Reading Runes in Late Medieval Manuscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monuments Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medieval England

Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 24 Kopár, Lilla, 2021: The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monu- ments. Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medi- eval England. In: Reading Runes. Proceedings of the Eighth International Sym posium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions, Nyköping, Sweden, 2–6 September 2014. Ed. by MacLeod, Mindy, Marco Bianchi and Henrik Williams. Uppsala. (Run rön 24.) Pp. 143–156. DOI: 10.33063/diva-438873 © 2021 Lilla Kopár (CC BY) LILLA KOPÁR The Rise and Fall of Anglo-Saxon Runic Stone Monuments Runic Inscriptions and the Development of Sculpture in Early Medieval England Abstract The Old English runic corpus contains at least thirty-seven inscriptions carved in stone, which are concentrated geographically in the north of England and dated mainly from the seventh to the ninth centuries. The quality and content of the inscriptions vary from simple names (or frag- ments thereof) to poetic vernacular memorial formulae. Nearly all of the inscriptions appear on monumental sculpture in an ecclesiastical context and are considered to have served commemor- ative purposes. Rune-inscribed stones show great variety in terms of monument type, from name-stones, cross-shafts and slabs to elaborate monumental crosses that served different func- tions and audiences. Their inscriptions have often been analyzed by runologists and epigraphers from a linguistic or epigraphic point of view, but the relationship of these inscribed monuments to other sculptured stones has received less attention in runological circles. Thus the present article explores the place and development of rune-inscribed monuments in the context of sculp- tural production in pre-Conquest England, and identifies periods of innovation and change in the creation and function of runic monuments. -

Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone

Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Table of Contents 1. General Information 2 1.1 Use of Latin Script characters in domain names 3 1.2 Target Script for the Proposed Generation Panel 4 1.2.1 Diacritics 5 1.3 Countries with significant user communities using Latin script 6 2. Proposed Initial Composition of the Panel and Relationship with Past Work or Working Groups 7 3. Work Plan 13 3.1 Suggested Timeline with Significant Milestones 13 3.2 Sources for funding travel and logistics 16 3.3 Need for ICANN provided advisors 17 4. References 17 1 Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information The Latin script1 or Roman script is a major writing system of the world today, and the most widely used in terms of number of languages and number of speakers, with circa 70% of the world’s readers and writers making use of this script2 (Wikipedia). Historically, it is derived from the Greek alphabet, as is the Cyrillic script. The Greek alphabet is in turn derived from the Phoenician alphabet which dates to the mid-11th century BC and is itself based on older scripts. This explains why Latin, Cyrillic and Greek share some letters, which may become relevant to the ruleset in the form of cross-script variants. The Latin alphabet itself originated in Italy in the 7th Century BC. The original alphabet contained 21 upper case only letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, Z, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V and X. -

Processing South Asian Languages Written in the Latin Script: the Dakshina Dataset

Processing South Asian Languages Written in the Latin Script: the Dakshina Dataset Brian Roarky, Lawrence Wolf-Sonkiny, Christo Kirovy, Sabrina J. Mielkez, Cibu Johnyy, Işın Demirşahiny and Keith Hally yGoogle Research zJohns Hopkins University {roark,wolfsonkin,ckirov,cibu,isin,kbhall}@google.com [email protected] Abstract This paper describes the Dakshina dataset, a new resource consisting of text in both the Latin and native scripts for 12 South Asian languages. The dataset includes, for each language: 1) native script Wikipedia text; 2) a romanization lexicon; and 3) full sentence parallel data in both a native script of the language and the basic Latin alphabet. We document the methods used for preparation and selection of the Wikipedia text in each language; collection of attested romanizations for sampled lexicons; and manual romanization of held-out sentences from the native script collections. We additionally provide baseline results on several tasks made possible by the dataset, including single word transliteration, full sentence transliteration, and language modeling of native script and romanized text. Keywords: romanization, transliteration, South Asian languages 1. Introduction lingua franca, the prevalence of loanwords and code switch- Languages in South Asia – a region covering India, Pak- ing (largely but not exclusively with English) is high. istan, Bangladesh and neighboring countries – are generally Unlike translations, human generated parallel versions of written with Brahmic or Perso-Arabic scripts, but are also text in the native scripts of these languages and romanized often written in the Latin script, most notably for informal versions do not spontaneously occur in any meaningful vol- communication such as within SMS messages, WhatsApp, ume. -

Characters for Classical Latin

Characters for Classical Latin David J. Perry version 13, 2 July 2020 Introduction The purpose of this document is to identify all characters of interest to those who work with Classical Latin, no matter how rare. Epigraphers will want many of these, but I want to collect any character that is needed in any context. Those that are already available in Unicode will be so identified; those that may be available can be debated; and those that are clearly absent and should be proposed can be proposed; and those that are so rare as to be unencodable will be known. If you have any suggestions for additional characters or reactions to the suggestions made here, please email me at [email protected] . No matter how rare, let’s get all possible characters on this list. Version 6 of this document has been updated to reflect the many characters of interest to Latinists encoded as of Unicode version 13.0. Characters are indicated by their Unicode value, a hexadecimal number, and their name printed IN SMALL CAPITALS. Unicode values may be preceded by U+ to set them off from surrounding text. Combining diacritics are printed over a dotted cir- cle ◌ to show that they are intended to be used over a base character. For more basic information about Unicode, see the website of The Unicode Consortium, http://www.unicode.org/ or my book cited below. Please note that abbreviations constructed with lines above or through existing let- ters are not considered separate characters except in unusual circumstances, nor are the space-saving ligatures found in Latin inscriptions unless they have a unique grammatical or phonemic function (which they normally don’t). -

Myths of the Rune Stone: Viking Martyrs and the Birthplace of America

book review Myths of the Rune Stone: Viking Martyrs For example, Krueger’s and the Birthplace of America take on the local and reli- David M. Krueger gious dimensions of the (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015, 214 p., stone’s history is original. Paper, $24.95.) He excellently explores how the stone became a near- Many places claim to be the birthplace of America, but few sacred artifact even outside have been as contested as the one near Kensington, Minnesota. the Scandinavian American The source of this claim, a stone slab unearthed in 1898, is the ethnic community. Krueger subject of David Krueger’s Myths of the Rune Stone. This first shows how in the 1920s the comprehensive book about the popular meaning of the Kens- stone— by way of a failed ington Rune Stone is a welcome contribution to the study of its plan for a massive 200- foot historiography and to the impact of local culture on an Ameri- monument— became a can origin myth. tool of small- town booster- Since its discovery by a Swedish- born farmer, the Kensing- ism. In 1928, the stone was ton Rune Stone’s claim that Norsemen were present in what purchased by a group of is now Minnesota in the year 1362 has been a topic of heated Alexandria businessmen controversy. Although scholars of Scandinavian languages and and put on display in a downtown bank. To the Alexandria runology (the study of runic inscriptions) have long agreed community, the stone was a source of prestige and a strategy about its nineteenth- century origin, the stone has continued to to promote tourism. -

Greek Type Design Introduction

A primer on Greek type design by Gerry Leonidas T the 1997 ATypI Conference at Reading I gave a talk Awith the title ‘Typography & the Greek language: designing typefaces in a cultural context.’ The inspiration for that talk was a discussion with Christopher Burke on designing typefaces for a script one is not linguistically familiar with. My position was that knowledge and use of a language is not a prerequisite for understanding the script to a very high, if not conclusive, degree. In other words, although a ‘typographically attuned’ native user should test a design in real circumstances, any designer could, with the right preparation and monitoring, produce competent typefaces. This position was based on my understanding of the decisions a designer must make in designing a Greek typeface. I should add that this argument had two weak points: one, it was based on a small amount of personal experience in type design and a lot of intuition, rather than research; and, two, it was quite possible that, as a Greek, I was making the ‘right’ choices by default. Since 1997, my own work proved me right on the first point, and that of other designers – both Greeks and non- Greeks – on the second. The last few years saw multilingual typography literally explode. An obvious arena was the broader European region: the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997 which, at the same time as bringing the European Union closer to integration on a number of fields, marked a heightening of awareness in cultural characteristics, down to an explicit statement of support for dialects and local script variations. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

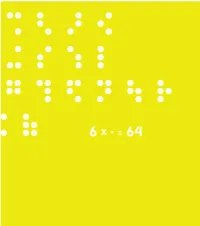

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Anglo-Saxon Runes

Runes Each rune can mean something in divination (fortune telling) but they also act as a phonetic alphabet. This means that they can sound out words. When writing your name or whatever in runes, don’t pay attention to the letters we use, but rather the sounds we use to make up the words. Then finds the runes with the closest sounds and put them together. Anglo- Swedo- Roman Germanic Danish Saxon Norwegian A ansuz ac ar or god oak-tree (?) AE aesch ash-tree A/O or B berkanan bercon or birch-twig (?) C cen torch D dagaz day E ehwaz horse EA ear earth, grave(?) F fehu feoh fe fe money, cattle, money, money, money, wealth property property property gyfu / G gebo geofu gift gift (?) G gar spear H hagalaz hail hagol (?) I isa is iss ice ice ice Ï The sound of this character was something ihwaz / close to, but not exactly eihwaz like I or IE. yew-tree J jera year, fruitful part of the year K kenaz calc torch, flame (?) (?) K name unknown L laguz / laukaz water / fertility M mannaz man N naudiz need, necessity, nou (?) extremity ing NG ingwaz the god the god "Ing" "Ing" O othala- hereditary land, oethil possession OE P perth-(?) peorth meaning unclear (?) R raidho reth (?) riding, carriage S sowilo sun or sol (?) or sun tiwaz / teiwaz T the god Tiw (whose name survives in Tyr "Tuesday") TH thurisaz thorn thurs giant, monster (?) thorn giant, monster U uruz ur wild ox (?) wild ox W wunjo joy X Y yr bow (?) Z agiz(?) meaning unclear Now write your name: _________________________________________________________________ Rune table borrowed from: www.cratchit.org/dleigh/alpha/runes/runes.htm . -

Runestone Images and Visual Communication

RUNESTONE IMAGES AND VISUAL COMMUNICATION IN VIKING AGE SCANDINAVIA MARJOLEIN STERN, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JULY 2013 Abstract The aim of this thesis is the visual analysis of the corpus of Viking Age Scandinavian memorial stones that are decorated with figural images. The thesis presents an overview of the different kinds of images and their interpretations. The analysis of the visual relationships between the images, ornamentation, crosses, and runic inscriptions identifies some tendencies in the visual hierarchy between these different design elements. The contents of the inscriptions on runestones with images are also analysed in relation to the type of image and compared to runestone inscriptions in general. The main outcome of this analysis is that there is a correlation between the occurrence of optional elements in the inscription and figural images in the decoration, but that only rarely is a particular type of image connected to specific inscription elements. In this thesis the carved memorial stones are considered as multimodal media in a communicative context. As such, visual communication theories and parallels in commemoration practices (especially burial customs and commemorative praise poetry) are employed in the second part of the thesis to reconstruct the cognitive and social contexts of the images on the monuments and how they create and display identities in the Viking Age visual communication. Acknowledgements Many people have supported and inspired me throughout my PhD. I am very grateful to my supervisors Judith Jesch and Christina Lee, who have been incredibly generous with their time, advice, and bananas. -

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

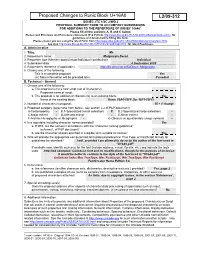

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4. -

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters Version 2.06, October 31, 2014 Pim Rietbroek Preamble Few typefaces – if any – allow the user to access every Latin character, every IPA character, every diacritic, and to have these combine in a typographically satisfactory manner, in a range of styles (roman, italic, and more); even fewer add full support for Greek, both modern and ancient, with specialised characters that papyrologists and epigraphers need; not to mention coverage of the Slavic languages in the Cyrillic range. The Brill typeface aims to do just that, and to be a tool for all scholars in the humanities; for Brill’s authors and editors; for Brill’s staff and service providers; and finally, for anyone in need of this tool, as long as it is not used for any commercial gain.* There are several fonts in different styles, each of which has the same set of characters as all the others. The Unicode Standard is rigorously adhered to: there is no dependence on the Private Use Area (PUA), as it happens frequently in other fonts with regard to characters carrying rare diacritics or combinations of diacritics. Instead, all alphabetic characters can carry any diacritic or combination of diacritics, even stacked, with automatic correct positioning. This is made possible by the inclusion of all of Unicode’s combining characters and by the application of extensive OpenType Glyph Positioning programming. Credits The Brill fonts are an original design by John Hudson of Tiro Typeworks. Alice Savoie contributed to Brill bold and bold italic. The black-letter (‘Fraktur’) range of characters was made by Karsten Lücke.