beethoven’s Für Elise as played by a cell-phone. This alarming lack of perception still pervades all attempts to deal with Arabic script. 1 See for instance David Roberts R.A., The Holy Land, 123 coloured facsimile lithographs & The Journal from his Visit to the Holy Land, Terra Sancta Arts Ltd, Israel, 1982 (first edition 1842) 2 Caspare Fossati, Die Hagia Sophia, nach dem tafelwerk von 1852, Harenberg Kommunikation , Dortmund 1980. For comparison similar, authentic tableaux are superimposed. They were taken from Nabil F. Safwat, The Art of the Pen, Calligraphy of the 14th to 20th centuries, Volume V of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, The Nour Foundation/Oxford University Press 1996. 20th International Unicode Conference Washington DC, January 2002 Authentic Arabic 2 – Technical and Æsthetic Challenges A more recent illustration is a drawing of the interior of the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul3. -

Ancient and Other Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1.